This story originally appeared in SPIN’s March 2002 issue. In honor of Cohen’s posthumous album Thanks for the Dance, we’ve republished it below.

In 1994, Leonard Cohen disappeared from public life. Cohen happens to be one of the most underappreciated artists in rock’n’roll history. But in the early 1990s, with works like I’m Your Man and The Future, he was enjoying the most successful period of his long career. Younger artists (including Jeff Buckley, Nick Cave, Tori Amos, and R.E.M.) were covering his songs, and filmmakers such as Oliver Stone and Atom Egoyan were featuring his work in their movies. At age 59, Leonard Cohen seemed, somewhat improbably, at the top of his game.

Then he simply walked away. He left behind his legendary love affairs (affectionately and notoriously documented in many songs), his two-story home in Los Angeles, and, it seemed, his artistic career as well. He took up full-time residence at a retreat led by his longtime Zen master and elderly friend, Kyozan Joshu Sasaki, 6,500 feet up Mount Baldy, about an hour northeast of L.A. No one expected to hear anything more of him.

Then, just as quietly, Cohen left the center in 1999 and returned to his previous life. He’s released a new album, Ten New Songs, that is, in many ways, unlike anything he has recorded before. In contrast to the acerbic themes of I’m Your Man and The Future, Cohen’s new album is about the acceptance that comes after suffering and aging. It is not about a fearsome future; rather, it’s about a tolerant present. Like Cohen’s best work, it follows its own rhythms, shapes, and passions. And it hints at answers to two overriding questions: Why did he leave the world behind when the world finally seemed ready for him? And why has he returned with what might be called his bravest vision since his brilliant 1966 novel, Beautiful Losers?

The answer to both is: Something happened to Leonard Cohen while he was gone, something he’ll say only so much about. More on that later. Right now, there’s some catching up to do.

1998

It is a pleasant summer evening in Los Angeles, and I am meeting Cohen, currently touring in support of I’m Your Man, at his mid-Wilshire-area home. I have spoken with him on various occasions since 1979. I remember one telephone interview in which we were talking about romantic and sexual love—subjects that have always saturated Cohen’s work.

“People are lonely,” he commented then, “and their attempts at love, in whatever terms they’ve made those attempts, they’ve failed. And so people don’t want to get ripped off again; they get defensive and hard and cunning and suspicious. And of course they can never fall in love under those circumstances. By falling in love, I mean just to be able to surrender, for a moment, your particular point of view, the trance of your own subjectivity, and to accommodate someone else.” He paused. “The situation between men and women,” he declared, “is irredeemable.”

He paused again, then laughed. “Drunk,” he chortled. “Drunk again.”

This evening in 1988, though, drinks aren’t on the menu. Instead, Cohen is making chicken soup. Around the kitchen are a few small religious icons and portraits—some symbols of Cohen’s own religion, Judaism, a few bits of Hindu and Buddhist statuary, and a picture of Kateri Tekakwitha, the famed Iroquois Indian who looms over the narrative heart of Beautiful Losers.

Leonard Cohen was born in Montreal in 1934 into a family prominent in the Jewish community. But Cohen also found himself fascinated by Catholicism. “I didn’t experience any of the oppressive qualities of it,” he says, salting the soup. “I just saw the child, the mother, the sacrifice, the beauty of the ritual. And when I began to read the New Testament, I found a radical model that touched me very much: Love your enemy; ‘Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the Earth.'”

His sense of Jewish identity and interest in Christian iconography and redemption would figure prominently in Cohen’s work. “Like the families of many of my friends, my family gave me encouragement to be noble and good. When I was [at Montreal’s McGill University] and I started to write poetry and meet other writers, we had the sense that what we were doing was very important. We weren’t in London or New York—we didn’t have the weight of the literary establishment around to say what was and was not possible. It was completely open-ended. We had the sense of an historic occasion every time we gathered and had a glass of beer.”

Cohen also credits his summer camp experience—where the director was a socialist and a folksinger—as decisive. “He played good guitar,” says Cohen of the director, “and he introduced me to folksinging via unionism and left-wing thought. I found out about a whole leftist position, a resistance position. I’d never known there was anything to resist. I got a guitar, and after the camp season was finished, I started learning songs. I went down to the folk-song library at Harvard and listened. I didn’t see much difference between songs and poems, so I didn’t have to make any great leap between writing and singing.”

