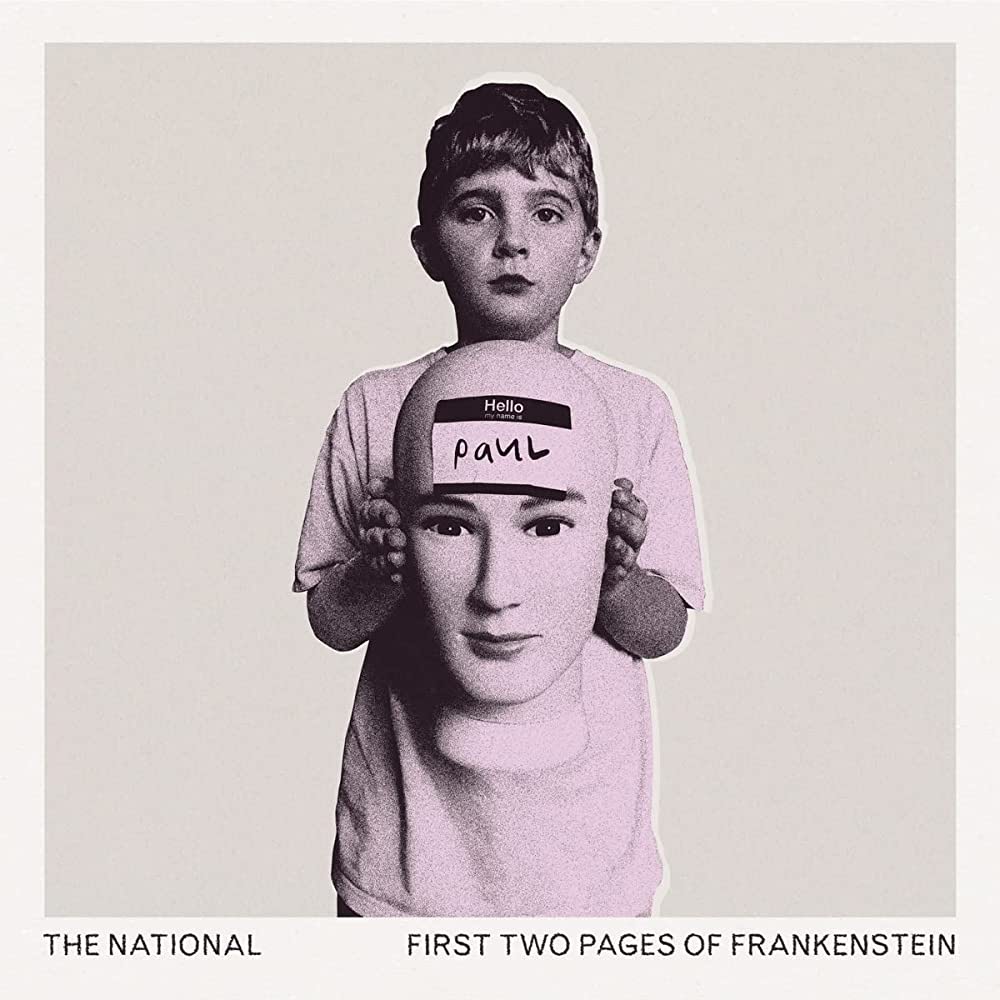

During the first few moments of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, one of the great literary masterpieces of the 19th Century, Shelley paints a strikingly downcast portrait of the character Beaufort. She describes his debilitating grief, which “only became more deep and rankling, when he had leisure for reflection; and at length it took so fast hold of his mind, that at the end of three months he lay on a bed of sickness, incapable of any exertion.” Funnily enough, the first two pages of this novel coaxed Matt Berninger out of a severe state of writer’s block.

A brief lull in creativity is only natural, but Berninger, the group’s frontman, wasn’t certain how long the period would last. Once he arbitrarily cracked open Frankenstein for inspiration, he put pen to paper, even choosing to name the new National album — their ninth studio release — after the incident: First Two Pages Of Frankenstein.

“You can fix a brain, but sometimes it’s hard to fix a soul,” Berninger tells me over Zoom. “I really connected with all the hysterical men in that novel, so it just felt good for the record.”

Playing new songs on tour helped spawn ideas, as well. That’s not typically how things work for the National, but performing a handful of tracks in a live environment allowed them to fully take shape. For instance, the main guitar melody on the relatively uptempo “Tropic Morning News” and the entirety of slow-burner “Eucalyptus” were adapted from the stage to the studio, when it’s usually the opposite for them.

“That is something we’ve always wanted to do on our albums and never have really, so it was kind of interesting,” multi-instrumentalist Bryce Dessner says, on a separate Zoom call. “That’s not to say all of it’s like that, but some of it is, so it ended up being a really good thing to reconnect with each other and with the audience by giving the songs a chance to breathe.”

