Baked into the creation of any conceivable list is the competing personal agenda(s) of its curator(s) and the crushing self-awareness of how an intended audience might receive it. These realities arguably craft (or warp) the final product into eventual rough-hewn shape, released naked and vulnerable as it demands or pleads validation from those who might peruse it. This is not to say lists are inherently inauthentic or embellished, but for those who take the time to craft them, there’s intention, purpose, and even passion to impart not only expertise but connote an automatic, respectable level of taste.

Year-end best-of lists are lightning-bolt shortcuts into a person or entity’s thought process, some lists esteemed enough to become heralded. It’s difficult not to be overwhelmed by the glut of (usually) high quality artistic or auteur endeavors which flood theaters every fourth quarter. The trick works, especially for awards consideration. Our minds can only remember so much. But few things are more boring than lists which fall prey to this timing gimmick. And as far as what potentially defined the year 2022, where cinemas and film festivals were, somewhat, able to shake off the big chill instilled by the pandemic, it was a year of cinematic delights like any other — you only have to know where to dig. And this is where lists become veritable guides to the truffles.

Not quite breaking into the top 10 of this list is an odd assortment of players. Angus MacLane gave us an unexpectedly touching Buzz Lightyear origin story in Lightyear, while David Cronenberg returned from hiatus for a new exercise in body horror with the loquacious and strange Crimes of the Future. Owen Kline (son of Kevin Kline and Phoebe Cates) unleashed the ghost of Fellini on Trenton, N.J. in the uncomfortable Funny Pages, while artist Martine Syms’ debut, The African Desperate, is an entertaining, drug-fueled jaunt for one newly-minted MFA grad.

And then the eternally watchable Claire Denis presented not one but two new films this year (winning festival awards for both), reuniting with Juliette Binoche in the relationship drama Both Sides of the Blade and then pulling a Peter Weir for her English language debut, Stars at Noon.

A film which would have secured a slot in this top 10 — but is not receiving a qualifying theatrical run (outside of Iran’s official submission qualifying for an Oscar nomination as Best International Feature) — is Houman Seyyedi’s World War III, a grueling and complex tale of cinema, despots, and despair.

10. The Good House, Dir. Maya Forbes and Wally Wolodarsky

Somehow, Sigourney Weaver really was everything, everywhere, all at once in 2022. Unfortunately, the cultural conversation of her contributions will be eclipsed by the long-gestating arrival of James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water (in which Ms. Weaver plays a 14-year-old character and filmed lengthy underwater takes for a motion-capture performance). But she also appeared in Paul Schrader’s subversive Master Gardener, premiering at the Venice Film Festival (slated for theatrical release in 2023); Phyllis Nagy’s timely abortion drama Call Jane; and the highly underrated The Good House (which preemed at the 2021 Toronto International Film Festival and wasn’t scooped up until nearly a year later by Roadside Attractions). Based on Ann Leary’s (wife of Denis) acclaimed novel, the script was initially adapted by Michael Cunningham (The Hours, 2001) for a Meryl Streep/Robert De Niro reunion until it was repackaged for husband and wife team Maya Forbes and Wally Wolodarsky to direct, with Thomas Bezucha (Let Him Go, 2020) re-writing. An example of how a finely wrought performance absolutely elevates a film, this somewhat lighter take on the Leary novel gives Weaver one of her finest roles in years, devouring the material as an alcoholic in denial reuniting with a former flame (her third pairing with Kevin Kline following 1993’s Dave and 1997’s The Ice Storm). Deliciously breaking the fourth wall in ways which invite the audience into dangerous complicity, Weaver is vibrant, compelling, and sensual. There’s an odd mixture of Sirkian fatality (think the meddling, class-oriented children of All That Heaven Allows or There’s Always Tomorrow) with the inevitable despair of The Lost Weekend. At a point in time, Weaver’s performance would have been automatically earmarked for an Oscar campaign. To crib from Tennessee Williams’ The Fugitive Kind, “This country used to be wild; now it’s just drunk.”

