“We’re an underground cult band,” says Third Eye Blind frontman Stephan Jenkins. “We’ve been camouflaged by hit songs.”

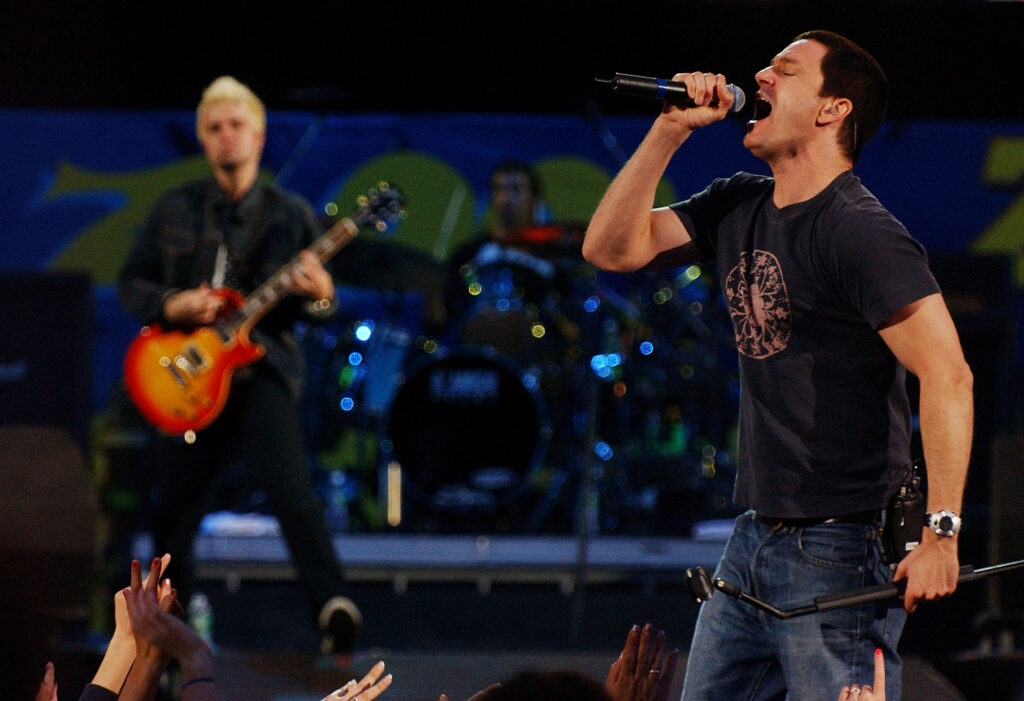

It’s late March, and he’s just finished soundcheck at Pennsylvania’s regal Hershey Theater. The quintet warmed up with everything from deep cuts (Ursa Major’s “Monotov’s Private Opera,” outtake “Second Born”) to singles (including “Box of Bones,” from 2021’s Our Bande Apart), with attentive VIP fans watching.

“I don’t like ‘90s kick drums. I want a ‘70s kick drum,” Jenkins says mid-practice to crew members, making thud sounds into the mic. He bounces off the stage to chat, but before we begin, he walks back towards the front-of-house engineer, located underneath the hanging mezzanine.

“It’s a beautiful room,” he says of the 1,900-seat venue, as we walk down the aisle for our interview. “We’ve never played here before, but I guess we’ll see how it sounds.”

Jenkins, famously charismatic, plays the part of the nonchalant rock star well. But you don’t survive three decades in such a volatile industry, from the heights of commercial success through this so-called “cult” era, by being blasé. The songwriter co-founded the band in 1993 and remains the lone original member. (Longtime drummer Brad Hargreaves joined in 1995.) Through it all, Jenkins has been Third Eye Blind’s driving force.

With their first two LPs, 1997’s multi-platinum Third Eye Blind and 1999 follow-up Blue, the San Francisco alt-rockers ascended to superstardom. Armed with a collection of enormous hits including “Semi-Charmed Life,” a sunkissed account of hard drugs and casual sex; “Jumper,” an anti-suicide anthem with shades of allyship; and “Never Let You Go,” a power-pop ode to “stupid things” and “mood rings,” the band went from tiny clubs to stadiums in less than a year’s time.