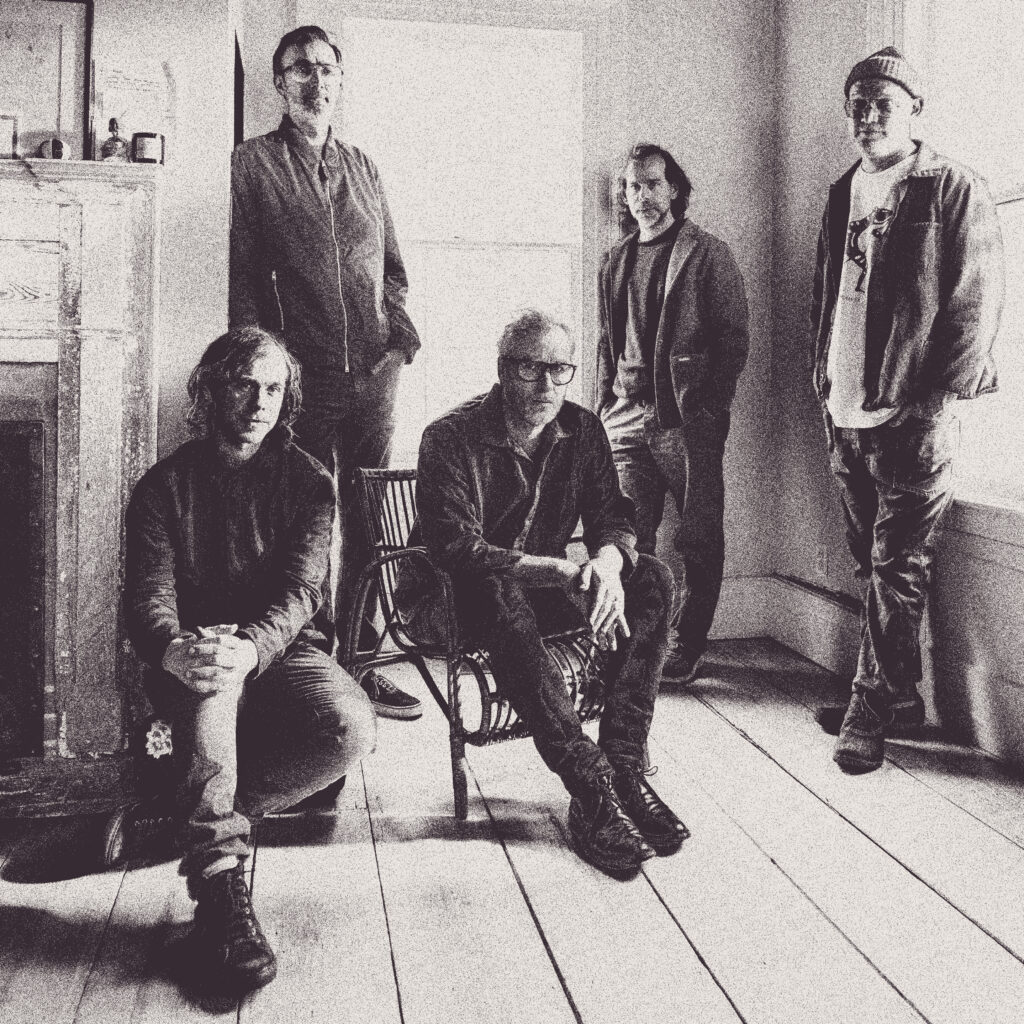

We spoke with Berninger and Dessner about writer’s block, connecting with their audience during live shows, finding solace in collective grief, and reuniting with close collaborators Sufjan Stevens and Phoebe Bridgers.

SPIN: Matt, how did you overcome writer’s block?

Matt Berninger: I wish I had an easy answer for that. At a certain point, I was doing various types of self-care. For a while, I quit drinking and smoking. I was living a very sober existence, and that actually didn’t help at all! I tried a lot of things, and some helped a little bit. It was depression, but with things like that, you have to just go through it and bear with it a little bit. Whatever the block is, it’s hard to turn yourself back on when you can’t. When the wires aren’t connected, you can’t kick the TV to make it work. It was a slow, slow process. Some of it was getting back in the room with the guys and going back on tour and physically reconnecting with people. The creative energy from those guys finally sparked me after a long time, but it was a slow process of untangling whatever block I had. Antidepressants helped a tiny bit, too.

Why did you want to perform some of these songs live before recording them in the studio?

Bryce Dessner: We’re always writing music. We started writing songs shortly after the end of the last tour in 2018. And then the world shut down. The recording process stalled in 2020, and we had over 80 shows that were postponed and then fully canceled. The band sort of went to the wind, and there was no movement for at least a year or so. Matt was struggling with the songs and finding what he wanted to sing about.

Typically, we don’t tour without a new album. But, because the world opened up, we had these concerts, and it became apparent that the record wasn’t done. So last summer, we did a pretty big tour. We had a lot of songs working by then, and something we’ve always wanted to do was play more of our songs live and test them. There are a lot more songs we have that aren’t on the record actually, including “Weird Goodbyes,” which we released last summer with Justin Vernon. But [“Weird Goodbyes”] ended up being a great opportunity to bind things.

