This article originally appeared in the November 1988 issue of SPIN.

Hollywood is a town that knows the value of striking while the iron is hot, where filmmakers parlay overnight success into new film projects before lunch is finished. On the other hand, there is David Cronenberg. Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers is the latest film in an ongoing chain of “dream project”—like Oliver Stone‘s Platoon and Martin Scorsese‘s The Last Temptation of Christ—to have endured a decade of arrested development before receiving the benediction of production from a major studio. If writing is 50 years behind painting, as Brion Gysin claimed, cinema is lagging at least 10 years behind the imaginations of its own best practitioners.

Cronenberg’s career has, oddly enough, encountered more obstacles as his work has gained commercial acceptance. The popular success of The Dead Zone (1984) was followed by an unbelievable 13 drafts of Total Recall, an expansion of Philip K. Dick‘s story “We Can Remember It Wholesale.” After his favorite draft was vetoed by DEG studio chieftain Dino DeLaurentiis and producer Ron Shusett, Cronenberg bowed out of the project. Three years—shot.

Cronenberg’s next original screenplay, Six Legs, a science fiction satire about bugs and drugs, was agented around Hollywood in the sobering wake of Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign visit. The Studios put the First Lady’s slogans into practice.

HBO approached Cronenberg with an offer to develop an original series for cable TV, encouraging him to get as “weird” as he liked. The writer-director developed a cast of characters for a program he envisioned as “Miami Vice Meets Williams Burroughs,” and delivered a series of episode treatments with titles like “Inner Beauty” and “Sex With Monkeys.” And the rest, as they say in the business of weird-but-not-that-weird, is hysterectomy.

His next feature, The Fly (1986), became the most acclaimed horror film of the ’80s. Still contracted to DEG for another picture, Cronenberg began pre-production on Twins—more inspired by than based on the 1977 Bari Wood/Jack Geasland bestseller—a dream project on the back burner since 1981.

A 63,000 square-foot warehouse in Ontario, Canada, was secured to house the film’s sets, but as costly construction neared completion, unexpected news arrived. DEG’s roster of 1986 releases (Maximum Overdrive, King Kong Lives, and the like) had met with near-unanimous box office rejection, and Twins was named among the first casualties of a night-of-a-thousand-knives at DEG. (This was especially ironic as David Lynch‘s dark and uncompromising Blue Velvet—the DEG release which Twins most resembled—had been the company’s only recent hit.)

Meanwhile, Cronenberg learned that Universal was preparing a comedy with the same title. Reportedly, Universal felt that ads featuring the absurd proclamation “Arnold Schwarzenegger—Danny DeVito—Twins” would be worth millions at the box office. Cronenberg was convinced—for an undisclosed but persuasive sum—that the film needed the title more than his own.

Cronenberg’s film—now titled Dead Ringers—was ultimately financed by a Canadian development loan and a variety of theatrical home distribution deals. In other words, Dead Ringers—a cheap pun that hardly prepares you for the challenges and subtleties of the film itself—is Cronenberg’s first independent production in the eight years since his first hit, Scanners (1981).

Dead Ringers is the tragic story of identical twin brothers, Beverly and Elliott Mantel (both played by Jeremy Irons), who share a prominent OB/GYN practice in Toronto, Ontario. The brothers are brilliant in different ways; Elliott has a genius for public relations, while Beverly, the one with what Cronenberg calls the “most naked, highly developed nervous system,” is almost religiously obsessed with “inner beauty” of women. He develops new gynecological tools in his spare time.

Their fraternal harmony is threatened by the appearance in their office of Claire Niveau (Genevieve Bujold), a TV actress in her 40s unable to conceive and desperate for the child she may never have. The ever-helpful Elliott has a fling with Claire, but it’s the Mantle’s practice to share the bolder brother’s conquests, and Bev falls acutely in love. When Claire realizes she’s become the unwitting fulcrum of a ménage à trois, she abandons both men and Elly initiates a self-destructive vortex that ultimately threatens to consume his twin as well.

