Imagine, for a second, that Kanye West is not the touchstone pop star of a generation, or the most critically acclaimed rapper in history, or a lightning rod with an incredible ability to create historic news events out of thin air, but is instead, basically, DJ Khaled. So roughly as omnipresent and annoying, yes, but also someone who is not a rapper, exactly, or a producer, really, but is instead a music industry figure who convinces dozens of other artists that it’s in their best interest to create and release rap songs under his name.

If you wanted to study the cult of genius, you could do worse than starting here. DJ Khaled is a hitmaker and some version of royalty (Beyoncé and Jay Z use him as a status symbol), but also a joke—a court jester for an America being strangled to death by capitalism whose actual role in the creation of his nominal art, if you were to quiz even actual fans of his music, would be unknown and perhaps even dismissed. West, meanwhile, is his inverse: the most serious of artists, who despite being enriched by capitalism also positions himself as its victim at every turn, and whose actual role in the creation of his nominal art is lionized and canonized, especially by his fans. This is true even as his universe of collaborators expands wildly with every successive album, forming constellations of artists spanning genres and disciplines and classes who leave fingerprint smudges on his work to be dusted and examined under magnifying glasses by very many willing (though not always able) sleuths.

On ye, that constellation revolves around what appears to be just a few friends. (The credits released so far are bare bones, leading to wild guesses about whose voices and beats we’re actually listening to.) A main player is Francis Starlite of Francis & the Lights, who has worked his way into West’s inner circle over the years. (He composed the current theme song for Keeping Up With the Kardashians.) His glassy electro-pop—which has the effect of breath fogging up a window—provides the background for several of the album’s tracks, leading ye with a gentle touch it might otherwise lack. Starlite is also a frequent collaborator of West successor Chance the Rapper, who doesn’t appear here but whose own brand of digitized, homespun gospel seems to be the album’s source of warmth.

This would be the starting point, I think, for finding any sort of redeeming value in West’s almost completely useless new album, ye. Following a modus operandi that began with his sprawling and spiraling 2010 epic My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, he has seemingly stitched together a body of work from the contributions of others that nonetheless sounds like nobody else but Kanye West. The problem, which coursed through his last album The Life of Pablo but is parasitic here, is the presence of himself at the center of it all—unrepentantly sour and hopelessly misguided, rapping about both universal issues and those entirely of his own creation with the insight of a thumbtack. If this was a DJ Khaled album, which is to say one where its creator is essentially absent, it might actually be kind of good.

Also Read

GEAR THAT MADE THE GAME: Rap Machinery

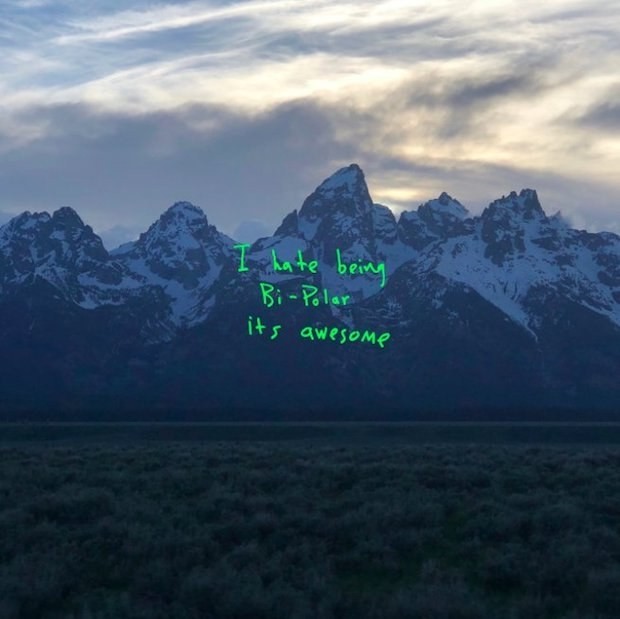

What we have instead is the most insular and impenetrable album from a man whose art has always gloriously been dedicated to the self. ye, as its cover makes clear, is his most bracingly personal album, a documentation of his increasingly public wrestling with his mental health and corroded life. (It’s also a nearly instant one at that—West claims he scrapped an entire album to record ye in the last month.) He has also never felt more distant; locked away in self-created prisons in Calabasas and Wyoming, the rapper whose relatability made him a cross-demographic superstar now has problems and solutions that are almost completely unrecognizable to the common man.

