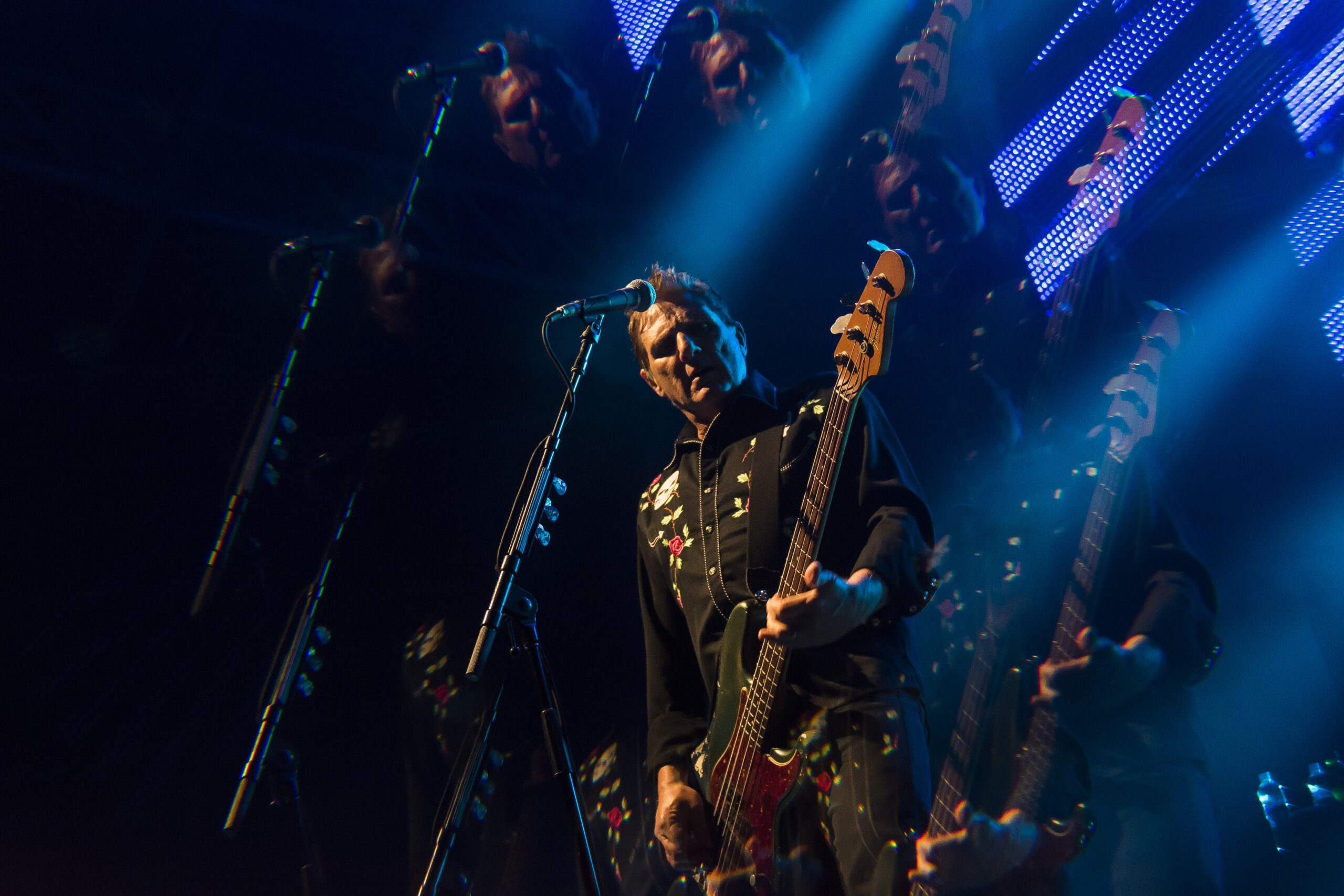

Hoodoo Gurus bass player Rick Grossman is trying to land two scorching mugs of coffee onto a dining table so big it should have its own zip code. “Hang on, mate. I’ll make some room.”

Making room involves first shoving clear Cormac McCarthy’s recent tome, The Passenger, and Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song. The blue 1965 Fender Precision bass stretched out on the table, however, gets more TLC.

Grossman carries it lovingly into his home office in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, where it resides in a phalanx of guitars. The instrument was purchased in NYC in 1989, when the Hoodoo Gurus first started touring the US. Its patina is now patchy, worn down to the wood in some parts.

Not unlike its owner.

In truth, though, Grossman looks way better than the instrument. He’s in one of his signature paisley shirts and has just spent the day in a rehearsal studio with fellow Hoodoo Guru, drummer Nik Rieth, preparing for the band’s American tour in April.

