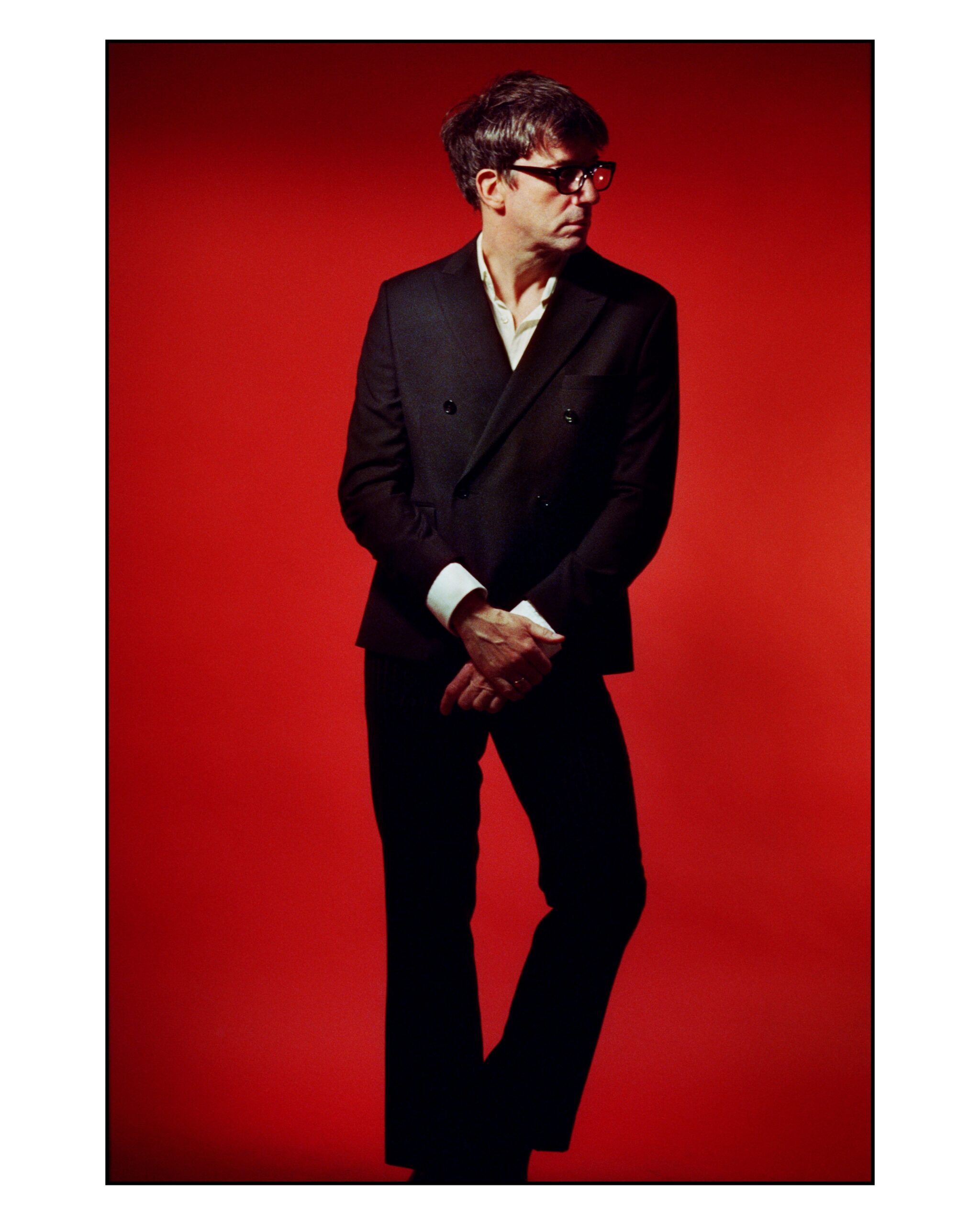

Graham Coxon is in a room so narrow, it looks like a converted closet. The kind of closet in which a kid would hide all their favorite things, and then ensconce themselves in, creating a personal ecosystem. This is what Coxon has done with his home studio in London, England, which houses an array of his favorite items: musical instruments, tools for creating visual art, books.

