Don’t let a century’s worth of pop culture fool you — the best of the best barbershop quartets have five voices.

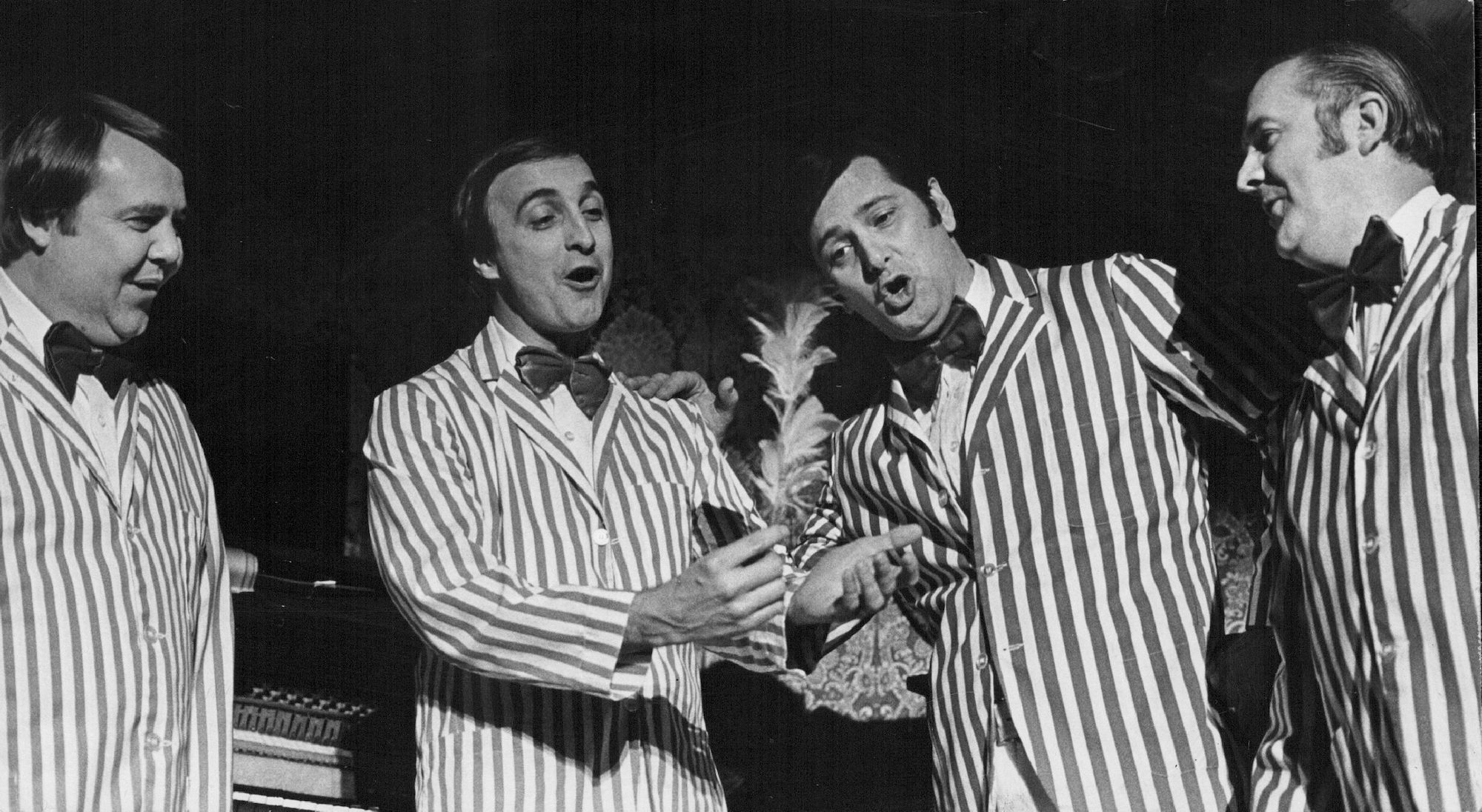

Sure, four striped-shirt, straw-hatted, bow-tied bodies — but five voices. The second tenor sets the stage with a lead melody line, which the first tenor lays a high harmony on. The baritone singer handles mid-range, while the bass, the deepest voice of the four, lays a solid foundation. But when the overtones of these four pitch-perfect voices unite and merge, an invisible fifth voice emerges from the ether, an everywhere-but-nowhere aural apparition not unlike the effect of Buddhist monks chanting in a massive ancient temple. This unified fifth-voice phenomenon is known as harmonic coincidence, though it is nowhere near a coincidence, accident or fluke.

Summoning what former Barbershop Harmony Society President Art Merrill calls, “the voice of the angels,” takes well more than four peppy singers with dreamy voices. In fact, should one of the four mortals as much as drift off-pitch, the heavenly house of cards drops.

