It was a different time. Back in the day, any Berkeley student with a half-decent fake ID could stroll down University Avenue to go check out Bob Marley and the Wailers, with maybe a hundred or so other curiosity-seekers. Bruce Springsteen and his E Street Band played the same stale-beer-smelling joint, but to fewer paying customers, drawing less than Jonathan Richman’s Modern Lovers. A block or so away was a club where Lightnin’ Hopkins and B.B. King and Muddy Waters all gigged, and Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman too, where Thelonious Monk did a week-long residency. A decade or so later, the most notorious dorm in campus history used to host X and Black Flag and the Dead Kennedys. And if your timing was right and you were a big spender flush with cash, you could do New Year’s Eve with the Red Hot Chili Peppers, but it was terribly pricey: Twenty-five bucks at the door, Buster, with chili and champagne included.

You know what else you missed? You missed seeing Charles Brown playing Larry Blake’s basement. Can you believe it? Here was the most urbane blues piano player on the West Coast of the Whole Universe, an essential artist in the history of rhythm & blues, the original master of club blues… and we could easily have just strolled over to Telegraph and Durant on a chilly evening and heard Charles Brown sing “Merry Christmas, Baby.” Dang! What were we thinking?

First, to salt the wound, you’ll want to play Mr. Brown’s original “Merry Christmas, Baby,” a song that’s been covered by Elvis, Christina Aguilera, Mae West, Billy Idol, The Monkees, Booker T & the M.G.’s, and CeeLo Green accompanied by Rod Stewart with Trombone Shorty, among a hundred more. (But wait! Here’s a list as long as your arm, yet probably not even definitive, since the Christmas recording season is still upon us.

Charles Brown co-wrote “Merry Christmas, Baby,” sang and played piano on the tune with Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers, watched it become a hit and then – did you hear this part coming? – got perfectly aced out of the publishing royalties. ‘Twas ever thus in R&B, after all, and at least some of the other huge hits he wrote and recorded, like “Driftin’ Blues,” “Trouble Blues,” “Black Night,” and “Please Come Home For Christmas,” ended up helping him contribute to his favorite charity, those poor lost wandering ponies who placed out of the money at California’s racetracks.

He lived his later years at Berkeley’s Harriet Tubman Terrace, which made it all the more handy for him to hop a bus and visit the hustlin’ horses at nearby Golden Gate Fields. And it meant, too, that that long-lived off-campus bar Larry Blake’s Rathskeller, which became a bit of a blues mecca during the 1980s, was an awfully convenient place to warm up the third act of his career. There were a lot of older black blues folk who lived in Oakland and San Francisco’s East Bay. On a good Monday night at Blake’s, you might be standing next to Lowell (“Reconsider Baby”) Fulson, or Lloyd (“After Hours”) Glenn, or Jimmy (“The Walk”) McCracklin, or Sugar Pie (“Slip-In Mules”) DeSanto, waiting to sit in with the younger bad-ass white boys who kept the little bandstand lit. But Charles Brown… well, Charles Brown was different.

Originally from East Texas (from Texas City, Texas, no less), he earned his degree in Chemistry from Prairie View A&M, a Negro college, attending on a scholarship. That degree earned him a job in an Arkansas mustard gas factory, before he transferred to Richmond, California during World War II. Raised in church by his grandmother, trained as a classical player, Charles played Debussy at home with a loving, light-fingered finesse; the California blues of Charles Brown were, like Debussy, drifting — drifting like a ship out on the sea.

