This cover story originally appeared in the March 2000 issue of SPIN. We’re republishing it as Rage Against the Machine reunites for shows in 2020.

Nobody expected Mexico’s embattled presidente, Ernesto Zedillo, to bestow Rage Against the Machine with a sparkly key to the city. But as security is double-checked at Mexico City’s Sports Palace before the Los Angeles rap-rock agitators’ fall show, they receive an even testier greeting than anticipated. Addressed by a delegation of grim functionaries from Zedillo’s U.S.-backed Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the band is informed that they better watch their smart Yankee yaps onstage.

“The PRI said that if any artist [including the opening bands. L.A. rap-metal cranks Aztlan Underground and Mexican ska-punks Tijuana No] commented, in any way about the Mexican political situation, they’d be immediately expelled,” says Rage vocalist Zack de la Rocha, who set up the MTV-aired concert. “Here’s a party selling this democratic image to the U.S., but they want to silence anybody who criticizes them.”

De la Rocha—whose grandfather left Sonora, Mexico, for 20 years of migrant farmwork in northern California, and whose dad, Roberto (a.k.a. Beto), was an activist/artist in 1970s East L.A.—has been intently scrolling through his Mexican past to sketch his Chicano future in the four years since Rage’s last album, 1996’s Evil Empire. Embracing the indigenous Zapatismo cause, de la Rocha has traveled frequently to the southern state of Chiapas since the 1994 rebel uprising against government annexation of Mayan homelands. “It’s like going back and looking through my grandfather’s eyes,” he says. “I’d like to be a voice within the U.S. for people like him.”

De la Rocha invokes the ’94 New Year’s Day rebellion of the EZLN (Zapa-tista National Liberation Army) on the U2-ish opus “War Within a Breath,” from Rage’s latest, The Battle of Los Angeles (which sold two million copies in a month, after debuting atop the pop charts). He asks today’s Chicanos to check for the “lessons” of Chiapas and scalds the PRI, rapping that “their existence is a crime.” Now, with Rage set to play in a state-owned facility, President Zedillo is spitting back.

But the next night, as 5,000 kids jam a hangarlike pavilion at the Sports Palace, Zedillo gets the thunderous gas face. Middle fingers shoot skyward. EZLN flags wave, and deportation threats or not, the message is screamingly clear: PRI and U.S. governments, get the fuck out! Outside, ticketless young mexicanos shake metal gates and throw rocks before a busload of police arrive to spray them with fire extinguishers.

But as Rage wait in their trailer, the night’s loudest fuck-you is just barely audible over the buzzing crowd. A 10-minute video, projected stage-right, features a crew of Zapatistas—masked, armed, on horseback—riding into a jungle clearing, where a man dismounts and picks up a black electric guitar. Then, like a resolute but wittily ironic college professor, EZLN leader Subcomandante Marcos holds forth on the role of pop music—rap, metal, punk, ska, Rage Against the Machine—in the struggle for liberation. I don’t know which is more baffling: Marcos mimicking guitar-hero moves or the fact that kids in Korn, Che Guevara, and Guns N’ Roses T-shirts are peeping him, transfixed.

