When Larry Cohn, 89, started collecting blues records in the 1940s and 1950s, little was written about the records, few had been reissued, and sometimes finding out what some even sounded like necessitated visiting with the owners of individual 78s—often the “only known copy.” In Cohn’s case these meetings were often with the “blues mafia,” a group of New York City area collectors who would eventually provide dubs of their rare discs for reissues on small specialist labels, many of which they ran themselves.

A long-time resident of L.A., Cohn still has the massive collection of records he’s acquired over his long life, and among the thousands of 78s are about 350 test pressings of alternative takes from pre-World War II sessions, many of which have never been issued. Like his friends in the “blues mafia” he has contributed to the reissue of early recordings, although his work has been on a much grander scale.

Notably, he produced the 1990 boxed set of Robert Johnson’s complete recordings from 1936 and 1937 for Sony. Initial company projections were low, but within a year the set had sold over half a million copies and the following year Cohn received a Grammy for Best Historical Album.

The set’s success allowed Cohn to dig deep into the archives of Sony, which in 1988 had acquired the CBS Record Group and its thousands of recordings from the 1920s and 1930s. For more than a decade, Cohn produced over 100 issues in Sony’s Roots n’ Blues series, mostly vintage blues but also old time country, Cajun and gospel music, as well as another 100 reissues from Sony’s catalog by artists including Willie Nelson, Taj Mahal, Carlos Santana and Pete Seeger. And today, at nearly 90, he continues to seek out new projects in the reissue field.

Cohn was born in Lebanon, Pennsylvania in 1932 and as a child moved with his family to the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn, which he recalls was a “mafia neighborhood … 75% Sicilian and about 25% Jewish.” His early passions were basketball and music.

“I started listening when I was nine, and by the time I was twelve I already had records—Jelly Roll Morton, Lead Belly and the boogie woogie guys—and it never stopped, I never lost my love for it.”

Radio, including a weekly program of boogie woogie piano, sparked his interest, and on Saturday nights he recalls listening to live broadcasts of Woody Herman’s band from New York clubs, the Jamboree country music program over Wheeling, West Virginia’s WWVA, and, if he stayed up late enough, church services from Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

“My dad would be screaming ‘Go to sleep!,’ so invariably I would pull the covers over me and put the Emerson radio under my chest.”

