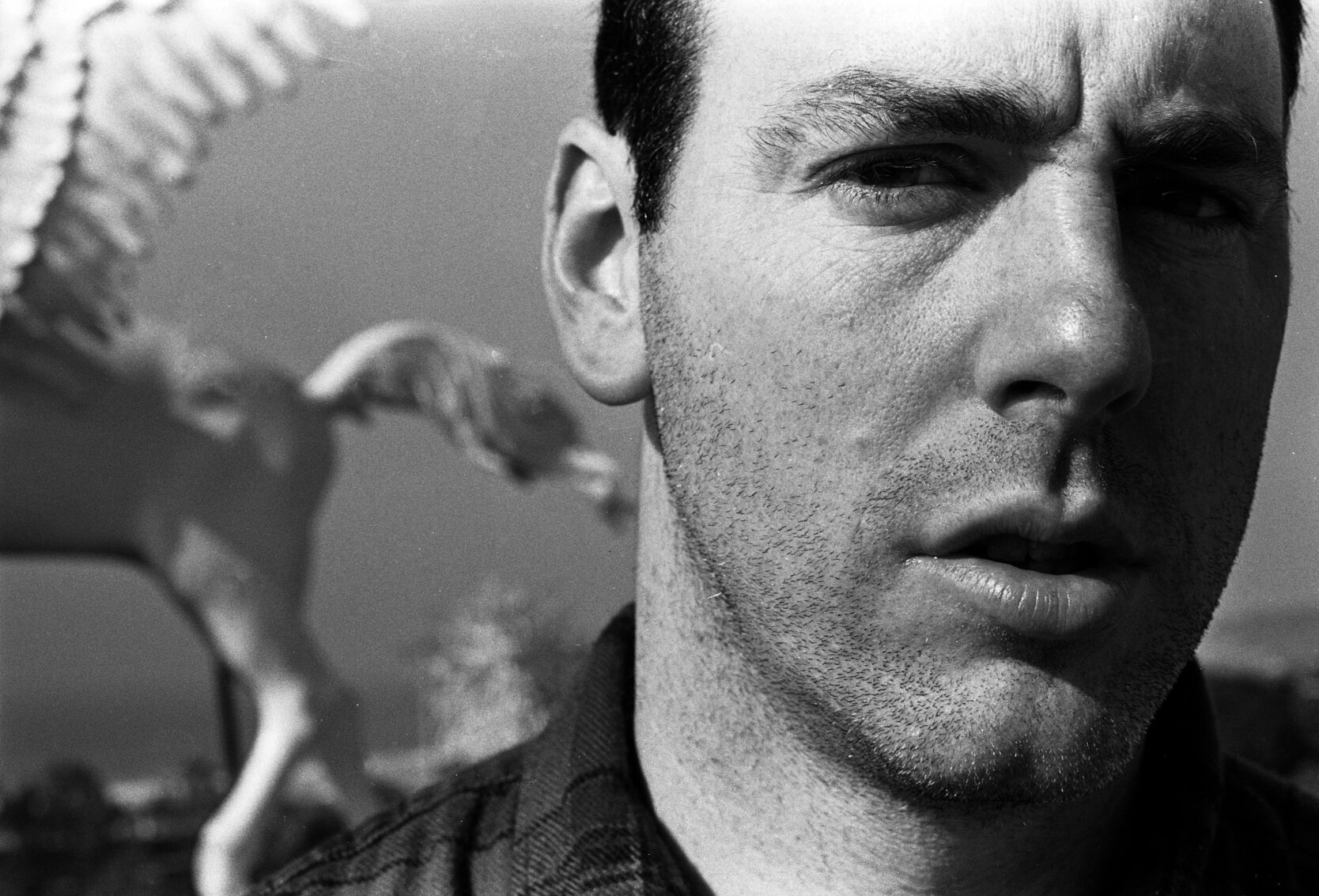

Greg Graffin enjoys the balancing act. He thrives in the reconciliation of two worlds that he cares about deeply: punk rock and science.

“It’s a ping-pong match,” Graffin, Bad Religion co-founder and lead vocalist, explains. “Sometimes I’m on one side of the net, and sometimes I’m too far on the other side of the net. But yeah, it is a constant back and forth, and it does make me tired sometimes, but it’s very rewarding when it works.”