“It went so quickly from ‘nobody knows your name’ to headlining stadiums,” Jenkins says of the band’s meteoric rise. “We played SNL. We didn’t have any clothes. We were in so many ways not prepared. I was not psychologically prepared.”

No one could have reasonably expected the next album, Out of the Vein, to reach the commercial heights of their self-titled debut, yet no one could have expected what came next either. Around the time of its release (May 13, 2003), the band’s record label, Elektra, was being absorbed into fellow Warner subsidiary Atlantic Records: “[Current CEO] Craig Kallman was the guy, and I don’t think he had any interest in us whatsoever,” says Jenkins. “But they gave us money.”

Turbulence was nothing new for the songwriter, then 38. (Leading up to 1997’s self-titled, he was doing everything he could to make ends meet, like “sleeping in cleaning closets” or “on packing foam,” urban legends that he insists are true.) But Out of the Vein marked “a period of really, really big, tumultuous” change.

“We had changed band members, but also crew members,” he shares. “We were riddled with toxic relationships that we were trying to get past.”

They haven’t been without drama over the years. Several lawsuits between feuding band members have spilled out in the public periphery. Perhaps it’s just par for course when you hit it as big as Third Eye Blind did, when they did.

Nonetheless, when asked about the addition of guitarist Tony Fredianelli for Out of the Vein, he lauds all the band’s previous and current members, and the “different things they bring” to the table. In particular, Fredianelli, and the guitarist he replaced, Kevin Cadogan, employed abstract open tunings on Third Eye Blind records that, whether listeners realize it or not, became a hallmark of their sound from 1997’s self-titled through 2009’s Ursa Major.

“I’m very much about landscape,” says Jenkins, who has also produced (or co-produced) the band since the very beginning. “Trying to make a musical landscape, and reflecting on the internal landscape… You just can’t really do that in standard tuning. You kinda wanna open up the space.”

So that was Out of the Vein’s constant — but for Jenkins, everything else was in motion.

“I’d gone through a really big breakup. It was a very public relationship, even though we made an effort for it to not be,” he says of his three years spent with actress Charlize Theron, which informed much of the album. “It’s not something I was used to. It’s an age-old thing in Hollywood… some people date people because there is career value in it. That’s just not where we were at, at all.

“Out of the Vein is my breakup album,” he says matter-of-factly. “Most of these songs were about the wrangling of this post-relationship with Charlize.”

Both of the album’s singles deal with that strife. In what may be one of the most poetic radio rock songs of the aughts, the novelly titled “Crystal Baller,” Jenkins is “Homesick for … primal knowing.” In “Blinded,” an equally monstrous opus that pays homage to both Icarus and cunnilingus, protagonist Jenkins finds himself relegated to “Just an old friend, coming over now to visit.”

Of “Blinded,” he says, “I needed a second crack at that one. I think I over-thought it,” plugging the band’s 2022 Unplugged album, which features three acoustic reworks from Out of the Vein. “I like it better on the unplugged record. I think it’s more proper.”

As for singles, that was it — only two. By comparison, Third Eye Blind and Blue had five and four, respectively. The promotional cycle for Out of the Vein, perhaps due in part to label instability, was disappointingly hollow: Jenkins recalls relatively little press surrounding its release and says the band didn’t choose either of their singles played on radio. (Stations, he says, played them at their own discretion.)

But of the breakup contingent, none tell a story as miraculous as “My Hit And Run.” The track, which may have been initially overshadowed by its curiously similar arrangement to Blue’s rapturous “Wounded,” tells an incredible true story where Jenkins is sent flying through the air toward certain death, seeing Theron right before impact. (“In the red lights and cathedrals, there’s a sign,” he sings on the chorus. “Don’t we always wish we had more time?”)

“It was night time. I was on my motorcycle, on my way to see Coldplay at this little club in San Francisco called Bimbo’s. I think they were debuting ‘The Scientist.’ I was going to hang out with them,” he recalls. “I was riding through an intersection, and next to me was this cathedral. A car makes an illegal turn right into me, and I’m sent flying through the air. I almost died.”

“I rolled up [from the wreck], and was like ‘fuck it.’ I’m still going to the show,” he continues with a laugh. As a singer that prides himself on how few gigs his band has canceled over the years, he seems pretty proud of making it to this one as well.

