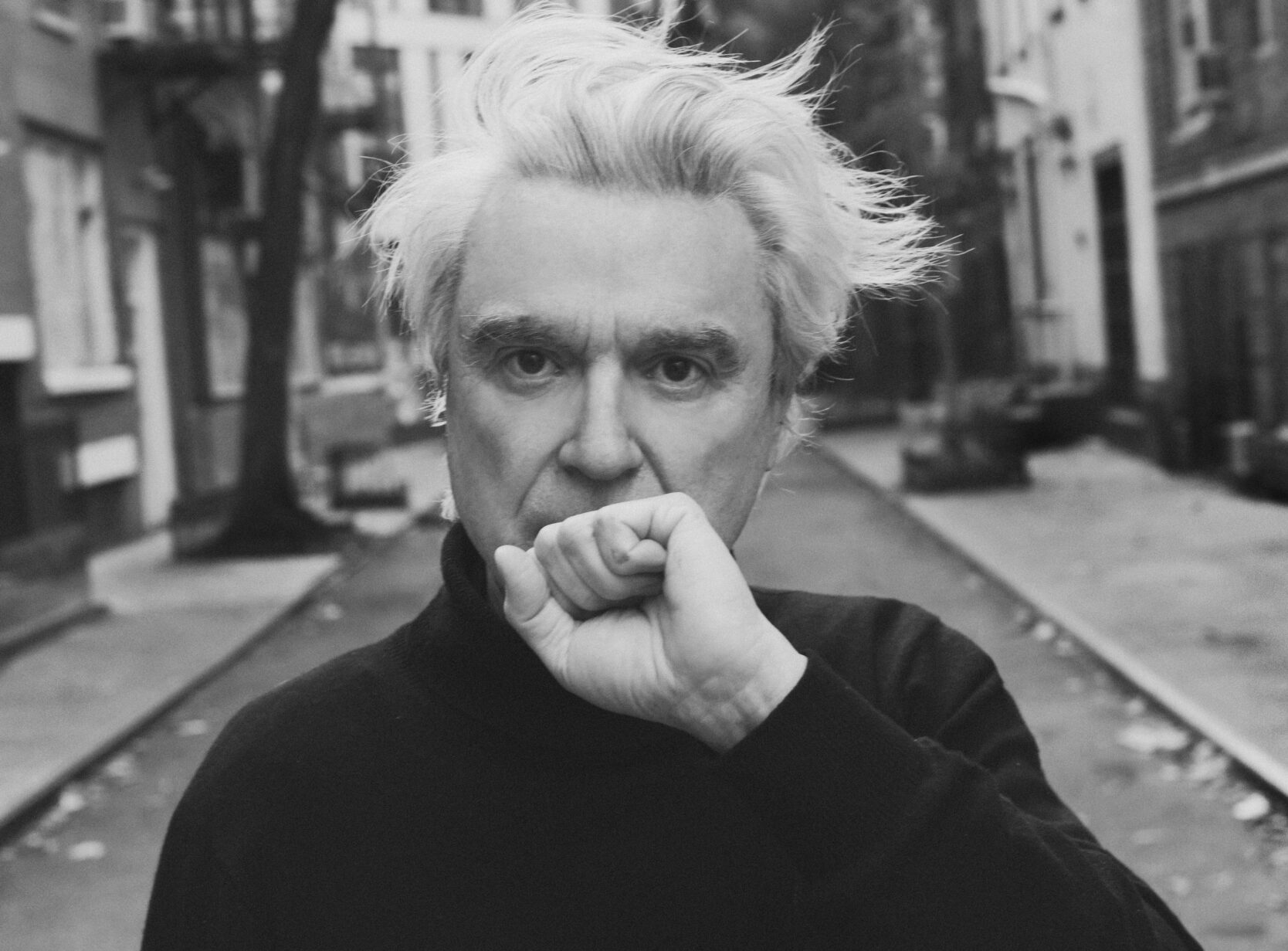

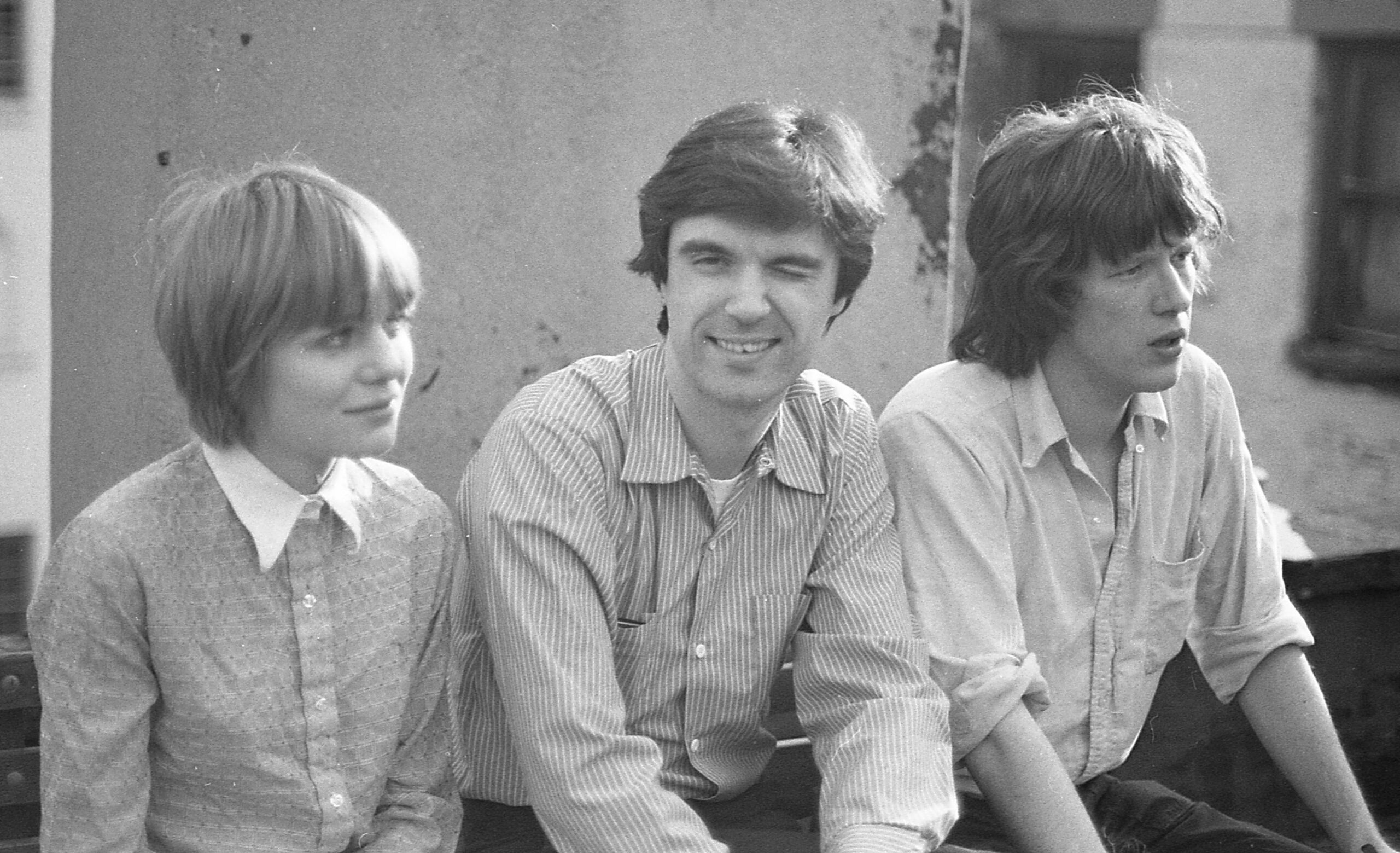

“True happiness, we are told,” Henry James wrote in one of his novels, “consists of getting out of oneself; but the point is not only to get out — you must stay out; and to stay out, you must have some absorbing errand,” which might be the most accurate way to describe David Byrne, whose exhilarating and surprising errands (his newest song is about a dystopian Santa Claus) have been celebrated in various artistic disciplines, and been celebrated for their originality. Byrne has been able to make his quirky sense of reality surprisingly popular.