Harmonic coincidence can’t even be reproduced using keyboard-based instruments because of intonation flaws of the equal-tempered scale used to tune them. Accessing the great audible beyond requires a type of sonic geometry present only in certain sung chords known as ringing chords. One of them has earned the name barbershop seventh, or super-seventh, meaning a chord containing notes with exact frequency ratios of 4–5–6–7.

We don’t know what the hell any of this means either, but it’s true!

When four justly tuned human voices sing a super-seventh, minimal harmonic dissonance occurs, overtones bolster overtones, equal harmonic richness occurs, and sound can feel 3-D. Merrill describes what resembles an audio hologram with a physical effect, telling listeners, “you can’t mistake it, the signs are clear. The overtones will ring in your ears, you’ll experience a spinal shiver. Bumps will stand out on your arms. You’ll raise a trifle in your seat.”

Barbershop fans call this sensation seventh heaven and once experienced, it’s hard to forget.

Would you like a shave with that performance?

Both the genre name “barbershop” and roughly, the musical style itself, are thought to have originated in the non-angelic shave shops of 17th century England, where barbers were known to keep a stringed lute for waiting customers to tinker with, strums of which often sparked improv group songs from patrons.

Rather than ask for peace to steady their straight razors, bored barbers typically initiated call-and-response sing-alongs. Visitors who were aware of the fact they couldn’t sing, dropped coins into candlesticks to cover and shake tambourine-style, while others, fresh from the alehouse, slapped knees and stomped feet. The resulting squall was what Britons of the era called “barber’s music,” though these sessions were far from seventh heaven.

Southern comfort

American barbershop music, the intelligible and carefully arranged kind, has its roots in the late 19th century South, born from an African-American population with a rich cultural tradition of four-part hymns and folk songs.

After the abolition of slavery, harmony singing grew popular among men in social parlors (known as “cracking a chord”), as well as on street corners (referred to as “curbstone harmony”). The vocal pastime soon became commonplace in Southern barbershops, the local social centers of the era. Undoubtedly, the seventh heaven sound was summoned here and there, likely without an idea of what was actually happening. In Four Parts, No Waiting: A Social History of American Barbershop, genre historian Gage Averill reports that it was another 40 years until barbershoppers began to “self-consciously tune their dominant seventh and tonic chord to maximize a ringing sound rich in harmonics.”

