This article originally appeared in the July 1988 issue of SPIN.

Think of Disneyland on acid. No, make it a fistful of Dexatrim and a six-pack of Jolt Cola, with the spandex detector cranked up to ten. Think of marginally ham-fisted power chords, spiked with Maybelline and party-till-you-drop cartoon bravado.

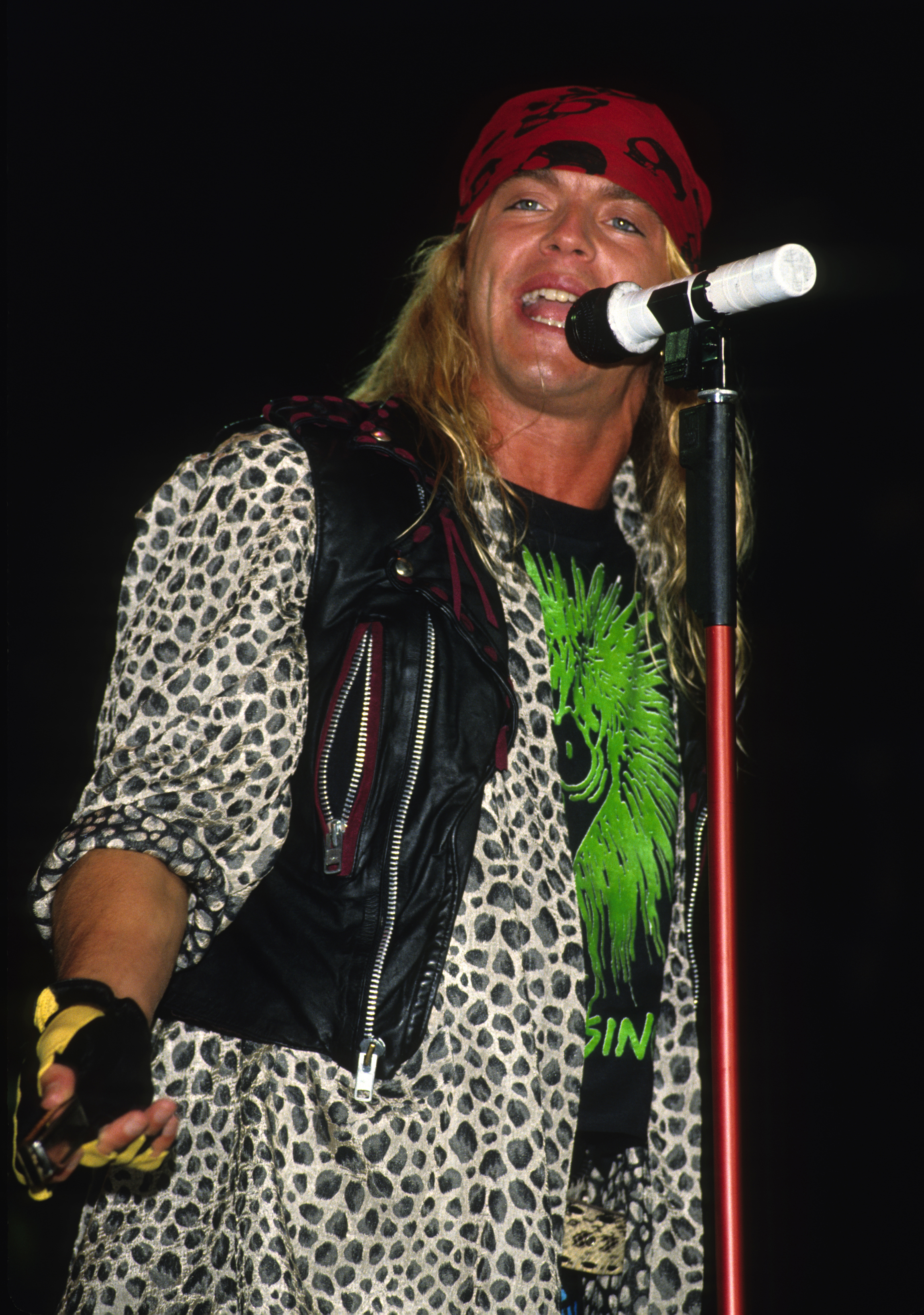

That’s Poison‘s schtick. Live and in blaring color, direct from the Sunset Strip. Depending on your tolerance for things that go kerrang! in the night, their garage-based, nuevo-metal glam is either the greatest thing since the return of shag haircuts and lip gloss, or heavy rock’s joke of the year.

