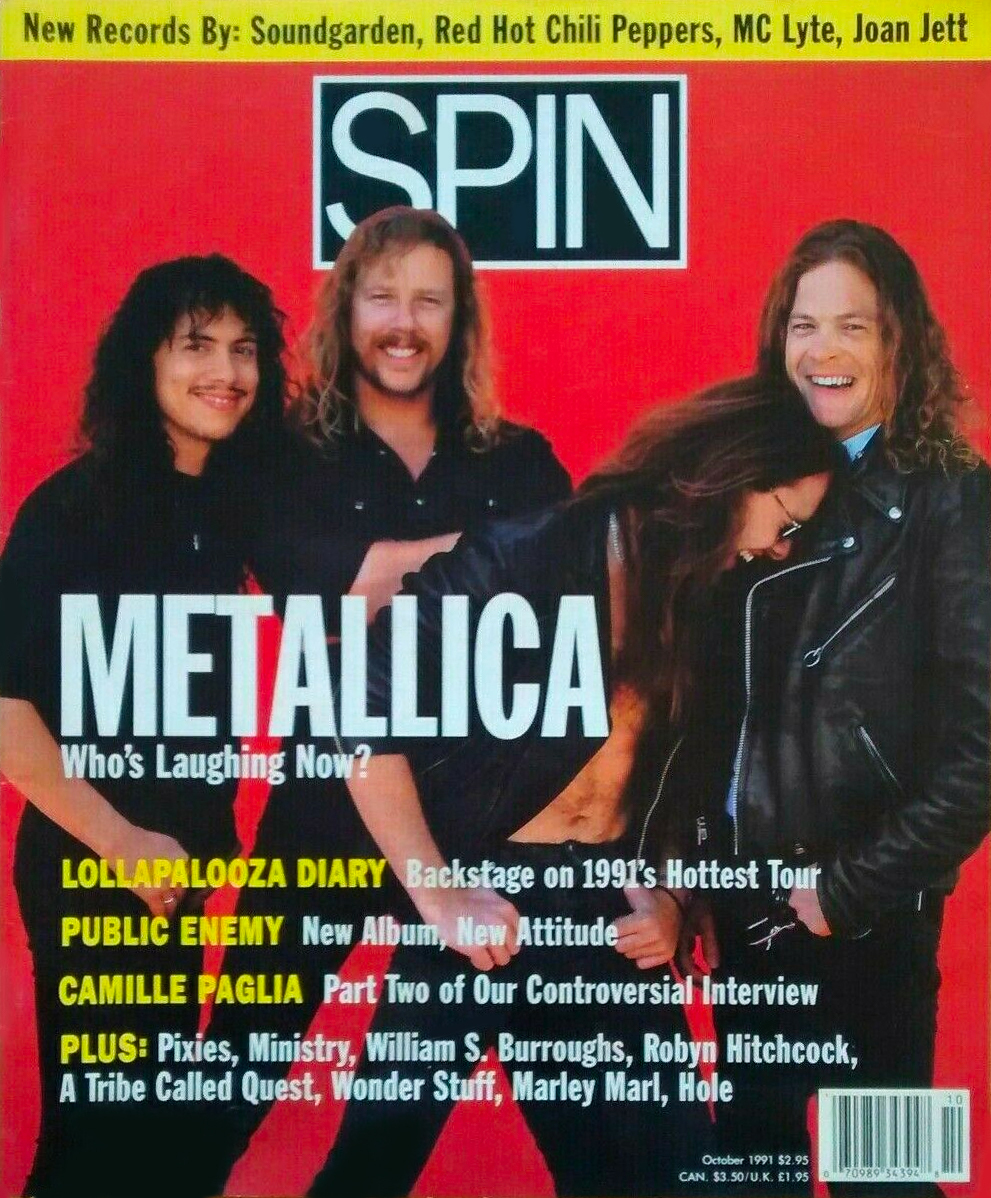

This article originally appeared in the October 1991 issue of SPIN. In honor of Metallica playing their 40th anniversary shows in San Francisco this weekend, we’re republishing it here.