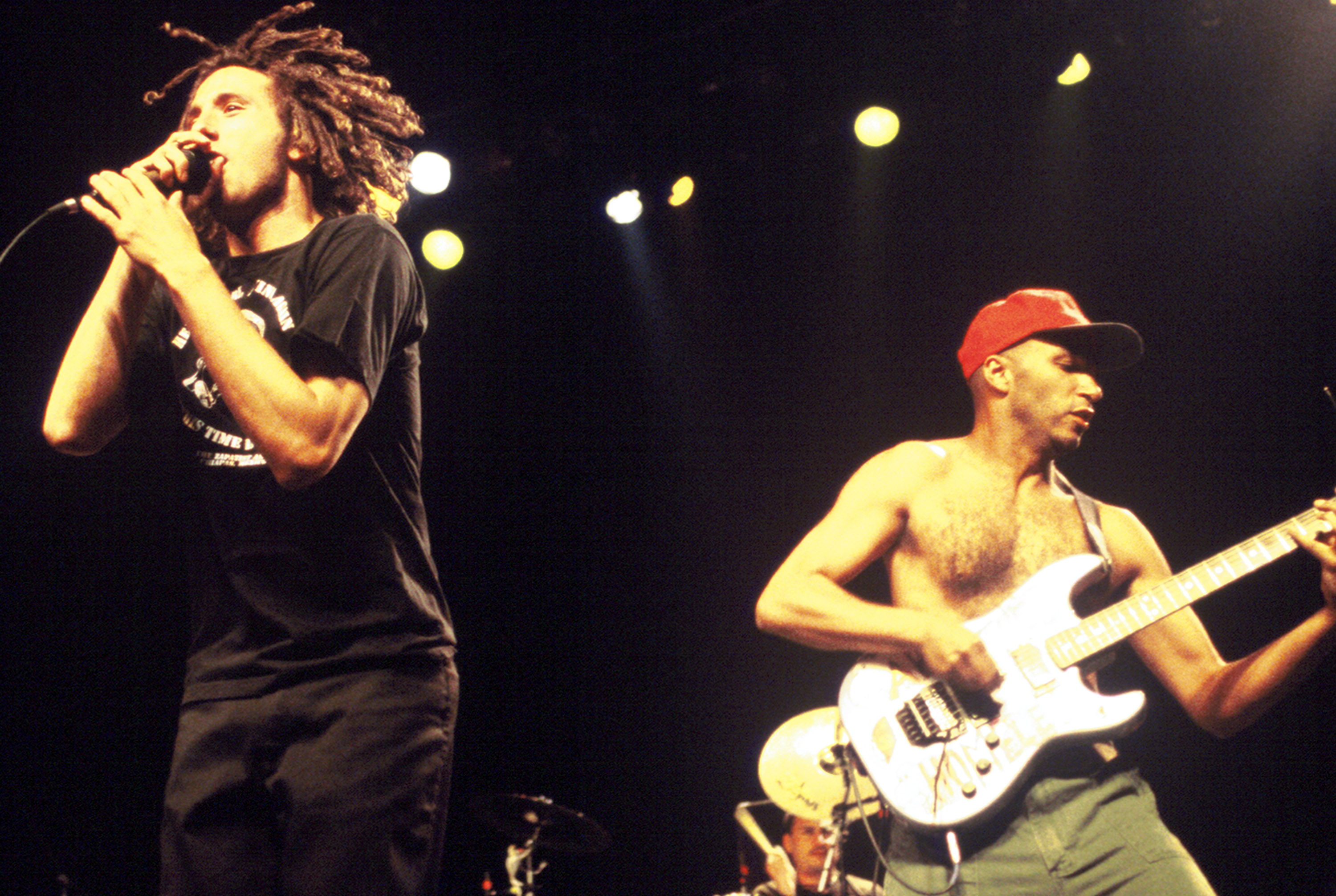

At this point, Rage could’ve whistled “This Land Is Your Land” and the roof would’ve blazed up. But when de la Rocha gives his usual intro in Spanish—”Buenos noches, nosotros estamos Rabia en Contra de la Máquina de Los Angeles, California“—and the band clicks into the new, rhythmically sprung “Testify,” the room flips into something beyond a brutish free-for-all. Energy passes between fans and band like an electrified crowd-surfer. De la Rocha, in camouflage baggies, stalks side to side, legs quivering, arms gesturing like an NBA point guard. Tim Commerford’s distorted bass jabs around drummer Brad Wilk’s tension-flexing breakbeats; guitarist Tom Morello sculpts feedback, flicks his toggle switch like a DJ on the fader, and stokes metallic chords with a hyper punk heartbeat. When the power blows more than an hour later, de la Rocha and Morello—Rage’s dueling mestizo voices—walk to the front of the stage, exhausted, fists raised. And while it’s not exactly John Carlos and Tommie Smith wrecking shop at the ’68 Mexico City Olympics, it isn’t empty posturing, either.

“Put it this way,” says Pacho Paredes, drummer for feisty rock en espanol collective Maldita Vecindad and a writer for left-leaning daily Reforma, “there are two ways of being modern, and the one to the south of the Rio Grande usually includes the experiences of the north, but rarely vice versa. Rage are the rare North American band that accepts the modernity south of the border: As a result, they’ve become part of that ‘other us,’ that extended us,’ that Mexican youth identify with.”