Berninger: When “Weird Goodbyes” came out of a recording session, we were like, “That one actually feels like it’s done.” There was a bit of a breakthrough, but it was more so just a crack in the wall. When we got back on tour, I struggled. It took me a while to open my eyes. I was trying to reconnect to it all, and when I’m performing or writing, I have to be in a real place; I have to genuinely be overcome and sucked into it all. If I can’t lose myself in it, I feel like a fraud, and I hate it. I’m always self-aware, so it took me forever just to lose myself again and be able to perform. After about four or five shows into it, it was like warming up in cold water. Then I started writing in the hotel rooms and writing fast. I started to enjoy it again and find what I was doing.

It seems like performing and writing complement each other for you guys.

Berninger: When I’m performing, I have to believe the songs. I have to be connected to the songs. It’s the same thing with writing. I can’t write about anything that’s not actually an issue or a mess I need to clean up. It has to be a real thing that I’m struggling with. I can’t craft a good song unless I’m genuinely feeling it. With performing, I have a really hard time going up there and doing the show by numbers. I have to relive the songs in real time a little bit to feel comfortable up there. And that gets really weird after a long period of time. But it had been so long since I’d done any of that. I hadn’t been in the water for so long that I had forgotten how to swim.

Is that taxing for you to re-enter what you felt when you wrote certain lyrics?

Berninger: Yeah, it is, night after night. It’s a balance. I wish I could stay in that zone the whole show, but I would lose my mind. I have to get really close to it or in it a little bit while performing. It’s a weird thing to sing in front of a bunch of people about your feelings without a guitar in your hands. It’s embarrassing; there’s a part of it that’s totally humiliating. But everybody knows because life is humiliating and miserable. It’s like R.E.M’s “Shiny Happy People.” The only way they could do that song is by knowing how ridiculously unhappy everything is.

People who like the National are all there in that place, too. People are weeping and crying and screaming. Half the crowd is drunk, but a lot of people are in genuinely emotional places. When we perform, I have to meet them there. I have to be there with them or else it feels unfair.

It’s like, these are really difficult feelings, but maybe if we all experience them together, it will make it a little bit easier.

Berninger: Even the act of going into the crowd, which I do a lot, there’s a feeling of connection. Everybody’s emotions are complicated and they’re all different. But, suddenly, you pour everybody’s emotions into the same swimming pool. That’s what the shows are like. I can’t walk around the swimming pool describing it. You don’t know what it’s like to be in the water swimming and splashing by just looking at a swimming pool. Mentally I have to get into the deep end.

What did you do differently with this record that you hadn’t done before?

Dessner: We’ve always been very collaborative. But we came back to a focus on Matt and what the five of us do. Whereas I Am Easy to Find, the last album, had many more guests, vocalists, and choirs, this one is coming back closer to what we do, just the five of us. In general, the process was more supportive. In the past, we were famously combative in the studio, and that’s always been helpful to bounce off each other. But after 23 years of doing that, a little break from that was good. This was much more supportive and constructive. Rather than pulling against each other, we were pulling in the same direction. That felt new and was a good change.

What was it like reuniting with collaborators like Sufjan Stevens, Phoebe Bridgers, and Taylor Swift?

Dessner: Those are all really important people in our lives from different periods of our lives. I played in Sufjan’s band in the early 2000s, and he was really instrumental in Boxer, which is one of our classic albums. He’s all over it, and I’ve played on most of his albums. We share a house together in upstate New York, and he’s a really close friend. When Matt and I wrote “Once upon a Poolside,” I sent it to Sufjan right away. To have him contribute to it, opening the album, felt like a rite of passage as someone who has been part of our family for a long time.

Phoebe Bridgers is an incredible artist who we’ve also known for a while now and has opened a lot of National shows. She was supposed to open our Australia tour during COVID, and it got canceled. It’s amazing what’s happened with her career. Now, we’d probably be opening for her! Taylor has been amazing to work with. What she did with “The Alcott” she did amazingly well and quickly. She’s extremely generous, and we’re fortunate to have friends like that.

What do you think gives this album its own identity?

Berninger: It’s a tender record. I needed a record that was going to be kind to me and remind me what I needed to do. It’s a fetal position record in a lot of ways. I can’t fake it. I cannot go into the studio and turn on Mick Jagger. I can’t Bono it. It has to be real. This record was very much the genuine product of what it had to be for me.

Dessner: It’s emotionally direct in a way that you hear bits of in the past, like “I Need My Girl” or “About Today.” This record, almost all of them have that directness about them. It’s about the fragility of human relationships and human life, but then, the way the album ends on “Send for Me,” or on “New Order T-Shirt,” it’s a love letter to the past. Obviously, relationships change, and nothing in life is permanent. But, in a way, we burnt the house down and then pulled something out of the ashes. The story of this album is like resuscitating an old friend or bringing something back to life but in a new way. After so many years, we keep surprising each other that we can keep going, but we do. I know that our songs mean a lot to people. And they mean a lot to us.