Before shiny, luxury high-rise condos began sprouting up—Whole Foods setting up shop, corporate drugstore chains taking over local storefronts, and VICE Media Group buying out buildings that housed beloved venues—a burgeoning underground music and arts scene thrived in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Driven by a like-minded alliance of freethinking creatives operating out of raw nooks and crannies, decrepit warehouses, unlicensed bars, and outlaw music spaces, this adventurous scene wasn’t just relegated to a single art form—it was an all-embracing and communal force of nature.

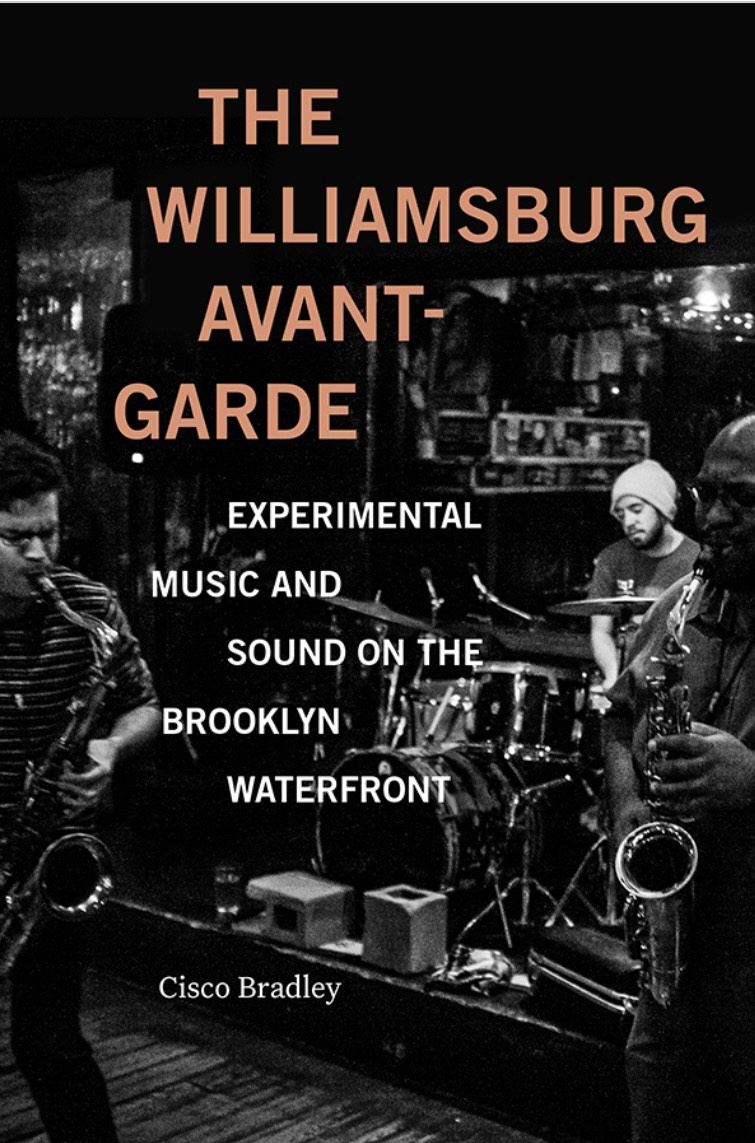

In his new book (released in February), writer and professor Cisco Bradley documents the ascent and rapid-fire crash of this musical movement that was in full-swing from the late ‘80s until 2014. Approaching the material with both a professorial and an up-close-and-personal touch, Bradley personally witnessed some of the scene’s mutating cultural and social shifts and the economics and gentrification that forced many of the venues Bradley writes about to shut down.

What’s revelatory about The Williamsburg Avant-Garde is Bradley’s telling of the across-the-musical-spectrum musicians who played a central role in spearheading the scene—and those who have continued to survive and thrive in the face of the ever-changing landscape. From MacArthur Foundation “Genius” grant recipient Mary Halvorson, “brutal-prog” pioneer Weasel Walter, avant-metal guitarists Mick Barr and Brandon Seabrook, saxophonist Matana Roberts, doom clarinetist Jeremiah Cymerman, and pianist Connie Crothers to punk-jazz outfit Little Women, Bradley goes deep into the wide-ranging music-makers who helped pave the way.

SPIN caught up with Bradley to talk about The Williamsburg Avant-Garde, the past, present and future of the underground, who’s carrying the torch, and how we arrived at this moment in time.

It was only two years ago that your book, Universal Tonality: The Life and Music of William Parker, was released. Parker has roots in the downtown NYC loft-jazz scene of the ‘70s. How do you see his path linked to the DIY warehouses, raw spaces that you detail in The Williamsburg Avant-Garde?