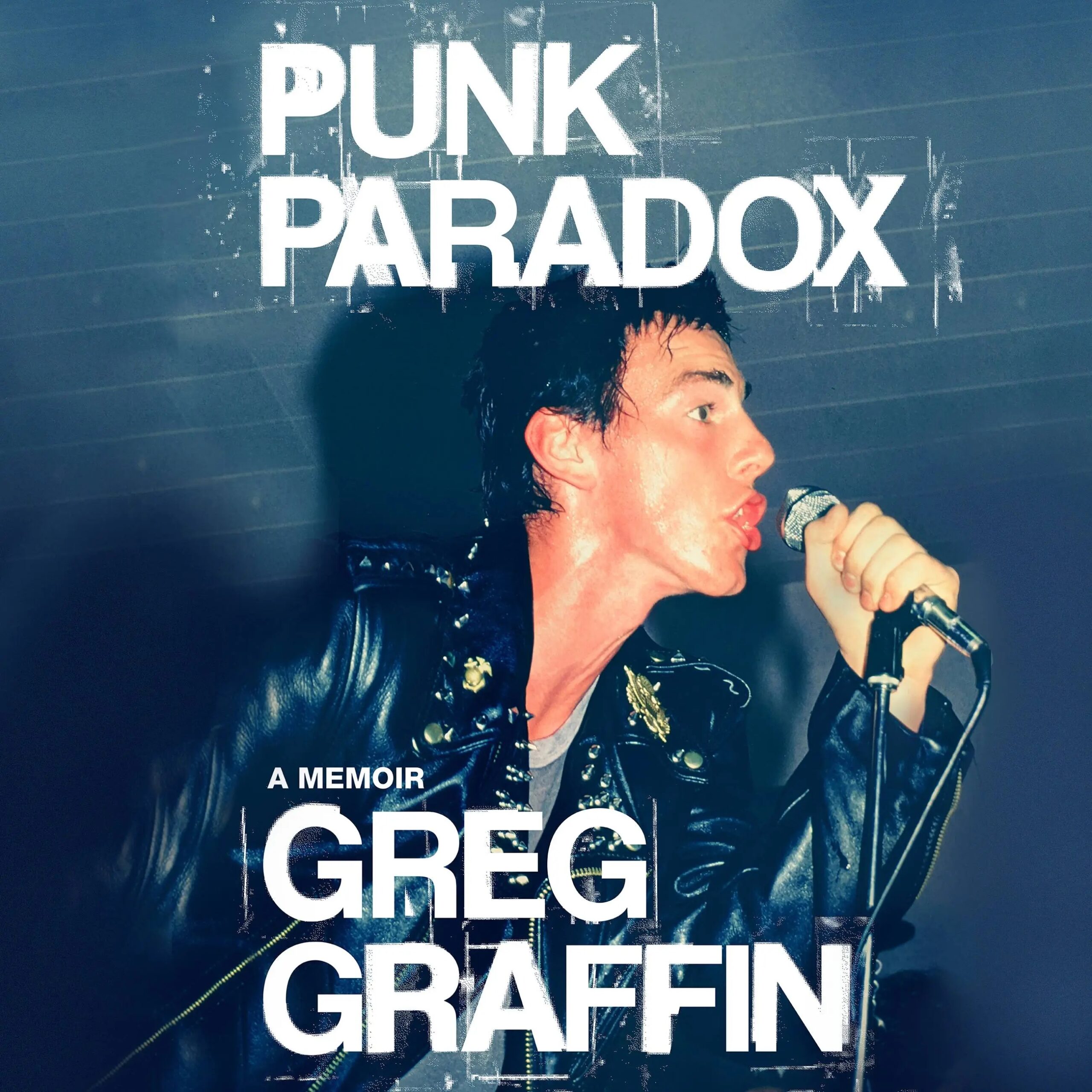

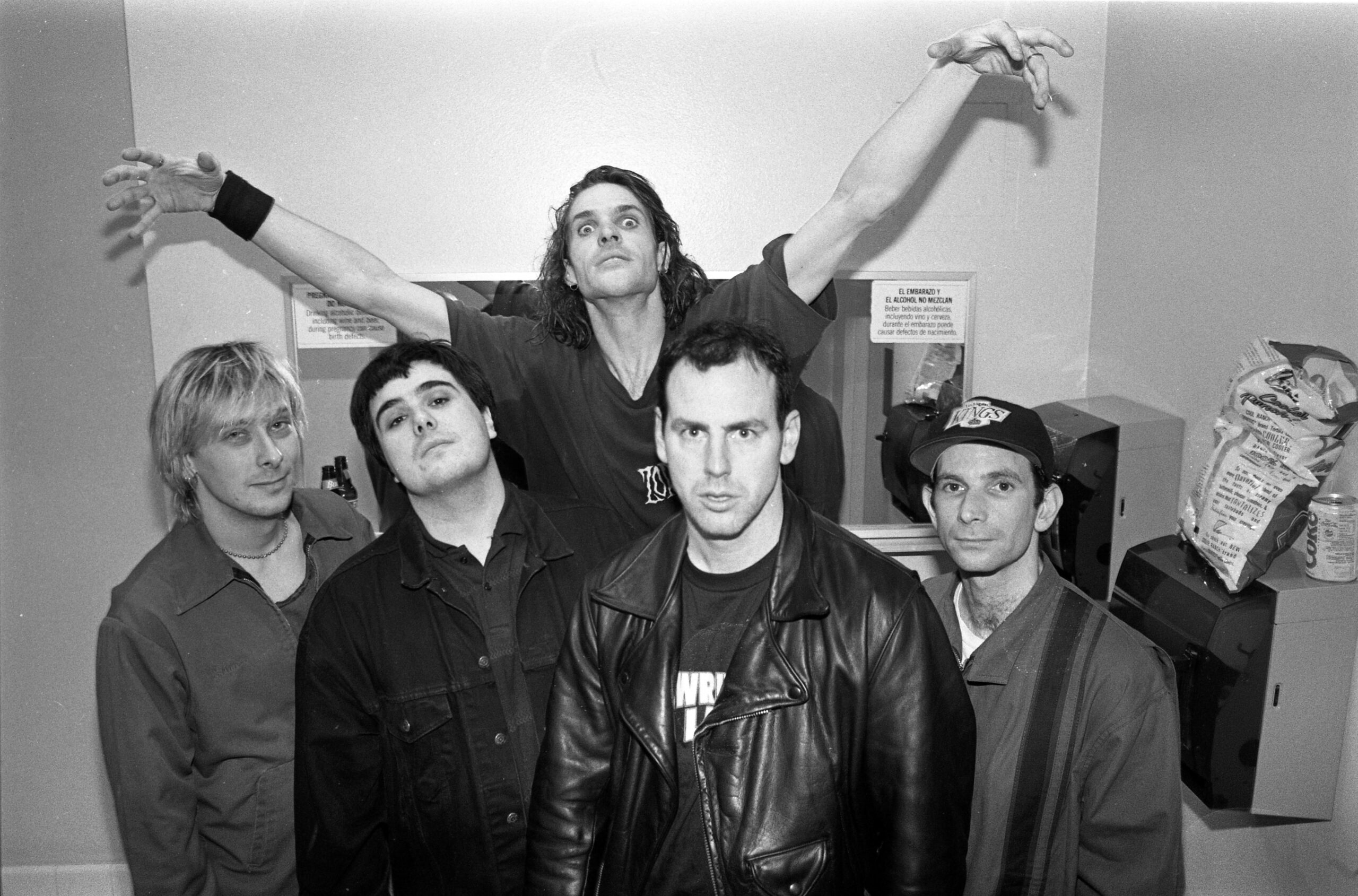

This net has become increasingly, undeniably wider as Bad Religion has restlessly and relentlessly continued to impact punk music and culture around the world for more than 40 years and 17 albums — not including their Christmas record (2013’s Christmas Songs), which may pleasantly surprise you this holiday season. Graffin’s new memoir, Punk Paradox, documents the endless trials and tribulations, as well as the colorful characters who come along with it, all taking place on the allegorical campus of Graffin U.

Rather than focusing on elements like the now-iconic crossbuster logo or major moments in the band’s rich musical canon, Punk Paradox tells a compelling — and sometimes turbulent — tale of an artist and academic’s pursuit for understanding and (dare I say?) enlightenment. At a glance, evolutionary biology and L.A. punk rock may not appear to have many similarities. However, thanks to Graffin’s charismatic prose and enthusiastic storytelling, the parallels are more obvious than one would think. The research scientist in Graffin meticulously documents the many pertinent details and data in his personal story, while the artist weaves this swirling mass of information into a language and style that only he, with such an incredibly unique background, could communicate. From his home in the “desert regions of California,” Graffin spoke to SPIN about excavating painful memories for his third book.

SPIN: Right off the bat, I was impressed with how much detail, for so many memories and observations, are captured in the book. How did you do it?

Greg Graffin: That’s a good question, and it’s kind of an insightful question because you noticed the detail, but the idea that to note detail requires research is sometimes inaccurate. I keep saying that it’s a literary memoir, and what does that mean? I wanted to borrow some of the techniques of novelists and techniques of non-fiction to make a story, and part of that is the detail. If you read a good novel, it’s full of details and it really paints a picture.

I think I’m just very fortunate that I have a very sensual memory…I don’t always remember the details in perfect chronological order, but I remember the tastes, the sights, the smells, the sounds of experiences in life. That therein leads to the observation that all storytellers will remind you is that memory is fallible – it’s never meant to be perfect. It also gives me an out when people get pissed off I got the chronology wrong. (Laughs.)

There are so many interesting tidbits in this book, some quite funny but also some that are quite sad and tough to read, like when your family moved out of the house. Was it hard revisiting those hard memories?