In 1956, Cohen self-published his first poetry collection, Let Us Compare Mythologies. It met with praise, and his next, The Spice Box of Earth, in 1961, fixed his position as Canada’s major new literary voice. By then, however, Cohen was living on the Greek island of Hydra with a fetching Norwegian woman named Marianne Ihlen and her son. The relationship began a pattern: Like many before and after him, Cohen would find himself drawn in by the assurances of domestic and sexual commitment but also confined by the realities of the same. Although he lived in what seemed like paradise, he remained restless.

Cohen kept writing, publishing the semiautobiographical The Favourite Game in 1963, and then, in 1966, Beautiful Losers. It is a formally daring and startlingly sexual work about a man’s search for transcendence amid romantic and historical betrayals, and many still cite it as a major event in postwar literature. It makes plain that if Cohen had desired, he could easily have reached for the sort of literary standing accorded authors such as Norman Mailer, Thomas Pynchon, and Henry Miller.

But Cohen’s ambitions were changing. “I’d got some very good reviews for Beautiful Losers,” he says, “but it only sold a few thousand books. It was like facing a hard truth. I really worked at this; I’d produced two novels, three books of poems, and I couldn’t pay my rent. This was serious, because I had people who depended on me.”

By the late 1960s, Cohen had drifted to New York City, where he realized that the ambitions of literature and the effects of popular music were not antithetical. “I bumped into Lou Reed at Max’s Kansas City,” he recalled, “and he said, ‘You’re the guy who wrote Beautiful Losers. Sit down.’ I was surprised that I had some credentials on the scene. Lou Reed, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs; all those guys knew what I’d written. I realized I hadn’t really missed the boat.”

His songwriting caught the right ears, and Columbia released Songs of Leonard Cohen in 1968. With classics like “Suzanne” (already popularized by Judy Collins) and “Sisters of Mercy,” it established Cohen as a spokesman for lost souls. But despite his new reputation, Cohen was increasingly forlorn, and his relationship with Ihlen was fading. “After my record came out, I theoretically had access to interesting people. But I still found myself walking the streets, trying to find someone to have a cup of coffee with. I began to develop this idea that some catastrophe was taking place. I couldn’t see why I couldn’t make contact.”

In 1969, Cohen met 24-year-old Suzanne Elrod, the woman with whom he would share his longest and most tempestuous relationship. (She was not the legendary “Suzanne” of his most famous song, though Cohen admits her name was part of the attraction.) The two formed what Cohen describes as a marriage, though it was never formalized. In the coming years, Cohen’s recordings (including Songs of Love and Hate and Death of a Ladies’ Man) were often-stark portrayals of the struggle for romantic faith amid sexual warfare and of hope in the face of cultural dissolution. Much of the work was about his stormy relationship with Elrod. (She “outwitted me at every turn,” he says.) They had two children together and separated in the mid-’70s.

Although Cohen’s music was growing more imaginative, his records sold modestly in the U.S. Legend has it that when Cohen first played 1984’s Various Positions for Columbia pooh-bah Walter Yetnikoff, Yetnikoff said, “Leonard, we know you’re great. We just don’t know if you’re any good.” Columbia declined to release the album Stateside.

By 1988, however, things are looking up. I’m Your Man, a grimly catchy record with moody electronic orchestration, is doing better than any other album Cohen has released in the U.S. and is even a bona fide hit in parts of Europe. When a newly enthusiastic Columbia grants Cohen an award for the album’s successful international sales, he replies, “Thank you. I have always been touched by the modesty of your interest in my work.”

After our talk over chicken soup, I travel to New York City to see Cohen perform a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall. It is a powerful show, and the song that seems to stir the audience most is “First We Take Manhattan”—a sinister tale of a terrorist’s revenge from I’m Your Man. Live, at the heart of a show full of songs about acquiescence and grief, it’s like a call to battle. (And 13 years later, when Jeff Buckley’s version of Cohen’s “Hallelujah” becomes VH1’s chosen requiem in the wake of the attacks on New York’s World Trade Center, “Manhattan” will sound like rueful prophecy.)

After the show, I visit Cohen in his room at the Mayfair hotel, just off Central Park. It is a hot, sticky afternoon, yet Cohen is dressed obliviously and impeccably in a dark, double-breasted pinstripe suit, with a crisp white shirt and a smart tie. Cohen insists that I take the most comfortable chair in the room, then calls room service to order me an ice-cold drink.

“These are extreme times,” he begins, after a few moments. As he talks, he stands up from his chair, unzips his slacks, removes them, and folds them carefully over the back of another chair. Cohen keeps his jacket and tie on as he sits back down. “I think we are now living amidst a plague of biblical proportions. I think our order, our manners, our political systems are breaking down. And I think that redemptive love may be breaking down as well.”

