Patrick Flynn could teach people a thing or two about being in a band. After his initial run with 2000s Boston hardcore mainstays Have Heart, Flynn picked up the microphone again in 2014, this time for one of the best bands on the planet, Fiddlehead.

But Flynn could also teach people a thing or two about history. For that matter, he actually does teach plenty of teenagers about it as a high school history teacher. It works out for the vocalist, as his Fiddlehead bandmates are content to primarily tour weekends and school breaks, and his colleagues and students are fairly understanding about his summer job not exactly being like everyone else’s.

SPIN spoke with the frontman about how he balances life between the stage and the classroom, the similarities and differences between lyrics and lesson plans, and much more.

SPIN: How do you balance the band with your academic career?

Patrick Flynn: While I was in college, I had a nice balance of two different things going on. Coming out of high school with Have Heart, I knew people who decided to have their bands just tour full time — and I saw them quickly burn out, and the public burn out on them. And then I noticed with Have Heart that we would only tour on weekends regionally — because that’s all we could do on the weekends — and when we had some type of winter break, summer break or spring break, we would do something a little bit longer and farther reaching. It made sense to me that it was a good schedule, because we weren’t always in people’s faces, so when we would come back to places, it was a bit more envied or looked forward to.

We would play every now and then with Cold World, and I remember Alex Russin saying “Oh, I wish I could tour as much as you guys.” But I remember thinking “I wish I could tour as not frequently as you.” Not that I hated it, but he was studying to become a lawyer, and I remember watching Cold World play and they would just demolish it every time. I remember thinking “Man, if they just toured a little bit more, it’d be fucking insane.” But in reality, I think that their sporadic playing is what gave them such long legs. Even today, whenever they play, it’s still a pretty big deal. The thing that kind of took me away from the touring world was just the distance from loved ones and not seeing them, and then also my brain turning into mush. So all of that just helps me appreciate the prospect of not having to decide on one thing — especially since I have no real ambition for giant mainstream fame or anything like that. I’m completely content with just playing on a monthly basis and then a little bit over the summer. It’s like the ROTC style of one weekend per month and three weeks each summer or something like that.

Are the creative aspects of teaching and songwriting similar for you at all?

There are actually a lot of shared elements for me. My lyric writing experience has certainly informed my lesson writing experience. I’ve always struggled to just take a lesson plan that’s already made, even though you can find a lesson for anything. I still struggle to take someone else’s lesson and then just make it work. I have to be totally involved in the same way that I am in the songwriting process. I have to be there the whole way through. During the music writing, I’m the singer, so I don’t really play an instrument, but I have to be at every left and right turn. Lesson writing is pretty similar in that I have a personal need to be on the creative end of it. It’s obviously much more frequent, in that I’m constantly redesigning and trimming things from lessons I’ve made over the last 10 years, but it’s similar in terms of the need to be creative and original.