Cronenberg’s best films have been justly celebrated for their insistence on a preliminary hour of seemingly “straight” reality, as a kind of foreplay to the deep penetration of their fully revealed, climactic horrors. Dead Ringers—which is being described as a “psychological drama”—promises to take this stylistic signature a step closer to what is known, in literary circles, as “magical realism”—that is, naturalistic storytelling that unexpectedly alters texture to accommodate realistic intrusions of fantasy and the subconscious, as popularized in the novels of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, J.G. Ballard and Thomas Pynchon. As Cronenberg himself has said, “The art of The Fly was to make the fantasy absolutely real, whereas the challenge here was to make the realistic seem fantastic.”

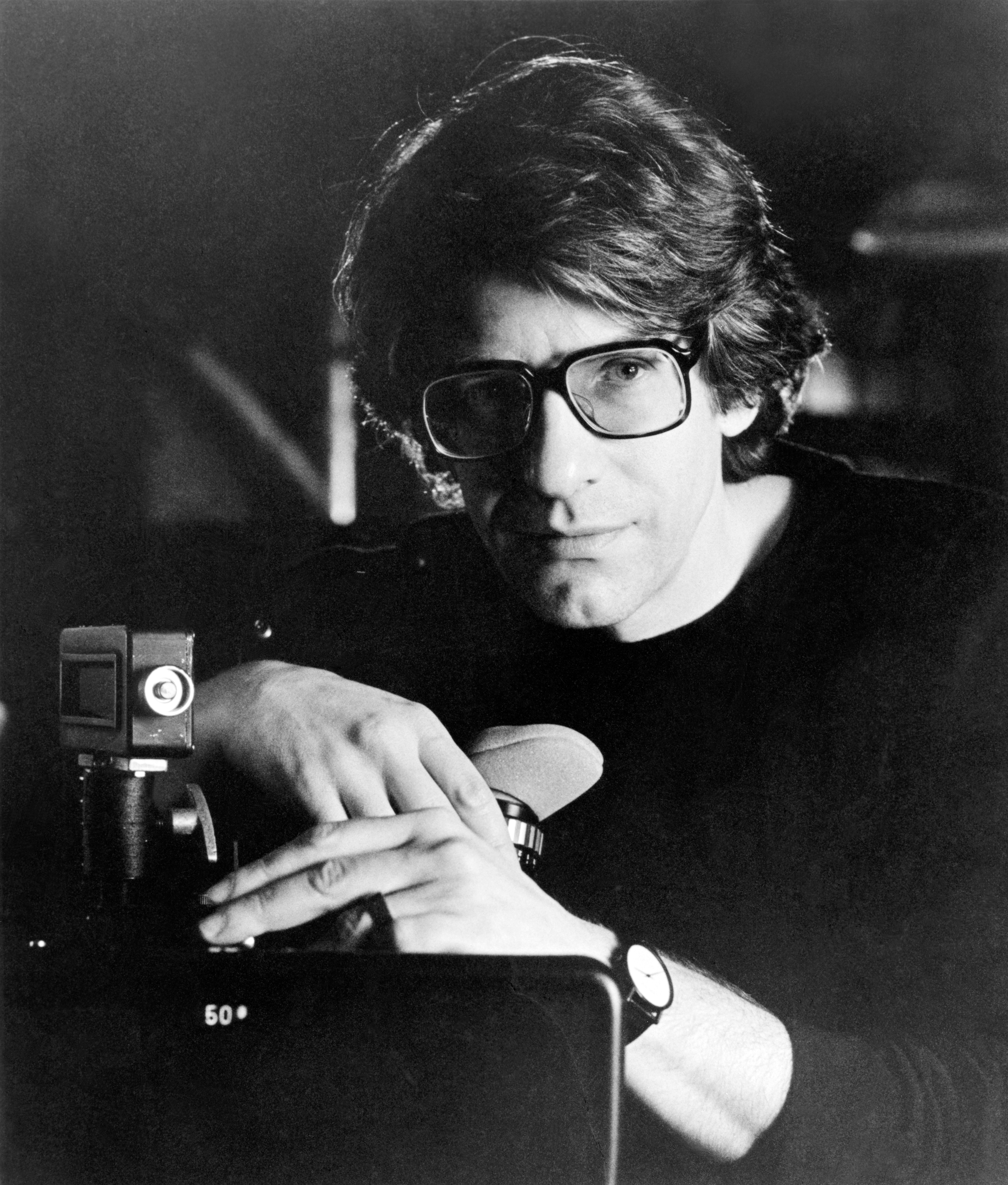

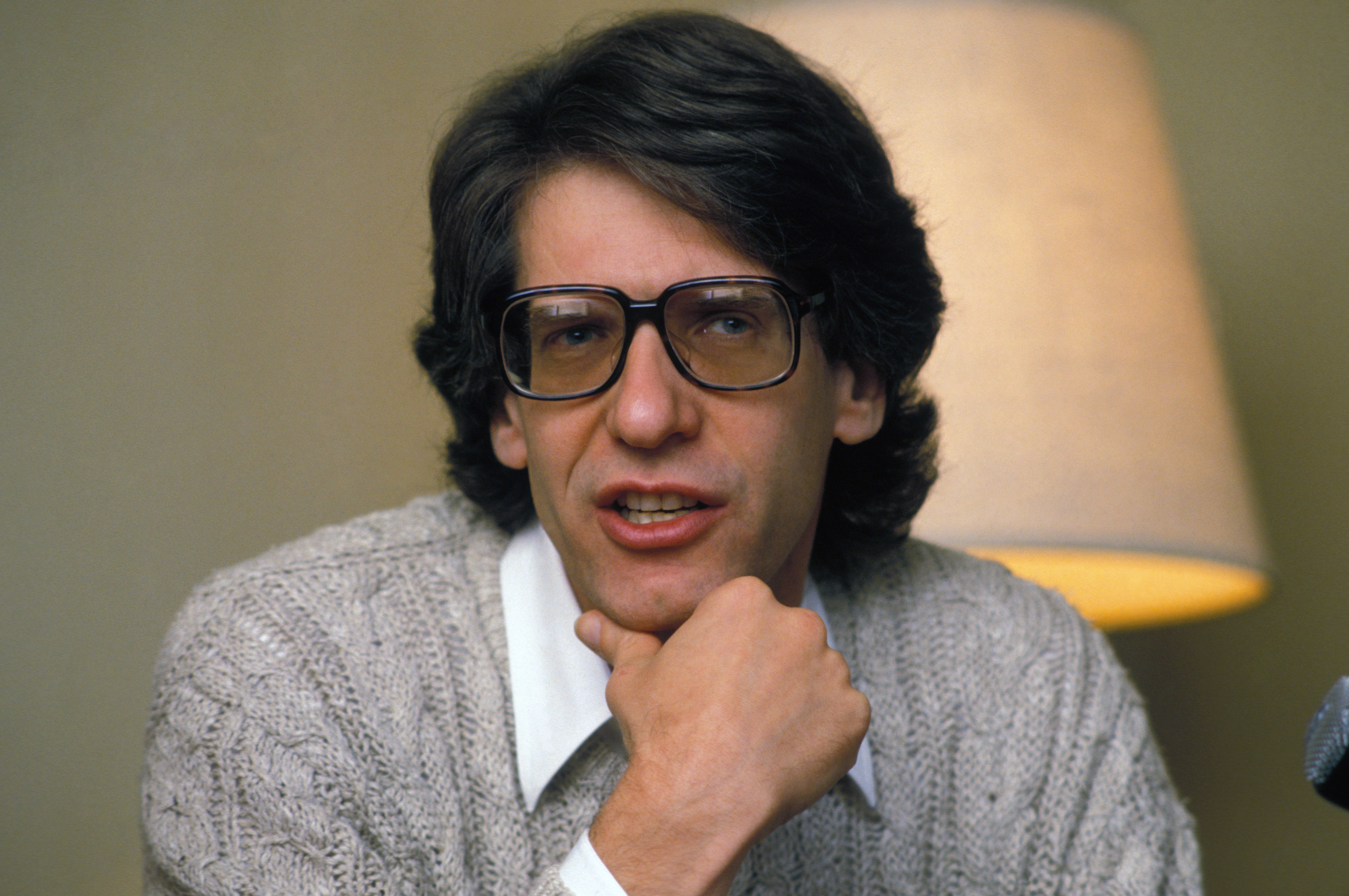

I met with Cronenberg in his two-room office in Toronto, a white-walled think-tank centered around a magnificent hard-disc word processor and a pair of Nautilus exercise machines employed to counteract a physically redundant lifestyle spent slouching over either Movieolas or PC keyboards. The offfice sports surprisingly little in the way of personal mementos—one shelf is adorned by a giant novelty store fly and another wall displays a small but striking German poster for Der Zonen Tod; a subtle confirmation of a tenant who prefers to look ahead from the perspective of a weightless present.

* * *

After Twins, a lot of titles were being kicked around. What were your criteria in selecting a new title?

Any title with the word “Brothers,” “Sisters,” “Split,” “Reflection,” “Double,” or “Mirror” was automatically disqualified.

I would suspect that there’s a certain element of your horror-film following that wouldn’t be able to follow you to this film’s new level.