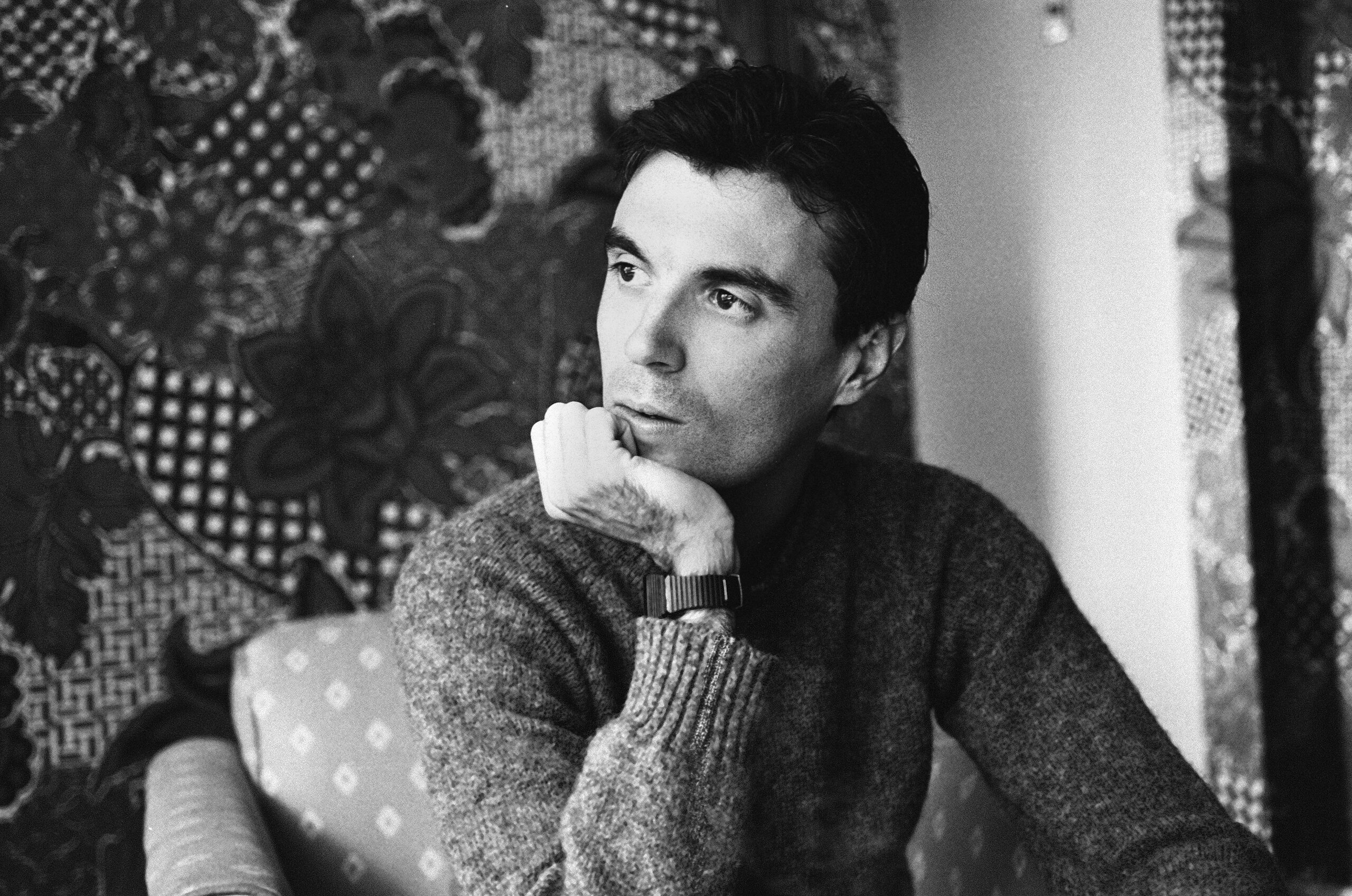

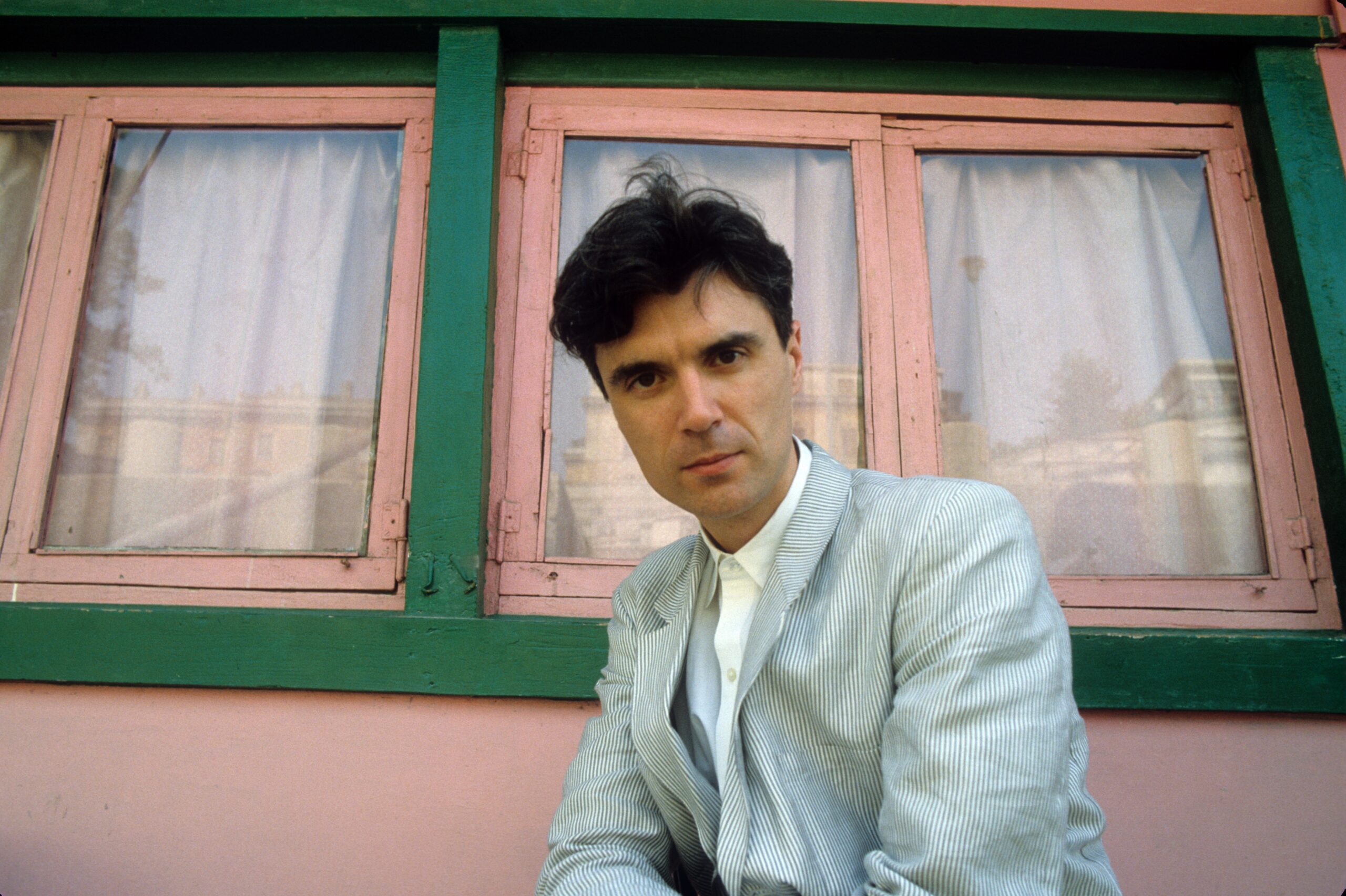

Most known, of course, for co-founding Talking Heads in 1976, the band broke up in 1991 — leaving him to pursue a wide range of writing and performing projects. In his bestselling book, How Music Works, he wrote that he has borderline Asperger’s Syndrome, which likely accounts for his lifelong awkwardness in social situations, and can be seen in his performances. As a result of being on the spectrum, Byrne calls himself “an anthropologist from Mars.” Fitting, I think, since much of his work comes from a peripatetic curiosity that leads him to discovering the inherent strangeness in what we think of as the everyday.

David Byrne’s other achievements include establishing two world music labels, Luaka Bop (1988) and Todo Mundo (2008), as well as creating the theatrical productions Here Lies Love (a collaboration with Fatboy Slim about Imelda Marcos), and the critically acclaimed phenomenon American Utopia, which critics have called the best live show of all time and “a hope for humanity.” The show had an extensive tour before its Broadway run and is now a film directed by Spike Lee. Byrne himself directed and wrote the film True Stories, and he collaborated with Ryuichi Sakamoto and Cong Su in composing the score for Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor, which won an Academy Award, a Grammy and a Golden Globe in 1988.

In 2019, Byrne launched a website called Reasons to Be Cheerful — billed as “tonic for these tumultuous times.” The platform consists of stories about people around the globe who have created projects that will make the world a more cheerful, sustainable place to live. The caveat for writers is to make sure the project is a success — not merely an idea. The site continues to be a respite and an oath that maybe things aren’t so bad as they might seem.

