Bob Guccione, Jr. needs little introduction to readers of SPIN, but for our interview (as part of the SPIN DNA series), we focused our conversation on the unique and controversial column on AIDS, “Words from the Front,” which ran in the magazine from 1987 to 1997.

The award-winning column dealt mostly with the disputes over and incongruencies of HIV as the cause of AIDS, and the deadliness of AZT, once the only sanctioned treatment. The column also probed overlooked, under-investigated possible contributors to the syndrome of diseases that made up AIDS, which the NIH didn’t want to deal with. SPIN consistently caught the government covering up what they didn’t know and, scandalously, some of the things they did know to be untrue or duplicitous but stuck with anyway.

It is not an exaggeration to say that SPIN led the rest of the world’s media in exposing the vast amount that was either wrong about early hypotheses of AIDS or simply not known. The column was the most read section of the magazine and regularly received the most letters of any editorial we published.

Bob is currently a consultant for SPIN and founder and editor of luxury travel site WONDERLUST.

SPIN: Tell us a little bit about Celia Farber, who did most of SPIN’s reporting on AIDS. Is it true that nobody at the magazine would read her first piece until she snuck into your office and put it on your desk?

Bob Guccione Jr: That was a recurring theme at the magazine, and I let people go for interfering with the column. There was a copy editor who started editing things, taking out unpopular opinions, and I fired him on the spot.

I was a first recipient of a GLAAD award, believe it or not. In their first year they made me Publisher of the Year for the AIDS coverage and taking up the mantle. We were the only magazine in the mainstream that would talk about it. Everybody covered it eventually, but the only people who were really delving into it and challenging the orthodox messaging was SPIN. And that was due to Celia Farber, absolutely. It was her column and her groundbreaking work.

At one point I also interviewed Peter Duesberg [the famous molecular biologist who contended HIV didn’t, at least alone, cause AIDS] who featured a lot in the column. Whether he was entirely right in all of the conclusions is a separate matter and should be kept separate. The most important thing is, as a scientist, he actually, earlier in his career, turned down his chance to get a Nobel Prize, because he thought he was wrong. This has never happened in Nobel Prize history where a scientist said, “Wait a minute, I know you’re about to give me this, but don’t because, actually, we’ve done some more work on it and we’re not right!” And his partners went ballistic, kicked him off the team, won the Nobel Prize, and were later proven to be wrong and Duesberg proven right. As a scientist, he did a great job of challenging issues; he was right on every challenge.

Now, his conclusions to this day are not proven one way or the other. What is proven, and this is something we adhered to throughout the 10 years we ran the column, is that there are incongruencies in the understanding of AIDS and its causes. The incongruences include there are people with AIDS who don’t have any presence of HIV; there were people with HIV who never developed AIDS—a lot of those, including infants who got HIV at birth and within six to 12 weeks had gotten rid of it. So if a baby’s immune system, which isn’t even formed properly, is incredibly weak, can defeat this virus, then it can’t be the all-conquering virus researchers declared it to be.

I thought Peter’s challenging of issues was very important. The incongruencies exposed were vital, and that’s what we built the column on, those incongruencies. And repeatedly, no one ever proved us wrong. I didn’t expect that we’d solve the AIDS crisis, only that we would repeatedly push the important questions.

Duesberg became ostracized as a result of his inconvenient questioning of the orthodoxy, because he didn’t realize what a multi-billion dollar industrial complex he was up against.

And of course, as always about stories that have controversy, this is about money. AZT was the most profitable drug ever to hit the market.

Of course it was because it had no research costs, it was a failed, shelved cancer drug, it was expensive and amazingly simple and easy to produce. I always said, we never once said HIV doesn’t cause AIDS. What we said was, we don’t think it’s been proven that it does. And that’s an important distinction.

But to get back to Celia Farber, she was an intern at SPIN. She was a kid, 19 years old, I think. She did xeroxing and we sent her to the library to find out things, sent her to record stores to find out names of records. But she’d written a little something for us, and I thought it was pretty good. The idea for the column, however, was from our art director, Amy Seissler. It first came up at a meeting and everybody in the room laughed, and I said, “Oh no, wait, that’s a brilliant idea.”