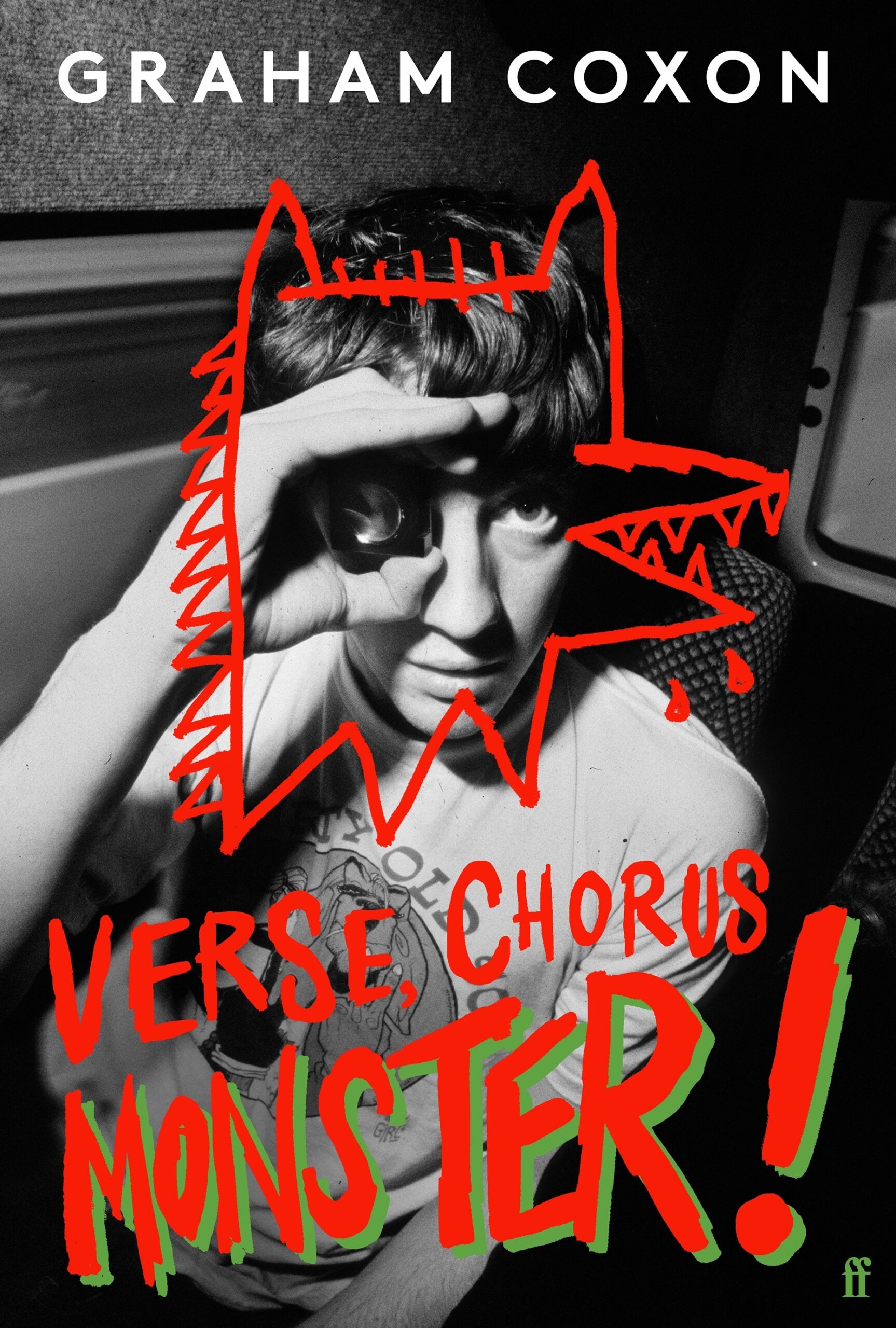

Not visible is Coxon’s recently released memoir, Verse, Chorus, Monster! The fact that the sometime Blur guitarist — as well as score composer and one half of the Waeve with partner Rose Elinor Dougall — has chosen to reveal anything about his personal life in something as public as a memoir is a surprise. Coxon has always been shy and private, avoiding interviews if he can help it, letting his work (or bandmate Damon Albarn) do the talking.