Dead Ringers is not a kid’s movie. Dead Ringers is a very adult movie with concerns that are very adult, and I’m sure that a lot of kids would be bored with it, in the way that kids tend to be bored with adult movies. I haven’t tried it out yet on many kids but I’m going to. I’ll be very interested to see if teenagers can relate to it at all.

We’re in an odd position, marketing-wise, because I really wanted to separate this from horror because it would be a big mistake to attract only horror fans. I’ve been in this position before, but this case is even more extreme than The Dead Zone and Videodrome.

The Dead Zone, I recall, tested best as a straight suspense or dramatic film, but you had that title, a Halloween release date, and Stephen King’s name pasted all over it.

And here I’ve got Dead in the title again. Don’t think that coincidence has been lost on me for a moment.

I’m fascinated by this insane proliferation of twin scripts in recent years. It seems rather symptomatic of a very 1980s pass-the-buck attitude. You know, people saying, “Oh, it’s not my fault, it’s my evil twin’s doing.”

Well, it’s a nice thesis, and I certainly wouldn’t want to rain on your thesis.

Twins have always been fascinating, and there are so many aspects to the twin phenomenon, and its relationship to the mythology of the twin, and the metaphorical and psychological implications of twin-ness, and one element of that is exactly what you’re saying. It’s this schizophrenia in which one separates himself from what are basically his own responsibilities and actions, and thinks there is someone else, who is not quite himself, who is responsible. It’s like people who lead both private and professional lives, and there’s that schism—things that the private person does, the professional person would never do. That’s a little like Videodrome—in that case, it’s the celebrity persona that so many people have which isn’t really them.