This has been coming, but gradually. Yeezus, a beautiful and ugly masterpiece of acidity, was at times unmoored from any general notion of reality. There, West spoke of the crush of racism, but within the clandestine world of high fashion that accommodated his whims and elevated his celebrity. He rapped about his sexual fantasies, twisted and violent, but left the implications unexamined. If you wanted to be turned off by Kanye West there was ample material on Yeezus, but it also had an undeniable, transferable energy, a crackling and palpable electricity. The Life of Pablo shared some of Yeezus’ worst traits and very few, if any, of its best ones, but it had some songs and moments that helped give it the shape and appeal of a proper album, even as he droned on about internecine personal feuds and troubles that afflict only the rich.

ye has nothing of the sort. A friendly framing of the album by NPR’s Rodney Carmichael holds that it represents West “trying to bring us into his bubble” or hoping to “transmit an SOS signal from deep within” it. Either of those things might be true, but on both fronts he has failed. If he was trying to poke a hole in the bubble he lives in, he has only made it clear that said bubble is not viscous like soap and water but hard like glass. There is nothing new to be learned from this album burdened by crudely formed raps about his already exhaustively covered life and deeply muddled politics. When he imagines the consequences of being “#MeToo’d,” the most he can come up with is that he’ll end up on “E! News.” The last several months of West’s existence, meanwhile, have indeed been a ringing SOS signal; ye makes a strong argument that we have little use for an album version of it.

The most generous reading of ye is that West wants us to witness his public breakdown and the slow-motion implosion of his reputation. The album would then theoretically be a unique document of what happens at the intersection of mental health and celebrity. He would, maybe, accomplish his mission of asking the public to examine their expectations of artists. But in order for us to watch the spectacle of his life going up in flames, and to think about what has caused it and why, and to extend our empathy to him as a victim, we have to descend to the depths of West’s subterranean nihilism—to live where he lives. Alas, ye is in no way fascinating enough for that journey to be justified.

Still, the music at times almost makes it worth it. The beginning of “I Thought About Killing You” smears West’s own vocoderized harmonies over a loop of Francis Starlite weeping the phrase “I know,” the empathy West seems to crave dripping down its sides. If he never said a word on the song it might actually be poignant. The sunlit “Wouldn’t Leave” feels like the moment when rays begins to peek through the storm clouds, except it’s a celebration of men abusing the love and compassion extended to them by their wives. Ty Dolla $ign and Jeremih do sound great, though! “Violent Crimes,” handled largely by the recent G.O.O.D. Music signee 070 Shake, might be an affecting, dewy ballad if West wasn’t rapping very weirdly and possessively about his daughter’s body. The song, and album, ends with what appears to be a clip of a voicemail left for Kanye by Nicki Minaj; it sounds like the moment on any number of rap albums where someone calls in from prison. This feels appropriate.

“Violent Crimes” might also be the album’s most instructive track, in that with the right software you could very easily remove West’s part and have a perfectly fine song. ye, 24 minutes long and barely structured, makes it easy to picture a Kanye album with no Kanye, one where his skill and appetite for curation leads to something akin to a museum exhibit, with artists intersecting under the guiding thematic hand of an influential and revered auteur. (Pusha T’s Daytona gets us close.) Of course, this is the person West wants us to see; DJ Khaled, to pick just one contemporary, is afforded no such fantasy. Kanye used to justify such flights of imagination, his albums obsessively dissected, ranked, and considered in the grand pantheon of human artistic achievement. ye makes expending that sort of mental energy seem incredibly silly. Let us never speak of it again.