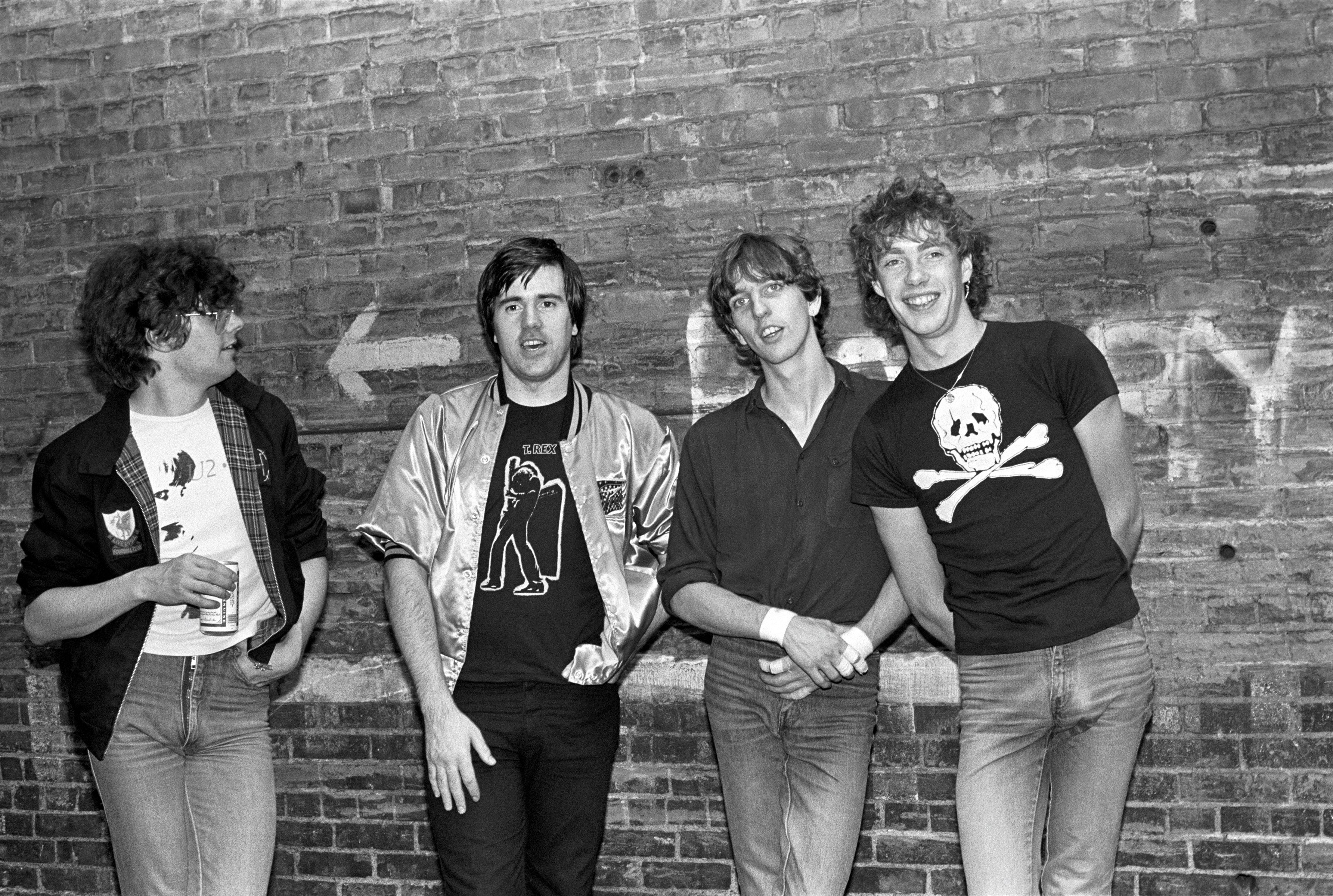

When they were starting out in the late ‘70s, legendary Irish punk band Stiff Little Fingers sent out their promo cassettes to record companies made up to look like a bomb. “Some people really didn’t get it,” original Stiff Little Fingers member Jake Burns says. “The first single was called ‘Suspect Device,’” he explains. “So it was kind of a no-brainer.”

To this day, the realistic-looking bomb cassette may be one of the most authentically punk maneuvers in music history, and completely inappropriately appropriate for one of the most influential punk bands of all time.

Founded in 1977’s battle-weary Belfast, singer and guitarist Burns is keeping the band going nearly four-and-a-half decades later, due, in large part, to their never-waning, well-earned fans. From Green Day to Nirvana, there’s a reason SLF’s consistently being cited as a “favorite” or “greatest influence.” Quite simply, SLF defines punk, both then and now.