As Wilk says later, laughing, “When you connect that much with a crowd, it’s hard not to lose your mind.” The earnestly aw-shucks drummer chucked his kit at show’s end. “But seriously, we needed that: It was so rejuvenating. We realized how important we are to each other and how important the band can be.”

***

It’s telling that Rage Against the Machine had to go to Mexico to realize such a connection. In the U.S. both purists and cynics charge that Rage simply rehash fight-the-power platitudes for clueless white-jock consumers while clocking fat checks from Sony (as if this were an obvious get-rich-quick scheme). Newspapers and TV follow this cue, conducting mosh-pit exit polls, focusing on red-faced yobbos who hoot, “Hey man, I’m just here for the music!” But in a decade when teenage angst, and then lust, paid off well, Rage also won scores of disciples with a dizzying list of political causes, including reproductive rights; AIDS treatment; defense of Native American activist Leonard Peltier and African-American journalist/activist Mumia Abu-Jamal, both jailed in connection with deaths of law-enforcement officers; anti-sweatshop and anticensorship work; and various Amnesty International initiatives. The band’s musical program—set forth on 1992’s self-titled debut and Evil Empire, both multiplatinum—drowned these issues in a head rush of guitar effects and fever-pitched “militant poetry,” demanding a which-side-are-you-on? loyalty more common to Christian coalitions, the police, and the NRA.

But after doubting their own commitment (Empire was recorded amid rumored contractual pressure and ego-trippin’ spats), Rage are now moving into a more nuanced, more ambitiously contentious, realm. Rock politics in the years since the Vietnam War have usually meant philanthropic group hugs against faraway horrors (Live Aid) or vague “consciousness-raising” from bands who’d rather be rocking a party (Tibetan Freedom Concert); punk and hip-hop have confronted more systematic evils but lacked follow-through. Rage are trying to be a “political” band in a riskier, more comprehensive sense, pushing a history-conscious, integrated activism. In a global economy, if you’re arguing “free trade,” you’re also arguing sweatshops and the World Bank and unemployment and education and prison reform and alienated white boys.

As multinational employees with an ax to grind, Rage are shameless reformists, but how they go about it is still evolving. Morello, assured by Leaguer and defensive product of Illinois heavy-metal parking lots, has his stance: “I want to do political action, and I want to rock, no matter how flawed the contexts. Those are my concerns, and I’m willing to let the kind people at Epic/Sony take care of the record-company business.”

De la Rocha, the B-boy-punk dropout, has his: “Record companies are investment bankers lending us money: They’re not our artistic allies, and I don’t expect them to be.” Morello holds indie-punk “integrity” in contempt, respects hip-hop from an odd remove, and doesn’t believe that Sony, MTV, or Spin can color the band’s message. De la Rocha, however, sweats every distinction; he’s the warrior who worries that he’s failing to communicate.

“I’m not buying this bullshit line that says the situation in Chiapas or with Mumia or with the garment workers somehow has nothing to do with middle-class white kids at our shows,” he says. “Al! this alienation has roots; it’s not just TV or boredom or bad parents. And just because it’s getting expressed by, like, Timothy McVeigh or Columbine doesn’t mean we should throw up our hands.”

Facing down this dilemma, The Battle of Los Angeles is Rage’s great stage-dive forward. It depicts cities and suburbs, ghettos and malls, factories and fields, caught up in a constant power grab. And for the first time on a Rage album, it documents the “people” in these places (especially “Maria,” the Mexican illegal who sews jeans in a U.S. sweatshop). Morello’s riffs no longer reinvent basement bong hits; his twitchy jump-cuts map a freshly squalling landscape. Hip-hop’s boom-bap is assimilated into the rhythm section, like the MC5’s “Kick Out the Jams” backspinning on two turntables. Beats, bass lines, and guitar don’t tug-of-war for the spotlight; there’s actually space for de la Rocha to flow, plead, and give in to a little unguarded, grunge-era vulnerability. And ya know in the Beastie Boys‘ “Sabotage” when Yauch’s fuzzed-up bass line drives you to the edge of the cliff and Ad-Rock free-falls for all your sins? Rage do that about a half-dozen times here. The difference is that Rage ain’t winking.