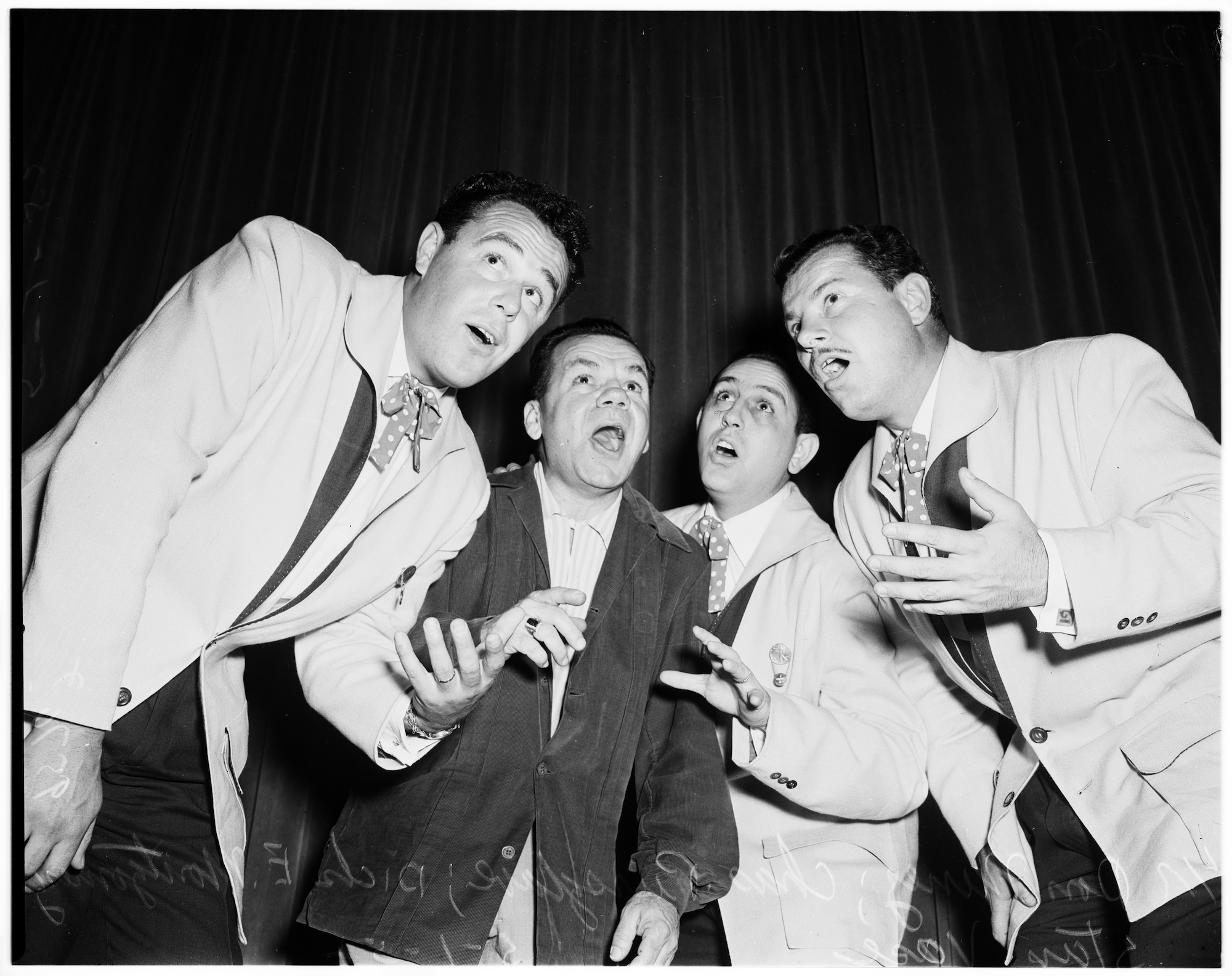

The earliest mention of barbershop style by name occurs in the same era, as used to describe the music of Southern quartets The Hamtown Students and The American Four. These two quartets are early pioneers of vocal stunt techniques used to warp the presentation of harmonies, including the “swipe” and “snake” maneuvers, both of which provide an auditory vision of melodies being painted in cursive.

It was the 1910 song “Play That Barbershop Chord,” however, that brought the style to the masses. As pianos became prevalent in middle-class American homes, sheet music for that tune and many similar were written and sold to no end, and over the next 25 years, barbershop music became a verifiable, if oversimplified, national fad.

The ABCs of barbershop quartets

In 1938, true barbershop finally found its forever home when a pair of stone-cold hustlers by the names of O. C. Cash and Rupert Hall randomly struck up a conversation in the lobby of Kansas City’s historic Muehlebach Hotel. Both happened to be huge fans of formal, concert vocal music, and deeply averse to the watering-down of traditional barbershop composition. Once it was realized they both lived in Tulsa, the two pledged to recruit like-minded Oklahomans to stand for the love of the art.

With a proclamation signed “Rupert Hall, Royal Keeper of the Minor Keys,” and “O. C. Cash, Third Temporary Assistant Vice Chairman,” the two established the “Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America” (an entity known to the IRS as SPEBSQSA Inc.). The first meeting, a barbershop concert with speeches, took place in April 1938 on a hotel roof in Tulsa and was attended by roughly two dozen onlookers. The second meeting, held a week later, drew 70 guests…and a growing number of complaints from hotel guests.

By the third SPEBSQSA meeting a month later, the crowd had somehow grown to nearly two hundred attendees and singers, producing such noise and spectacle on the roof that a traffic jam formed around the hotel. A Tulsa newspaper reporter walking by smelled a story and scaled the steps, in search of the event’s organizers. When found and asked for details, Cash swung for the fences, blasting the decline of “true barbershop” and declaring SPEBSQSA a national organization, before providing the reporter contact info of several unaware friends across the South, which he identified as “department heads.”

Cash’s showmanship made the resulting story a hit on the national newswire, scoring SPEBSQSA press across America while earning Cash’s “department heads” countless random calls from barbershop fans looking to study and sing.

The great rift

Eighty-plus years and one huge name trim later, the Barbershop Harmony Society has over 22,000 members, though not all in harmony. Efforts by the group to modernize have led to a flood of younger members eager to barbershop their favorite pop songs, drawing heat from old school members who cite Cash and Hall’s original mission to preserve the style formally, all technicalities in place. Former BHS chief executive Ed Watson draws the line, explaining: “They call us Kibbers, as in ‘Keep it Barbershop;’ then they are the Libbers, which is the liberal interpretation of barbershop.”

Hardest-core of the Kibbers are the 300-member subset of BHS known as the Barbershop Quartet Preservation Association, and they are not amused in the least. Averill reports that arrangers within the sect, which holds its own convention and meetings, firmly “believe that a song should contain anywhere from 35 to 60 percent dominant seventh chords to sound barbershop,” a qualifier most every contemporary radio hit fails to meet.

The Barberpole Cat songbook, a 10-number barbershop hymnal members study for easy performance with new friends at concerts and global conventions, easily meets this requirement, though it’s less than a smash with the youngsters.

The BQPA does present an entirely legitimate argument though, one based on much more than sentiment: pop song chord structures aren’t built for barbershop harmonizing. Being that most are written using simple blues progressions, with next to no super-seventh chords, opportunities to achieve seventh heaven severely diminish when barbershopping modern pop. Four-part arrangements of Katy Perry and Drake songs can make for beautiful harmonies, but preserving the hallowed fifth voice depends on keeping ringing chords like the barbershop seventh alive.