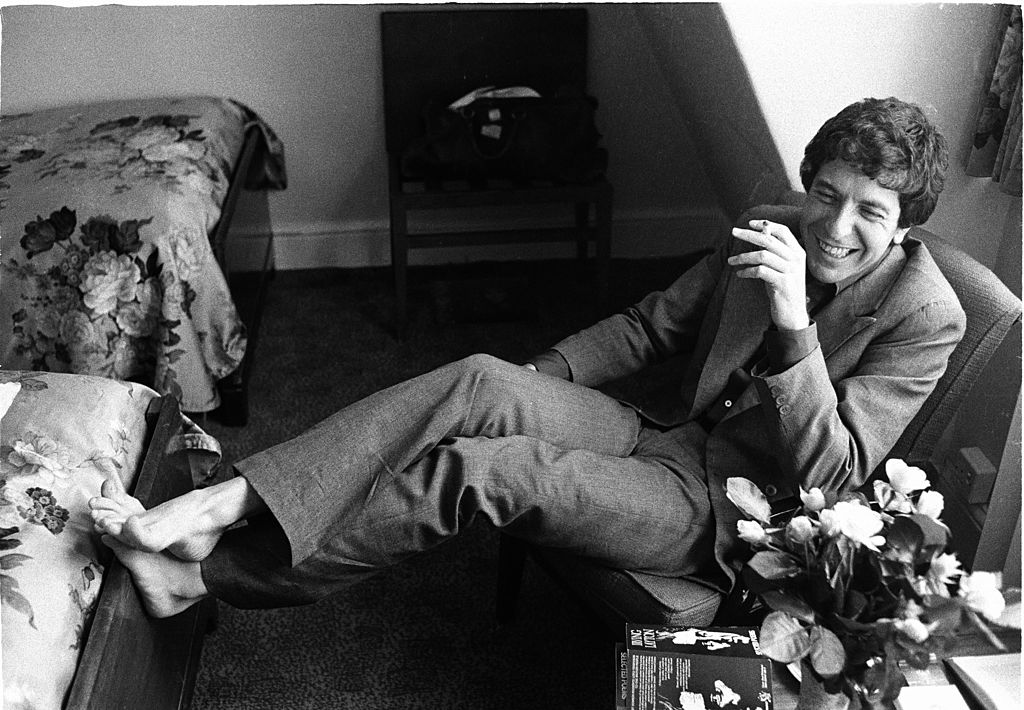

Leonard Cohen has been a huge inspiration for me as a songwriter. But in a different way than most other artists or bands, which one might otherwise regard as obvious direct musical “influences” on my band Communions.

Although our music isn’t rooted in folk—post-punk, Britpop and alt-rock are perhaps our biggest genre influences—the influence of Leonard Cohen enters through a different route, which is, first and foremost, lyrical. But it wasn’t until I began writing our upcoming record Pure FabricationthatI really allowed myself to embrace Cohen as an influence; that is, I allowed his influence to directly seep into my own writing. Cohen’s poetic approach to music has always cast its shadow over my musical consciousness, but had previously been latent in my expression. I think that’s because there’s something daunting about attempting to emulate guys like Cohen, or similarly, someone like Bob Dylan. For me, both are the two towering giants of my musical upbringing, two pinnacles of 60’s music bred from a time where music had a close-knit connection to poetry, and who constitute the foundation of the kind of songwriter I admire.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly where this influence begins and ends in my own artistic output, but I think it begins with an ideal of wanting the lyrics that accompany the music to be able to stand on their own, of wanting the words to be able to have a poetic impact in their own right. This is something I always appreciated about Cohen’s songs. His lyrics aren’t just poetic, they could be gauged as actual poems—surreal, and filled with endless layers, which in turn makes the music endlessly re-listenable. This kind of approach to popular music was certainly incomparable to the popular rock ‘n roll of the ‘60s. In my mind, Cohen was a first-mover, and paved the way for a more introverted and intellectual kind of popular songwriting, proving that that sort of writing could resonate with an audience, and more importantly, that it would have longevity and stand the test of time. That, in itself, is inspiring.

The timelessness of his songs’ imagery is something significant. His songs are so dense with sensual images and provoking scenes that listening to his album Songs of Leonard Cohen is almost like a physical spatial experience—like revisiting an old house that you used to live in, or getting to inhabit a landscape again for a while. There is really no other music quite like it.

Songs of Leonard Cohen isn’t really a record I listen to so much as I ‘live’ with, in the sense that it’s an album I seem to replay during certain parts of the year; there’s something about it, that I associate with the cold, which makes it a fitting listen every autumn and winter—whether its because of the title of the song “Winter Lady” or due to the foggy, melancholic atmosphere of the record induced by the softly played flamenco guitar…I don’t know. Perhaps “living with”, or rather, “needing” these songs amidst the flux of seasonal change isn’t coincidental; there is something so soothing, almost meditative about songs like “Suzanne” or “Sisters of Mercy” that they have a real calming effect on me.

This meditative effect might also attest to the fact that I specifically sought out tickets to a Leonard Cohen concert during a time of personal upheaval. Despite being a musician, I’ve never extensively gone to concerts on my own accord (apart from cheap punk shows during my youth). At least, I can’t recall many times in my life where I’ve gone out of my way and bought “expensive” concert tickets. But one time I remember clearly was when I bought a ticket to see Cohen live in Seattle. After finishing high school in Copenhagen, Denmark (where I’m originally born), I had shortly moved back to Seattle (where my family and I had lived for 10 years) on my own, living on my friend’s couch, and with the intention of moving back to the States permanently. This was a confusing, tumultuous time for me—a time of existential crisis in which I was unsure which country I belonged to. I don’t remember why I went to the concert alone, but I remember being by myself, sitting in this huge stadium amongst others who were twice or three times my age, watching Leonard Cohen perform, and feeling like Ihad intimate access to an alternative world that transcended the world of problems that were going through my mind at the time. It was comforting to know that amid all of the chaos, the connection to this music constituted something unbreakable and constant, something that would not disappear, but would be a part of me wherever I was heading.