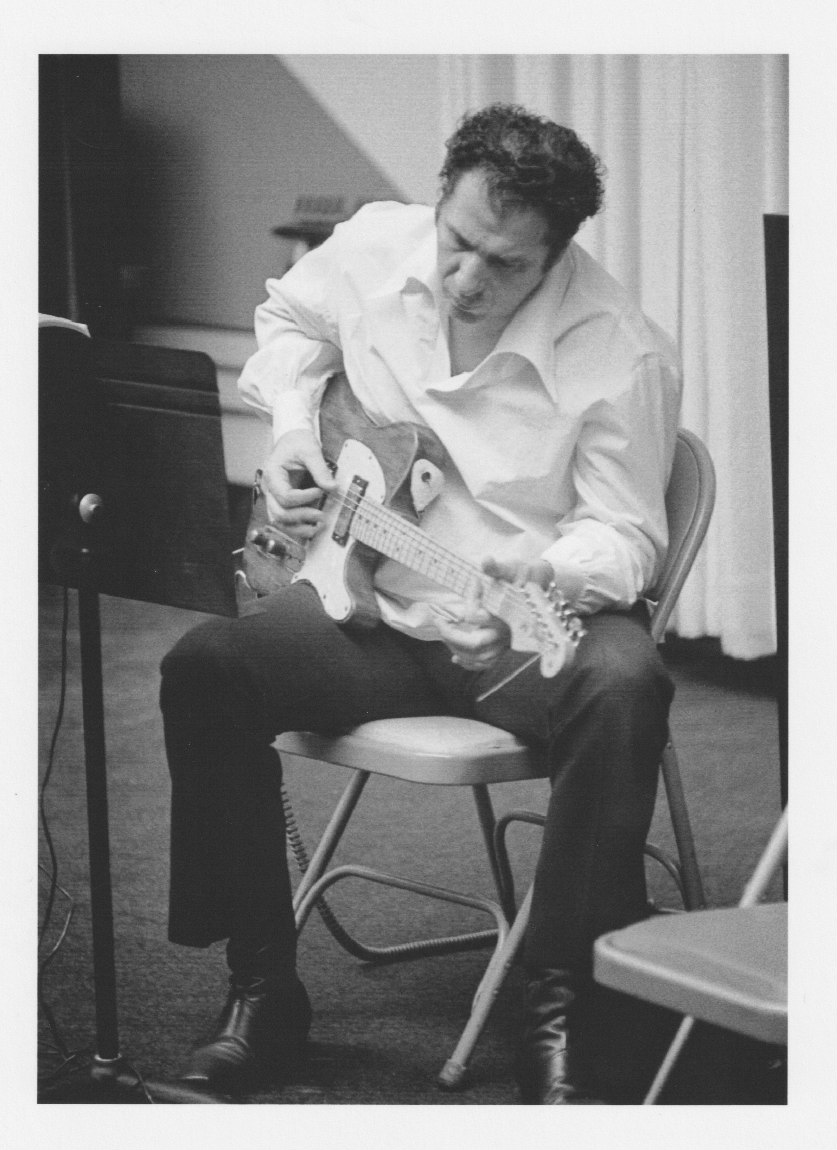

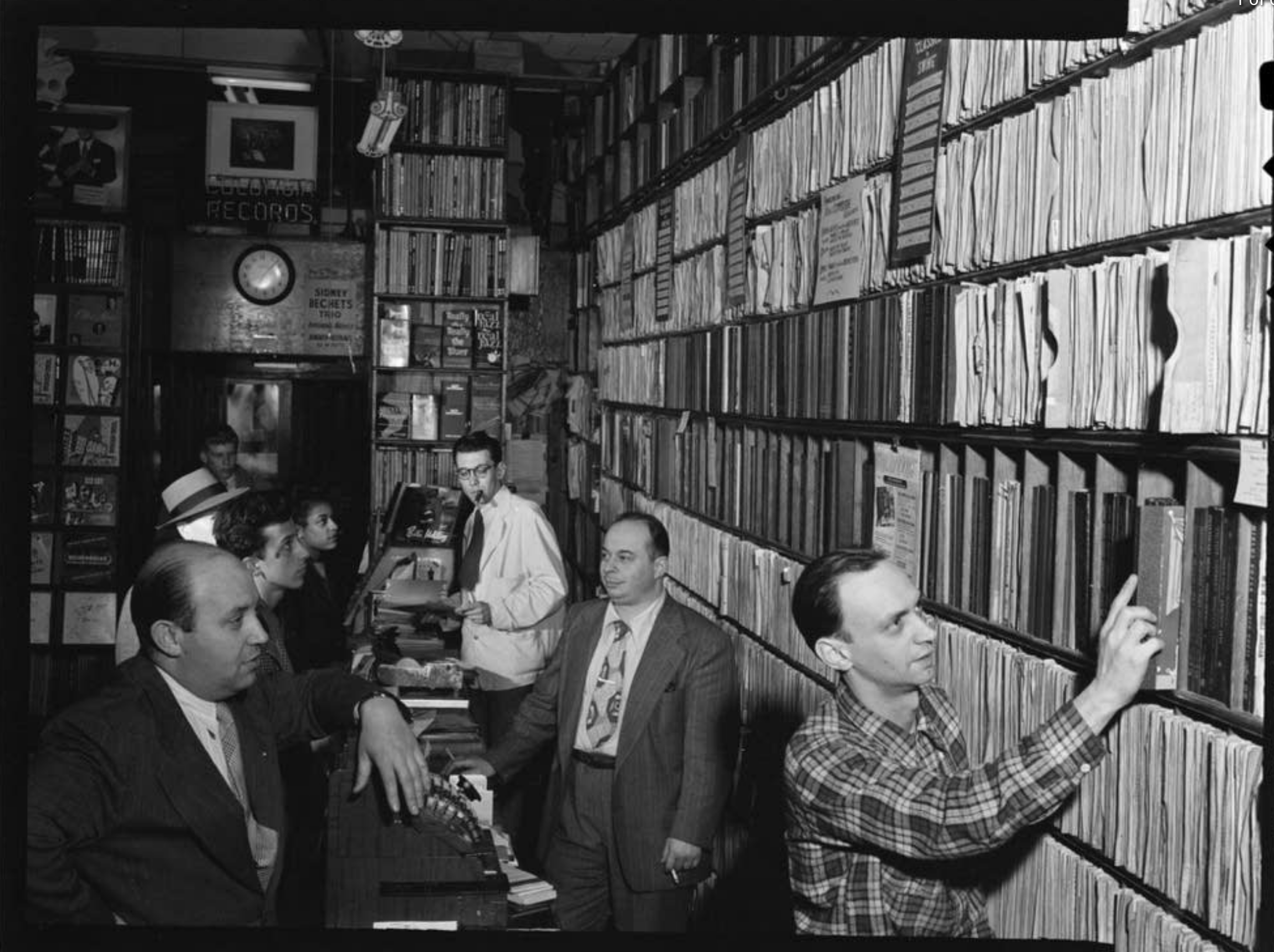

By his mid-teens Cohn was haunting record stores and junk shops with huge stacks of used 78s.

