THE SONGS

Shelley: A lot of the story behind “Tunic” is inspired by the movie Superstar by Todd Haynes that he made with Barbie dolls. That was a big movie for us. You couldn’t see it legally. Todd would screen it around or you could buy a videotape at See Hear in Manhattan.

Ranaldo: I think Karen [Carpenter] really wanted to bust out sometimes but was framed in this cutesy pop sensibility. As you know, she was anorexic and had all these other issues going on. She was definitely a tortured person, and there was something so beautiful about her singing and the way she played the drums and sang. It was very unusual.

Gordon: It was Thurston who turned me onto how beautiful Karen’s voice was actually in their songs. Then we rented a video of their videos, the Carpenters videos, which are all really weird and creepy. I just became so fascinated with how her voice was so soulful and actually beautiful, away from the context of them being seen as part of the establishment and conservative during a time when music was representing the sound of rebellion. Then I started thinking about how basically women started feeling like we only have control over our bodies, but we don’t even have that anymore. The fact was that, tragically, she wanted to make herself disappear.

Also Read

Devon Ross Feels the Noise

Ranaldo: For “Mote,” the lyrics were inspired by this poem by Sylvia Plath called “The Eye Mote.” I can’t quote it offhand but I was really affected by it. I just got started and began free-associating off the imagery I picked up out of the poem, and I dunno, just kind of made it my own in a way. It’s been really heartening to see how popular the song has been over the years, a favorite of a lot of fans. It’s always a super fun one to play, especially with that crazy long ending.

Gordon: “My Friend Goo” emerged from Raymond Pettibon’s Sir Drone. It started out as this punk rock story, and then it was all about haircuts. And then Goo was this girlfriend of one of the two characters who hung out. And so by default she became the drummer. I thought it would be funny to just hold her up in a way.

Moore: For “Titanium Exposé,” I wanted to write a straight-ahead urban love song. and when I say urban I mean I always love ideas about two people living within their means. Artists in a place of poverty, but you’re completely enriched by the creative connection you have. And then Kim sings the refrain from LL Cool J’s “Jingling Baby,” where he’s talking about the big gold earrings on hip-hop girls’ ears that would jingle. We were really into LL Cool J at the time, so that’s where I remember that song coming from as well as “Kool Thing,” which is based on Kim’s infamous interview with LL in SPIN.

Gordon: I don’t know how much LL was aware of us, but it was really cool of him to do it. I really loved Radio and I was curious about how much of Rick Rubin’s aesthetic wrapped up on him and what kind of rock music he liked. I was really disappointed to learn that he was into Bon Jovi [Laughs.] The video for “Kool Thing” was actually super based on “Going Back to Cali.” I love that video, it’s so great. I started interviewing people in front of CBGB, just a scene of white kids, and I’d ask them ‘What do you think of LL’s record?’ and I treated it like this sociological experiment or something.

Moore: I had the idea for the ‘Disappearer’ 12-inch cover from seeing that image in some magazine. I thought, here’s somebody who had completely gone through this really challenging period of being a young woman in an industry that was so demeaning, but somebody who was rising above it and changing to become her own dignified self. All of a sudden there’s this photo where she was not on the set of an X-rated movie but actually looked like a woman who was going to survive this thing. I liked how it fit with the idea of “Disappearer.” A lot of that song has to do with these signs and your ability to control them; don’t let people tell you who you are no matter what. That to me was interesting in the respect of seeing this photo and putting a halo over Traci Lords’ head to make her look saintly. The art director sent it to whatever management she had, and she said to us, “This is so cool. Thank you.” She was really sort of touched by this picture that had her with a halo over her head.

THE COVER ART

Ranaldo: We had enthusiasms and we wanted to share them, and one way to do that was put up different artists on our covers from Daydream Nation with Gerhard Richter to Raymond and then Mike Kelley for Dirty and then Richard Prince and whoever else we used for covers. We were all really involved in what was going on in the art world and of course the culture world, talking about books, talking about films. And we wanted all that to be evident somehow in our work.