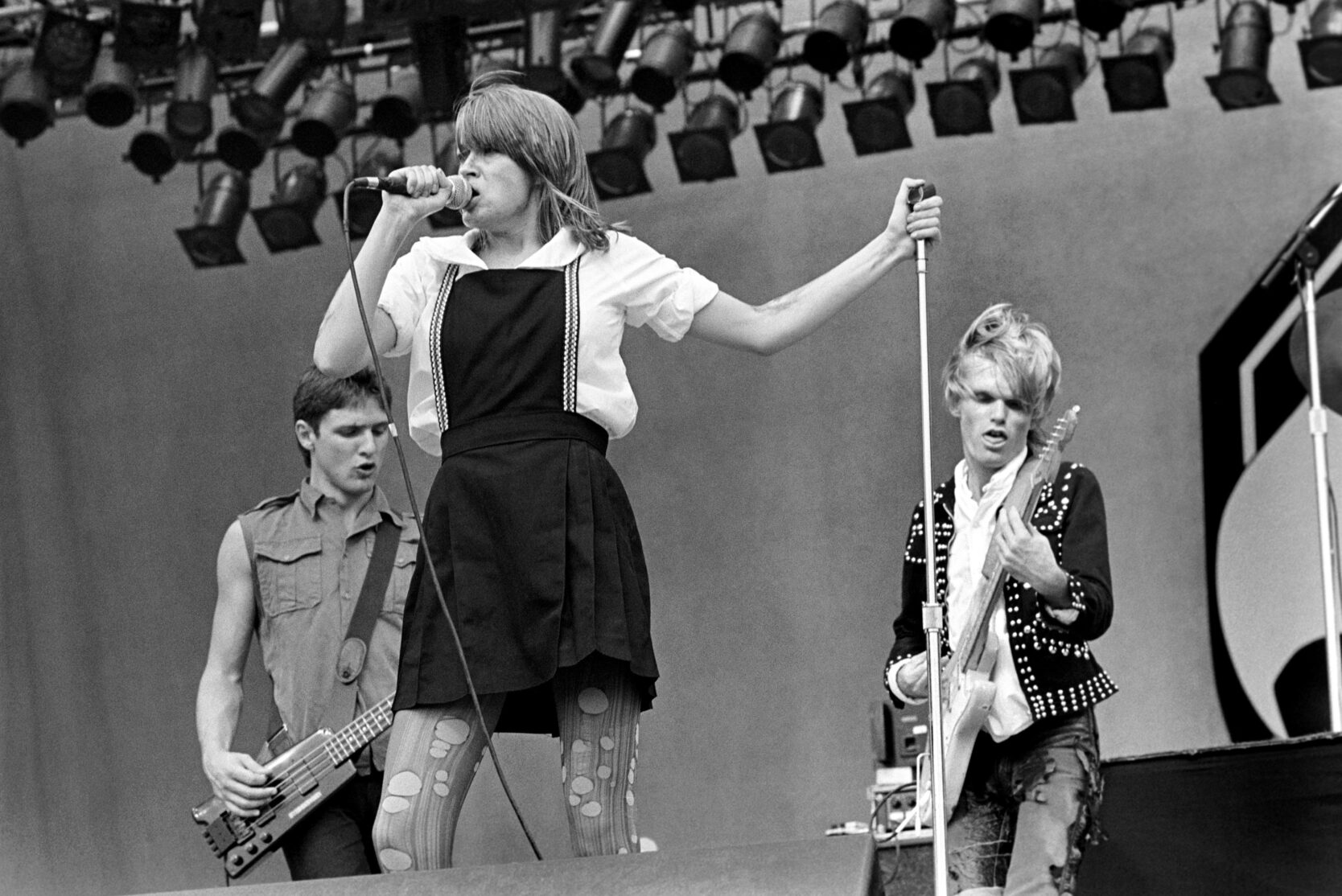

Grossman is one of Australia’s most prodigious musicians, stepping his way up through numerous successful bands including Bleeding Hearts, Eric Gradman’s Man and Machine, and Matt Finish. In 1982 he joined the Divinyls, then six years later Hoodoo Gurus. There is also an ongoing side project – Ghostwriters – with Midnight Oil drummer Rob Hirst.

He has never made any secret of the fact he was a heroin addict for years. However, it was his sojourn in the Divinyls when his drug habit really cut loose.

SPIN: How was drug use for you initially, before it became a problem?

Rick Grossman: We’d be a bit obsessive about buying hash that used to be around in the ‘70s. I never ever thought of it as a problem. My life seemed quite full with music, and dreams of playing music, and dreams of being successful at music. Drugs were just there; it didn’t seem to be much of an issue.

