This column originally appeared in the June 1985 issue of SPIN.

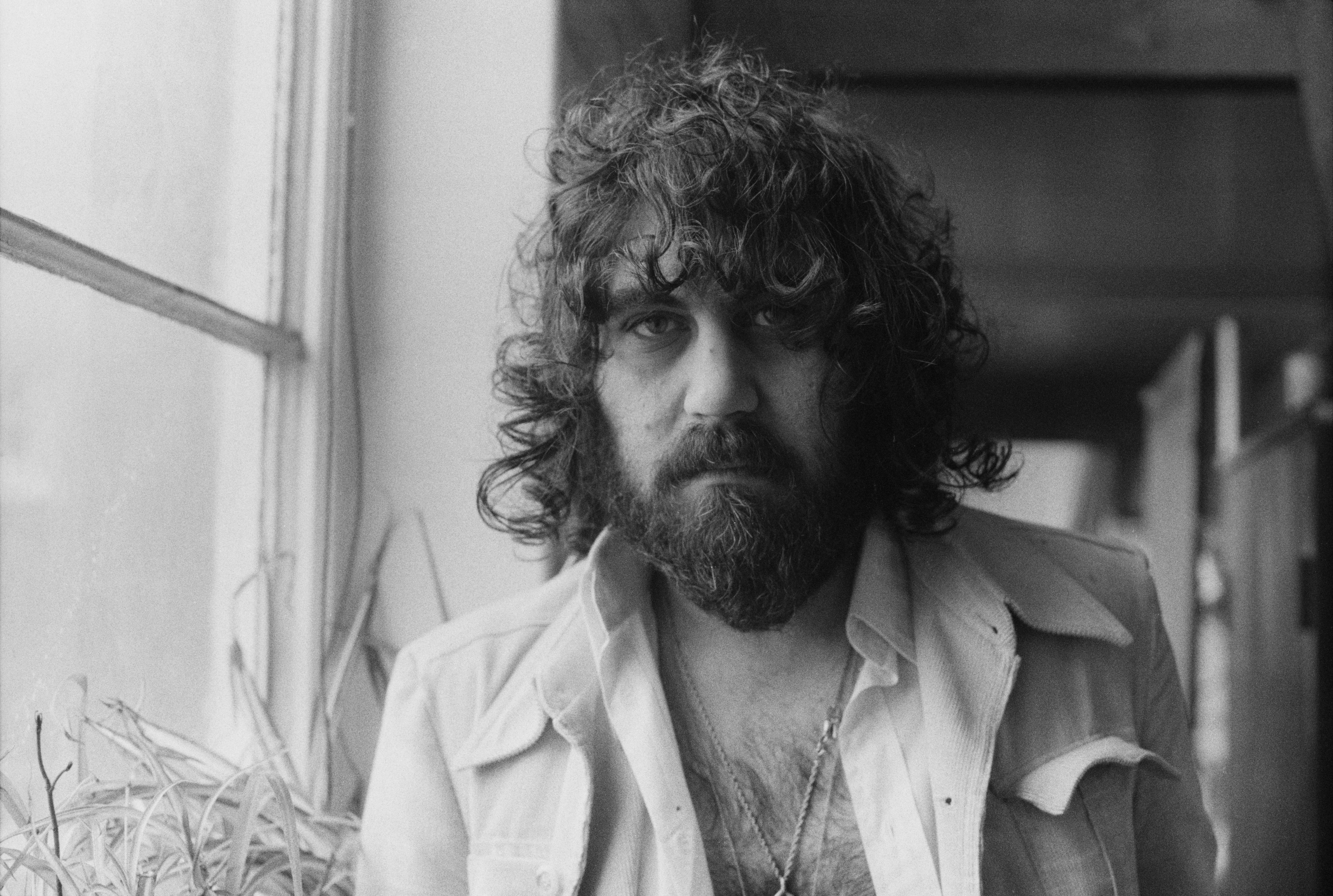

“I’ve always been anti-success,” says Vangelis. “Normally, after the success of Chariots of Fire, I would have immediately rushed to the States and started doing a big number with video programs, tours and concerts and such. I didn’t do any of that.” He didn’t even pick up his Academy Award for the Chariots film score. He has never toured in the United States, and until last year had never even been to this country. The Greek-born, London-based musician is one of the best known creators of electronic music today. Yet despite his commercial success—or perhaps because of it—his most remarkable achievement has been his ability to keep a low profile.