9. Barbarian, Dir. Zach Cregger

Wow. An increasingly rare feat in the horror genre (particularly in American cinema), Zach Cregger’s debut, Barbarian, certainly surpassed expectations by combining Hitchcock’s Psycho-switch with Josef Fritzl-inspired traumas. While it’s a stellar calling card for Georgina Campbell, Justin Long gives one of his best performances in years (despite playing a similar character in Neil Labute’s abysmal House of Shadows), with Cregger’s script layering various motifs and gender disparities into the fabric of a film ultimately about moral dilemmas and how men seem hardwired (or simply allowed) to fail them. Not without a sense of ludicrousness, Barbarian takes logical terrors to the extremes in the outskirts of defunct Detroit, and spackles it beautifully with the best use of The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” since Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973).

8. Resurrection, Dir. Andrew Semans

If you missed Andrew Semans’ 2012 directorial debut, Nancy, Please, you’ll definitely want to check it out after the bizarre mind games afoot in his Resurrection, led by yet another disturbing and distressing performance from Rebecca Hall, a woman whose emotional well-being is literally pock-marked by the toxicity of a past lover who irreparably warped her well-being during her formative years. Existing on the same wave-length as the screeching spouses and slimy sex creatures of Zulawski’s Possession (1981) and the imaginary child of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, it’s a remarkably unsettling portrait of the potential damage inflicted by romantic liaisons — and how some psychological scars never truly heal.