Near the end of Metallica‘s last tour, rhythm guitarist and vocalist James Hetfield got the idea for a party. “It was going to be great,” he says. “Farm animals, midgets serving drinks, tits everywhere—that kind of shit. Jägermeister ended up sponsoring the thing and giving away free drinks. There were barf puddles everywhere.”

There was only one problem. “The midgets wouldn’t do it. They heard the name Metallica, and they said no, we’ll get abused.”

The midgets weren’t the first ones to balk at the name Metallica. For what a name it is! It suggests not a band but an Orwellian nation, like Oceania. That extra A on the end is so pseudoscientific and official—it is perfect.

Much as I liked the name, I never liked the band. They had supposedly revitalized metal by paving the way for Slayer, Megadeth, and countless “thrashers,” but those bands invariably had a megadearth of ideas that mixed the worst aspects of metal (bad haircuts, self-serving riffs) with the worst parts of punk (lousy vocals, calculated anger).

Ironically, Metallica never meant to popularize this futile style; indeed, Hetfield explains that he began playing speed riffs and yelling in a desperate effort to jar the airhead audiences at the band’s earliest L.A. gigs. The less people listened, the more “we kinda shoved it down their necks a little harder each time.”

Metallica, though, eventually distinguished itself from the horde with pastoral patches and progressive pizzazz. But still . . . I resented critics who rationalized them as somehow “punk.” And admittedly, I was spooked by the new generation of two million kids who did like them, legions of zealous misfits that I was too old to understand—even though I was the same age as the guys in Metallica and we’d all graduated from the school of hard rocks while growing up in the sunny Cali suburbs of the ’70s.

But like a lot of people, I wanted to like Metallica, a not uncommon desire according to lead guitarist Kirk Hammett. “I have a theory that people want to like Metallica, it’s just that they can’t find the right reasons to. Why do people like us? I listen and don’t hear it. This album won’t attract that kind of element.”

Cool as they were, Metallica had—by the end of the 251-date tour for 1988’s … And Justice for All—grown tired of jagged riffs and shifting time signatures. The band was also sorely lacking in one particular department. “We wanted more of a groove thing,” says Hammett, “and when people hear this album, they’re gonna say, ‘What is this? Sly and the Family Stone?'”

Well, not exactly. But the group’s sixth release, Metallica, is at once a seminal departure from and shrewd streamlining of its previous oeuvre. Historically, it’s like when Rush conjured up the surprise 1980 hit “Spirit of the Radio,” following years of insecure jamming (an idea that drummer Lars Ulrich seconds, saying, “More than any other band, we are like Rush”).

Sociologically, it’s the album that will make it safe to like Metallica—much as “Losing My Religion” catapulted R.E.M. into the megamainstream. And contrary to what Hammett says, it should not detract from the band’s coolness: Its hardcore following has been screaming sellout since its second LP, Ride the Lightning, and, as it happens, this new disc recaptures the raw power of songs like “Seek and Destroy” from the band’s bare-bones 1983 debut, Kill ‘Em All.

Complementing this new simplicity is the album’s cover art—not goofy heavy metal cartoonery but simply the group’s logo on a black background. This in turn reflects their belief that the startling new music—from the sitar on “Wherever I May Roam” to the Celtic hillbilly shuffle of “Don’t Tread on Me” to the Beatlesque harmonies on “Nothing Else Matters”—really does speak for itself.

Such generic packaging doesn’t mean, however, that Metallica is still as antisocial as it once was. After years of avoiding video, the band’s finally gunning for MTV, and in monster rockers like “Enter Sandman” (already in heavy rotation) it has the right ammunition.

But if you think this means Metallica’s gone soft, think again. Yes, Hetfield and drummer Lars Ulrich laid off the Jägermeister when it nearly gave them ulcers—but they have hardly stopped drinking. And yes, the maturation of the music might suggest that the band itself has been domesticated—but Hammett, Ulrich, and bassist Jason Newsted are all recently divorced and ready to hit the road.