I’ve heard this sort of thing from him before. But is it depression or enlightened realism? He continues: “There is no point in trying to forestall the apocalypse. The bomb has already gone off. We are now living in the midst of its aftermath. The question is: How can we live with this knowledge with grace and kindness? That’s how I arrived at ‘First We Take Manhattan.’ We can no longer buy the version of reality that is presented to us. There’s hardly a song you hear-”

There is a knock at the door. “Excuse me,” says Cohen. He stands up and carefully pulls his pinstripe slacks back on, opens the door, and signs the bill for my cold soda. He closes the door, hands me the drink, takes his pants back off, sits down, and smiles warmly. There is nothing coy or ironic here—it’s a truly gentle and compassionate expression. I realize then that Leonard Cohen is demonstrating how one behaves with grace and etiquette, even though he’s consumed with the dreadful knowledge that we are all living on borrowed time.

On 1992’s The Future, Cohen would traverse emotional lines he had not crossed before. “Things are going to slide in all directions,” he sings on the title track. “The blizzard of the world / Has crossed the threshold / …Get ready for the future: It is murder.”

I have always liked songs and art that are both honest and merciless, but I have to admit that “The Future” scared the fuck out of me. I decide that first chance I get, I will catch up with Cohen again and see how he is holding up. But by then, he is gone—moved on to a place where questions about his art would seem to have no further usefulness.