I get the feeling this film will make some pretty pointed remarks about the subject of celebrity and glamor. Elliot is a very glamorous character, always making the public appearances at awards ceremonies, always the fashion plate, sexual adventurer and rake. You have him pontificate on the virtue of watching Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

But there’s the ugly inner life going on. And you show your glamorous actress heroine in a makeup room, having her eye blackened for her role as an abused housewife in a made-for-TV movie.

I don’t know how much you want to make of that. It’s just basic character definition. The difference between this movie and any other twins movie I’ve ever seen or heard of is that there is not an evil twin. They’re supposed to be real people, subtle, complex, difficult.

And that’s the challenge of the movie—for the actor and a lot of other people. There is no evil, psychotic twin, no purely opposite good twin. They are distinct people and they like and do different things, even when they live together. It becomes like defining a couple who spend a lot of time together, so this kind of character definition is essential. This is essentially a tragedy, so there is a rise and fall, and so the glamor and success of them as a unit musician be portrayed, shown, understood.

Your sister, Denise, who designed the wardrobe on this film, was telling me that she actually dressed the twins as children according to a photo of yourself from that period—all the way down to the glasses and jodhpurs that you wore. It’s been pointed out by a number of commentators on your work that you visually model your characters on yourself.

Do you think Jeremy Irons looks like me? [Laughs] I know, it’s ironic, isn’t it. I really wouldn’t have thought so, upfront, but he has so many different faces. He’s such an interesting actor to watch. He does look like me in a couple of the shots with his glasses on.

