In addition to being a celebrated film critic (including, back in the day, at SPIN) and historian, Elvis Mitchell recently added “documentary filmmaker” to his resumé with Is That Black Enough for You?!?, which hit Netflix on November 11th.

The film is a deeply personal and passionately researched survey of the African American contribution to movies, from the earliest archives to culminating with a deep dive into the 1970’s, long considered the quintessential period for Black filmmaking. But Is That Black Enough for You?!? also critically looks at Hollywood’s preoccupation with shaping a culture rather than responding to that culture.

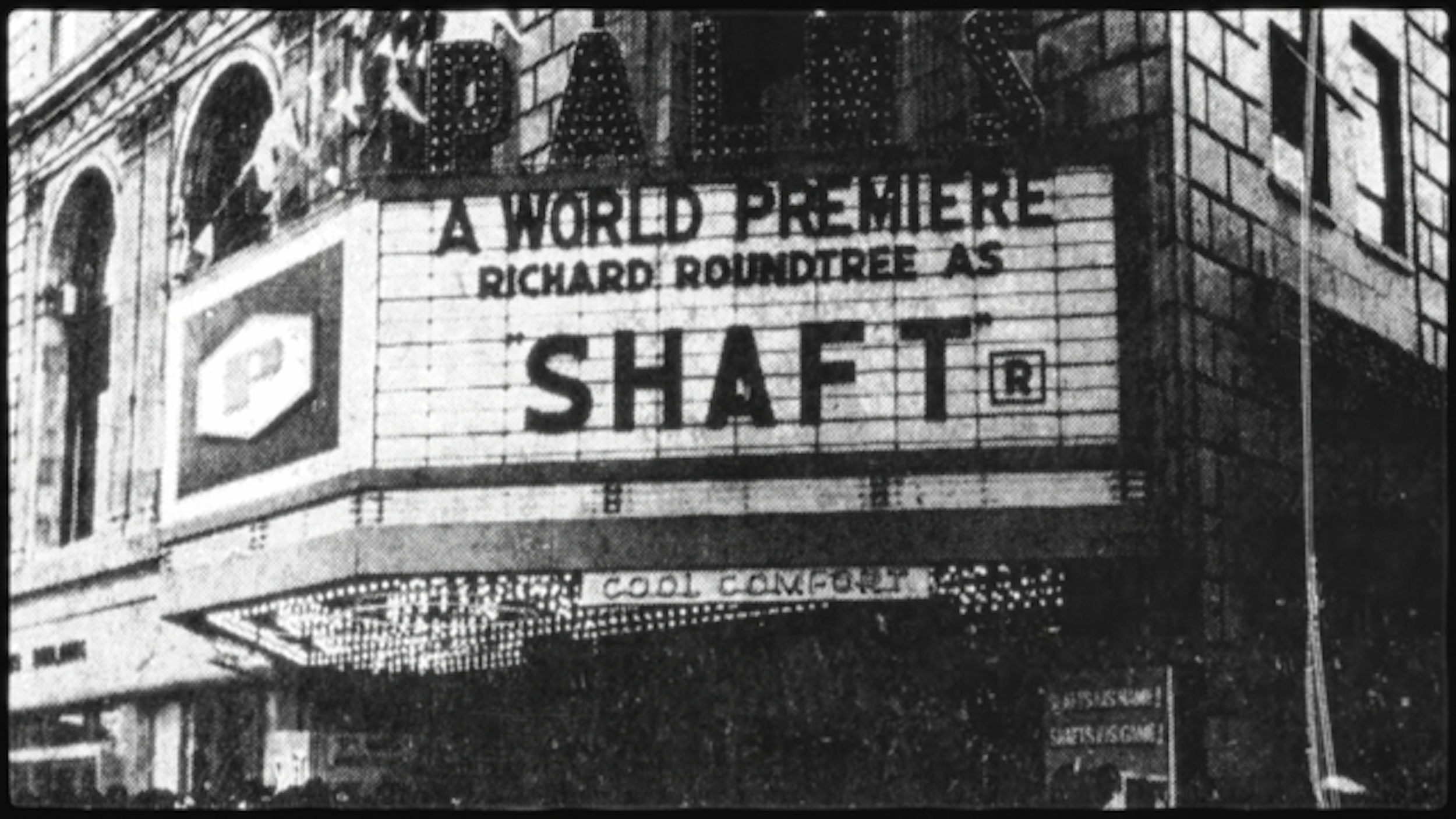

With the participation of actors Samuel L. Jackson, Laurence Fishburne, Whoopi Goldberg, and others, the documentary serves as a discussion on race, inclusion, Hollywood, and the commodification, or blaxploitation, of Black culture in films like Shaft and Mandingo — movies originally targeted for release in Black urban neighborhoods. And the doc covers the tremendous influence that soundtracks from Black films had.

Elvis Mitchell is the host of KCRW’s nationally syndicated pop culture and entertainment show/podcast The Treatment and has been the film critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram (where he received the 1999 AASFE award for criticism), the New York Times, LA Weekly, and the Detroit Free Press. Before all that, in addition to his glory years as editor-at-large at SPIN, he was special correspondent for Interview magazine. He’s always been a silky writer, a brilliant critic, and an erudite observer of life.

We caught up with Elvis Mitchell in New York.

SPIN: One of the many things that I loved about your documentary was how it can be seen as memoir. You’ve said you first saw it as a book and Toni Morrison was going to write the introduction. What was the transition to something purely cinematic?