Why did they laugh? A straight music paper writing about AIDS?

Exactly—writing about death.

What else is there to write about? Why do we write in the first place?

Exactly right. In the interim, we’d left Penthouse and we started up separately again and Amy had gone by then, but I remembered her idea. Celia came to me with an article pitch. She said, “There’s something called AL 721 in Israel. It works and it subdues HIV and AIDS and people are getting better.” I said, “Well that’s a great story.” And she said, “Yeah, but nobody will run it in America. The FDA won’t allow it in America.” I said, “Great, do the story.” And it came in and it was very good and she was clearly a talent. Bob Keating was the editor at the time and he and I edited her copy and I said, “Well, let’s start the AIDS column.”

Now, de facto, it was her column because we published her piece. And then she tracked down Peter Duesberg and does this interview with him and it comes in and I don’t see it on any production schedule. “The AIDS column runs monthly, where is it?” And editors said there were problems with it, it’s not ready. And I said, “Well, get it ready.” And everybody backed down and it got to press. And there was tremendous controversy, people were up in arms at the magazine, and across America.

A lot of outrage from the gay community, correct?

Yes. At that moment there was a fascinating dichotomy of a community ostracized, minoritized, ghettoized, and generally disparaged, and underneath all of that, disliked, that suddenly was being felt sorry for and had become exotic and the darlings of the media and Washington DC’s inner circle, because they were harboring, in white mainstream America’s mind, a menacing virus.

Because men were having sex with each other?

That’s part of it—sex that white, conservative America didn’t want you to have. So, by 1985-1986, there were a number of people who are rushing to show their humanity and their largess by trying to help you, also being very fearful that it was coming for heterosexuals. So there was this moment when this suppressed community was suddenly right there on center stage, floodlit. You were in the news, feted by celebrities, and people wanted to help, and “we’ve got to stop AIDS!” And there was safe sex campaigns and everybody was part of that.