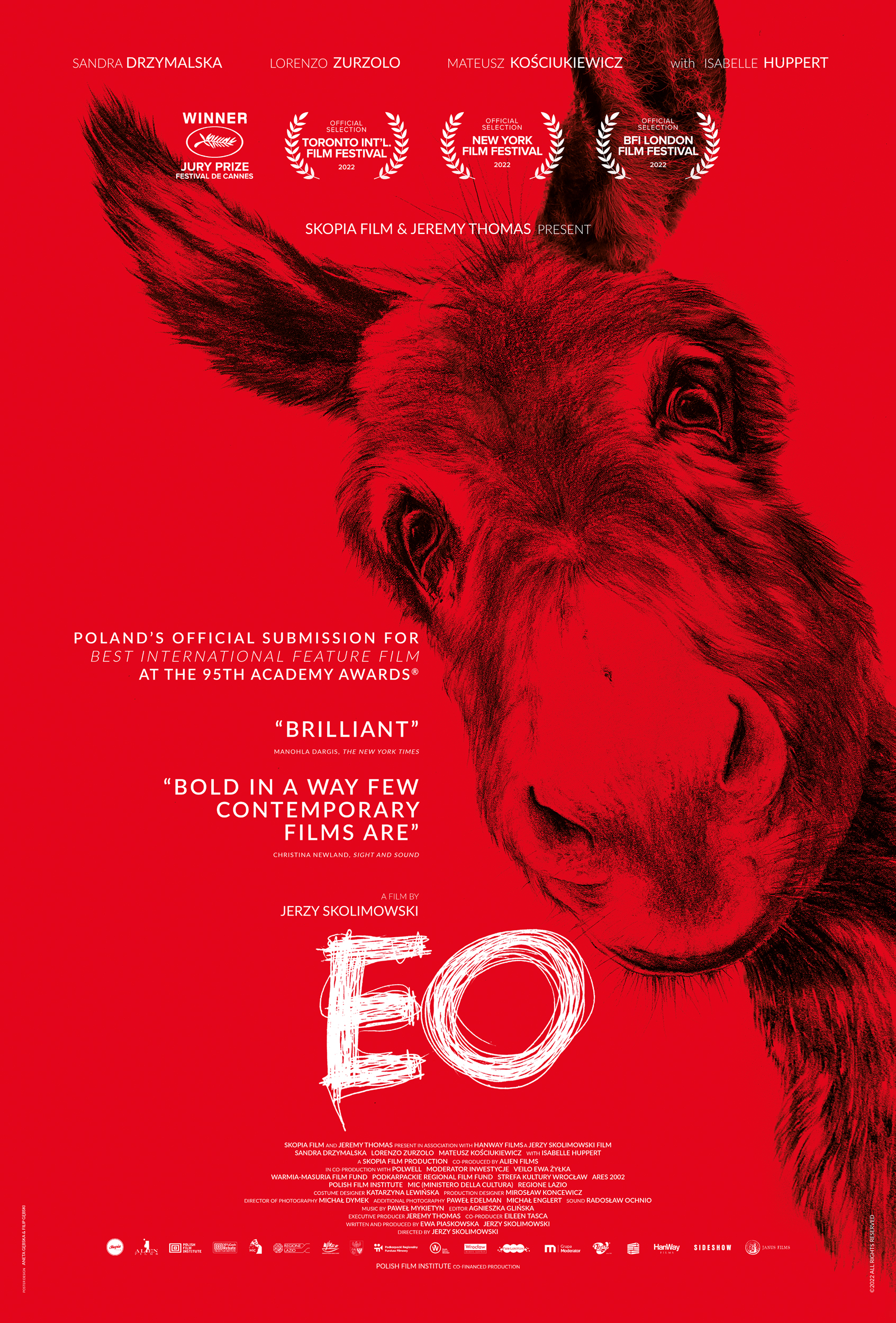

7. EO, Dir. Jerzy Skolimowski

He’s one of the titans of the Polish New Wave, and even in his ‘80s, Jerzy Skolimowski somehow feels more refreshing than ever in his latest offering, EO, which co-won the Jury Prize at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. It’s a hard sell for sure, technically a rehash of Robert Bresson’s 1966 classic Au Hasard Balthazar, which follows the trials and travails of an abused donkey. The narrative scope is the same for this titular animal, supposedly “rescued” from being a circus performer in Poland only to be cast into hard labor, traveling to Italy (where he is briefly owned by the stepson of a luminous countess played by none other than Isabelle Huppert), ending up in a procession to the slaughter house (in a sequence highly reminiscent of the fate reserved for the doomed Alain Delon in Mr. Klein, bustled off into the Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup). Transfixing cinematography from Michal Dymek and a vibrant score from Pawel Mykietyn combine to make a sublime cinematic experience — yet another recent offering from Skolimowski proving he’s lost none of his visual flair or fervor.

6. Donbass, Dir. Sergei Loznitsa

It only took a war on Ukraine for Donbass , Sergei Loznitsa’s engrossing, if difficult 2018 title, to receive U.S. distribution. Originally opening the Un Certain Regard sidebar at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival (where Loznitsa was awarded a Best Director prize), this stunningly uncomfortable black comedy showcases how propaganda and fake news have literally eroded reality to make way for brutality and utter chaos in this titular region of Eastern Ukraine. If you’re a fan of Emir Kusturica’s Underground (1995), or any number of Fellini’s caricatured spectacles, Loznitsa’s neglected masterpiece is must-see (and his 2017 Dostoevsky adaptation, A Gentle Creature, previously adapted by Bresson, is also highly uncomfortable and deliriously strange and still in need of U.S. distribution). Lensed by Romania’s Oleg Mutu (who shot Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days, reuniting with Loznitsa here), it’s a film as dizzying as it is disconcerting.

5. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, Dir. Laura Poitras

Academy Award-winning documentarian Laura Poitras took home the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for her unexpectedly profound All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. Technically a portrait of an artist’s call to activism during the opioid crisis, it is really a more complex portrait of humanity ensconced through the lens (and personal experiences of) photographer Nan Goldin. Weaving personal experiences and traumas, Goldin’s personal history is a battleground of the misogyny and homophobia underlining our established heteropatriarchy. “Through Goldin, Poitras shines a light on the victims of the opioid crisis as humanity’s canaries. But the underlying tragedy of her documentary showcases how the egregious greed of the Sackler family produced a devastating healthcare crisis. Together these juxtaposed elements create a heady mix of macro and micro, personal and political. Simultaneously, Goldin’s through line provides a snapshot of everything from the deadening realities of 1950s suburbia to the decimation of the AIDS crisis to a recuperation of many artists and icons lost along the way (including touching tributes to Cookie Mueller and David Wojnarowicz).