Still, when de la Rocha chants, “All hell can’t stop us now!” on “Guerrilla Radio,” the first single from The Battle, you still wonder exactly what “us” he’s imagining. Although Rage, along with Run-D.M.C. and the Beastie Boys, spawned the rap-rockin’ mook caucus of Korn, Limp Bizkit, Eminem, Kid Rock, et al., they often sniff at this sort of rootless “nihilism” or “escapism,” ignoring the crossover with their own fans. And de la Rocha too heedlessly dismisses hip-hop culture’s money-makin’ component. Rage’s aborted tour with the anarchic Wu-Tang Clan in ’97 enlisted few black fans and revealed the headliner as rather predictable wonks by comparison. Unlike their heroes Bob Marley, the Clash, and Public Enemy, Rage aren’t leaders who were hurled up out of a musical scene or movement. And without one backing them, their protests could dry up like tears on a Backstreet fan.

***

In the 1979 film Over the Edge, Matt Dillon and a scruffy crew of teen outcasts rage against a sterile planned community by ignoring curfews, smoking pot, shooting guns, and pumping Cheap Trick. When city founders close their only refuge—a trashy, neglected rec center—suburban utopia explodes into a fiery pep rally. Zacarias de la Rocha, Timothy Commerford, Rob and Mark Haworth, and their extended “punk rock family,” never took a high school hostage, but they knew the urge.

Growing up in the late ’70s/early ’80s behind the Orange (County) curtain in Irvine, California, a 50-year “private urbanization” project once ranked as America’s “safest city,” was an advanced lesson in how the elite competes. Manicured lawns were mandatory; strip malls and bike paths were surreally immaculate. By 1983, the consortium of Irvine land developers was worth an estimated $1 billion, and they weren’t about to let any punk kids screw up property values.

“The place was so fucked,” says Rob “Cubby” Haworth, “that you’d feel bad for not driving a Jaguar to school.” Along with brother Mark, Cubby and Zack vented in the teen-punk band Hard Stance, releasing a seven-inch single; later, they became Inside Out, a popular touring hardcore band that recorded a scrappy Dischord-ant EP in 1990 (No Spiritual Surrender, still available via Revelation Records).

“We decided to play punk music to rebel against where we were,” continues Haworth. “[In Irvine], every house looked the same; cops were everywhere, pulling you over for the way you dressed or the color of your skin. Zack dealt with racial shit all the time. When Rage was first starting, he was going to junior college and still working 40 hours a week doing, like, social work with kids. I remember we went into a store once to buy a desk or something, and they were looking at him real nervous. Then they’re like, ‘Oh, we don’t make deliveries,’ trying to make us leave. I saw the effect that stuff had on Zack; it had an effect on me, too.”

De la Rocha was born in L.A.’s Lincoln Heights barrio, where his dad, Beto, was a member of Los Four, a visionary agit-art crew known for bombing graffiti, spray-painting murals, and crafting elaborate altars out of Chicano pop imagery. In 1974, the four were the first Chicanos exhibited in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; but Beto, a hands-on activist whose art explicitly stumped for barrio self-determination, felt far from validated. He hated hawking his artwork to white folks to subsist.

“I admired my father’s twisted resilience, in a way,” says de la Rocha, his usual rush of words slowing. “He struggled to break down the barriers between politics and art, which we struggle with. All the things he did with farm workers, with the anti-Vietnam War movement in East L.A., desegregating the art world, not letting his work be touched by commercialism. But at a certain point you have to face the gun of reality that’s pointing at you.”

Beto and Zack’s mom, Olivia, an Irish/German/Chicana grad student in anthropology, separated, and his father crumbled. “We had no money,” says Zack, “and my mother left school to support us. It was so unfair what he did to her, and what he did to himself; his work inspired me so much, but it’s, like, you gotta put food on the table.” Beto imprisoned himself for 40-day fasts and, on one of Zack’s weekend visits, destroyed more than half of his artwork, burning it in front of his son.

The de la Roches divorced in 1983; Olivia remarried, and Zack became a brown fly in the Irvine buttermilk. “We stopped speaking Spanish in the house,” he says (the root of his currently “pitiful” vocab en español). So he poured himself into music and anything else he could find.