No, Metallica has confounded the rock myths of immaturity and disposability by striking a perfect balance between growing up and retreating to roots. A lot of credit must go to coproducer Bob Rock, whose Midas touch has made millions for mainstream metal acts from Mötley Crüe to Loverboy. Among other innovations, Rock had the band cut its basic tracks live and suggested that Hetfield harmonize certain vocals. When he encountered reluctance, Rock (his real name) resorted to trickery: “I’d get them to do stuff real quickly and say, ‘We’ll come back to it later.’ But we hardly ever went back.”

Ultimately, though, any sellout accusations should be leveled at the four guys who, after all, wrote the songs before Rock ever tinkered with them. The four guys who allegedly have a thing for porno and snuff films. The four guys …

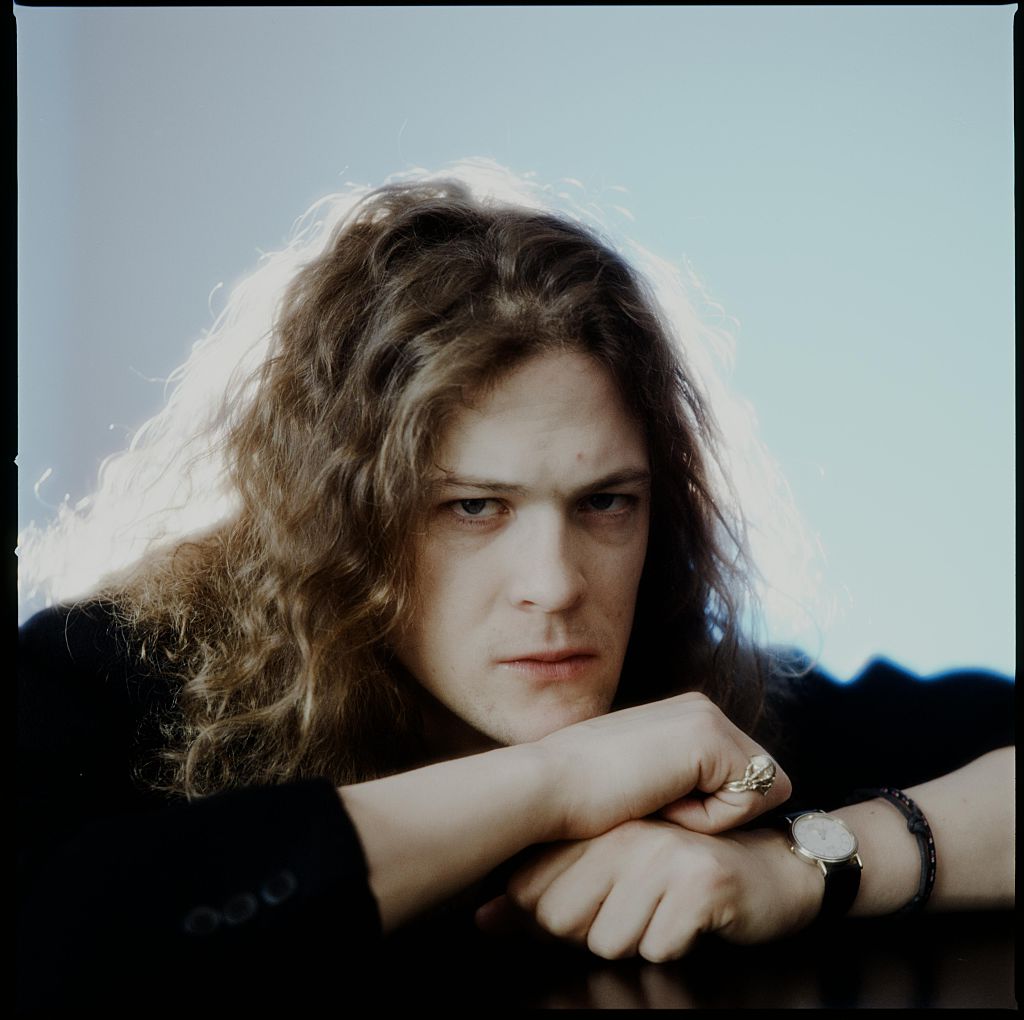

Metallica bassist Jason Newsted is scowling at me. You’d furrow your brow a lot, too, if you had his gig. For although he’s been in the band over five years, he still isn’t the bassist. That title will always belong to the late Cliff Burton, who was crushed when the group’s tour bus rolled over in Sweden on September 27, 1986.