So would you go so far as to say you deliberately project your image into your films?

Not at all.

You played a gynecologist in The Fly.

Yeah, but with a mask on! And I was prepared to have myself dubbed, believe me, if I didn’t like my performance!

There are scenes in which Beverly is wallowing in the depths of his heroin addiction, or nodding out in the operating room. You also filmed a scene where Beverly’s receptionist comes into his office as he’s shooting up, and says, deadpan, “Doctor, I just can’t continue working here under these conditions.” It’s a quote from Williams Burroughs, and it was hilarious.

Sure, no question. I agree, it’s a funny line. [Pause, blinks.] What was the question? I was nodding out…

We did provide Jeremy with some things to read about the effects of barbiturate addiction. I gave him a copy of Jeff Coate’s Principles of Gynecology. I also gave him Leslie Fielder’s book Freaks, and The Two, a biography of Chang and Eng, the original Siamese twins. And we discussed the symptoms of taking barbiturates, but we also were determined to feel free of all that, to feel free to invent.

Because, in essence, none of that really matters. As usual, film tends to feel more accurate the more you wing it. Individuals react to drugs in very individual ways. We depended on each other to guide each other through all that, so it would work, so that it would be convincing, so that it would be horrible but not too horrible to watch.

Would you say those scenes will be humorous because they’re so horrible that the viewer will instinctively put up a wall of defensive laughter?

There’s an element of that, as in any black humor, but they’re also just plain funny. It’s no more than someone slipping on a banana peel—if it happens to you, it hurts, but to the person watching, it’s funny.

There are scenes in Dead Ringers, like the acceptance speech at the Feldman Awards where Beverly makes his first public appearance in a drunken state, that are funny and yet they’re also painful. And that’s the essence of black humor. There’s also an examination scene when a patent complains of something hurting, and Bev says, with more than an ounce of sarcasm, “This…hurts?” Well, in rushes, that’s excruciatingly funny but, as many people pointed out, in the context of the scene, it ain’t so funny. [Stage Whisper] Well, it’s still funny, but not as funny. For women, especially.

Women are going to have a harder time in store for them with this picture than men. Do you anticipate a feminist reaction?

If I were a feminist—which, in a non-militant way, I think I am—I would say that Dead Ringers is a very astute expose of certain things. The movie is partly about the whole attitude of certain men toward women. That’s what the whole opening scene with the two kids is about. You know, “If we can’t figure ’em out, we can dissect one.” Or, “If we can’t deal with them on a personal level, we can deal with them in a control situation.”

As gynecologists, they are in control of women’s bodies, they know more about women’s bodies. They are lying down with their feet in a stirrup and we walk in, in our official dress. Certainly this is material that is very hot for a feminist, but I wouldn’t know why if they would be upset by the movie. The movie is simply examining all of that, not saying that this is the way things should be. Not at all.

The doctors’ gowns had a look that was startling, intimidating, alien, and yet very familiar. The cuts of the hoods, the shoulder pieces, were somehow familiar.

Well, some of it was very papal. Very papal, like a college of cardinals. What I was suggesting…well, I was suggesting many things, it’s almost beyond verbalizing. In a way, the movie is a First Person, or Two First Persons, kind of movie. It’s right in their heads and that makes the operating scenes somewhat expressionistic, I suppose.

The look of the gowns reflect how they feel as they are operating, that it’s a priestly calling for Beverly, that it is not, for him, a job. It isn’t the same as Elliott feels, and we never see Elliott in those clothes. We only see Elliott talking about it. He’s like an airline pilot: “Here we are over the Grand Canyon, and we’re about to descend and cut out this woman’s uterus and replace it with stainless steel…” But for Beverly, it’s another world. It’s a religious experience, it’s a calling, it’s going underwater.

A number of your other films end in Heaven, or realms of alternative consciousness that are rather unheavenly. Does Dead Ringers end in Heaven?

Maybe.

What kind of reactions have you been getting from the preview audiences?

It’s interesting, but a lot of people noted in their cards that they really didn’t feel like writing about the movie after seeing it.

Dead silence seems to be a pretty common reaction.