Oh yeah, but the vulnerability of writing about people and events is rewarding as well. It’s stuff I think is important to the story and I think other people can relate to it. When you decide to write a story, details or not, you’re always asking yourself, as a writer, is this something the reader is going to enjoy? Is this something that can connect to the reader? Otherwise, it’s just a self-congratulatory piece of shit. (Laughs.) I really did it with care in mind, and I cared about how it affected the storyline. And as you probably noticed, it was very important to my later path in life, the trajectory we took as a family.

Throughout this process of going through your personal history, what did you learn most about yourself?

The book is an exploitation of what I’ve learned about myself. It’s not perfect, but it’s a work in progress; it’s all in the interest of trying to fulfill the dictates of the expectations that were put upon me in the culture of the family — and how that conflicted with the expectations that were put upon me in the culture of punk. So the whole thing is a process of learning and by doing and by trying to fit in. That’s probably the part that, if people read it carefully — or read it twice — that they will recognize that there’s a lot of dissonance in there. “Know thyself”: That’s the ultimate academic exercise.

I love the photo used for the book cover. Do you remember where and when it was taken?

You know what’s amazing? You won’t see that picture anywhere…it’s literally a rare find. You can find pictures of the olden days everywhere, early punk and Bad Religion pictures, but this one came out of nowhere. It was taken by my friends who did a weekly photographic poster called Fer Youz. Fer Youz would go and hand out these posters at the shows, and I guess they had an art exhibit in L.A., not too long ago, and this print materialized from their archives. They documented that it was at The Barn, which was this kind of warehouse in Southern California on the night we played with the Dead Kennedys.

So I do know where it was, but to answer your question about if I remember it, I do not remember it because that pose that I’m taking could have been any gig in the early days. And of course what I’m wearing could have been any show also because I always wore that same leather jacket.

Where is that jacket, by the way?

It’s hanging in my closet, and now my little eight-year-old boy loves to dress up and put it on all the time. It’s become part of the family wardrobe.

Is it true that Jesus Christ Superstar was your most influential album as a kid?

Oh, it’s incredibly influential. I think I detailed some of the reasons [in the book], but I could go on for how influential that album is; it just fits into the entire story. I was never raised with the Bible; I never knew anything about religion. I loved music, and then this thing comes on because my mom bought the album and I listened to it day and night. If you wanted to learn the songs, you had to learn the lyrics, and if you learned the lyrics, you don’t know what they fuck they’re referring to when you’re that young, but you learn them and slowly the story comes into focus. So it’s a story of the Bible, but what is the Bible except a guy who struggles against the currently held view of the Roman empire?

The way it’s presented, by Andrew Lloyd Webber, is that this guy was the first punk. He’s just a punker trying to make a point against an army of cultural precedent that was in place for a thousand years before he came along. He is casting this story as the true outsider, so that was very appealing to me, even before I was a punk rocker. I was really drawn to this story, this individual — who is a great singer, by the way — and he had a philosophy that was in contradistinction to the currently held view. I can’t overstate how influential that album was.

And Charles Darwin seems to be another kindred punk rock spirit who you discovered early on as well.

Yeah, later in high school when I started reading about evolution, Darwin was also to me, an outsider who made discoveries and of course was afraid to publish them because they were going to revolutionize the way that the establishment viewed nature. It took him 20 years to publish it, his discovery of natural selection, and another 50 or 60 years after that before it was accepted. It jibed nicely with the punk ethos — the kind of punk I was interested — which, as I say in the book, is a rebellion of the mind and a rebellion of a show of force or some kind of violent tendency.

What’s your experience been like watching punk go through some pretty big motions over the years?

I’m not the best person to ask that because, for instance, when I write a new song, I don’t really think about what’s popular right now; I don’t think about ‘Is this going to be a hit song?’ or ‘How is this going to reflect in the new music that’s out there?’ It’s got to be personally motivating and come from the heart. Because of that, I’m not a good gauge. Even though I’ve always been a songwriter and I love music and I love listening to music. In Bad Religion, I consider myself sort of a content creator, and because of that I’m not a very good marketing person, so I don’t strategize.

I just think that a long view of the genre will prove, if you want to analyze it, that punk is a resilient art form and it’s had many kinds of ebbs and flows, and it’s gone in directions nobody could have predicted, and that has not destroyed my desire, one bit, to continue making contributions to it.

How do you want to be known down the road: as the ever-questioning songwriter for Bad Religion or as a challenging evolutionary biologist who pushed the field’s boundaries?

This question centers on a supposition. The supposition is that I care about the future and what people will think about me. I don’t really care. (Laughs.) When it comes down to it, what I care about is how my family thinks of me…their opinion of me is the only thing that matters. In my work, I would say I care about the people who are fans.

As I say in the book, you have to write with some degree of understanding of what they want. I think that if I can make a personally satisfying piece of art — be it music or written work — if I can make something that’s truly satisfying, then I’m pretty confident I will fulfill my goals for them. But it’s ultimately up to them to decide if I’m forgotten. That’s okay, too.