But not every song on the album was explicitly about Theron. Opener ”Faster,” which Jenkins says is about “longing,” spurred quite a bit of internal discourse from the frontman. “‘Faster’ really fits in with this record because at that time I was feeling judged and misunderstood,” he says. “Maybe by critics — I don’t even know what it was. I felt like I needed to go into protection mode.

“But it also had this real yearning like… ‘I’m not done… I’m not tired.’ ‘Faster’ was about this desire for life to hit you, but also knowing you gotta duck – like in defense… go into the cave or something. That yearning is still there – the yearning to go faster – to ‘get off one time and not apologize,’” he says, as the wheels visibly turn behind his eyes.

“I think consciously, I’m reliving it now — ‘cause look, when I write songs, I don’t know what they’re about,” he adds. “They’re not essays. They’re not intellectual. But they are about self-discovery, self-invention, and self-revelation. My friend Billy [Corgan, of the Smashing Pumpkins] was talking about this. When things are going great, there’s like a mystic element where you’re just downloading it. But you’re downloading it from your own psyche. You just don’t know exactly what it’s about. I realize now looking back at ‘Faster’: ‘I wanna get off one time.’ I wanna huck myself out there without self-consciousness, knowing this self-conscious mindset was creeping over me.”

Jenkins muses for a solid three minutes as if he wrote the song just hours prior. “That is not an artistic, creative, punk rock mindset,” he adds, laughing.

“I’m not for sale,” Jenkins says, when asked about the song’s final lyrics, which sweep it up and away into “Blinded.” “I’m not gonna play for the gallery. My convictions — I’m not gonna go and try to write this song you want me to write.”

That attitude seems to define his career. Many may see a band with so many big early hits as incapacitated in some ways – chained to the horse they rode in on, with nostalgia wagered upon it. But there’s also an artistic freedom that comes with it.

“We’ve been in uninterrupted radio play on KROQ for 26 years,” Jenkins says of the band’s enduring success. “It doesn’t matter what song I write. It’s not gonna go on radio because there’s not enough room. They’re only going to play so many.”

Considering the songs that are mainstays on terrestrial radio, it’s probably fair to say that fate was nearly sealed by the time Out of the Vein was released. That only added to the “end of motion” and ensuing longing Jenkins previously described. Out of the Vein was Third Eye Blind’s first true venture out of the vein.

“It’s Samuel Johnson,” he says of the album’s title. “He was an 18th-century London author and essayist who said, ‘Sometimes when I’m stuck to write, I just open a vein and let it bleed,’ meaning like – don’t judge yourself. Don’t mess with your purity. Let it come straight out of the vein.

“But also, I felt like I was now out of the vein,” he continues, describing the era. “I had been in this mode for a long time and had been jarred out of it. That’s why it’s like a breakup album… The gold is in a vein. You’re now out of the vein. You’re no longer in the gold state — you’re somewhere. It was that kind of sensation.”

The album’s cover bleeds with emotion as well. “It was this little boy from 1970, air-guitaring. He’d made himself a guitar,” Jenkins says of the photograph, Dude ’72, a work of the late Mick Rock. (He also notes that it was originally slated to be the cover of Mott The Hoople’s All The Young Dudes.) “To me that embodied the purity of spirit that one wants to hold onto… There’s me as a 13-year-old boy singing and playing drums. It’s just out there without any self-reflexiveness.

“And I think about that today,” he continues, bringing it back to the present. “That mindset can be cultivated, and that is my purpose every night. There will be points [during shows] where my body is just relaxed… more so now than… maybe ever.”

In self-deprecating fashion, he shares the reason the band is even touring at all at the moment: “We were supposed to have a new album out, but I fucked up and didn’t finish the lyrics.” He laughs, knowing very well it’s the same reason Out of the Vein was also delayed.

Though it’s often overshadowed by their first two records, which often receive preferential treatment in their setlists, it’s evident Jenkins is also immensely proud of their third album. In 2016, during an otherwise pedestrian interview with Reddit, he even went as far as to call Out of the Vein the most underrated album of all time.

When asked if he really believes that, he smirks. “Well, it was an album that was totally unpromoted,” he says. “I don’t know if I even believed it at the time, but it was something funny to say.”

Then he leans into a bit of signature swagger: “You’re not allowed to hype yourself up as an indie rock artist. But fuck that, I can put some bling on it once in a while.”