“I guess we underestimated how inured to the everyday violence we had become as we thought it was kinda funny,” Burns says of the bomb cassette controversy. “I mean, bad-taste funny for sure, but funny nonetheless. Sadly, some labels didn’t see it that way and there was a great apocryphal story about one ending up in a bucket of water. Even years later, I found out that some guy who ended up working with us when we were at Chrysalis had thought we were ‘wankers’ for sending this out because he’d been evacuated from an Oxford St. store at Christmas due to a suspected bomb. A bomb scare. That was a minor inconvenience for us and this guy harbored that resentment against us for years.”

We spoke with Burns about all things SLF, from the band’s beginnings, their plans for touring, and why more punk rock is what the world needs now.

SPIN: What was it like growing up in Belfast during the Troubles?

Jake Burns: That’s a difficult question to answer, simply because I didn’t have anything to compare it to. So, to me, it was just “growing up.” We would have occasional holidays to the Republic of Ireland and to visit family on the U.K. mainland, but they were such short periods of time that the difference didn’t really register on me. Apart from one time when we were returning on a ferry and in those pre-internet days, the boat couldn’t pick up a television signal until you were within range of port. So, we were coming down Belfast Lough and the TV was suddenly filled with pictures of Belfast city center on fire. It was referred to as Bloody Friday by the media as the IRA detonated over twenty bombs in town in the space of about an hour and a half. That brought the difference into a sharp focus.

In general, however, the main memory is one of boredom. Because of the unrest, bands wouldn’t or couldn’t come and play, the center of town was ringed by security gates that were shut after 6:00 p.m. and so became a no-go area, people stayed in their own sections of town and any trip to say a local bar was always accompanied by a sense of unease if someone you didn’t recognize was there. The threat of bombing, no matter how unlikely, was always real.

What is Belfast like today? Are the Troubles really over?

I haven’t lived in Belfast since 1978, but I try to get back at least once a year, usually when SLF are playing. The city is now a normal, vibrant, fun European city. It’s become known as a party town, which considering the restrictions its people lived under for so long is not terribly surprising. Having said that, all through the Troubles there was always a great sense of humor about the place. You either laugh or you cry, I guess. But there is a resilience about the people, for sure.

As to whether the Troubles are “really” over? I couldn’t say. The divide between the people goes back centuries and you can’t fix a bullet wound with a Band-Aid, but certainly things have been moving in the right direction for many years now and I don’t think anyone wants to see a return to the days of the early ’70s.

Tell us about your pre-SLF band Highway Star? What inspired you guys?

I first wanted a guitar and to play when I was about 12 years old and saw Rory Gallagher playing with his band Taste on local TV. Prior to that, I’d been like most young kids when it came to pop music, I liked what was in the chart. I was particularly a big fan of Motown records. It seemed like most of my collection, such as it was then, was on that label. However, seeing, and more importantly “hearing” Taste changed my world. That guitar tone literally stopped me in my tracks. I really mean that, I was walking out of the room when they started playing “Morning Sun” and I froze. “What WAS that? And how is he doing it?” I sat back down and within ten minutes or so had decided that I wanted to “be” Rory Gallagher!

I mentioned that I was about 12 years old, but most of my friends were a couple of years older than me and were into what was referred to as “underground” music at the time, so I was listening to Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Jethro Tull, etc., while my real contemporaries were living on a diet of T.Rex, Gary Glitter, etc., which I considered “kid’s music.” LOL.

How did Highway Star discover punk?

By the time punk happened in the U.K., I’d become bored with the endless guitar solos of what was now known as metal. The tiresome sagas of prog-rock really got me down. And I’d started paying more attention to the actual songwriting, rather than the flash presentation. That led me to what were known, rather dismissively, as “pub rock bands.” I loved the visceral excitement of Dr. Feelgood and Eddie and the Hot Rods. And, I particularly admired the songwriting of Graham Parker. Then, the punk bands arrived. I loved the brashness and the attitude. But, I couldn’t see any long term to it all. It felt like each band had a three-minute “Fuck You!” to deliver and they did so with real gusto. I just couldn’t see where it went from the initial burst of energy. Then, I heard the Clash. And the songwriting shone through. Mainly the lyrics. A song like “Career Opportunities” really hit home. This wasn’t about bowling down Californian highways or the Knights of the frigging Round Table. It wasn’t even a call for “anarchy.” It was a howl of well-expressed rage about how a generation was being abandoned to the dole queue, and living in N. Ireland where the unemployment figures were one in three, that really hit home.