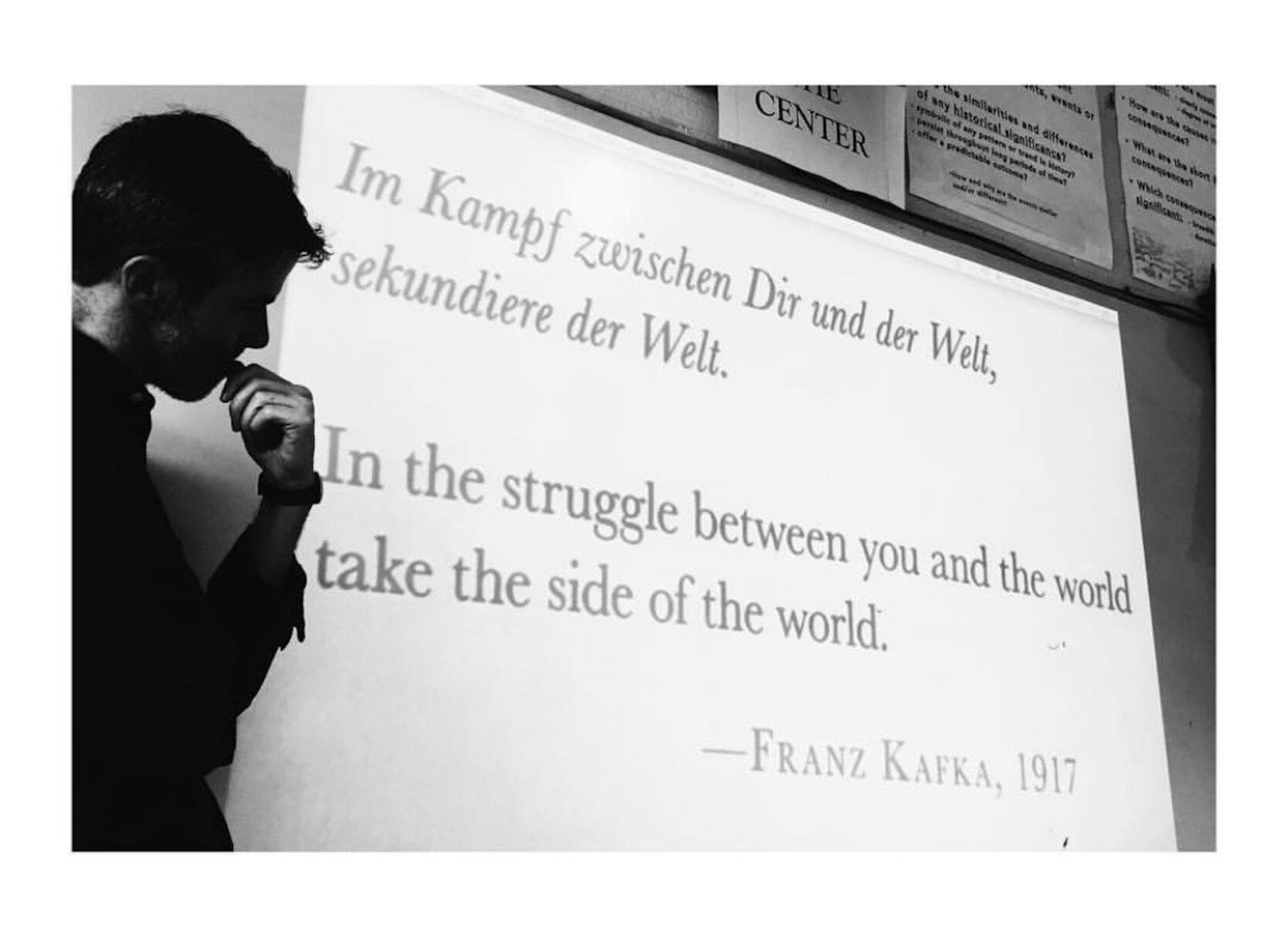

Perhaps in contrast, I teach AP World History and a course on modern world history, like the Holocaust. The school of thought that I’m from really puts literacy skills at the front, but when I say literacy, I don’t just mean reading and writing. I mean a disciplined literacy of history, which is typically reserved for graduate degree-level students. But a lot of great research shows that if you lead with teaching students the specific discipline skills of history — otherwise known as the “historical method” or “historical thinking” — they actually learn a cognitive critical thinking skill, which helps them retain the content better. So a really good lesson for me is one that has some kind of problem in it, and you have to apply a specific skill set of historical thinking to solve that problem. It may be the skill set of determining historical reality by way of knowing how to analyze a historical primary source or secondary source, or determining why this event happened. “Your textbook says this, but these documents say differently. Can we confirm the textbook’s argument or augment it a little bit by applying your understanding of the situation?” It engages the people thinking about it.

On the flip side, with lyric writing, there’s a level of skepticism that has been central to what I have found to draw an audience’s best response to music that I’ve been a part of. There are a lot of contradictions you can find embedded within a lot of the lyrics that I’ve written — not in terms of philosophical contradictions, but sonic contradictions. For example, the Fiddlehead record Springtime and Blind has a very pretty exterior and is named after a very pleasant-looking food. But the lyrical content on that record is actually pretty depressing, pretty dark and pretty grief-stricken.

Did punk and hardcore shape your decision to become a history teacher at all?