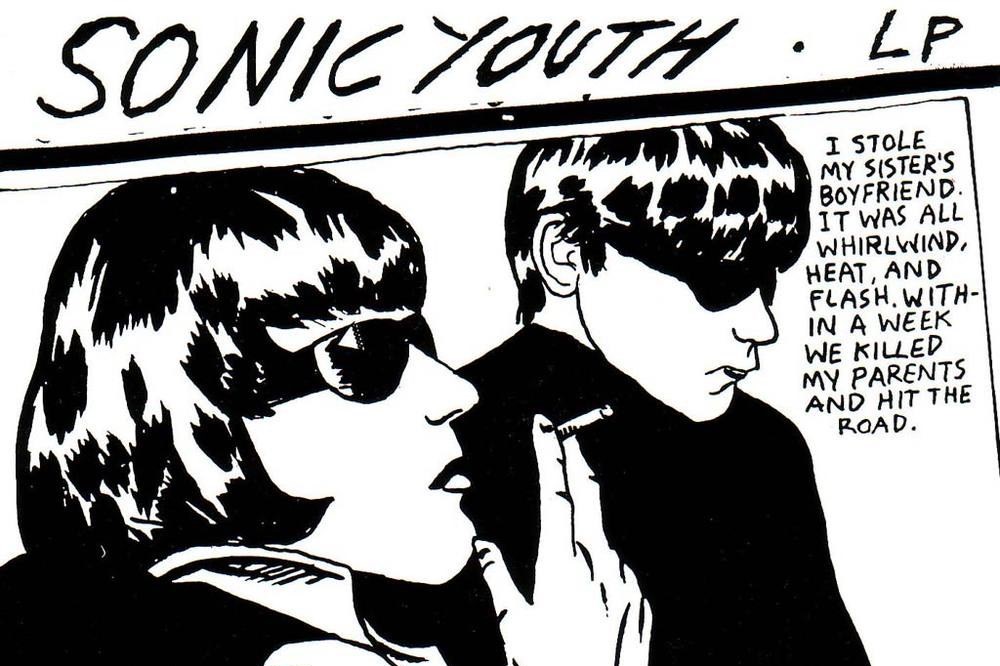

Raymond Pettibon, Goo cover artist: I had this True Detective magazine, and I saw that picture on the back cover. At the time I didn’t know it was a depiction of the Moors Murders in England. That didn’t register with me because I wasn’t a true-crime aficionado like I am now. It was pretty much a reasonable facsimile of that magazine’s back cover and the photo of David Smith and Maura Hindley. I think the dialogue was the same as well. Usually, I change quite a bit. I have sources from life but mainly reading and art.

Shelley: I didn’t know about the context of his drawing. I knew about the Moors Murders because we had spent a lot of time in England and we drove through that part of the country. And we did hear those stories in our travels. But when we first saw the original photo, I was blown away.

Moore: I had seen the original news photo that Raymond drew from, and I just thought there was something very evocative about this image where you could weave different narratives into it.

Gordon: It’s so funny, our record company and our A&R guy were totally against it from the beginning, almost strictly from the point of view of it being black and white. Then they wanted to put the parental advisory sticker on it, because Tipper Gore is coming out against swear words and language.

Ranaldo: That wasn’t the original image of Raymond’s that we chose for the cover of the record. It was this black and white drawing of Joan Crawford with her big face and these huge red lips. And under it said ‘Blowjob?’ with a question mark. We wanted that to be our cover and were gonna call the record Blowjob? because it was, like, our first sellout record on a major label. The people at Geffen, even though we had contractual control over what we put out, begged us to do another cover, like ‘Please don’t do this to us!’ So we were like, alright. And then we chose something that became even more iconic.

Moore: Those Pettibon images [inner sleeve photos] I basically Xeroxed out of one of his books. I had all of his art and fanzines, hundreds of them. They go for hundreds of dollars now, but they were 50 cents each when I got them. So I found two images I thought would be really cool and just laid it out like that. The guy who was doing the design for us at Geffen looked at the layouts for the cover where I did all the scotch taping and he would see one of my hairs and a dirty thumbprint or something. I was like, “Don’t get rid of that. Leave it as it is.”

Ranaldo: There’s like a million mashups and takeoffs of that cover, like Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie or Jerry Seinfeld and George Costanza. We are actually going to try and collect them in a book.

Shelley: Before the pandemic happened we had a number of things we were thinking about for the anniversary of Goo. And then all sorts of things went to the side as our priorities changed. But one of them was a book filled with what we call Goo mashups. We will see if we get it out this year.

Pettibon: That cover took on a life of its own with other people and appropriations. When something is done, I just leave it alone. But there is no escaping Goo. All the parodies of it are amazing. Every time I see them it really tickles me.