In the mid-‘70s the guys I started playing with, who were quite a bit older than me – they were all into heroin. And the first time I ever used heroin I smoked it and absolutely loved it, but didn’t seem to crave it or think about it all that much. I had it for maybe two weeks and we were playing music, and then I went back to my hash and didn’t really think about it for another few years.

What were you doing at the time that you reconnected with heroin?

Well, heroin was always around. Before I went to Melbourne [in the mid-70s] there was a bit of acid and Mandrax [Quaalude] tablets. I never really liked being out of control. I had a few blackouts on alcohol, but they kind of scared me. Waking up somewhere strange. How did I get here? What did I do?

When I went to Melbourne, I was playing in a band that was in what I used to call the ‘macrobiotic junkie scene’. They were all share houses, lots of kids, lots of feminism, alternative theater. And a lot of heroin.

In 1978 I met a girl who was heavily involved in heroin. She stole everything out of our house. She overdosed in my bedroom. I thought I could save her. She had been in a relationship with this gangster. And I was like this kid who didn’t know what was going on, and I thought I’d be able to get her to stop. I was wrong. [Laughs]. I mean, it was chaotic. I still don’t know – it’s, it’s a mystery to me.

I came back to Sydney at the end of 1979 and started playing with Matt Finish. Then my dad died. I remember being at his funeral and not really feeling like … I wondered why I wasn’t crying. If I look at the timing, stars have to align, I suppose, for things to happen. But he passed away early 1980, and that’s when my heroin use really took off. And it happened to be quite available. I was using it casually on weekends, [laughs] but that didn’t last very long. It was still a fun thing. And I was traveling a lot.

I liked it.

How did the drugs affect you mentally?

Chrissy [Amphlett, the Divinyls’ lead singer] said that I became very silent; that I was quite social at the beginning of the Divinyls and that [now] I didn’t have a voice anymore. I felt scared a lot of the time. I felt ashamed a lot of the time. I felt I had this secret that I liked having, but I didn’t like myself very much.

I used to feel this kind of melancholy for my younger years: before drugs had come along; before people had died. You know, the stuff that comes along with heroin: the jails and violence – and it was happening to people that I knew. I just shut down and thought I’ll keep my head down and just to try and manage it as well as I could. We’d have band meetings and be discussing the artwork for some record or something, and I’d look at the artwork and I’d think, “That’s awful.” And they’d say, what do you think Rick? And I’d say, great. I didn’t want any confrontation; I just wanted to be left alone to do my job. It just eroded my confidence and self-esteem.

When I said that I needed some time away from the band, Chrissy was actually shocked, but she had her own demons, so I’m not surprised she didn’t notice.

But life was a whirlwind in that band, so they weren’t really noticing too much. I didn’t like being out of control, and for the last few years my using was all about trying to feel normal. It wasn’t about parties.

When I was left alone in a hotel I wouldn’t nod off and set fire to the bed or do something stupid like that. But I was really obsessed with trying to appear okay. And I got so tired of it. I got so tired of having this facade and this thing that I couldn’t talk to anybody about and it was getting bigger and bigger. This malevolent dark thing. My health was bad, I was overdosing; all that stuff that comes along with heroin addiction.

What was your lowest point?

Man, there were quite a few. I knew I was in trouble maybe two years, three years before the end. My self-esteem had gone right down. And I just wouldn’t look at anyone in the eye. I’d just avoid: avoid people, avoid situations unless I really had to. I’d go to band meetings and wouldn’t say much.

We were playing in Brisbane. I was on my second day of no drugs. I was sick, so I manipulated this whole scenario and someone from our management’s office was coming up from Sydney, and I got a friend to drop off to him a very important cassette that I needed. He didn’t know what was inside. It had a syringe and some dope in it. I was waiting all day for this guy to arrive. And we had to drive out to the gig and he handed me this thing just as I got in the car. We get to the gig. I find a toilet and think I’ll just have a little bit to stop being sick.

When I got dressed, got on stage, well, it was awesome. It was like Popeye with this can of spinach. Felt great playing away, thinking what was all that drama in the last few days about? I looked down, and there’s a trickle of blood coming out of my arm, and mate, something inside me just died. I was just shattered. I know that it sounds corny to say it, but it’s like your life flashes before you. All those dreams as a kid.

Did drugs have any benefit for you as a musician?

When I teach at university, if I’m talking to younger musicians I’ll say, “Look, it always ends in tears.”

I mean, if you look at different movements of music over the years, they’re all fueled by drugs. In the ‘50s it’s amphetamines and speed. The ‘60s: there’s pot and acid, and then there’s coke and heroin in the ‘70s in New York.