“I call him the ‘Zack of all trades,'” says Commerford, 31, who has known de la Roche since fifth grade. “We played a lot of basketball, even though he was real small; we skateboarded all over. When I first met him at his house, he had this acoustic guitar, and he eventually taught me how to play the entire Sex Pistols album. We were in a band in seventh grade called Juvenile Expression. He was breakin’ at school when nobody else knew what hip-hop was. That kid was on it from Day One.”

Both boys fell face first into music “careers” during senior year of high school—de la Rocha got kicked out, and Commerford, refusing to cut his hair, quit the varsity football team to jam on Rush covers. “I was totally hung up on that Moving Pictures album,” he says, drolly. “I ended up working at Campus Gas, paying rent to my dad.” Commerford, the youngest of five kids, endured his own hectic home life; his mother developed brain cancer when he was seven (dying when he was 20). His father left her and remarried; at one point, Commerford lived with one of his sisters.

“I had no traditional upbringing of any sort,” he says. “Rage has been my upbringing. Zack is one of the few people still in my life who know my mom and who can talk to me about that time.”

Commerford is also one of the few people with whom de la Rocha talks intimately of his childhood, and in particular, of his dad. In the past, the Rage vocalist has denounced “autobiography” in lyrics, preferring to stick with broadside condemnations of power. But the cartoonish image of de la Rocha as full-time reader of the riot act transforms on the new album. Coming halfway into The Battle, “Born of a Broken Man” is the album’s stark centerpiece. Lit by an open-chorded, Nirvana-via-Beatles strum, the song snarls darkly before dole Roche speaks softly in the voice of a haunted son. He talks of a Jesus-like figure who “raped the spirit he was supposed to nurture” and slipped into delusions, “his thoughts like a thousand moths / Trapped in a lampshade.” While the martyr shakes and starves. Morello’s guitar scorches the ground beneath him and de In Rocha defiantly exclaims. “Never a broken man!” as if he’s finally able to look away from his father’s lifework turning to ash.

“I know how hard those words are for Zack to sing,” says Commerford. “They represent so much pain. But the fact that he put that out there makes me feel like we’re more of a band.” Given his dad’s trials (Beto is finally exhibiting again), you can understand why de la Rocha doesn’t romanticize DIY, get-in-the-van sacrifice. Suffering for your art is one thing; not saving your family is another.

De la Rocha is still thrashing out his own persona—passionate player, minus the shades-on, playa swagger. He’s like a fidgety kid who’s trying to juggle 20 cell-phone passions at once (the “tormented loner” image seems more hype than reality). Of course, I can’t really say, since the only time I actually sat down with the guy was for 30 or 40 minutes at a diner near his home in the middle-class, bohemian LA. enclave of Los Feliz. We had a lively talk, sharing jokes and outrages about everything wrong and right with punk, hip-hop, magazines, record companies. He told a hilarious story about sitting on U2’s DC-10 ($10,000 a day) while a waitress lit cigarettes for Bono as he talked about meeting Fidel Castro; they waited for hours to take off because Kevin Costner’s private plane had runway priority, and the “Postman” was late!

But he wouldn’t let me ask formal questions or turn on the tape recorder, and over the next three weeks, we traded phone message after message about setting up our “real interview,” with de la Roche always calling faithfully to explain why we couldn’t talk just yet—he was too busy to “focus”; he was buggin’ about the information tables at upcoming concert dates. From San Francisco: “Dude, I got a gang of shit going on here! We’ll talk in Utah. I promise! I don’t know anyone in Utah.” From Salt Lake City: “Bro, I’m really stressed, and I know I’m putting you through hoops, but what do you think about Chicago?” Having been blown off by the worst of them. I genuinely found this endearing. But it still exposed Rage as a frantic work in progress.

***

Tom Morello, boyishly dressed in a Chicago Cubs baseball cap and GOOD GRIEF, CHARLIE BROWN T-shirt, turns up, on time, no crisis, for our interview at an upscale sushi restaurant in West Hollywood, and that’s no minor accomplishment. Post-Woodstock ’99, the world’s potentially biggest rock band is without management (longtime comrade Brigitte Wright was dismissed bitterly, and the band declines further comment). In the month after Mexico, we will cancel/reschedule arrangements at least 16 times over nine cities.