But profits talk. Poison’s ragged, mid-’86 debut, Look What the Cat Dragged In, was recorded in twelve days and has since sailed well past double platinum. And with their second outing (the Tom ‘Mötley Crüe‘ Werman-produced Open Up and Say…Ahh!) now headed in the same direction, the Technicolor four are posing with a vengeance, presumably all the way to the bank.

“In the readers’ poll of every rock magazine this year,” says frontman Bret Michaels, “we were voted Best New Band and Worst New Band. To get that kind of reaction, you’ve gotta be doing something right.”

Or at least tried and true. With Poison out on the road with David Lee Roth, Michaels is sitting in a hotel room in Cleveland. It’s a town he’s seen before, and he doesn’t deny that many of Poison’s visual and sonic angles have also been seen before. An androgynous smidgen of the New York Dolls, a comic book dab of Kiss, a bludgeoning dollop of Van Halen and Mötley Crüe and…

Dubbed “all-purpose, convertible rock ‘n’ roll” by guitarist C.C. DeVille, it’s pretty goofy stuff—as calculated as a bunch of schoolkids running a Kool-Aid stand on a hot summer’s day.

Michaels prefers to see Poison as an attempt to bring back “a happy-go-lucky attitude” since, in his view, “too many bands are starting to take their personal aggressions out on the fans. They’re mad at the world and try to get their fans to feel the same. Rock ‘n’ roll is fun. We kick ass, but with smiles on our faces. We don’t have to be negative to get a message across.”

Granted, Poison’s sole message seems to revolve around girls. Preferably bad ones. It was while hoping to meed some, back home in Hershey, Pennsylvania, that Michaels crossed paths with drummer Rickki Rockett.

Inspired by Aerosmith, Van Halen, and Kiss, the duo began working with bassist Bobby Hall and a guitarist now long-departed, loosening the asbestos in the Rockett family basement with the Scorpions–AC/DC–Zeppelin songbook and a scattering of originals that, Michaels recalls, “were so fast that a ballad sounded like Metallica.”

But renting out VFW halls and hustling local bar owners for gigs had its limits, and the major labels weren’t exactly trawling the Pennsylvanian backwaters in search of new talent. It came down to relocating to either New York or L.A., though, as Michaels says, “New York was too close. We knew that when things got shitty, we would have just gone home. So we said, let’s pack our stuff and take our original set to Los Angeles, where it’s not going to be familiar and comfortable, where we’ve got to play music in order to live.”

They didn’t know a soul in L.A. and, in the classic manner, briefly fell in with Sunset Strip Svengali Kim Fowley. But the band didn’t feel ready for Fowley’s brand of wheeling and dealing, and instead set up living quarters at an old warehouse, where they turned to rehearsing and scrounging up gigs on their own.

“the first year you’re out there, you pay the clubs to let you play,” says Michaels. “You rent a depressing room at Club 88, and if you can get twenty people at your show and impress them, they’ll bring their friends next time and there’ll be forty. We were a promotion machine. We got a Thursday night at the Troubadour, then a Friday, then a Friday and a Saturday….”

It was a three-year grind, with the band members working at fast food joints and telephone sales jobs, “selling pencils to people in Iowa. Some days, we’d be eating Wheaties. Some days, somebody would turn up with a steak. But it wasn’t like after we did a gigi at the Troubadour, I went home to my parents’ place in Beverly Hills. I wish we could have had it easer. But because we had to fight for it, it makes us appreciate it that much more.”

When guitarist C.C. DeVille came on board (his first name is allegedly Cecil, and he once played in a band called Lice), the current lineup was complete. But though Poison was often attracting three hundred customers a night, the industry shunned them—the consensus being that the band was, even on a good night, fairly diabolical.

In the end, however, they snared a deal with Enigma that was later picked up by Capitol, which released Look What the Cat Dragged In in the early summer of ’86. It went nowhere for months, its inaugural single, “Cry Tough,” not even making it to within spitting distance of the Hot 100.

But on the verge of finally nose-diving into the cut-out bins at #191, the album suddenly did a U-turn and jumped 22 places. Poison immediately hit the arena circuit as show-openers for Ratt, and by the time the second single, “Talk Dirty to Me,” moved onto the charts, the four were up to their ears acting out all twelve volumes of the Rock Star Handbook.