But Chariots was everywhere and, as a result, Vangelis has become at least a household half-name. “Vangelis Papathanassiou” probably wouldn’t be-come a household name no matter what he did. Knowing an obstacle when he smashed into one, Vangelis ditched his lengthy last name in the early ’70s.

However, if Chariots made his name more popular, Vangelis himself is still a shadowy figure. He hasn’t cultivated success. When the Oscar-winning Chariots of Fire soundtrack placed him in the limelight, Vangelis was shocked. “Nobody believed the film would be so successful,” he recalls. ‘When I wrote the score, I didn’t write it to be number one; I did it because I liked the people I was working with. It was a very humble, low-budget film.”

Vangelis has refused to fall into any of the superficial categories applied to music. By the time he won the Academy Award in 1981, he had been working in films and on discs for over a decade, building a sizable following among fans of both rock and electronic music (who are not necessarily the same people). The sheer diversity of styles he’s explored, and his refusal to stand in one musical place, make him the quintessential “new sounds” composer. His music inhabits a world that is not quite rock (though his earliest support came from rock fans), not really classical (despite the lush, almost symphonic quality of his synthesizers), and certainly not jazz (even if he does employ im-provisation).

Vangelis has recorded more than 20 albums, the latest of which is Mask. He has been recording since his days with the Greek rock band Aphrodite’s Child in the late ’60s. Leaving his troubled homeland in 1968, Vangelis moved to Paris, where Aphrodite’s Child made three albums. Unknown in America, their records sold over 20 million copies in Europe.

While in Paris, Vangelis met the talented French television director Frederic Rossif, for whom he composed a number of film scores. Finding the glare of pop success too uncomfortable, he began in 1970 to pursue a solo career. He moved to London and opened Nemo Studios, from which he has rarely emerged during the past decade. “Music for me is life,” he says. “I stay in my studio until ten or eleven at night and I record every day. Not for money or for albums—I just compose music.”

The wild diversity of the sounds that have come out of his studio is often startling. “When I’m successful in one field, I don’t stay with that, because I don’t want to become a prisoner of any label, any image.” The result is a series of records in a wide variety of moods: he can play an unusual but recognizably rock-based piece, or just take off for outer space—often on the same album. Usually it works, as in Albedo 0.39 and Heaven and Hell. Occasionally it doesn’t, as in Spiral.

In the 1970s came Vangelis’s fire-and-ice period: the celestial sounds of synthesizers, bells, and chimes contrasted sharply with the stampings of percussion and organ, and the rich waves of a chanting choir on Heaven and Hell. Recorded in 1975, H&H features the voice of Yes’ lead singer Jon Anderson. When Rick Wakeman split that group, Vangelis was recruited to take his place. But after several weeks of rehearsals, Vangelis was convinced that his musical direction and the group’s were a universe apart. Still, he and Anderson became friends, and recorded three albums together. “We went into the studio one day and started playing,” he says, “and a year after that we released the album. But we didn’t start out to record an album; it was just the pleasure of playing together.”

Since 1970, when Vangelis unveiled his lush, dreamy style with the film score L’Apocalypse des Animaux, his name has become synonymous with music of direct emotional appeal. But he wouldn’t be Vangelis if he limited himself to one mood: the Ignacio soundtrack is often chilling and sinister, with dirge-like choral effects and rumblings from a synthesizer or thundersheet; on Albedo 0.39, Vangelis creates a lighter mood—there are even a couple of pieces you can dance to (well, sort of).