2001

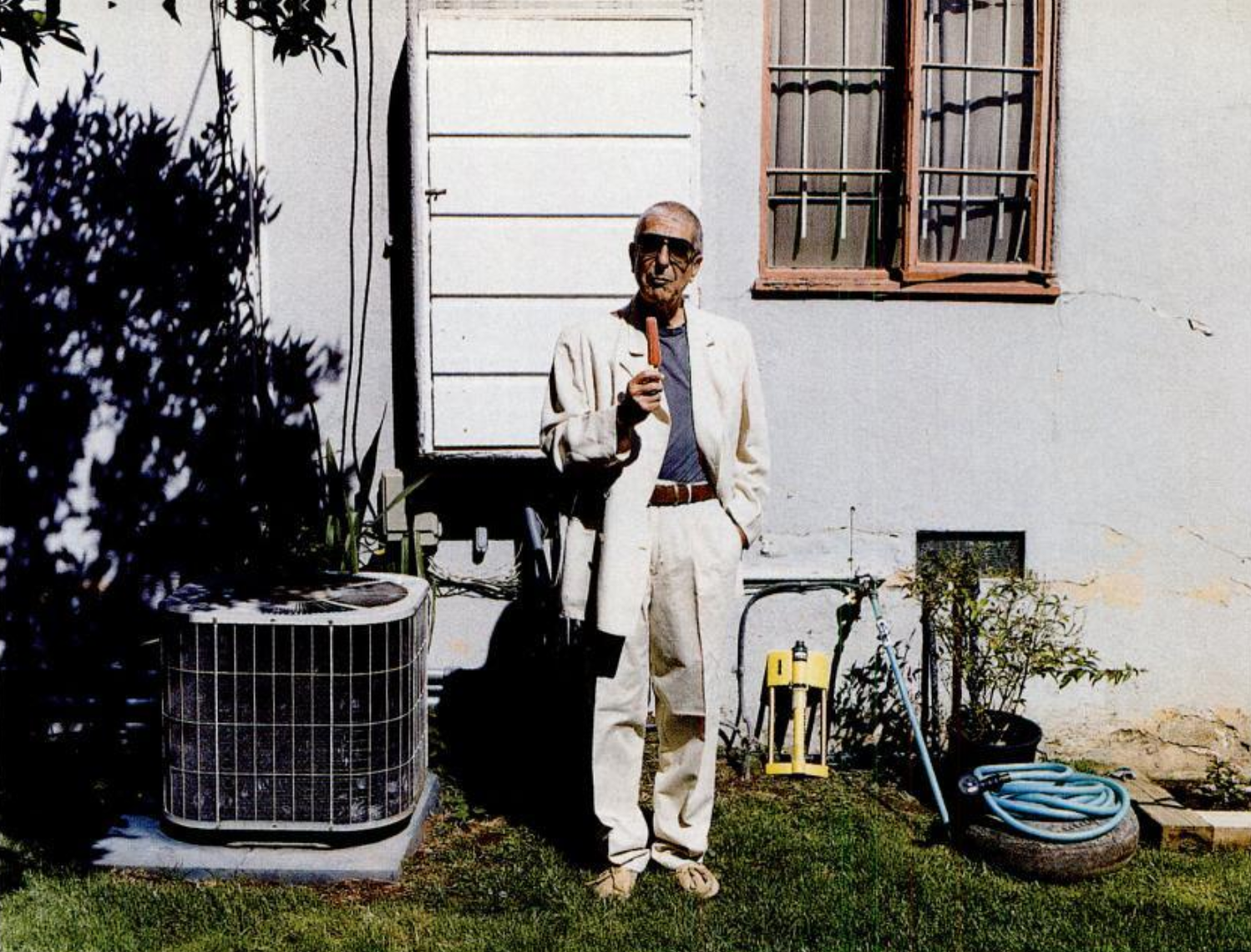

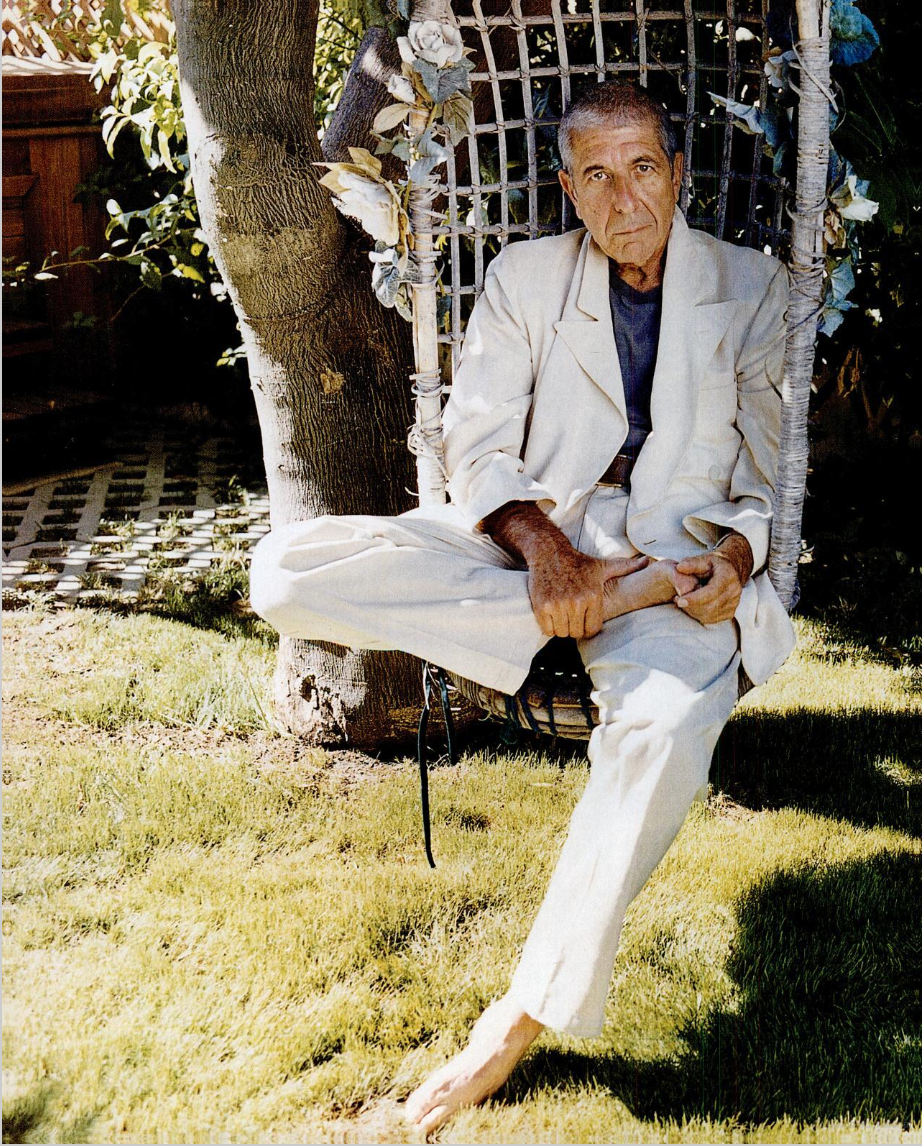

I am knocking on the same door to the same house in Los Angeles. The man who answers again wears a beautiful suit and again insists I take the most comfortable seat. Of course, Leonard Cohen has also changed a bit: He is 66 now, and he wears his pepper gray hair in a shaven crop.