How was your music received in the Belfast of the ’70s?

When we started trying to play, there were only about three venues you could aim for, and they all seemed out of our reach. There was the Ulster Hall, which was for large touring bands, of which a few now deemed it worth the journey, mainly punk bands it has to be said. So, you could hope for a support slot there. The university, ditto. Although they did have a couple of venues within the campus that local bands could comfortably fill, it was still out of our range. And The Pound Club, which was the preserve of local bands playing Eagles and Van Morrison covers. The problems we faced were two-fold, well threefold if you count the fact that we weren’t very good! One: audiences and bookers expected you to play covers. Now, even though we had learned an impressive set of punk covers, that wasn’t the sort of cover they meant. They wanted the afore-mentioned Van and Eagles fare. So, we had to get someone to believe us that there was actually a market for punk rock and then try to slip our one or two originals into the set, if and when we got a gig. Two: Punk was being vilified all across the mainstream media at the time. It was violent, nasty, without merit etc. And the last thing any venue wanted, especially in a country that had been riddled with violence for years was a “violent” musical form.

However, there were a couple of other bands in Belfast who were ploughing the same furrow as ourselves, Rudi and the Outcasts. And these guys had discovered a smart wrinkle in the booking scenario. They found that if you booked a venue yourself, typically a function room at a hotel say, you could claim it was a friend’s 18th birthday party or such and that you could then have a band playing. The band, of course, being yourselves! All you then had to do was spread the word and stand in the car park pre-show selling “party invites” and hey presto! A gig! We appropriated this idea and did the same.

Why was punk important?

I think it was initially important for the reasons I touched on in a previous answer. The bands of the time had gotten bloated. I don’t mean that in a financial sense, although undoubtedly some of them had, and had consequently lost touch with their audience. I mean what had shows about King Arthur on Ice or Greg Lake insisting he could only play while standing on a fucking Persian rug have to do with Little Richard?

Punk felt to me like the closest I could ever get to seeing Elvis Presley in 1956. It was a re-establishment with rock’s roots. The snotty little kids taking it back. Making it dangerous again. And, I honestly believe, it helped bring back the classic pop song. Some of those records may not sound like that today, but a huge number of them had great melodies and ideas in there. And they all came in under or around three minutes.

What inspired your early songwriting?

I just wanted to write exciting songs. Before we met Gordon Ogilvie, who became our manager and my main songwriting partner, I was writing about anything that came to mind. Not just the usual “punk fare” of my boring job (“Breakout”) but also my life in Northern Ireland (“State of Emergency”). It was Gordon who really concentrated my efforts with regard to subject matter. And it was simply advice that I’d been given years before by my school English teacher: “Write about what you know.” Over time, that expanded to be: “Write about things that concern you. Or about things you’d like to see change.” That’s still my main driving inspiration today. I know that sounds a bit po-faced, but hopefully I’ve done it with a sense of humor and always a sense of hope. It’s all too easy to write that sort of song and it sounds like “Woe is me. Everything is terrible.” I like to think that while that might be what drove me to pick up a pen and a guitar, the end product always has some form of hope to it. Sort of: “Yes, things are rough, but they don’t have to be if you want to change them.”

Why did the band split in 1982 — and why did you get back together?

The mood of the times in 1982 was moving against the band. As I said, one of my early motivations was to kick against the “King Arthur on Ice” style rock show. That total divorce from most of the audience’s reality. By 1982, Duran Duran and the like were making videos on luxury yachts in the Caribbean and the mighty synthesizer was everywhere. Gritty guitar bands were not really on the agenda. Now, I have nothing against rock music as entertainment. Escapism is a fine thing, it’s just not my thing. Also, we as people, were not the folks we had been when we formed the band. Cracks were appearing and arguments became more and more divisive. Add to that the fact that our audience was dwindling, as I said we simply weren’t flavor of the month anymore, and splitting up seemed like a wise move.

So, we went our separate ways and tried various different musical ventures. None of which set the world on fire. And, being honest, none of which were as satisfying as SLF had been. So, when Ali and I re-established contact some four or five years later, re-forming felt pretty natural. I’ve also said many times, it was also because we were broke! The prospect of a run of shows, finishing in Belfast just before Christmas, giving us a bit of spending money in our pockets and the chance to spend the holiday with our families was too good to turn down.

In all your years of playing live, what gig were you most well-received?