But it always ends in tears. Promises a lot at the beginning. Promised me a lot, I guess, right at the beginning. I loved smoking dope and listening to records. I dunno if it really improved me as a musician or anything like that. I doubt it.

I remember when I first got sober and had to go out and start playing with nothing. That was pretty confronting.

In what way?

You’re on a stage with nothing. You don’t have any cushion between you and what people are thinking of you. The most important thing [to me] was what you thought of me, not what I thought of myself.

A therapist had said to me, once you put more value on what other people think of you than you think of yourself, you’re in trouble. And I’d always been like that. When I was a kid I felt invisible, and I spent the whole of my life trying not to be invisible.

And so when you take all that stuff away and you’re standing there with no anesthetic and no cushion, it’s raw.

But I loved it, and I have no doubt that I’m a much better musician without it. All this romantic stuff – the poet in the garret sitting on a bed with a needle in my arm writing great songs: I don’t really buy that.

You know, I had many friends who have died and, you know, one of them was a beautiful guy, Ian Rilen [from Rose Tattoo] who, if he was given the opportunity, I’m sure he’d want to be alive now.

But it was all those sorts of people around going, “Oh it’s rock and roll and I have to be wasted.” I don’t really buy into that stuff. There’s nothing glamorous about being in detox in a pair of old men’s pajamas. All that stuff goes out the window pretty quickly when you start thinking, “Oh, this is really cool.” I didn’t think it was very cool.

Was there any kind of epiphany in any way?

When I was detoxing in the Langton Center [in Sydney’s Surry Hills] I remember being in a group and people were saying “I used because my mother didn’t love me enough,” or “I used because this happened, or that happened,” which well may be true.

But this great woman working there said: “No, you used because you want to.”

To not do something that I wanted to do was an alien thing. Learning a different way of living was profound.

As far as spiritual experiences or epiphanies, I’ve never seen a burning bush or anything. But I know that I was about nine months clean – I got clean [for the last time] on July 3, 1990 – and I was away playing [with the Hoodoo Gurus] and white-knuckling it in a way, and thinking I just can’t do this. And sometimes I’d want to be able to have a drink or get away with something – but I didn’t. I was in recovery and doing all the stuff that I had been told to do, the actual actions.

One day I was on a bus and one of the crew lit up a joint. I just realized I didn’t want to do it anymore. It was incredible. I’d gone from “I can”, to “I can’t”, to “I don’t want to”, which is a 180 degree shift.

That was a real freedom moment for me. I wasn’t sitting there holding a crucifix up to the guy like the devil had appeared and he was smoking a joint. I just didn’t want to do it. And I haven’t since then. Haven’t considered it.

How was it transitioning from the Divinyls to the Hoodoo Gurus?

I felt free of the addiction. It was joyous when I first came around to recovery, and I first experienced that freedom.

One of the guys [from recovery] had a food delivery business, and he said, “Do you want a job now?”

You come from playing in New York and being in nightclubs with whoever, you know, different people and all that stuff you do, and he says “Do you want to deliver pizza?”

So I was driving around Sydney with a walkie talkie – no mobile phones. There were like five of us, delivering food, and it was hysterical. I mean, everyone there was mad and laughing, and some of the experiences you’d have delivering food were pretty funny. Driving down William Street one night, a car pulls up next to me, and it’s [rock band] Hunters and Collectors, and they call out to me. And I said, “Where are you guys going?”

And they said, “The ARIA awards.” [Basically, the Australian Grammys.] They say, “What are you doing?”

And I said, “Taking some pizzas into the city.” And they all looked at me – like “What?”

That was humbling experience. I had a little pang, looking at them thinking, “Oh, wish I was going to the ARIA awards, too.” You know?

I hate the Aria awards, really, but, you know, I wished I was going. But I also felt this freedom that was great.

How is life on the road sober?

Well, when I went to audition for the Gurus I didn’t realize everyone in Australia wanted to be their bass player. I went in there, and they said, “We’ve seen you play in the Divinyls many times. We know how you play, but it’s what we’ve heard about you with your drug use.”

I was nine months clean. I said, “If I keep doing what I’m doing each day, I’ll be, you know, I should be okay.”

They said, “Fair enough. What’s your favorite movie?”

I said it’s Dr Strangelove.

And they said, “You’re in the band.”

We have fun. We are like tourists. We go and look at things and have a laugh about stuff. When we’re all rolling along and it’s all good, we have this great fun and sense of humor, you know? Like the Dr Strangelove thing. It’s important in our band. I’ve worked with other people where I’ve said the same stuff and they kind of look at me blankly, you know, saying jokes or references to TV shows or whatever, and they just don’t get it. They just look like, “What are you talking about?”

But we’ve also gotta be able to get away from one another. We need to have some space. I like watching Netflix or movies. I read books and just shut off.