“Our first time out, it was that whole firecracker-up-your-ass thing,” Michaels admits. “You want to be able to go home and say ‘I fucked a million girls, drank till I was shit-faced, shot heroin…’ You want people to think that’s the way you live.”

But we’re talking about a world where major rock bands routinely have tours subsidized by beer companies, where chugging down what’s alleged to be 90 proof, onstage in front of 10,000 rabid kids, has become a staple of many a performer’s predictable outlaw schtick.

Michaels concedes that if he’d been doing this interview a year ago, “even I would have been bragging, ‘Listen, I drink this much, smoke this much pot, and snorted this much blow last night.’ But now I can say how I really feel. I don’t go onstage and bring out a bottle. I have a beer on the drum riser, but it’s not to show off.” He laughs. “You know damn well anyway that if somebody really drank half a bottle of Jack Daniels, he’d puke right there.”

Question is, does the average small-town kid know it?

“I think they’ve started to learn it’s iced tea. And most are a lot more intelligent than people give them credit for.”

Undoubtedly. But there’s that moronic fringe, for whom a semi-comatose puke in the parking lot is the coolest conceivable capper to a perfect night out. Among some of the rowdiest of L.A.’s musicians (Poison included), the realization that some fans really do have trouble separating fantasy from reality has been sinking in—bringing with it a burgeoning, if clumsy, sense of responsibility.

Michaels recently joined the ongoing campaign for Rockers Against Drugs after falling off his Harley-Davidson while drunk. “I tell people that with a band like ours, we pay a bus driver to drive us after the gig—who is not drunk. Or stoned. I tell them to have a great time, but that I want to see ’em next year. I don’t want ’em wrapped around a telephone pole.”

But even for the band, Life on the Road is now filled with perils that Led Zeppelin, at their most debauched, never had to worry about. As Michaels says, “On our bus, we have a vending machine for rubbers. Costs fifty cents. So if you’re going to bring a girl on who you don’t know, it’s a smart idea to use them. And if she doesn’t care? You might want to think about how she probably didn’t care with the guy before you, and the guy before him.”

Common sense hits the fast lane.

“Yeah.” Michael laughs grimly. “Though sometimes, in the heat of the moment, common sense doesn’t set in until you’re ready to fall asleep. Then it’s ‘Oh my God, what did I just do?’ It’s the self-denial thing. With me, I though I was never, ever going to wreck a motorcycle. I’d been riding since I was little and…boom! It was that quick. No one thinks it can happen to them.”

Michaels is diabetic, which put an additional cramp in his style when, onstage at Madison Square Garden last year, he went into insulin shock and woke up looking at an emergency room ceiling. “I ran into problems mixing the drinking, the drugs, and the diabetes,” he says, adding that he cleaned up his act during a post-tour hospital say, then spent several weeks at a summer camp for diabetics, older and wiser, relearning how to keep himself alive.

“Every rose has its thorn,” he says. “Not only am I fighting the critics and everything else, I’ve got a disease that’s deadly. When I was growing up, I remember hearing about diabetics who played football. How it didn’t stop them. Now I’m getting letters from people who are diabetic or crippled. People who, by knowing about my situation, feel stronger that they can do it too.”

But the fact remains that Poison are still roundly dismissed as comic relief—about as aesthetically deserving of fame and fortune as our average, high-decibel, suburban high school combo.

“Our first album was basically a glorified demo tape,” Michaels admits. “Our second has production. The musicianship’s better. On our third, we’ll have to make another step forward, though the idea isn’t to solve the world’s problems. We just want to entertain.”

Is it art?

Michaels makes no judgement. All he’ll concede is, “I’m not Rembrandt,” and there’s a sense that, even as host of the part, he’s wary of his band’s multi-platinum success.

“I have these bad dreams of walking onstage, and it’s just a barren, empty room,” he says. “Nothing but a big echo. ‘Hello! How you doin’ tonight…night…night…’ I wish we had the polish that a lot of bands who’ve been around for years have. Look at David Coverdale. David Lee Roth has years of experience over me. I mean, when we first came out, we did arenas. I don’t think we were ready for them, but I think we got educated pretty well.”

A small boat in the proverbial big ocean?

“Yeah. And we’ve done the best with what we have.”