Even with Coxon’s rejection of the spotlight, his battles with mental health and alcoholism are indie pop culture fodder. Verse, Chorus, Monster! doesn’t focus as much on these juicy topics the way autobiographies of members of Guns n’ Roses and Mötley Crüe, or even Moby, do. Instead, it is a relatively tame and occasionally humorous look at his downfalls. Coxon expounds on songwriting and guitar playing, an approach to memoir-writing that’s just right for the far-reaching “Cult of Coxon.” These are the same fans who are protective of Coxon as a person, don’t want to intrude on his privacy, and are interested in the minutiae of his working process.

Initially, the book was going to be a collectible one featuring Coxon’s extensive visual art. But as Coxon says, “That book would probably sit on a shelf or a table, never get opened and get coffee marks on it. It needed to be more than that.”

He teamed up with experienced music writer and editor Rob Young, known for Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music. They met over Zoom, for three- to four-hour sessions a couple of times a week, over a period of many months, and Coxon would just “talk and talk.”

Right before these meetings began, Coxon was living in Los Angeles, where he hit mental rock bottom. “People have to work so hard just to exist there, let alone anything else,” he says of the city. “I was doing soundtracks, but the place was crawling with people like me, like ants. I felt like I was disappearing. When I’m in London, I feel like a slightly bigger animal, more like a dog or a cat.”

Coxon is quick to point out that it was not Los Angeles that was the problem, but himself. At home in London, with his three daughters, is where he is at his best. Between intermittent puffs on a vape, Coxon tells SPIN some of the things he left out of Verse, Chorus, Monster!

SPIN: Why was this the right time to write a memoir?

Graham Coxon: In 2020, my life reached full calamity. I had to think, “What have I been doing wrong up to this point?” I had gone far up the wrong road for so long, I didn’t know how I was ever going to be able to find my way back onto the right road. It seemed like a good time to put that into perspective and meditate on what might have gone wrong, and what I can do to make my life better.

Did working on the book help you back on the “right road”?

There’s a lot of hanging over from before Verse, Chorus, Monster!, but I am different from who I describe in that book — in good ways. The issues I had and the things about myself that got me into trouble, I have recognized and done something about. It’s a shame that building up self-worth came so late in life. It takes a lot of effort. It’s easy to be lost and tossed this way and that way by life and think you’re reasonably happy, but not knowing what life could be. That’s what the book is: not having that insight, or ignoring your own insight, ignoring your gut feelings about your life in order to stay in chaos, in a comforting negative life. I was having therapy every day from May 2020 until the other week.

Therapy was happening alongside writing the book? That’s a lot of self-discovery all at once.

Yeah, it’s a bloody lot. Sometimes you’re so far out onto the hook that you can’t get out for years because you don’t even realize you’re in a situation that’s bad for you. That’s a sort of a brainwashing. It’s hard work rewiring what’s been hardwired. I’m not sure you can really rewire your template once it’s been there. I don’t think anybody ever really manages it. They just sort of learn how to recognize things about themselves that are not doing them any good and take a route around it. But the book and therapy helped me examine how I got to that nervous breakdown, and how my mind just fell apart around this time three years ago. I could just feel it falling into bits, and it was a really weird feeling. I had to remove myself from a situation that was causing it and get back to the U.K. and have my nervous breakdown in a familiar place where friends were and start thinking about what to do.

It feels like in the book you skim over your personal relationships with your partners, and even with the other members of Blur, a bit like a respectful distance from them.