Cohen left the Mount Baldy center in 1999, after a five-year residency. We are meeting now to discuss Ten New Songs. The record begins in reverence for things past and ends with a prayer: “For the millions in the prison / That wealth has set apart / For the Christ who has not risen / From the caverns of the heart… / May the lights in the Land of Plenty / Shine on the truth some day.” Conceptually, it seems miles apart from The Future‘s fearful fatalism. “The Future came out of suffer-ing,” Cohen says simply. “This came out of celebration.”

When he first returned from the Zen center, Cohen had no immediate plans for recording. Then, one night at the Beverly Center mall, he ran into Sharon Robinson, a good friend who had done backup vocals on some of Cohen’s earlier work (Cohen is godfather to her son, Michael). Before long, the two began swapping tunes. As it happened, Ten New Songs was written and performed almost entirely by Robinson and Cohen. “I think it’s a fine piece of work, and Sharon did most of it,” he says. “Occasionally I would make some adjustments. I’d say, ‘Sharon, does this tune have more than four notes? You know the limitations I have.'”

Cohen picks up a pack of Vantage cigarettes and lights one. He smokes them almost nonstop throughout our conversations. “I started smoking again about a year ago,” he says apologetically. “Got to quit again.”

I ask Cohen the obvious: Why did he withdraw from his career? He studies his cigarette. “The whole market application felt remote to me,” he says. “I was 58; I had the respect of my peers and another generation or two. But my daily predicament was such that there wasn’t much nourishment from that kind of retrospection. I went up to the monastery in 1993, after my last tour, with the feeling of, ‘If this works, I’ll stay.’ I didn’t put a limit on it, but I knew I was going to be there for a while.

“Also, I was there because I had the good fortune to study with Roshi [as Cohen refers to Sasaki, his Zen master]. He’s the real thing, man. He is a hell-raiser—there’s not an ounce of piety about him. This guy is smart enough to be rich, and yet he lives in a little shack up there in the snow. He’s a very exalted figure.”

The phone in the hallway rings. Cohen pauses to hear who might be calling, but the caller hangs up when the machine answers. Cohen smiles. “I offer a prayer of gratitude when no one leaves a message.”

Cohen begins to tell the story of the time he told Roshi that he wanted to leave the monastery and return to his life. “We are very close friends, Roshi and I. We were the two oldest guys up there, even though there were many years separating us. I had been cooking for him and looking after him for some time. So when I asked his permission to leave… disappointed is not the right word. He was sad—just like you would be if a close friend went away. He asked me why I wanted to leave. I said, ‘I don’t know why.’ He said, ‘How long?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, Roshi.’ He said, ‘Don’t know. Okay.'”

Cohen stubs out his cigarette and sits quietly. After a few moments, he offers to fix me lunch. (I learned long ago that it is impossible not to partake of food when you visit Leonard Cohen’s home.) Afterward, Cohen takes me to his recording studio, built above his garage. He lights up again and settles into a sofa.

“I can’t talk about what really happened to me up there, because it’s personal. I don’t want to see it all in print,” he says. “The truth is I went up there to address the relentless depression that I’d had all my life. I’d say that everything I’ve done—you know, wine, women, song, religion, meditation—was involved in a struggle to somehow penetrate this depression, which was the background of all my activities. But by imperceptible degrees, something happened at Mount Baldy, and my depression lifted. It hasn’t come back for two and a half years.

“Roshi said something nice to me one time,” he continues. “He said that the older you get, the lonelier you become, and the deeper the love you need. Which means that this hero that you’re trying to maintain as the central figure in the drama of your life—this hero is not enjoying the life of a hero. You’re exerting a tremendous maintenance to keep this heroic stance available to you, and the hero is suffering defeat after defeat. And they’re not heroic defeats; they’re ignoble defeats. Finally, one day you say, ‘Let him die—I can’t invest any more in this heroic position.’ From there, you just live your life as if it’s real—as if you have to make decisions even though you have absolutely no guarantee of any of the consequences of your decisions.”

It’s now late in the afternoon. Cohen trades one cigarette for another and pauses to admire the shadows cast by the lowering sun. “I’d like to continue working,” he says. “I hope I don’t fall over tomorrow. I have a whole new set of songs I’m working on, and I’ve returned to writing on guitar. Also, I’d like to publish my writings from Mount Baldy. It isn’t that in my life I had some inner vision that I’ve been trying to present—I just had the appetite to work. I felt that this was my work and that it was the only work I could do.”

Cohen puts on his suit jacket and walks me outside. “I’m in my mid-80s now,” he says. He looks up at the sun, which beats down hard. “I don’t pretend to have salvation or the answers or anything like that. I’m not saved.” He smiles. “But on the other hand, I’m not spent.”