“Because I cut school so often I fell in with the coterie of collectors that hung at the Jazz Record Center on West 47th Street, Big Joe Clauberg’s place. Fifty cents a piece for Charlie Patton, Robert Johnson, Jelly Roll Morton and you name it. Nobody had any money to buy anything, at least I didn’t. I would save and maybe I could buy one record a month or something. It was all there, all the rare stuff. Clauberg was a huge guy, a former wrestler and boogie-woogie pianist. We got really chummy and I learned a great deal from the people that adopted me.”

Another favorite spot was the Commodore Record Store on 42nd Street, run by Jack Crystal, father of comedian Billy, and his brother-in-law Milt Gabler, a successful producer at Decca Records. The operation also included Commodore Records, an indie jazz label that most famously issued Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.”

“Jack adopted me,” says Cohn. “He would give me the furthermost back listening booth and he’d let me stay there all day playing music. I never had money to buy anything because I was so young.” Crystal also vetted Cohn’s girlfriend, who became his first wife, and let Cohn attend the many jazz shows he promoted at Central Plaza in the East Village. Already 6’1” by 13, Cohn also snuck into many shows around the city at clubs including Birdland.

After high school, Cohn attended City College of New York, but left during his junior year to join the Army during the Korean War.

“The irony was the war ended during basic training, so we were the first group to get 100% stateside orders. And I ended up playing basketball for the Army for two years, played in Madison Square Garden before the Knicks. We traveled all over the country, never wore uniforms, got daily per diems. We stayed in the best hotels, we were treated like royalty.”

After his discharge, Cohn completed college and attended Brooklyn Law School. “When I got out of law school I didn’t really want to be a lawyer. The government was giving federal agent exams and the starting salary was quite good. Long story short, I went and became an agent and worked with [Attorney General] Bobby Kennedy for a long time.”

Cohn worked as a Special Agent for both the Treasury and Justice departments, his duties, at both, were combatting the Mafia.

“Those guys never scared me,” Cohn recalls. “One thing about the higher echelon Mafia guys, there was no gratuitous violence with them. If it was purposeful, that was another story. Not just to be tough or that kind of thing. That’s why Joe [“Crazy Joe”] Gallo got killed [in 1972], because he was doing all that shit. They wanted to keep a low profile. If they gave you their word about something you could take their word to the bank. I’m not making the case for them as good guys, because they’re ruthless, but they were true to their word.”

Several years before fighting the criminal Mafia, Cohn had joined the less treacherous “blues mafia.” While an earlier generation of 78 collectors had largely ignored the blues in their pursuit of early jazz records, this group was more oriented to the “country blues” played by unaccompanied guitarists.

Some members, Cohn recalls, didn’t want to listen to anything past the mid-1930s, while he had more catholic tastes and during the listening sessions he hosted would play relative modernists including Lonnie Johnson and Blind Willie McTell, and even Johnny Cash. Cohn’s take on collecting was expressed in an article he wrote for 78 Quarterly: “The Blues Didn’t Die with Charley Patton’s Last Record” [a pioneer of Delta blues, Patton made his final recordings in 1934, the year he died].

Cohn started writing about music as an undergraduate and while working as a Special Agent received permission to write a music column for the big literary magazine Saturday Review. “Martin Williams, Stanley Dance and I divided [musical] things up. I did blues, folk, country and gospel—we were a good team. I wrote stories based upon in person interviews with Son House, John Hurt, about the Newport Folk Festival. I think we opened this up to a lot of people.”

He also penned liner notes for recordings of artists enjoying a second career during the “blues revival,” including Hurt, House, Big Joe Williams, John Lee Hooker, and Lightnin’ Hopkins, and for reissues of recordings by Lead Belly, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and Blind Willie McTell.

His collection today includes, according to him: “9000 LPs, about 3000 78s, 350 test pressings, between 18 – 20,000 CDs, and appx 1 – 2,000 reel to reel recordings and cassettes.”