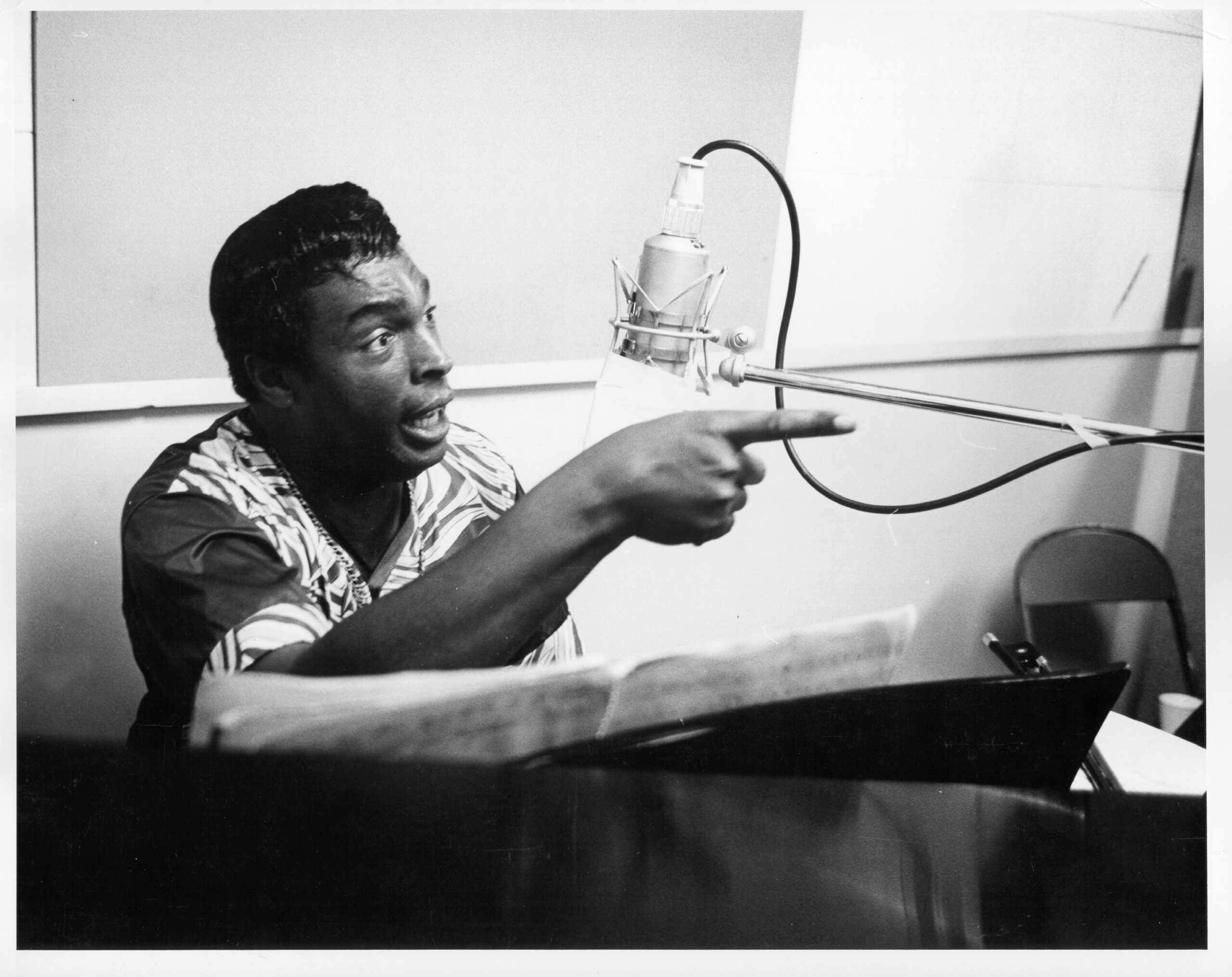

Even with all the talent packed in the little basement, there was nobody at Blake’s who’d been as big as Charles Brown, who’d sold more records, had played bigger rooms for more money, been as famous as Charles Brown. (Well, not until Bonnie Raitt showed up, anyway.) Ray Charles had based his early work on mixing Charles Brown with Nat “King” Cole, and everybody black and white had covered his tunes. “I was the Michael Jackson of the Forties,” he’d sometimes say, but no matter. Now he was at Larry Blake’s, down in the cramped little basement down under the restaurant clatter, looking every bit as good as he sounded.

“Charles Brown was the nicest man I ever knew.” Harold Jones is Tony Bennett’s drummer these days, after years swinging with Count Basie (“Basie gave me the best tip I ever got: ‘Stay away from those horses.’”) and back in those days Jones’ mainstay gig was behind the impeccably sassy Sarah Vaughn. He didn’t take blues gigs customarily, but he loved playing with Charles, so here he was in Blake’s basement. Clifford Solomon, Ray Charles’ musical director, was here too, playing just enough sax to hurt you, and Ruth Davies on double-bass and Danny Caron comping on an archtop f-hole Gibson, all looking clean, lean, and serene in tuxedos — even Ruth. But Charles’ own tux, the flash one with the silver embroidery everywhere, shining in the spotlight, light glinting off the silver medallion on his yacht cap, and that big right hand diamond pinky-ring – but wait! Shhhh! They’re just commencing “Please Come Home For Christmas” — where else in the world would we want to be for the holiday?