Since Chariots, he has been cautious about the movies. “I don’t want to become a factory of film music,” he says. He turned down an offer to write music for 2010, but did score Blade Runner and a Japanese film, Antarctica.

It’s not difficult to see why Vangelis has become a popular musician in this field: Using layers of music, both electronic and acoustic, he is brilliant at setting a mood, whether that of running through the English countryside, braving the seamy underbelly of post-Apocalypse Los Angeles, or exploring the frozen wastes of Antarctica. As U2’s Bono Vox told SPIN last month, “He’s got a real emotion to his music.” Although he is a virtuoso synthesizer player, and can make one keyboard magically imitate a drum or a harpsichord, Vangelis’s albums never degenerate into showoff displays of hardware. Vangelis skillfully walks that fine line between possessing a distinctive style and becoming a self-parody, which accounts for his musical longevity, and his reclusive work habits enable him to avoid the pressure to repeat his successes. He avoids talk shows. What you’re now reading is one of his rare interviews. “When you compose music, that’s one thing,” he says. “But when you have to explain it, that’s much more difficult.” He doesn’t tour, though he enjoys playing for people (he punctuates his conversation with bits of music from one of the keyboards he always has nearby). “I don’t believe in playing in each town, and saying, ‘OK, this is my new album—can you buy my new album, please? I don’t like to be pushy, though I like to perform.” The problem, he says, is that “a concert or any public performance is a responsible gesture. It’s not for serving a promotional purpose or boosting a performer’s ego. Worst of all is this obligation to have a full house.”

In his own “anti-success” fashion, Vangelis has become a highly regarded musician. His studio recordings have been critically and commercially successful. His early 1985 release, Invisible Connections, is an atonal, experimental piece (released on the prestigious German “classical-music” label, Deutsche Grammophon). He wrote a ballet score in 1983 for a Greek production of Elektra. But he’s still wary of success. Two pirate albums appeared in 1980 and ’81 under his name. They were a transparent attempt to cash in on his sudden fame; the music was from a 1971 jam session—and a bad one, Vangelis admits. The tapes were taken, signatures forged, and two albums, Dragon and Hypothesis, made from them. Be warned: they’re awful. “Greed can destroy the world,” he says. “This person was greedy and just wanted to make some money. Although we won the case in court, the albums were already out, and I don’t agree with that music at all.”

Dodging the spotlight has allowed Vangelis to develop a unique style. But it has also led to some misconceptions. One is that he uses the latest in studio technology to the exclusion of everything else. In fact, he plays a number of acoustic instruments, and features a choir on his newest album, Mask. Other recordings make use of the fluegelhorn, acoustic piano and violin: “I don’t always play synthesizers,” Vangelis explains. “I play acoustic instruments with the same pleasure. I’m happy when I have unlimited choice; in order to do that, you need everything from simple acoustic sounds to electronic sounds.”

The other common misconception is that Vangelis is primarily a composer of film scores. But his last three albums have all been studio recordings; film music accounts for only a quarter of the albums he has produced.

Vangelis has released three albums in the past 12 months. Soil Festivities, released in late 1984, was his first domestic release since Chariots of Fire in 1981. He feels he still has a lot to say—in his music, at least. Now he’s using a more complex, almost symphonic language: Soil Festivities and Mask are arranged like symphonies or suites, divided into movements that present a wide array of moods. Mask is a dramatic, exciting work in six movements. In the fourth part, some complex percussion, strongly reminiscent of West African tribal drumming, gives the piece an exotic flavor; in the opening movement, Vangelis creates a flourish of sound on the keyboard, using a quick series of notes to propel the chorus and synthesizers into a crashing climax that would’ve done Richard Wagner proud.

“It’s very easy to go out of balance and to become a product,” he warns. “But music is so much more than entertainment, believe me. It’s an important human possession.”