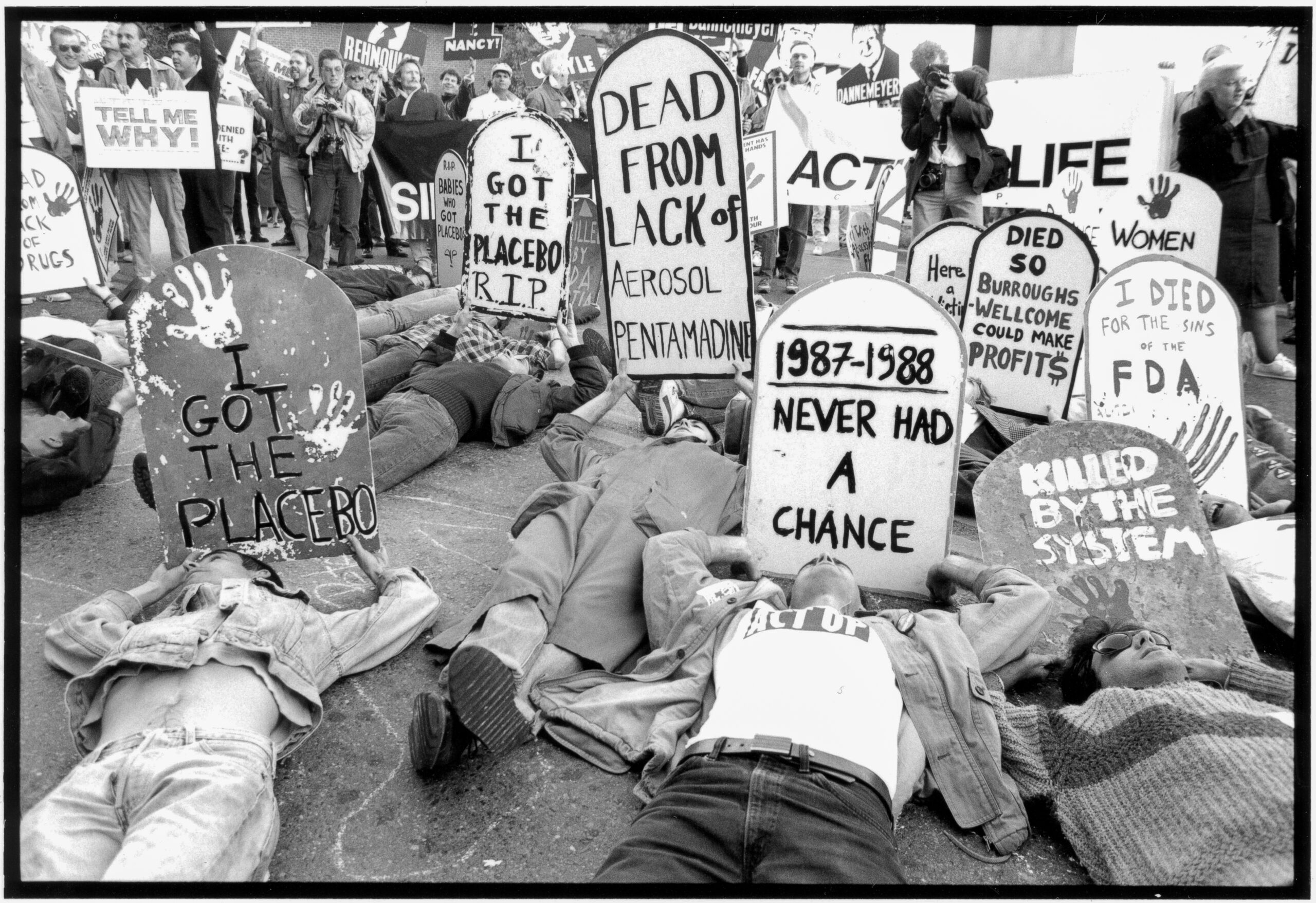

And ACT-UP, which was the voice of real activism.

ACT-UP was, in my opinion, intoxicated by their celebrity and so they were malleable. Along comes pharma and says, “oh, you poor people, let us help by giving you this drug and we won’t charge you a lot for it. And we’ll work with you and we’ll help you and you just tell everybody about it and we’ll make sure you get it.” And that was AZT, which killed faster than AIDS, as we reported. And eventually, because of our reporting, AZT went away and people lived longer.

Do you really believe it was your reporting?

Absolutely. Oh, no doubt, because we were the only ones doing it and everybody said “SPIN says this, SPIN is reporting that” because they didn’t want to touch it with a bargepole! So when it became obvious, other news outlets picked up on it and some started copying our columns, like the UK Sunday Times, and then doing their own reporting. We literally changed the way the media reported on AIDS.

ACT-UP was single-handedly responsible for lowering the price on AZT by thousands of dollars a year. They had a mission and they really accomplished it.

You’re right, but let me go back to that moment, that sort of perfect storm of political correctness. Because now you have a group that is being lionized and throwing concerts and Elton John is their patron and Mathilde Krim [from AMFAR] is their little godmother, another disparate character who really didn’t know what she was talking about, by the way. All of this glamor and glory is coming to these resistance fighters and they are leading the lambs to the slaughter—unintentionally, obviously. But they weren’t challenging the government’s orthodox opinion because it worked for them.

The importance of the column was that we raised questions. And then we interviewed [Robert] Gallo, but we were very wise to the fact that he’d stolen the virus sample from [French researcher] Montagnier, which we brought into the light. That became a national scandal. We were getting these fantastic stories, fantastic interviews and doing fantastic research.

And, again, some of the editors didn’t like the column and I said, “We run this. If you don’t like this, you don’t work here.”

Was it homophobia? What didn’t they like about the column?

It was really that early dawn of political correctness. It was people who didn’t want to be looked at as being crazy. It was much safer to go with what you were reading in Newsweek and Time and seeing on the news than it was to be punky little SPIN on 18th Street in Manhattan turning out a magazine that said the government was wrong and knows it.

