The TV series Portlandia famously opens with the tune “The Dream of the ’90s is Alive in Portland.”

That dream has spread and is now alive (or maybe undead) every fucking place I turn, under every nostalgic jerk and spasm.

I teach at a university, and it’s borderline hallucinogenic seeing students turn up in flannel shirts and desert boots: like I was in 1993.

If anything, the 2020s loves the 1990s much more than the latter ever loved itself. One of the best kept secrets about the ’90s is that it was an era of self-loathing.

People forget that the first half of the 1990s was a portal we used to get back to the 1960s. For fuck’s sake, we all wore peace symbols. But the attempt failed, and it’s not just Woodstock 94 that proves it (let alone the nü-metal Apocalypse Now of Woodstock 99). And then ’60s-redux failed (a bit like the ‘60s itself), we got desperate and tried to get back to the ’70s.

The ’90s, if nothing else, is a decade of failed transcriptions. Time travel, for now at least, is a scam. (If you think the Black Crowes represent the ’90s you’re right: they’re a band trying almost embarrassingly hard to not be in their own era. Nick Cave apparently once spat on them for this.)

Outside the nostalgia, bad faith, and rainbow-barf clothing there was another crucial ingredient: drugs. (If you want proof, ask yourself if anyone who isn’t high would come up with bell bottoms or tie-dyed overalls.) The single elixir which joined Hendrix and the Doors with the Stones and Black Sabbath – and all these to Nirvana and Alice in Chains – was drugs.

So drugs it was, then. That was settled.

For most of my life, before I ever took drugs, I thought about them.

It was hard to be a fan of music without knowing that your heroes were getting hammered. It seemed like heroin, acid, and pot were the steroids of the music industry – performance enhancing drugs. How to think of the Velvet Underground without heroin? You couldn’t. Hendrix apparently even put acid in his headband, allowing sweat to trickle the LSD into his eyes during gigs.

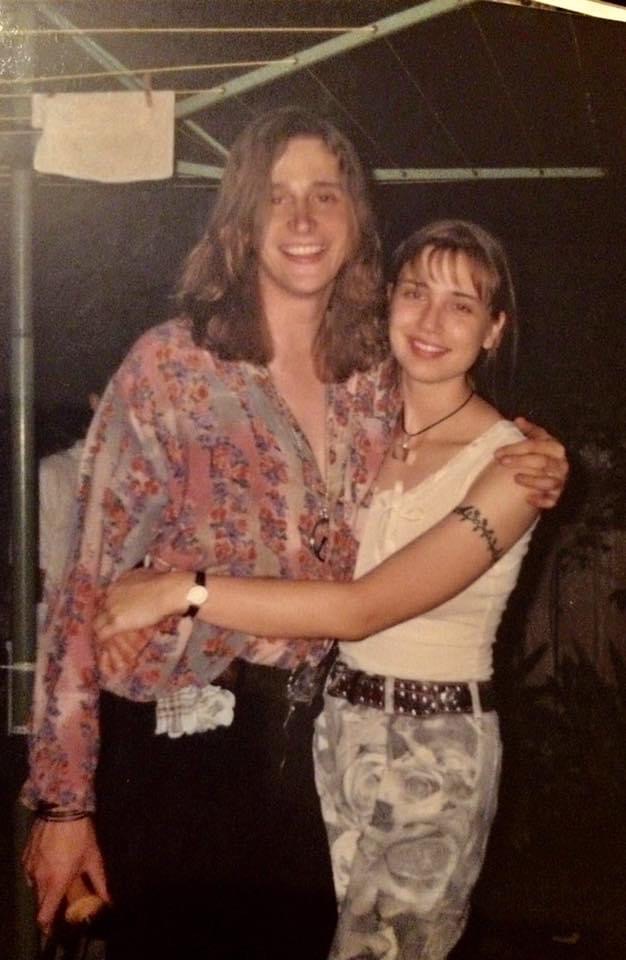

With all that said, I started late. My problem was that rock was all about rebellion and yet, on the ground, it seemed all about conformity. I couldn’t shake the idea that the people into the music I was into were all walking around doing the exact same thing, looking the exact same way.

Torn jeans and long hair struck me as much of a uniform as anything that’d be used in the army, nursing, or ministry – and, given time, those people who were letting it all hang out on weekends would soon enough be doing degrees in finance and working in IT.

And I was right. On these people, only the bad tattoos remained.

And so, for me, the time was right. Just as the people I knew were settling down, calming themselves, having got adolescence out of their system, I was coming around to the idea that it was time to starting fucking myself up.

A friend and I decided that we’d smoke weed and jam. But not long after I smoked I wondered how people could do anything after smoking weed. It was like trying to play basketball submerged in honey. It wasn’t that I was having a bad time; it was just that all I could do was touch the strings. That was enough – to feel the ridges of the metal, the silkiness of the neck, to sit and simply be amazed at this remarkable invention for which Leo Fender (who died in 1991) should have won five Nobel prizes but never did.