His rarest is, he says without hesitation, a 78 by Freezone, “Indian Squaw Blues”, from around 1929/1930. Freezone only ever recorded one side of one 78, and there are only four known copies. He found his in a flea market in Memphis for 25 cents. The stall owner suggested he look down the line at some other boxes, to see if there was anything else he might like. It was a treasure trove of rare recordings and he bought many “nothing for more than 50 cents.” Then he saw a coveted Louis Armstrong record from 1932. “I have to charge you a dollar for that,” said the stall owner.

His favorite record is harder for him to say. He lands on Walter Roland, a pianist who accompanied a lot of blues singers. “There are very few mint copies of his stuff,” he says, going on to name-check “some Bessie Smith records” including the single “Kitchen Man Blues.” and Jimmy Rodgers — “I have about 125 records [of his] from the thirties.” And then he adds “anything on the American Music label. Meade “Lux” Lewis’ recording of ‘Honky Tonk Train Blues.’ Hits me emotionally.”

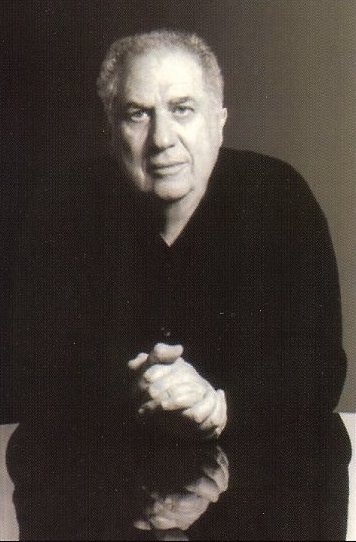

In 1968 Cohn retired from the government, and after writing a brief letter to CBS head William Paley, was hired as a trainee. Six months later he was floored when Clive Davis told him he was the new head of Epic Records. “My wife was waiting in the car and asked, ‘What happened? You look terrible.’”

At the helm of a major label Cohn worked across the spectrum musically, and his signings included Billy Joel, Redbone, REO Speedwagon, and Cheap Trick, as well as blues-oriented acts Fleetwood Mac, Johnny Otis, Shuggie Otis, Brenda Patterson, JoAnn Kelly and Edgar Winter.

In the early ‘70s Cohn was lured by the Playboy organization to run the new Playboy label; his work there included signing the pre-Abba “Björn and Benny” and establishing a production deal with Sam Phillips. He later spent a frustrating year negotiating with Bob Dylan to create a label that never materialized. In the mid-‘80s he relocated to Paris for five years.

Cohn’s return to CBS/Sony in 1990 came just as the CD was revolutionizing labels’ relationships to their back catalogs. The Robert Johnson set had been in the planning for 17 years when Cohn took it on, and he credits his background as a lawyer and a CBS exec for his success in getting it through the not inconsequential red tape.

No other blues albums sold anything near the Johnson set, but a rabid market for vintage blues brought respectable sales to all of Cohn’s issues in the Roots n’ Blues series. Cohn also brought early blues to broader attention in 1993 as the editor of the award-winning book Nothing But the Blues, which featured essays from major scholars.

Cohn was also responsible for reissues in other genres, and is particularly proud of career-spanning sets by Bill Monroe and Willie Nelson, who both reached out personally to Cohn to express their thanks. His greatest achievement at Sony, he says, was the 4-CD Roots n’ Blues: The Retrospective (1925-1950), which reflects his broad tastes and incredibly deep knowledge of the archives—45 of the 100+ tracks were previously unreleased.

This particular set is novel in how it organized songs from a wide range of genres—country and city blues, boogie woogie, gospel, sermons, sacred harp, Cajun, old-time country, western swing and bluegrass—chronologically rather than in terms of genre, so the listener gets a unique experience of hearing the wide range of issues from a particular year side by side.

Cohn says it was a tribute to the eccentric folklorist Harry Smith, compiler of the 1952 six-LP set Anthology of American Folk Music on Folkways Records. Smith had likewise ignored genre in structuring the diverse set of recordings from the ’20s and early ’30s, which had a profound influence on the emergent “folk revival” — and on performers including Dylan.

“I got to know [Smith] roughly around that time in [New York’s] the Village, I would see him bustling around. What the Anthology did was broaden my horizons. I had never heard any Cajun music before that, shape-note singing, other stuff like that. So I owe everything to him. He was so before his time.”

Cohn worked as the consultant for the 1997 reissue of the set, on Smithsonian-Folkways.

Although Sony and other major labels drastically slowed down their reissues of early material, Cohn still works with other reissue projects, including a 2019 set It’s the Best Stuff Yet on Frog Records, which features considerable unissued material from Blind Willie McTell’s last session in 1956. There are still nuggets out there…