Well, I was a really quiet, but deeply thoughtful kid in high school — and then on weekends, I’d be screaming in people’s faces. I was a little more affable in my own little subcultural tribe at punk shows, but I would still come to school and just be looking closely at what I was learning there, or if I was understanding it at all. I remember thinking very early on that I wanted to teach history, and I remember thinking that I could fit in within the academic circles, because it wasn’t that I was shy or unconfident, but I was just deeply in thought and skeptical of deeply certain people.

When I started going to shows in the ‘90s, there were still elements of what was a very opinionated era of hardcore — whether it be in terms of animal rights or even an almost militant take on straight edge. Something about that always reminded me of the football jock/frat boy certainty and confidence that I just never liked and never vibed with, and there’s something about history that sort of says “I don’t really think it’s totally finished, because we’re having competing narratives.” I had some good teachers along the way that showed me that history is, in many respects, about consensus and agreed upon ideas of how things happened, which explains my reservations to not be like “This is my understanding of the world. You should all believe it.” If anything, history’s taught me to be wary of anybody who has a deep conviction to an ideology or something like that.

How has teaching shaped your music career and vice versa?

Well during the music writing process — and even when playing sometimes — I’m not always leading the show. While I might be leading the show in class a lot of the time, some of the best moments in my classroom experience have been when I just stepped back and let the students figure things out. This thing called “reciprocal teaching” is actually one of those powerful ways in which students not only learn content, but also make connections. Sometimes you just have to shift gears from always leading to seeing how intensely things happen when you just shut the fuck up and get out of the discussion in the classroom. Students tend to really dive in sometimes, and if they take a left turn, I say “Well, I see what you’re saying, but let’s not forget about this” and redirect it back. In the songwriting process, I — as the non-instrument player — have to know when to just let it ride and let things grow, but then to reinsert my expertise as the final instrument on the song and knowing when to be like “Alright, that’s let’s not lose the forest for the trees here.”

It’s also helped me get a better understanding of young people. This might sound weird, but I don’t necessarily love children. If anything, one of the things that drove me to education was a level of resentment towards adolescent apathy and the ways in which adults and adolescents alike greenlight mean-spirited behavior like bullying. I was on the receiving end of a lot of that growing up — first as an Army brat, then as the new kid and then as an outcast — and I hated all of that experience. I hated it so much that I got into punk rock, and I don’t want too many people turning to punk rock to survive. So I didn’t get into this role to be an anti-bullying politician in the classroom, but there were times where as a kid I was thinking “I really wish the adult in the room would show up here and recognize their role of not necessarily constantly calling shit out, but having a greater presence or leadership in the classroom.”

Seeing as there’s not really a blueprint for how to be a history teacher and a punk rocker on the weekends and summers, is there any advice you’d give to someone who wants to follow in those footsteps?

I think it’s totally possible for anyone to have those two lives, and I’ve had relative success in this subculture, which I’m really grateful for. I think a lot of that has come from not being interested in being successful and just being genuine about it. It clears the mind of any distractions, and what you’re interested in should be creating good art and having fun instead of being concerned with the more materialistic things that can come from presenting good art. I’ve worked with people in the past who, regrettably, are clearly interested in some of the more material benefits that come with creating good art, and I can’t work with them. There’s a disconnection in the songwriting process and even in the conversations. I’m much more clear-headed in the songwriting process this way, and that’s just so essential for creating good art. I’m really proud of the stuff that I’ve created over the years, especially with Fiddlehead. I’m able to pursue two major passions, but also be much more present in the process.

Is there anything else you’d want to share about that intersection of academia and punk rock?

I think being in a state of consistent learning is just good for punk in general. That doesn’t mean you have to be like Billy Bragg or Crass. You don’t have to come to the table with this excessively informed and overly pedantic approach to writing lyrics. But I’ve found that you can tell when music is coming from people who are hungry for knowledge and learning. It doesn’t have to be in a bunch of fucking books or history lectures or reading every fucking David Foster Wallace story. It can come from just being a curious human being and looking to question what history has taught us — not necessarily to find something new, but something different or unique at least.