Rage’s members are of remarkably like minds on most political/musical matters, but they wander their own paths and see the world from specifically skewed angles. On the subject of no manager:

“At first, it was empowering, then when I realized we’d never have another free second. I was like. ‘Oh shit, we need help, now!” [de la Rocha]

“It’s kinda crazy, man. The four of us are forced to talk to each other, instead of withdrawing and going through other people, which is how success screwed us up.” [Wilk]

“I’m not trying to bum you out, but dude, anything that doesn’t have to do with playing, I dodge it as long as I fucking can.” [Commerford]

“There’s no difference; we have people who can take up the slack. The whole boss/guru thing is overrated.” [Morello]

The band’s oldest member at 35. Morello plays the role of bottom-line anti-authority figure, defusing controversy two ways—with a heated, concise rebuttal or a practiced little chuckle that says, “Come on now, you can’t be serious! Asked about charitable contributions, he’s got numbers: approximately $80,000 from a New Jersey concert for Mumia Abu-Jamal’s defense (an essential factor in his December stay of execution): $400,000 from U2’s Popmart tour, split among four activist groups: $1.50 to $2 donation to local charities per ticket on a recent tour, etc.

Morello was virtually destined to battle or mediate. His dad, whom he didn’t meet until he was 30, was a Mau Mau warrior in Kenya’s purging of British rule and was among the country’s first representatives to the United Nations. When his parents divorced a year after his birth, Tom and mother Mary, a white schoolteacher, moved halfway across the country—from New York City’s Harlem to Libertyville, a suburb of Chicago—and into another cosmos. Morello may have been an unwelcome alien among the malls and mullets of Libertyville (the noose he found in the garage one day was a hint), but he became part of the tribe, banging his Afro to Iron Maiden and Kiss.

“I wasn’t even the cool kid at the arena show!” he laughs. He bristles when people dis Rage for appealing to the average dude (“I take it as a personal insult on where I grew up”). But after his mom, who founded the PMRC antidote Parents for Rock and Rap, bought him a copy of The Black Panthers Speak, he became isolated again as a political obsessive, following IRA hunger-striker Bobby Sands day after day. “He was about a year older than me, and my friends were, like, trying to lose weight to get on the wrestling team, and he was dying, because he believed in something!”

Though a Harvard honors grad (in social studies), Morello fantasized about mixing arena fleshpots with Marxist, well, who knows? He saved $1,000 by teaching guitar lessons at his mom’s house and headed to L.A. “I was in that lineup of idiots who bought the dream that Circus magazine sold me,” he says. A black, leftie, Ivy League rock geek, Morello adopted a “practical” plan of action. “I put an ad in the Music Connection for socialist singer who likes a combination of Black Sabbath. Run-D.M.C., and the Clash,’ and these guys with long blond hair and spandex would show up. I’d actually ask them to fill out this questionnaire, like, ‘What gear do you own? What context do you have in the music industry?’ I’d ditched my ‘fro, so I’m sitting there with this Lionel Richie, ‘Dancing on the Ceiling’-lookin’ hairdo! They must’ve been, like, ‘Who the fuck is this Negro?” He ended up doing disillusioning time for Democratic senator Alan Cranston until finding his niche with funk-rockers Lock-Up, then Rage.

Morello is the sort who would copyedit website addresses on album liner notes (not an insignificant detail in Rage’s world). He’s so used to offering up a slick position paper every two seconds that he often sounds like a deep-voiced radio DJ doing station IDs. But compare the arguments of Noam Chomsky acolyte Morello with the often scattershot, off-the-dome press communiques of Chuck D or Joe Strummer; he does his homework and forces other band members to stay on point. Like de la Rocha with Chiapas, he’s zeroing in harder on the unglamorous specifics of activism, primarily with the garment-workers union UNITE! and what he sees as the race-based adjudication of Abu-Jamal. Indefensible words once spewed in glib defense of Peruvian/Maoist terror squad Sendero Luminoso (a.k.a. the Shining Path) are now kept under his COMMIE cap.

With World Trade Organization protests blowing up in Seattle and concern growing that every “hip” garment we buy is the result of shady, outsourced labor, the anti-sweatshop movement may hit closest to Rage’s core fans (the video for “Guerrilla Radio” viciously spoofs a Gap ad). It also flows through de la Rocha’s U.S./Mexico pipeline; in 1997, the Apparel Manufacturers Association reported that Mexico shipped more than $3.5 billion of clothing to the US., manufactured for an average wage of $1.08 an hour.