People who I’ve really loved and a lot of the amazing and beautiful formative friendships that I had didn’t make an appearance. I want to keep some stuff to myself. If I went into that world, that would be getting into other people’s lives that maybe wouldn’t appreciate me talking about them that much. But I don’t think I’ve ever fallen out with anybody badly enough or have wrestled with so much resentment that I would ever want to say anything nasty about anybody.

Similarly, when you speak of your addiction, you do it in a reserved way, not getting into the dark spaces the way some musician biographies have.

The fact is, I wasn’t homeless in London shooting up in a doorway. I just drank a bit too much and fell over in the street, bashed my head. and made an idiot of myself. I tried to get into fights but didn’t succeed because whoever I was picking on — I picked on some big, mean guys, wanting to get into a fight because I wanted punching — they were too reasonable to fight me.

Alcohol did a fine job for me, but it was bad enough to make me mess up relationships and my band to get angry with me, but it wasn’t catastrophic. I could always see, “Shit, it’s been four months. I can’t seem to get off this bender. I better see someone.” It’s not a nice feeling when you can’t get off that horrible daily merry-go-round of knocking the edges off your hangover and then not being able to stop drinking.

I miss pubs. I miss that time on your own drinking, starting inappropriate conversations with strangers. Something almost spiritual happens to your mood. But I know what comes next after those three hours. You get into trouble talking to strangers. You end up in weird places, and then you escape out of a window, and you don’t know where you are in London. There are no taxis, and you’re walking home for two or three hours not knowing where the hell you are. It’s not great.

From everything you’ve said, it’s surprising you didn’t abuse drugs.

There wasn’t an awful lot about myself or my childhood or my upbringing or how I was feeling or my mental health to want to smother with drugs. I know what drugs would have my name on them because of what I’ve had as a prescription given to me by a nice nurse where I thought, “Wow, I could really get used to this.” After taking that, I realized, “Ah, this is why you see people shuffling down corridors in those films. I’m doing that. I’m boiling the kettle to make some tea and I’m missing the mark, and that boiling water is going onto the counter onto the floor.” I could have got used to that.

I didn’t want the book to be really heavy. I love a laugh, and I’m actually quite funny. I’ve gotten through hard times by acting silly and being fun and finding some sort of humor in everything. That’s a big part of who I am, so I had to have some funny stuff in there, too.

What do you hope people will take away from Verse, Chorus, Monster!?

I thought I would put a pamphlet in the book, “Musician’s Guide to Dealing with Fame,” or something like that because I kept finding myself saying, “I wish somebody had told me, had warned me, in 1991, had said, ‘This might happen.’”

When we started in ’90, a lot of things weren’t talked about because they weren’t known about. You might come across people and be warned, “Careful, they’re trouble.” But not very often. Someone who’s basically been in their bedroom practicing the guitar and is suddenly out there, amongst all of that, is very vulnerable. I didn’t know about boundaries. I was a people pleaser. I didn’t want people to dislike me, so I didn’t like saying no. I didn’t want to hurt people’s feelings. No one told me it could get you into some really bad situations, and you’ve got to learn to say no and to have some boundaries, and you’ve got to really be able to look out for those people who are who are out there to cause you harm, even if they’re in the guise of people that that are wishing you well.

I liken it to Homer’s Odyssey and how going on tour was a similar thing with sirens and assailants and Cyclopes and witches and seductresses. It’s a dangerous world because it seems like fun, and quite often it is fun, but things can happen, and it is not fun, seriously not fun.

For everything you went through to get it out, your book is going down very well with fans of course, but also with critics. You’ve got some great reviews.

I don’t think I’ve ever really had terrible reviews. I’ve tried to be as authentic as possible with music, and I tried to be authentic with this book. Journalists can sniff out authenticity. The book is honest. It comes from my skewed point of view over the last 53 years. I can’t be objective, no one can. But, hopefully, it’s a decent account of everything.