This article originally appeared in the May 1992 issue of SPIN.

When you were young and your heart was an open book, you used to say, “Live and let live”—but not everyone concurred. There were members of a particular panda-eyed constituency who didn’t have it in them to stop and smell the roses.

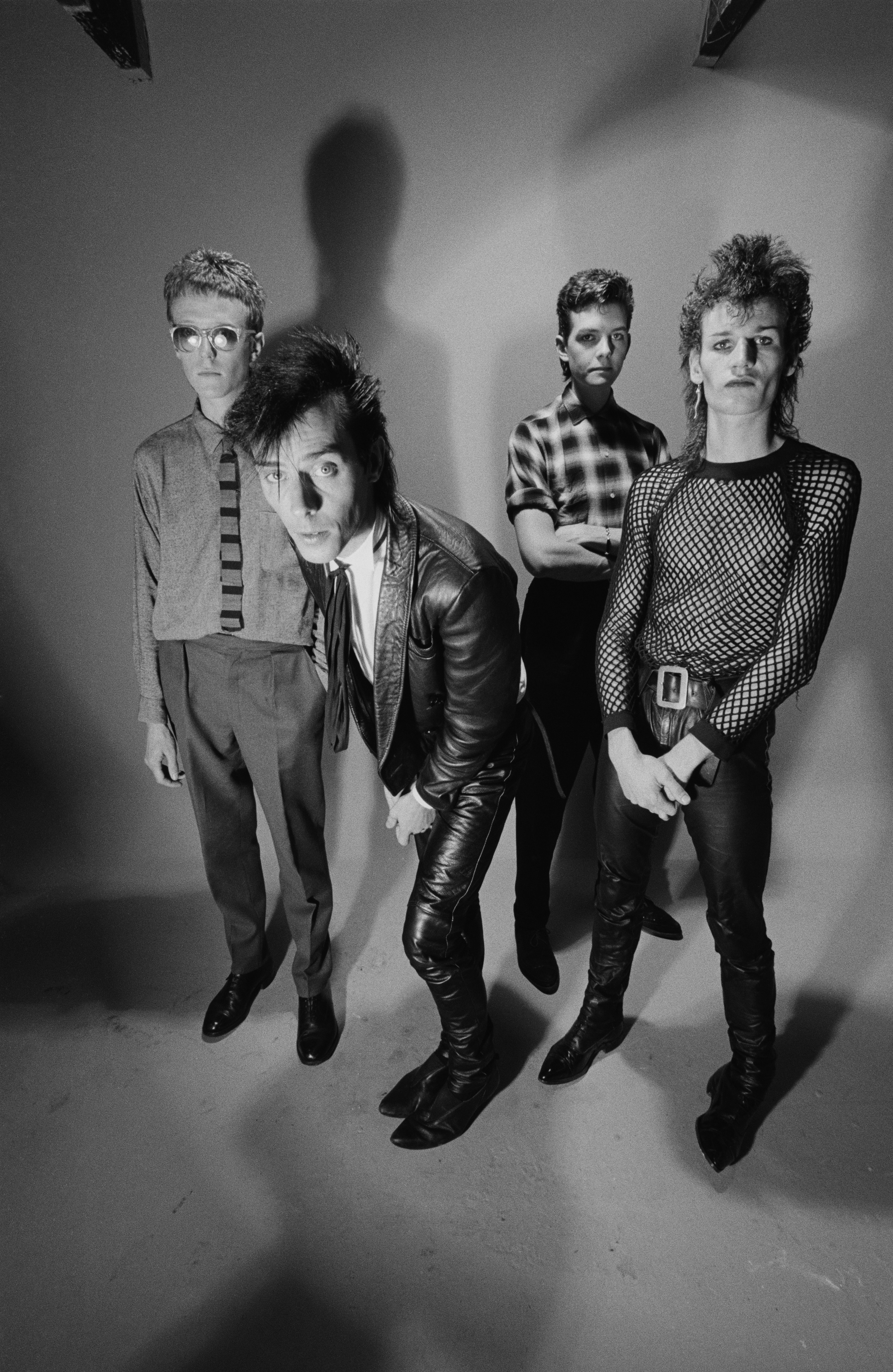

Goths, they called them—those little Vlads and Vampirellas, swaying numbly to the black mass of their choice, rendered catatonic by the pointlessness of it all. The most anthropologically unproved of all the postpunk convulsions, these chidden of the damned swelled in number but remained outside music-media scrutiny. Ignore their eerie presence though we may, every time an act nurtured by these necrophile manifests itself in the mainstream, a reminder is issued of their spending power.

Most goth outfits are mausoleum pieces in the U.K., but over on these shores longevity breeds legitimacy. Groups undead for a decade now find themselves major players: Witness the evermore-sprawling success of the Cure, the bloated breakthrough of Siouxsie and the Banshees, and the gradual ascendancy of one-time Bauhaus frontman Peter Murphy.