Art of any value or vision that is created in the U.S. is by necessity in DIY settings for the most part, due to inadequate grassroots arts funding. William Parker and his collaborators in the 1970s broke ground in the jazz lofts by holding steady to their artistic visions, while also committing to autonomy and self-determination as artists and human beings. Universal Tonality charts that history. In many ways things got worse with broader defunding of the arts under the Reagan administration in the 1980s, so The Williamsburg Avant-Garde is a study of the fallout of those policies, the divestment in our culture that has occurred, and how this has deeply devalued cultural production—that is, the entire process of creating new ideas, new cultural outcomes like music and visual art. We live in the distorted fantasy that consumer culture will somehow propel new, bold art to be made. It’s rarely the case. So much of America lives on recycled culture or mass-marketed lowest-common-denominator culture as a result. This is not a society in its natural state, it is one that has been starved of its ability to create, but still these intrepid artists have done just that, sacrificing a great deal, to offer us their futuristic visions.

Many of the performance spaces you cover in The Williamsburg Avant-Garde are long gone. Is there an existing support system in New York City for musicians?

Actually, I don’t think any of the venues I talk about in the book have survived. Not one. I wouldn’t say that there’s ever been a legit support system—there has only ever been what artists built for themselves. New York City was an unparalleled cultural center from the 1960s to the 1990s, primarily because parts of the city were broken—post-industrial areas, decaying residential zones—where artists could afford to live, and there were spaces for them to take over and turn into places of creation. Since the 1990s there have been several important developments. Commercial venues have been in decline, so non-profit institutions have moved in to fill the gap. They sustain the scene to a degree and contribute tremendously. But I’d say the other trend since the 1990s has been that working-class artists have left the city. Few artists can survive here now without family support.

Can you pinpoint a specific event or turning point where everything came crashing down in 2014? Some claim “the beginning of the end” was when VICE bought the building that housed the beloved music/community space Death by Audio.

I’d say there were three major turning points. The Rent Regulation Reform Act of 1997 weakened rent control laws and resulted in the immediate rise of rents across the city. The rezoning of much of Williamsburg from industrial to residential by the Bloomberg administration in 2005 was the most devastating and led to redevelopment throughout the neighborhood—the corporate takeover of most art spaces—and the mass eviction of artists living in lofts. Because some places were on five- or 10-year leases, the effect was at times delayed. But, as you say, the nail in the coffin was VICE’s purchase of the building that held Death by Audio and Glasslands. Though they claim to represent an interest in alternative culture, their move took out the last remaining organic cultural spaces in Williamsburg.

Was there a significant moment when the creative music community began developing their own movement in Brooklyn? You mention that 9/11 was a turning point.

I’d say it was its own movement from 1988 onwards, but as a community it reached its greatest critical mass in the period from 1998 to 2005. People were still building and expanding then. 9/11 sparked the gentrification of Brooklyn by forcing people out of Manhattan, but it took some years to manifest. After 2005 it was like trench warfare for artists trying to hold onto their living spaces, performance spaces, or moving south into other parts of the borough or, ultimately, to New Jersey, the Hudson Valley, New Haven, and so forth, where they can actually afford to live.

In the book, you talk about how it was an all-embracing scene where musicians of different genres and sounds shared bills.

I think these eclectic bills were the result of the high concentration of artists in a relatively small part of the city and the diverse range of their interests. The lofts and DIY venues were aimed at representing a community rather than a genre. We’ve definitely moved away from that in the past 15 years. The community is more segmented now, and I think this has hurt both the ability to build an audience as well as having potentially slowed down some of the artistic development itself. And communities now seem to often emerge from conservatories and music schools and remain cohesive for years. It’s a different kind of social atmosphere than it was 20 years ago.

You devote an entire chapter to the long-defunct live music venue Zebulon. Can you talk about how crucial it was to the Williamsburg scene?

If we look at the whole history of Williamsburg as a center for experimental music, Zebulon is clearly the most impactful venue. It was a rarity. It was actually legal, unlike most of the art spaces I cover, and the owners had an ear to the music scene. They had an interest in aesthetics and didn’t look at it purely as a money-making scheme. And they brought in established artists in the early years while soon giving way to younger artists. Providing a stage for young musicians is the most important thing any scene can do if any arts community is to survive.

Will there ever be a scene like this again in New York City?

NYC is losing its position as a music and art center, and if the trends continue, at some point we may be referring to NYC as a post-cultural space, a label that could already be applied for much of Manhattan and north Brooklyn. Also, since this is driven by economics, we must also admit that working-class perspectives in art have already been eradicated in NYC, more or less.

Musicians need more grassroots funding. Funds like the MacArthur are good for a few people, but to sustain a community we need an entirely different model.