One morning in late in the fall of 1988, I was walking through New York City on my way to work when I popped a cassette into my Sony Walkman. It was a bootleg recording of DJ Red Alert’s hip-hop show on 98.7 FM in New York, then known as KISS-FM (which moved to 97.1 and became the iconic Hot 97). Because I had to be at work at 9 am and couldn’t stay up late enough to listen to Red Alert, I would start recording on a boom box with the volume turned down and in the morning, discover new records in what was then still an emerging new sound: hip-hop. This particular morning, one song sent shockwaves through my headphones: it was “Fuck Tha Police,” by a then little known group called N.W.A. The rest of their story is well-known by now.

A sonic pipe bomb, the song stopped me in my tracks. I couldn’t quite wrap my head around exactly what I was hearing. But a few things were obvious: N.W.A. had an audacious wicked charm. The music was bombastic, vicious, revolutionary and sick in both senses of the word.

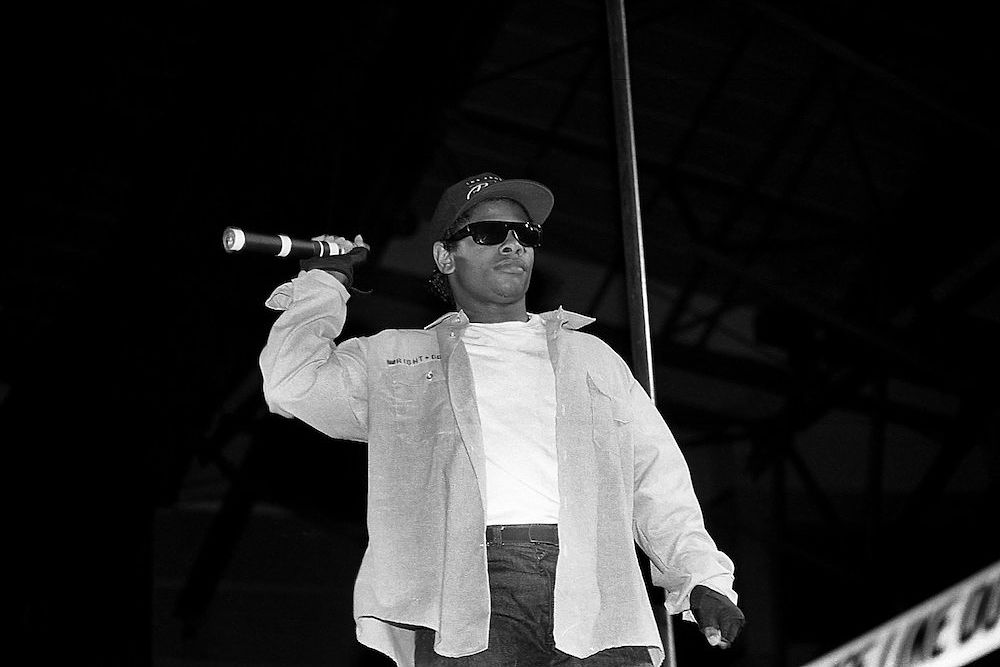

When Eazy-E died due to complications of AIDS 25 years ago on March 26, 1995, he left behind a wife, seven children and an outsized impact on our musical landscape. Four weeks earlier, he had checked into the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles with what he thought was asthma. At the time of his death, AIDS was still too often associated with gay sex or needle sharing. On March 16, when Eazy released a statement to the press announcing he had AIDS, the hip-hop community got a reality check almost as shocking as the one Magic Johnson had delivered to the sports world four years earlier.

Having started his professional life as a drug dealer, Eazy segued into rapping and then running his own label, Ruthless Records. Though he wasn’t the star rapper of N.W.A, he did have skills and parlayed that into a successful solo career. (His 1988 solo album, Eazy Duz It, sold 2.5 million copies. In 1992, he released 5150 Home 4 tha Sick, an EP that sold 500,000 copies. The following year he dropped It’s On (Dr. Dre) 187um Killa, an EP-length attack against his former collaborator which sold more than 1.5 million copies.)

Also Read

The Top 50 Hip-Hop Singles Of The 1980s

His voice was high, thin, reedy, nasal, drawling, and defiant. His lyrics may not read today as brilliant poetry but they’re still evocative if frequently offensive, as in these lines from “Gangsta Gangsta”:

Well, I’m Eazy-E, the one they’re talkin’ about

N***a tried to roll the dice and just crapped out

Police tried to roll, so it’s time to go

I creeped away real slow and jumped in the six-fo’

With the diamond in the back, sun-roof top

Diggin’ the scene with the gangsta lean

‘Cause I’m the E, I don’t slang or bang

I just smoke motherfuckers like it ain’t no thang

And all you bitches, you know I’m talkin’ to you

“We want to fuck you, Eazy,” I want to fuck you too

Restless, grim, and raunchy, Eazy’s persona was central to N.W.A’s identity at the time the group was defining the gangsta rap subgenre. Like professional wrestling, the spectacle was hard to turn away from. But N.W.A did much more than just shock the world with their gritty, violent and often misogynist portrayal of young black inner-city life on the west coast. For a large segment of white suburban kids, the group’s unlikely success made the gangsta ethos something aspirational. (N.W.A. also did the one other sure-fire thing to launch a pop music career: they drove parents nuts.)