Elvis Mitchell: I think the documentary is still what it is in literature.

When I was a kid, I read The Devil Finds Work by James Baldwin, which is a huge influence on me. When I was in Detroit in the early ’80’s, managing and working as a projectionist at a movie theater, I saw this guy walk past and thought, ‘That’s James Baldwin, but there’s no way in the world he’d be in downtown Detroit.’ But he was there, to give a speech at a library that wasn’t far from the movie theater. So I invited him to watch our double feature of Arthur and Alligator and later got a chance to talk to him about The Devil Finds Work. For me, it’s his most profoundly affecting writing. You can feel how his nerve endings are exposed without that kind of martial impulse he has in other work to wrestle the subject into submission. You can feel his being lost in movies and not being able to shape them in a way he is able to impose his will on other idioms. And that’s how that power exists for me.

I’m crazy about The Devil Finds Work and how he looks at movies and actors. He writes, “Sylvia Sidney was the only American film actress who reminded me of a colored girl or woman, which is to say that she was the only American film actress who reminded me of reality.”

He also talks about the resemblance between Bette Davis and himself and how Bette Davis’s eyes remind him of his own eyes.

Which speaks, I think, to his queerness, as well.

Definitely. And Davis just seems to have a special kind of second sight that other movie actors did not — susceptible to all the vibes in the world, the sense of empathy that Baldwin got from her. That book really is responsible for my perspective and aesthetic and approach to looking at movies.

What was it like to work with Steven Soderbergh and David Fincher?

The great thing was them telling me not to be afraid of “the movie moments” — to be able to talk about, for instance, Dracula, and going from that to watching Eddie “Rochester” Anderson playing the Black version, or the way Black actors were allowed to play it — to ridicule fear.

There’s a palpable excitement when you delve into the connection between music and movies and how soundtracks by Isaac Hayes and Curtis Mayfield were released before the movies were, as a way to get Black audiences into the theater — another way of showing that Black films were made to shape the culture, not respond to it.

The studios are basically always trying to shape the culture, rather than listening to it — which would be a more honest thing to do. By saying that there were white picket fences, and Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney would go out and throw a show together, created this fear of anything that wasn’t of an experience — which wasn’t even representative of their own experience. Hollywood was creating a myth about what the American ideal was. And that notion of America got exported around the world. And one of those unfortunate repercussions was the way people of color, any marginalized society, was viewed in those movies, which is to say, not at all or in the most insulting ways possible.

You think about the way Native Americans were treated in the movies. Think about the way Latinx culture is treated and that clip I have in the movie of Paul Muni as Benito Juarez. In his book Five Came Back, Mark Harris talks about the Department of War and how they would look at Hollywood and go, “Even we’re not that racist,” and then suggest that there be more integration in movies than there was — an astonishing note to make.

There has been, until recently, a conspicuous exclusion of Black people, for instance, in horror movies, which I think is why Jordan Peele’s movies have such extraordinary appeal.

It’s not like we’re being excluded from horror — we’ve excluded ourselves. If you are thinking critically when looking at a movie, you are asking yourself what is not there, what has not been said. And there’s a reason for that, which is institutional racism. Then you ask yourself, well, why is this happening? Oh, it’s because we’re smart enough to leave the monster or the haunted house. So it becomes a way to sort of deal with that. But also, there are real life horrors that are worse than anything that could ever be seen in a horror movie, about day-to-day Black existence.

The horrors visited upon the flesh in Mandingo, which led to Robert Mapplethorpe’s sensibility in his photographs of Black men, by the way, is unapologetic about gothic sexuality and fear and resentment and anger and excitement — all those things that inexorably sort of splash onto each other. Once you start that rush of one, you can’t stop all the others from happening, too. It’s a kind of a penny dreadful storytelling that goes back to the beginning of slavery — this idea of ascribing these monstrous and also attractive traits under this thing that you don’t want to touch, but you can’t keep your eyes off of.

“Justifiable paranoia,” you call it, “is the scientific term for African American.”

It’s something I allude to when I talk about Melvin Van Peebles’ Watermelon Man. During the pandemic, people understood the concept of being gripped by fear when you step outside of your home, which is not something there would be any empathy for before the pandemic. I think that’s what made the George Floyd case so inescapable for the entire country — that people had never experienced having that kind of abject loss of power in just leaving their home. Oh, that’s what it’s like, oh, now I get it. Now I know what it’s like to have a paranoiac streak.

“A Black man with a mop or a tray or a broom in his hand can go damn anywhere in this country and a smiling Black man is invisible.” That pretty much says it all, right?

Yes, a great quote from The Spook Who Sat by the Door. That was one of those lines that when I saw that movie as a kid, the entire theater erupted into applause. They should have built in 30 seconds of silence.

It describes the trajectory from being in servitude to being in a body of joy, the smiling Black man. I love the part where you notice the utter joy so apparent in Black faces as the actors look into the camera — joy in simply being seen.

That kind of an alloyed excitement and pleasure in not just being in front of the camera but being in front of the camera with other actors of color and being able to share that experience. And you could feel that enthusiasm of being able to do something for the first time with other actors of color that they maybe only got to do on stage, if ever. For me, that’s the undeniable through-line for movies of that period. Even the ones that don’t succeed in conventional terms are about that level of connection that brings a unique experience to us as movie watchers.