Journalists with sexier syntaxes than mine have gotten their laptops steamed up trying to do justice to Murphy’s boneless feline grace, his headlamp eyeballs, lethal cheekbones, and speaker-trembling baritone. Despite an increasingly warm-blooded body of work, the singer is defined by the single he’s moved furthest from. The brooding, ominous, ridiculous, and yet riveting “Bela Lugosi’s Dead,” a subculture standard, did Murphy both a big favor and massive disservice, tarring him forever with the bloodsucker brush. Less sphincter-shriveling in person, with the bearing of a down-at-heel balletomane, Murphy is well aware of the Dr. Doom persona synonymous with his name.

“That’s the way of the media,” he says with a shrug. “We tend to have an impression and that impression usually comes from the first moment of perception. I was perceived first and foremost in a band called Bauhaus, which had a song called ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead.’ People said that it was very demonic, very death-oriented, very mime-ic, very powerful visually.”

“There’s a certain saturnine quality about me as a person which makes me quite focused as a performer, quite tense. You find that hard to lose. Journalists tend to stick to that, because it’s good copy—it’s a biographical blueprint of a person. I understand it, but it can be frustrating. It’s not all doom and gloom just because you use the word death in a song. Depending on your perspective on that subject and the way it’s written about, it can be a very positive and light thing.”

While the United States slept, Murphy’s last offering, Deep, racked up sales of over 300,000. It would seem likely that the new album, Holy Smoke, his most cohesive and durable effort to date, will consolidate his U.S. standing. Nevertheless, he retains a sense of dislocation and—here it comes—alienation in his general outlook. Has this always been a part of his character makeup?

“Definitely,” Murphy muses. “When I was a child, I felt very dislocated from what was expected and what I was seeing around me as being the conventional way to live. It’s coming to the point now where that’s an unacceptable way to be. But back then, I didn’t realize that was the case until I got a point of reference. That’s when you get older, into your early teens. You start to see what might be called a more sensitive nature, which might be termed artistic, the source of wanting to create something. And you disappear into that.

“I always wanted to be able to speak and express myself in a way that wasn’t full of fear and inhibition,” he continues. “Being quite sheltered, coming from a working-class family, the main aim was a job for the rest of our lives. At the same time, there was that nonencouragement from the school system to be anything other than a laborer. A careers officer met you for half an hour, after five years of totally misfocused training of a young human being, teaching you useless information with no obvious applicable end and no sense of what university was. Going into life with that sort of backup can be, for anyone, quite a disorienting and frightening experience.”

“I basically stumbled around for five years. I loved singing, I knew that. All my friends had gone to art college, I had no notion of that. I came, as I said, from a working-class family who just wanted me to do what would make me happy—but what was happy? They couldn’t apply that to me. I had to find out for myself. I worked for five years, and at the end of that period I really started to get a crystallized feeling of actually wanting to perform. The moment I started working with Danny [Ash, now of Love and Rockets], it was like, ‘Oh God, at last, there is a way; I have got an ability.’ It was very intense, a real outpouring.” Did a similar psychological state motivate him to leave Bauhaus?

“I didn’t want to get out of the group and go solo. It was more like there was too much talent in the group and it had to fracture. Danny wanted to do his own thing. David [J, also of Love and Rockets] was always writing. My whole experience in Bauhaus was of a great focus—it fulfilled every possible need in terms of being creative. I wasn’t a musician, and this wasn’t just a band. This was my life. There was a twilight period after the band left, but by then I knew I was talented, I knew I could express myself. I could see there was a fame that I could build on.”

At this point we are getting along so swimmingly that it seems duplicitous not to admit that I had spent the previous, fun weekend prior to our meeting taking a crash course in his music.

“It’s frustrating that I know you’re just doing this for a job,” Murphy hisses, fangs bared. “There’s no soul there. I now feel that there’s no point in talking about it. I mean, why talk about something that the person hasn’t really listened to?”

I extricate myself, veins intact, by telling him I’m hearing his music the way most non-diehards will: fresh and without preconceptions. This mollifies him to the degree that he tells me the man who painted his house whistles along to his tunes without knowing what they are. Our exchange leaves me to wonder whether Murphy may not be a little over-sensitive, a little lacking in levity, a little—

“Po-faced?” he snarled. “Do you think I’m humorless?”

Well…

“I won’t take it personally.”

Well…

“You’ve been asking me quite serious questions, and I’ve been trying to answer them seriously. We don’t have a relationship where we’re able to laugh together.”

Maybe one day, Pete.

“Sitting here, I’m trying to strike a balance between answering you in a way that’s genuine and working it out as I go along. It’s weird when you’re focused on as an individual—but, yes, there is humor in my life.”