Just to provide some context of what the music world was like in 1988: the No. 1 and No. 2 best-selling albums of that year were George Michael’s Faith and the soundtrack to Dirty Dancing, with each selling over 10 million copies. N.W.A. released Straight Outta Compton the same year, and with almost no major radio play and limited distribution (and despite censorship efforts by Tipper Gore’s Parents Music Resource Center), the album was a huge commercial success, selling almost three million copies and opening a shotgun blast-sized window into Compton for white America.

Jolting, almost nihilistically angry, Straight Outta Compton had a freedom and joyfulness to it. The music was a celebration of raw violence, boiling with frustration. N.W.A had an outlaw attitude so authentic that many listeners — soon to include the FBI — were hard-pressed to tell whether this gangsta stance was real or fiction.

While Eazy’s former bandmates, Ice Cube and Dr. Dre, went on to have far more mainstream success as solo artists, Eazy’s role in the transformation of American pop culture is hard to overstate. Cube stole the spotlight as a rapper, and Dre was the driving force behind the production, but the world might never have known about either of them had it not been for Eazy’s entrepreneurial genius. He was the man with the plan. Eazy was the one who corralled the group, arranged recording studio time, and had the expansive vision for NWA that went beyond selling CDs out of the trunks of cars. He had the drive and focus and access to funds, as well as the credibility to connect his friends from the streets with record industry professionals.

Eazy was less of an artistic visionary — after all, plenty of rappers before him had flaunted gang colors and a hood persona — as he was a marketing savant. But he could conjure harrowing depictions that mixed reality with fantasy and more than anyone else, Eazy-E was the first and most successful person responsible for packaging and selling gangsta rap to mainstream culture.

Rapper, producer, entrepreneur — he was many things, but a role model? Not so much. He dropped out of school in the 10th grade, posed with guns on album covers and he reveled in stories about cop-killing, drug-dealing, gang-banging and relentless virulent misogyny. In interviews, he usually defended all this as merely reporting the world around him. But after N.W.A. split, he held ugly grudges against Ice Cube and Dr. Dre. As a rapper, that was all too real.

And yet without support from radio stations or MTV, and under attack by politicians and law enforcement, Eazy still managed to steer N.W.A. from the streets to a position of not only great wealth but cultural dominance. He made Ruthless Records the top independent label in the industry and the largest black-owned indie since Berry Gordy’s legendary Motown Records. He turned hustlers into executives long before Puffy became Diddy. He was also attuned to the times. Remember, “Fuck Tha Police” didn’t blow up in a vacuum: it blew up in the context of the Rodney King beating, and the L.A. riots that accompanied the officer’s acquittal. Decades before Black Lives Matter, Eazy-E embodied the power and righteous anger of that movement in a way that was raw and thrillingly real.

Unlike Lil Xan or Lil Yachty or Lil Uzi Vert, the diminutive Eazy had one big thing going for him: powerful social commentary that resonated on the streets. When N.W.A’s musical Molotov cocktail erupted it left shards of meaning in your brain. Unlike the earnest Afrocentrism that immediately preceded N.W.A (Jungle Brothers and A Tribe Called Quest became instantly quaint overnight) or the more puritanical and strident political stance of Public Enemy, N.W.A’s rage was inseparable from the party.

N.W.A. isn’t the only group that owes a big debt of gratitude to Eazy-E. In late 1993, Eazy signed Bone Thugs N’ Harmony to Ruthless Records and served as executive producer on their breakthrough album E. 1999 Eternal (though he died before the group became massive stars). And while Eazy is now considered the Godfather of Gangsta Rap, he also played a key role in the career of one of pop music’s biggest names: long before “I Got A Feeling” was a staple of bar mitzvah playlists, Will.i.am of the Black Eyed Peas was another of Eazy-E’s proteges.

Eazy wasn’t easy. Beyond his disturbing lyrics, the man had his complications and contradictions. In the years after he became successful, he donated to Republican causes and even spoke out in support of one of the police officers involved in the Rodney King beating. Who the fuck knows what’s was going on in his head? But one thing is for sure. He lived like his music. With attitude.