Burton, who grew up with Faith No More guitarist Jim Martin near San Francisco, was a cross between Clint Eastwood and E. F. Hutton: Didn’t say much, but when he did, people listened. Especially Hetfield and Ulrich, who were pups with peach fuzz and acne when they relocated Metallica to the Bay Area in late ’81 to be closer to Cliff. Burton had flavor: He wore bell-bottoms, read H.P. Lovecraft, studied piano, and even went to junior college. “He taught James and Kirk a lot of different harmonies and theory,” says Newsted, who was in the Phoenix band Flotsam and Jetsam prior to replacing Burton.

That privilege involved certain initiation rites. When Newsted tried to play Milquetoast and go to bed early on his first tour, says drummer Lars Ulrich, “Fifteen of us would sit at the bar, charge a thousand-dollar tab to him, take his door off the hinges, and break his room down. The next day, we’d put him in a limo all by himself—that type of vibe.”

Newsted could deal with that type of vibe. He could even deal with the vibe at the Detroit concert—attended by family and friends—that Hetfield virtually ruined by chain-puking throughout. What Newsted couldn’t deal with, however, was the vibe (or lack of one) that he got from playing with Metallica. “I wouldn’t have been able to deal with another record like Justice,” he insists. “Quitting would have been the hugest bad career move, but I’d have gone on and done my Elvis band or whatever.”

The problem was simple: There was no audible bass in Metallica’s songs. In fact, Newsted’s efforts weren’t even pumped in to the drummer’s monitor onstage. In order to create an “actual rhythm section,” Newsted stopped duping Hetfield’s guitar and started following Ulrich instead. Plus, he enthuses, “This time we were lucky to have a producer who helped my sound hold up under the big drum and guitar.”

The results are staggering. By the third song, “Holier Than Thou,” Newsted is even busting out of his subterranean drone with a buoyant bass break à la Jane’s Addiction’s “Been Caught Stealing.”

Which is why Jason Newsted is a happy guy, even as he coaxes the blues from a beautiful steel guitar—and which he’ll no doubt use at the jam sessions of the Maxwell House Ranch Band that he, Hetfield, Jim Martin, and Jim’s brother Lou like to organize. The same jam sessions that Burton used to sit in on.

Perhaps Kirk Hammett will be sittin’ in on those House Ranch Band hootenannies some day, though low-down, hoedown blues isn’t the first thing you think of when hearing his past work—solos that he himself describes as “machinelike.”

Like Jason Newsted, however, Kirk Hammett has gone through a sea change on this latest album.

“On one song, I played the solo and went, Hello! and Bob just looked at me and said, Man, you’re not even playing with the band.”

Like Lisa Simpson on sax or something?

“Yeah, exactly—and I’m like, Okay, what the fuck would you do, Mr. Producer Guy from Canada? And he goes, Well, you should play more bluesy, sustained notes. I’m listening, and I’m shocked because—we’re talking about you,” he yells at Bob Rock as the producer heads into the bowels of A&M to mix the new album. “I was shocked because for once he was right!”

Though he grew up in Haight-Ashbury as a child of the summer of love, Hammett had literally gone by the book until cutting the sassy, wah-wah–soaked solos on the new LP. “I brought my guitar book to algebra class,” he says, and used to tell schoolmate Les Claypool, now of Primus, “I’m a guitar player, man.”

Hammett joined Metallica in 1983, when the band canned original lead guitarist Dave Mustaine, whose playing wasn’t “emotional or melodic” enough—and whose drinking was more than even “Alcoholica” could take.