Byrne is also fascinated by science, particularly neuroscience, the study of the nervous system and the brain’s impact on behavior. In September, 2022, he premiered Theater of the Mind for the Denver Center for the Performing Arts (extended through January 2023), which has been described as an immersive theatrical experience. The audience is split into groups and taken through a series of rooms every 15 minutes, where scenes are staged to challenge each participant’s sense of reality, presented as an experiment in neuroscience research. “It’s all inside your head,” the press release assures us, “but is any of it real?”

Byrne’s publicist asked me not to dwell on anything nostalgic. Except for my lavishing praise on him for American Utopia, (I couldn’t resist), we talked about the right-now of his absorbing errands.

You just released a new song on Bandcamp called “The Fat Man’s Comin’” — a sort of funny and dark version of “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town.”

Well, I just looked at it literally. Here’s a guy that comes from the frozen wastes once a year. He dresses rather strangely. He slips in at night and breaks into people’s homes and leaves packages.

Unattended packages, as you point out.

Unattended packages, yes. So, those could be removed by the security folks.

What inspired you to write the song?

[Laughing] I have no idea, but once I got started, it was just, tell the story, make it literal — a large man wearing big leather boots and an oversized leather belt and a lot of fur around the collar and stuff like that. These are rather interesting sartorial choices. We never see this guy. He comes in from the frozen wastes at night and does his thing. And I thought, that is so bizarre. We just accept it as this charming thing and children sit on his lap without looking at what’s really going on.

For Theater of the Mind you draw on your own biography — is that a fair assumption?

Yes, parts of my life are in there. But while a lot of it might be believable as part of my life, it’s actually not. There’s a room where you go in and the actor says that he DJ’d in this room for months. I never DJ’d in my life, but it’s completely plausible that I could or would. And another room where the guy is working at a kind of CCTV surveillance job, where you have to watch monitors for signs of anything suspicious going on. I never had a job watching surveillance cameras.

According to your press release, Theater of the Mind was “inspired by historical and current neuroscience research and how we see and create our worlds.” What’s the relationship between neuroscience and making art?

Making art is a kind of investigation, a kind of exploration. You often don’t know where it’s going, it’s not exactly paint by numbers. You always make some false starts. We worked on the show in Denver for eight years, doing workshops. And we’d go in one direction and then we’d have to change it. The core stayed the same, but a lot of it evolved and changed. And I thought, that’s very similar to the way science works. In talking to the various scientists as we were working on the project, I discovered that they work in very much the same way that a musician or an artist works. Intuitively.