4. Saint Omer, Dir. Alice Diop

Few have achieved as steady and unflinching a gaze into the abyss as Alice Diop with Saint Omer, technically her narrative feature debut following the celebrated documentary We (2021). Her latest borrows from the actual French court case of a woman named Fabienne Kabou, an immigrant woman charged with the murder of her infant child. Diop creates a heavily layered and intricately mannered courtroom drama around a novelist who decides to cover the trial as an exploration of the Medea mythos. While obvious micro aggressions and racial tendencies of a largely white, French community abound, especially in the young woman’s defense of claiming to have been bewitched, this is also a contemplation on the complexities of motherhood, filtered between the gaze of two women: one listening, one speaking. As the novelist, who has significant issues with her own mother, Kayije Kagame is a striking screen presence, pondering her parallels with the woman on trial. An exceptional performance from Guslagie Malanga, who sails through extensive takes filled with loaded passages and fluctuating emotions, will have you transfixed. Lensed by Claire Mathon and co-written by Marie N’Diaye (White Material, 2009) and Diop’s editor Amrita David, even before you get to the defense attorney’s show-stopping closing statement on monsters and motherhood, you’ll already have experienced a new cinematic masterpiece.

(Credit: Carole Bethuel / Les Films Pelléas. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.)

3. One Fine Morning, Dir. Mia Hansen-Løve

While fans of director Mia Hansen-Løve have perhaps come to expect a certain level of compassion and finesse in her output, she rivals the beautiful melancholy of her 2016 offering Things to Come with her Cannes-premiered One Fine Morning (which picked up an award out of the Directors’ Fortnight). The estimable Léa Seydoux delivers one of the year’s best performances as a single mother struggling to secure a spot in a decent nursing home for her father (the great Pascal Greggory), a professor suffering a debilitating neurodegenerative disease. Simultaneously, she acquiesces to an affair with an old love interest (the eternally dapper Melvil Poupaud).) Hansen-Løve has a way of expertly conveying the most delicate of human emotions and experiences without seeming forced or labored — it’s akin to capturing life itself. You can try and keep your eyes dry, but what would be the pleasure in that? And for those book lovers out there, Hansen-Løve sees and understands you…

2. TÁR, Dir. Todd Field

By now, audiences may have already bolstered themselves for the storm that is Cate Blanchett as composer Lydia Tár. But for those walking in blind to Todd Field’s first film since 2006’s Little Children, the Venice-premiered TAR was a delightful assault. It was no surprise Blanchett won her second Volpi Cup for Best Actress (after Todd Haynes’ 2007 I’m Not There), but this hand-tailored exercise for the performer is not only absolutely captivating, but fascinating and comprehensible despite the fussy, esoteric universe it’s mired within. “Disturbingly aspirational despite her repellant disparagement of others and her monstrous narcissism, the character of Lydia Tár is an irresistible study on cancel culture and the abuses of power.” Nina Hoss, Mark Strong, and Noemie Merlant are nice accents in the supporting cast — and they, along with the city of Berlin, are devoured by Blanchett. This is “Isabelle Huppert in The Piano Teacher“ level characterization, an homage to predators run amok.

1. Everything Everywhere All at Once, Dir. Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert

At the core of this intensely manufactured, brilliantly executed character study masquerading as an adventure film, Everything Everywhere All at Once may be the most inventive take on a woman’s bittersweet attempt to ponder a life she might have had if only she’d followed her own desires. Directors Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (aka Daniels), re-teaming from their comparably gonzo mix of pain and poignancy with Swiss Army Man (2016), center this restless hurricane of a film on the shoulders of a never-better Michelle Yeoh, who fluctuates mightily from droll snipe to agonized parent. Aided by Stephanie Hsu, James Hong, Ke Huy Quan, and a gut-busting performance from Jamie Lee Curtis, to describe the plot mechanics of a woman caught in the throes of an existential multiverse might sound like a hyperactive headache to some. But it’s brimming with ideas, laughs, and an obscurely eloquent examination of humanity, promising exactly what its title suggests by gently tossing us into a tenderizing spin cycle. While the vibrancy and intensity might be more than some prefer, Everything Everywhere All at Once feels like its own special entity, and for those susceptible to its vast charms, you’ll be reduced to a teary ganglion of googly eyes.

Watch Nick and his husband Joseph review (and spoil) films on their YouTube channel, Fish Jelly Film Reviews. Their podcast of the same name is available everywhere.