What amazed me initially with pot – and drugs more generally – was that they didn’t help you Do Stuff. They just made you feel great without having to do anything at all.

Sitting and staring at a lampshade was enough; better still if you could silently formulate a whole theory of human personality based on that lampshade. A lampshade – or a cat bowl or a lava lamp – contained whole universes which would spiral out unprompted. I was deeply into it.

And as my use increased I found I could do things. Little by little, I figured out how to play guitar high, drive high, teach music, watch movies, even write a PhD high. And by the time I’d figured out how to do all this stuff high, I realized that I’d managed to unlearn how to do any of them straight.

That is, I was a full-blown alcoholic and drug addict.

Decades later, people have nightmare dreams of walking into tests without having studied. I have dreams of being so drunk on stage I can barely stand. Where I’m all scattered mind, watching a body that has forgotten how to be one.

Only in one rehearsal do I remember where another musician made an issue out of my drug use. In the midst of a particularly hard stone, I hadn’t noticed that my dry mouth was causing my lips to get stuck midway down my teeth, looking like some psychopath rehearsing a smile. He mocked that: imitated it. I thought that was very uncool.

It wasn’t just a social mood, one of the faces of cool. The ’90s was an era looser in its control of substances – in Australia you could buy opiates over the counter without a prescription, without explanation, whenever you wanted. Acid wasn’t hard to come by; and pot, although ‘illegal’, was everywhere. To enforce the law, police would have had to arrest whole suburbs. I’d taken it upon myself also, like the French poet Baudelaire commands, to “become drunk without rest.”

Being hammered was more than just cool; it was a musician’s sacred obligation, like having long hair and never smiling in photos.

My body learned to adapt. There were gigs where I skated right on the edge of being able to play at all, to know what song we were playing, to know how to remain upright. I remember being on tour where we were supporting a big band, and it felt like a high-pressure gig. Dose titration was important. Too little inebriation and self-consciousness is out of control; too much and coordination — even the ability to hear — is destroyed. On more than one occasion, I’d fucked myself too hard.

As the drummer counted in on his high-hat my mind went blank: not just on how to play the song, but how to play guitar, how to stay standing, how to blink, breathe, and stay conscious. I decided, if you could call it a “decision,” to just hit all the strings at once, at full volume.

Something about the force of what came out of the amplifier shocked me back into what I was supposed to be doing and somehow it came together. I felt like my guitar had to tell me what to play, in the moment, and it thankfully spoke (or maybe the din woke Bacchus and he helped for a moment).

Many musicians will tell you that their instruments can be like neurotic guard dogs that sniff out fear. There’s an infinite difference between hitting a note or chord which you’ve committed to compared to one which you approach like testing if a plate is hot. A note half-hit, uncommitted to, is a bad fucking note. The guitar will charge you, scare you, send you into a spiral of self-consciousness. It’ll resist you and you will become afraid of it, of making mistakes, of sounding like you can’t play.

The idea is that if you hit a bad note, a wrong chord, you do it again. (Jazz and the avant-garde will forgive this more easily.) Lean in to the sound and be prepared to destroy everything; plant yourself; then lunge into a run.

Drugs afforded me a way of being present in a way I thought I couldn’t be without them, of being inside what we were playing as though it was the music that was playing me, not the other way around.

Research has shown that drugs are not creative aids – and most non-drug heads already knew this. What they do, however, is increase our positive assessment of our own creativity. And for people who hate themselves, as artists often do, this is nectar of the gods.

But by the time I was really hooked, drugs weren’t a way of getting high or feeling great. They were just a way to make reality vaguely bearable.

I remember being in a studio recording a track and realizing that, at 11am, I wasn’t even going to be able to keep my hands still without a liter of alcohol coursing through my veins. That might be rock and roll – but it’s also sad and as boring as fuck. I was, I thought, no different to the guy who works in banking and who can’t get through a human conversation at night without a bottle of wine and three joints.

Rebellion was its own, unique slavery. I ended up putting together a life that was, in short, suicidal and so the relevant question became not whether or not I wanted to get high, but whether or not I wanted to die. It turned out I didn’t.

Getting clean was a nasty hollowing out, a raw-dogging of reality with all its bright lights, sharp angles, and necessary tedium. I’ve written that story elsewhere.

But for years after getting clean I barely played guitar. Nothing felt good, nothing worked. Nothing lit my fuse.

I was in Texas many years later when, tipped off by friends, a bar band invited me up on stage to blow a few solos. I didn’t want to do it, but would have seemed like an ass to say no.

The prospect terrified me. As I rolled the volume nob on the guitar and felt the vibrations of the amp under my feet, I felt like I was going to throw up. And then something happened. I suddenly felt like I didn’t care what happened. It’s a bar band, in a half-empty bar, in a city where nobody knew me.

And then something else happened: an hour and a half of snarling, mad improvisation with four strangers who unintentionally rescued me from my own bullshit.

I was high. Music, it turns out, is enough.