Mustaine was hardly as cool as Cliff Burton, so Hammett didn’t suffer the same rigmarole as Newsted. Hammett did, however, have to join on the eve of recording the band’s 1983 debut, Kill ‘Em All (which they fought in vain to call Metal Up Your Ass). Kill ‘Em All unexpectedly sold 300,000 copies, and as Ulrich says, “All of a sudden we had a record out, we were touring, but we really couldn’t play.” So Ulrich took drum lessons and Hammett began studying under guitar guru Joe Satriani.

Amazing as Satriani is, his clinical sound only reinforced Hammett’s algebraic chops. His solos were sometimes cool, but more often just cold. “There was a point when I really stuck to my technique, but nowadays it’s the feel and what’s appropriate for the moment.”

“It’s a joke, right?” James Hetfield is asking about Perry Farrell and Ice-T’s cover of “Don’t Call Me N****r Whitey” by Sly Stone. “‘Cause that Perry guy is pretty open-minded.”

The subject came up when I asked Hetfield about a “rap” he once recorded with lyrics that you’d never accuse of being open-minded. “Rap was just starting, and I did a parody that had the N word—but you can’t say n****r, especially whitey.” The title of the rap was simply “N****r.”

So the lyricist, singer, and riffmeister who accounts for 60 percent of Metallica’s sound is a bigot, is that it? Not exactly. After all, Lloyd Grant, Metallica’s original lead guitarist before Dave Mustaine, was black. But Hetfield is definitely, along with hunting partner Jim Martin, a would-be good ol’ boy, a …

“Go ahead and say it,” he roars. “Redneck!!”

With his thick build, squeezed into jeans and cowboy boots, he certainly looks it. That his father was a Nebraska-born trucker since retired to Arkansas gives the image legitimacy—as does Hetfield’s own interest in Lynyrd Skynyrd and hunting. Hetfield himself is animal-like—what you’d call a bear of a man if the blond Fu Manchu mustache didn’t lend his face a leonine look.

I was warned he’d kill me if I asked him about the rap—or about the bowie knife his father passed on to him which had allegedly been used to kill a black man. He does freak when I bring up the knife (“That’s not true!” he stammers unconvincingly), but otherwise he’s disarmingly friendly and surprisingly open about his love of “titty bars” and the epic Jägermeister binge that almost killed him and Ulrich.

Given his druthers, Hetfield would abandon the A&M sessions and hang out at the Maxwell House Ranch near San Francisco, sipping porch. “It’s port wine, but we call it porch ’cause that’s where we slug it while we’re jamming.” How do they play when juiced up on porch? “Fucking obnoxious and loud,” says Hetfield. “Jim’s brother, Lou, is good at making up lyrics on the spot—there’s one about Larry Singleton, the guy who chopped that girl’s arms off. We got these oil drums and bang on them. If someone was driving up in those hills, man, they better get out of there. There’s some sick shit going on.”

Such “sick shit” doesn’t find its way into Metallica’s songs much any more. The new single, “Enter Sandman,” may be a bit of a scary bedtime story, but gone for the most part are songs about being trapped under ice or being strapped to the electric chair. Hetfield had already strayed from headbangcr clichés on …And Justice for All, which explored the shortcomings of our legal system, but what he’s done this time is present the other side of the almighty dollar. “On Justice, we stayed to the shitty side—not America sucks! but pointing out the scary parts. But certain people, they’re way out of hand with that shit. Go fucking somewhere else then, man.”

“Don’t Tread on Me,” inspired by Hetfield’s fascination with the Revolutionary War flag depicting new America as a rattlesnake, even says, “Love it or leave it.” In addition, the “complainers” (read liberals) are targeted in “My Friend of Misery,” while fashion victims get theirs in “Holier Than Thou.” The theme is simple: Get yer own shit together before messin’ with someone else’s.

Such rugged individualism is sometimes tempered by existential doubt (“Through the Never”) and is most palatable when couched in the one-with-natureisms found in “Of Wolf and Man” (the song Ted Nugent wasn’t man enough to write) and “Wherever I May Roam” (adopted by the recently divorced other three band members as their theme song).

However, when I tell him that his Spartan, earthy writing style reminds me of Hemingway’s, his only reply is: “I’m not up on who wrote that, or any of that stuff, really.”