You have the website Reasons to Be Cheerful. I was so happy to see the world isn’t only this crippling sense of bad news.

We have writers and reporters all over the place. There’s one guy based in Paris, a guy in Nigeria, somebody in LA. They pitch stories and we go, that sounds good, but remember, you have to show evidence that whatever it is you’re reporting on has been successful, not just a good idea.

Was there one particular reason to be cheerful that stands out for you?

I remember talking to a group who did a study of misdemeanors, small crimes, crimes without violence — anything where the person wouldn’t automatically go to prison. They would still have a trial, but they wouldn’t go to prison. Whereas in some places, if you’ve done something and you’re guilty, you automatically get funneled into the prison system. And if it’s not a serious crime, it kind of ruins your life. You don’t have a chance to get back on your feet. It just makes life very, very hard. And, of course, the irony is that keeping people who haven’t done anything horrible out of the prison system is good for the economy, it’s good for the safety of communities. And it brings down crime in the future because a person isn’t coming out of the prison thinking of themselves as a hardened criminal.

I loved the voluntary gun law to prevent suicides, where people can sign up on a “don’t sell me a gun list.” If they wake up one day and decide to do themselves in and go to the gun store, the guy will say, “No, you’re on the list. I can’t sell you a gun.” An example of something counter-intuitive.

And a lot of times the people who are depressed, suicidal in that way, fall into the trough of the depression, and they will act. If they have a gun, they might act on it. But if they don’t have the gun, it can pass, and they might find a way out.

Do you think people will change to such an extent that we stop killing each other and the planet we’re living on?

I think a lot of things will change. I read Arundhati Roy’s article [about not carrying the past with us, and restoring rather than destroying]. I thought it was wonderful. It’s wonderful for us to extend this hopeful idea that tragedy could spur us to do what’s needed and change some of our assumptions.

Do we need a revolution to change things? When will politics, or laws, accurately reflect that we’re the owners of whatever happens to us?

I’m kind of hopeful that a couple of places I know — Michigan and some other states — are getting rid of gerrymandering, which kind of entrenches one political party and becomes really hard to dislodge because of the way that districts are defined, and that’s just not democratic. I don’t mean democratic in terms of party, but you can’t have a democracy when that kind of thing happens. Changes like this will go a long way in giving people a sense that they actually do have a voice. And some places are starting to adopt what’s called ranked voting. You vote for your top five candidates in order of preference. So, your number one choice may not win, but somebody else that you sort of feel is okay might get in. The effect of that could, in the long run, get rid of political parties, because political parties become irrelevant when you’re voting for different people. And if you’re registered as a Democrat or whatever, your third choice may be a Republican. You can cross the line. I think those kinds of things are healthy.

What are you reading at the moment?

I’m reading one political book, a book by Ezra Klein, called Why We’re Polarized. He goes back into history and comes up with some stuff that’s a little bit counter-intuitive and a little bit like, oh, I didn’t realize that. He talks about how people really stay locked into their party now, whereas, not too long ago, 30 years ago, people would vote for a Democratic senator and a Republican representative. They were crossing party lines depending on how they felt about things and how they felt about the person. That just does not happen anymore. And he says it’s really strange how dogmatic we’ve become about the tribal party.

You should start a pen pal project, where your pen pal is somebody who thinks and feels completely differently than you do, and you have to write to each other once a week. Isn’t that the problem? We’re not talking to people who don’t agree with us.

I know, I know. And I have to be honest, maybe it would be terrifying.

Any other books?

I’m also reading a book by Ed Yong called An Immense World. It’s about animal perception and he goes through all kinds of animals. It’s really incredible, like the way fish have these kind of magnetic lines down their sides so they can sense the movement of other fish near them and all these perceptual things that animals have that we just don’t have.

There’s a bird, apparently, in Australia that can fly but doesn’t because it doesn’t have any enemies.

Ha! That’s great. Why bother? Why make the effort?