Which it should be, no? That’s the publication it professes to be, I would think.

Absolutely. It picked up momentum and we shed the early naysayers, or they shut up. I finally edited every column myself because I knew we had real journalism and I knew it was important. It was more important than anything we were doing musically. It was the most read part of the magazine. The year before I sold SPIN I thought, after 10 years, maybe the AIDS column had run its course, and we should cut back to an occasional article. And because we work a few months ahead, there were issues after I sold it that included the column. But as soon as the new owners had the chance, they dumped it; they didn’t want it. The new owners just wanted it to be a music magazine, and that’s when it started to fall off a cliff.

The AIDS column was a natural because 100% of our audience was having sex; everyone was very worried about AIDS. We did this great, landscape-changing reporting and it had its life. It’s an untold story that there was such internal resistance, which is a shame because it was such monumental work.

You once said in another interview that you considered AIDS the Vietnam of the SPIN generation, our generation, actually. What do you think is the Vietnam of this generation?

Vietnam preoccupied my generation and the draft ended a month before I could have gone in 1973. But my generation went or had to go or had to not go. So we were preoccupied with that as life-changing, out of our control. And I thought AIDS was the same thing in their generation—a life-changing, out of their control condition, about which very little truly was known. And there was a lot of obfuscation for it. I think the worst years of AIDS lasted about as long as the Vietnam war, too, give or take.

What is the Vietnam of today? Well, that’s a complex question, because there’s not one central definable force that we see on the horizon and are putting up barricades against or fighting. We have a much more diffuse horizon today. I would say, clearly, the Great American Divide politically is a problem. The very real disintegration of respect for the Constitution and respect for civil life and the devaluing of what is empirically true is a problem, too.

We’re living in Wonderland, a completely altered reality.

When I was a kid, it was popular to say the moon landing was a hoax. What proof do you need? You need to be taken to the moon to go see the American flag standing there? There are still people who think the Holocaust never happened. Why don’t we just say the Normans didn’t invade England, or the Vikings didn’t come to Greenland. There’s a certain point we can’t prove anything beyond the mountain range of proof that is offered. I always say, a mountain always fails to go one inch higher. You can always be unimpressed with the mountain range of proof to make it untrue. We live in an era where people are literally just inventing whatever scenario they want. We’re living in an era where people are inventing characters and situations as they would have in [virtual community] Second Life.

I wonder if that has something to do with having a virtual reality or a virtual persona.

I don’t think so. I think that the people who are having this virtual reality are not smart enough to understand virtual reality. They’re having an adult alternative reality.

Yes, but if the nature of truth in virtual reality is somewhat parallel to the nature of truth for people who don’t live in virtual reality, where is the bar sitting on what’s true?

I think virtual reality is a very complex technological achievement that simulates real world motion and we can play with it and create things that don’t happen in the real world. But the real world obsession with alternate reality is dangerous because it has nothing to do with being in a game or a scientific experiment. It has everything to do with destroying the fabric and the fascia of social existence. And that’s very different and very consequential. What happens in virtual reality is not consequential. You can hit a golf ball for 800 yards, great, who cares? Nothing changed. But in real life when people create these avatars of Trump as the immortal guardian of the universe—which he is in some people’s minds—one could ask, well, with that reasoning, why isn’t George Washington your president?

It all feels like that great Peter Sellers movie Being There. From nothing, he creates something nobody can explain as truth or otherwise, which sort of leads me tangentially to spirituality and how you engage in that particular reality?

I’m a Catholic and I wouldn’t say I’m a good Catholic. I used to be, but I do believe in it completely. But I also believe in not imposing what I think to be true about the existence of life and the universe on anyone, and that religion is somewhat like karate. I used to say, well, I like my protocol, which is basically Goju, but it’s ridiculous to think it’s the only karate protocol, or the best, or only I have the answers when there are so many other martial arts that people are equally devoted to. And I feel that way about religion. God’s too good a businessman to only have 25% market share. There’s a lot of God, not a lot of Gods. But every person’s God, I think, is part of the whole.