What he’s up on is his own stuff. His commitment to improving himself as a singer and songwriter is as awesome as his rhythm-guitar style, arguably the most inventive in the metal canon. He scoffs at “bands who watch the news and write a song. Fuck off! It’s so easy. Like, come on.” Nor does he have patience for the pop theorists who think it all must be a joke: “Everyone thinks that metal is for young kids, that’s it’s immature music. But I just don’t know … ”

By practicing the same philosophy he preaches, Hetfield makes it easier to take his more reactionary sentiments. He also provides a window into his personality. His lust for life may stem from a misspent childhood. On the one hand, his father was a strict Christian Scientist, so Hetfield would have to leave the room during health class at school. “I really felt on my own,” he has said. “Not proud, but that they were hiding stuff from me.” On the other hand, his father left the family when James entered high school. “He was raging around on our support money and that pissed me off. Now I understand, but … ”

When Hetfield opens up, it’s tempting to assume that his Evil Metal Vocalist persona is bogus, that underneath he’s just a peckerwood—and a sensitive one at that. Then again, while talking about his ambivalence toward school, and reading in particular, he suddenly perks up. “Science was always fun because you got to do shit. You didn’t have to sit at a goddamn book. You got to play with fire, cut frogs open, 000!—freak the girls out.”

Now Hetfield freaks girls out in a different way. One Elektra publicist even thinks that the sultry vocal stylings on the love song “Nothing Else Matters” are “sexy.” Sexy? Metallica?!

So what’s he gonna do when these newfound female fans want to clap along in concert with one of the catchier new tunes? “I’ll give ’em a clap!” he sniggers.

In a year or so, when the clapping has ceased and the new album finally falls off the charts, Metallica will take a well-earned rest. James’ll go duck hunting, Jason’ll crank the reggae and play hoops, Kirk will flip through his Japanese comics, and Lars—well, Lars, in his own words, “is more itchy than the other guys. Two weeks after the tour I’m, like, Fuck, let’s do something!”

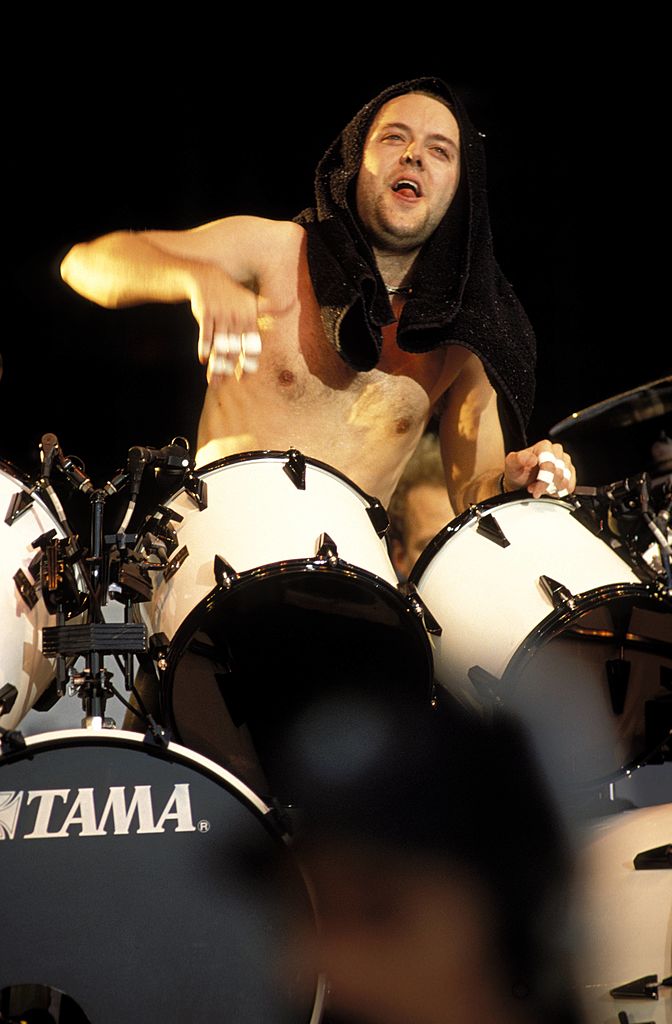

James Hetfield may be Metallica, but hyper little Lars Ulrich, who looks like a cross between Paul McCartney and the Wild Man of Borneo, lives the band. “It sounds so dumb,” he says, “but I’m basically just rock ‘n’ roll music, or metal—that’s all there is for me.”