Alex Zwerdling, 21, a senior at Vermont’s Middlebury College and a United Students Against Sweatshops activist, got a call last year from a band representative, asking if he wanted to be their (rather unfortunately named) Freedom Fighter of the Month for November ’09 and prop his cause on the heavily traveled Rage website.

“I was a little embarrassed, to be honest,” says Zwerdling. “And at risk of pissing off the band, there was the issue of them being anti-corporation and anti-whatever else, but they’re on Sony, a massive multinational corporation. I did get some shit from activist friends on campus. And maybe [Rage] aren’t as pure as they’d like to be, or as they’d like to look, but they’re trying to give us a voice, and we’re trying to give the workers a voice. Now they seem to be bringing the message in a more informed way.”

Rage have entered the political fray most prominently in the U.S. with their support of Abu-Jamal, the former NPR essayist and Black Panther sentenced to death in a much-disputed 1982 conviction. It’s interesting that when Rage finally threw down hard with an African-American-related cause, they received their harshest criticism. The Fraternal Order of Police, a right-wing group based in Nashville, called for NBC to cancel Rage’s appearance on Late Night With Conan O’Brien and placed Rage on a “hit list” of celebrities it opposes (from Michael Stipe to Bishop Desmond Tutu).

In addition, the New Jersey Legislature introduced a bill extracting $80,000 from the Sports and Exposition Authority’s profits to “discourage” events like Rage’s 1999 Abu-Jamal benefit (the money will support a charity for families of slain cops). Says FOP National President Gilbert Gallegos: “This is a mediocre band, at best, whose real talent is marketing an anti-everything image … We should not have to sit idly by and allow a murderer to be celebrated.”

The FOP doesn’t fuck around (it’s been feted in the White House), and if Rage want to duke it out in the U.S. politically this is who they’re up against. Few hip-hop stars have touched Abu-Jamal’s case (Black Star is an exception), and the rap industry’s apolitical, pay-me-now moment keeps Rage at arm’s length as well. DJ Premier of Gang Starr, which opened Rage’s US. tour in December, performed the miracle of mixing Limp Bizkit onto hip-hop radio and would love to do the same for Rage. “I told Zack to shoot me a few reels (“Mic Check,” “Calm Like a Bomb”), and let’s see what happens.” But he also cautions, “The difference between Fred (Durst) and Zack is that Zack is trying to penetrate the whole soul. Fred’s about having fun, and that’s all good, but Zack’s speaking the real, and that takes longer to sink in.”

The U.S. is a mass of tenuously segregated demographics, and Rage’s effort to chant down those divisions puts them alone in rock. The Mexico City show was exciting because art, commerce, media, and politics—plus people from north and south of the border—got in the pit together. The show was intended as a benefit for the Zapatista rebel communities, but in a letter printed by a daily paper the week of the concert. Marcos asked Rage to donate the money to flood victims instead, both a humanitarian gesture and a crafty political move. Further tweaking the ruling party. de la Rocha and a film crew (including old punk buddy Cubby Haworth) produced several short Zapatista pieces that MTV aired as a condition of broadcasting the concert. Later, de la Rocha et al. met with students who’d occupied the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) since April ’99. challenging the school’s privatization and proposed tuition hike. Their filmed spots tied the sit-in to bloody 1968 student protests (and to the roots of the EZLN—Marcos, a.k.a. Rafael Vicente, was a philosophy student at UNAM in the late ’70s). The segments aired in the time slot of Total Request Live (usual home to Christina Aguilera’s belly button), along with the band’s live-in-studio performance.

It was a savvy media blitz. But in the U.S., such moments have been the exception—partly because Rage have only released three albums in eight years, partly because their marketing/publicity machine has sputtered aimlessly (street teams, anyone!), and partly because they’re micromanaging an operation that requires a small army to run. But if they had it all down cold, the band wouldn’t be as human, or as engaging. Sure, it may be impossible to pull off any kind of tough-minded, music-driven progressive politics, but at least the possibility still captivates somebody. And if that’s naive, then maybe we should all just shut up and wait around for President George W. Bush to hand us our walking papers.