There are many. Although, as a band, we never achieved U2 or Bruce Springsteen status, our audience is immensely loyal and partisan. But, two venues stand out. Glasgow Barrowland, which has become so inextricably linked with us that it really feels like a spiritual home, if such a thing exists. The first time we played there on the reunion tour. We had to add a matinee show as demand for the tickets was so huge. Walking onto that stage, to that deafening roar was really special. And Belfast in 2017 at Custom House Square. We wanted to mark the 40th anniversary of the band with something special in our hometown. We’d looked into the possibility of doing a free concert in the city, but it turns out to do a “free” concert on the scale we were proposing actually costs around £200,000 [$260,000]. So that idea bit the dust! But we pulled together a show with some good friends from over the years, The Stranglers, Ruts DC and the aforementioned Outcasts, our compatriots from way back in the day. Once again, walking out that night, in front of 5,000 people in my hometown to a wonderful welcome is something I’ll remember for the rest of my days. If that sounds emotional and “sappy”, I don’t apologize for that one bit!

How does it feel to be an inspiration for so many bands (namely Green Day and Nirvana)?

It’s very flattering when any musician says that you have been an inspiration to them. I still remember how I felt all those years ago when I first heard Rory Gallagher and to think that our band had that effect on folks who went on to become musicians in their own right is very humbling.

How do you feel about Dropkick Murphys covering “Suspect Device”?

Much the same as I said, it’s very flattering when people care enough about what you’ve done to want to do it themselves. I’ve spent a lot of time with the Murphys lads, both on my own and with SLF, so it’s difficult to separate my feelings for them as people from what they actually do. Suffice to say I’m very fond of them on both levels.

What musical instrument do you wish you’d mastered?

Piano. I can play a little bit. Self-taught, so probably full of the same mistakes I make when playing guitar. But, to hear someone like Albert Ammons or Meade Lux Lewis play is just wonderful. I’d love to be able to master just basic boogie-woogie piano. It’s such a joyous noise.

Is punk relevant today?

As long as the songs are relevant, then the form is relevant. If the writer writes about something he or she cares about and conveys that passion, then it’s relevant. It doesn’t matter if it’s a punk song, or rap, or classic rock or a pop song. It’s all down to intent and content.

Is there a vibrant punk scene anywhere right now?

I’m really not the person to ask regarding that. I’ve become a real “stay at home” guy. Unless we’re touring, something no-one has obviously been able to do this year, then I’m not really exposed to much. I’m of two minds as to whether that’s a bad thing. People have said to me that they think it is. But then I once read a quote from an Irish novelist who said she didn’t read much new fiction because: “If you read rubbish, you might be tempted to write it.” Now, I’m not saying all modern punk music is rubbish, of course it’s not. But, I’ve probably heard “all the moves,” so it doesn’t excite me as much as it used to. And, the novelist’s quote is definitely pertinent when it comes to songwriting structure. If you listen to too many of the obvious chord changes, you’re likely to think it’s ok to fall back into that pattern. And I did all that 40 years ago!

Who were the best punk artists of the past and who does it great today?

Punk was such a broad church when we started. It encompassed everyone from the Sex Pistols, the Damned, the Clash, Ramones to Talking Heads, Elvis Costello, Blondie, Devo. There was room for a lot of differing styles. It was more about the attitude. Then, around 1982 or so when, as I said earlier, the synthesizer started rearing its all-pervasive head, punk became insular. It became more about the number and position of metal studs on your leather jacket. It became more about the height of the spikes on your Mohican haircut than any concern about the songs. It became ugly. And I lost interest.

I think someone like Costello has always remained interesting, simply because he hasn’t stood still. He’s raced around all over the musical map indulging every musical itch he’s ever had. And it must be marvelous to have that sense of freedom. I’m simply not talented enough to indulge myself in various styles.

Again, as I said, I have always loved “pop” songs, so those bands that have a strong sense of melody have always appealed to me. And, if they can ally that with a sense of social justice and integrity, then I’m bound to pay attention. So, a band like Bad Religion always get my time.

After over 40 years, what are your hopes and plans for the band going forward?

Like everyone, my immediate concern is for this pandemic to be overcome and for us all to be able to safely get back to work and some sort of normal as soon as possible.

Obviously, at this stage of my life (I’m 62), retirement gets mentioned. It’s not something I’ve really thought of. I guess as long as I feel reasonably “youthful” (and I still foolishly do, even if my knees occasionally tell me otherwise) and as long as there’s an audience for what we do, and we still enjoy what we do…then we’ll keep doing it. So, a 50th Anniversary Tour in the future? Never say never, I guess.