While the others flee during lulls in recording, Ulrich stays perched on the engineer’s shoulder. While the others avoid L.A., Ulrich isn’t averse to going for a drink with Slash and winding up on all fours in the gutter. This social ease comes from his gift for gab. In a tart, almost contemptuous Danish accent, he’ll declaim on any and all subjects. More than the others, he’s comfortable looking at the big picture. While they gingerly distance themselves from previous albums, Lars “doesn’t talk shit” about the old stuff “because that’s where our heads were at the time.” He alone notes that the group’s initiation of bassist Newsted reflected upon its own inability to deal with Cliff Burton’s death.

So where does all this circumspection come from? Same place as Hetfield’s enormous will: the family. Ulrich’s old man was a Danish tennis pro (and Lars himself a ranked junior), a long-hair jazz critic who took Lars to his first concert (Deep Purple) when the lad was but nine. He also played his son Miles and Bird records at home, and took him on the tennis circuit. “I traveled more before I was ten than I have with Metallica,” recalls Ulrich, who ends up playing a cosmopolitan Mick to Hetfield’s trailer park Keith.

After getting his first drum kit, Ulrich found in music his “one escape from the discipline of tennis.” And by the time his family moved from Denmark to Los Angeles in 1980 (to facilitate Ulrich’s budding tennis career), the demon seed had already sprouted.

“After six months, the tennis fizzed out. I was fuckin’ sixteen and started smokin’ pot, lookin’ at girls, growing my hair, and looking for other people to play with.” Infested with overrated new-wavers like X, L.A. was “a barren wasteland for metal,” he remembers. “Bread heads would call and say, ‘Yeah, I’m into metal—you know, REO’ And I was, like, I don’t think so.”

Like a metal Morrissey, Ulrich pored over the music papers, bought imports, even went to England to hang with Diamond Head and other heroes of British heavy metal. Upon returning from overseas, he phoned this quiet kid called James he’d played with once before, and the rest, as they say, is history ….

Like Hammett, however, Ulrich took lessons because he felt insecure about his abilities. So by the time . . . And Justice for All came out in 1988, he was outdoing Neil Peart with insane double kick-drum antics and roto-tom fills. “Some of the progressive things became boring to play live. You ended up playing more with your mind than your body, and it was difficult to get a bond going with the audience.”

There won’t be that problem on this tour, for as Ulrich says, he “finally has a vibe goin’ in a major fuckin’ way.” He says he wanted to get away from Peartian paradiddles and back to the basics employed by Charlie Watts and AC/DC’s prehensile ex-skinsman Phil Rudd. What he actually came up with is a golden mean between the two extremes: a loud, deliberate stomp peppered with offbeat crashes and unexpected ticks.

Nowhere is this killer batterie more evident than on “Sad but True,” a track that Bob Rock, after hearing only a demo, labeled “the ‘Kashmir’ of the ’90s.” Both the band and Rock cringe at this description now, but they do allow that the singular guitar riff is on that epic scale. But it’s not only the guitar but the cannonlike drums that make the comparison apt. For although it’s sad that it’s taken this long for someone to equal John Bonham’s massive attack, it’s also true that Lars Ulrich has shown himself to be man enough to finally do it.

As my interview with Lars Ulrich wound down, one question kept nagging: What would Cliff have thought of this new direction?

“Whoa! That’s a good one.” For once Ulrich is caught offguard—but just for a second. “If he was here today he would hopefully feel the same way. The great thing about Cliff was how abstract he approached the bass. But I wouldn’t be painting the whole picture if I didn’t say that once in a while we tried to get him to tone down a little bit. And sometimes that wasn’t the easiest thing to do.”

Like they say, sad but true.