This column originally appeared in the May 1985 issue of SPIN.

“My idea of hell is being locked in a room and forced to listen to this man’s music.”

“The most inane, boring, repetitious noise I’ve ever heard.”

“He belongs in a rubber room. I know that’s where I’d be if I had to listen to his stuff every day.”

Also Read

The 50 Best Albums of 1982

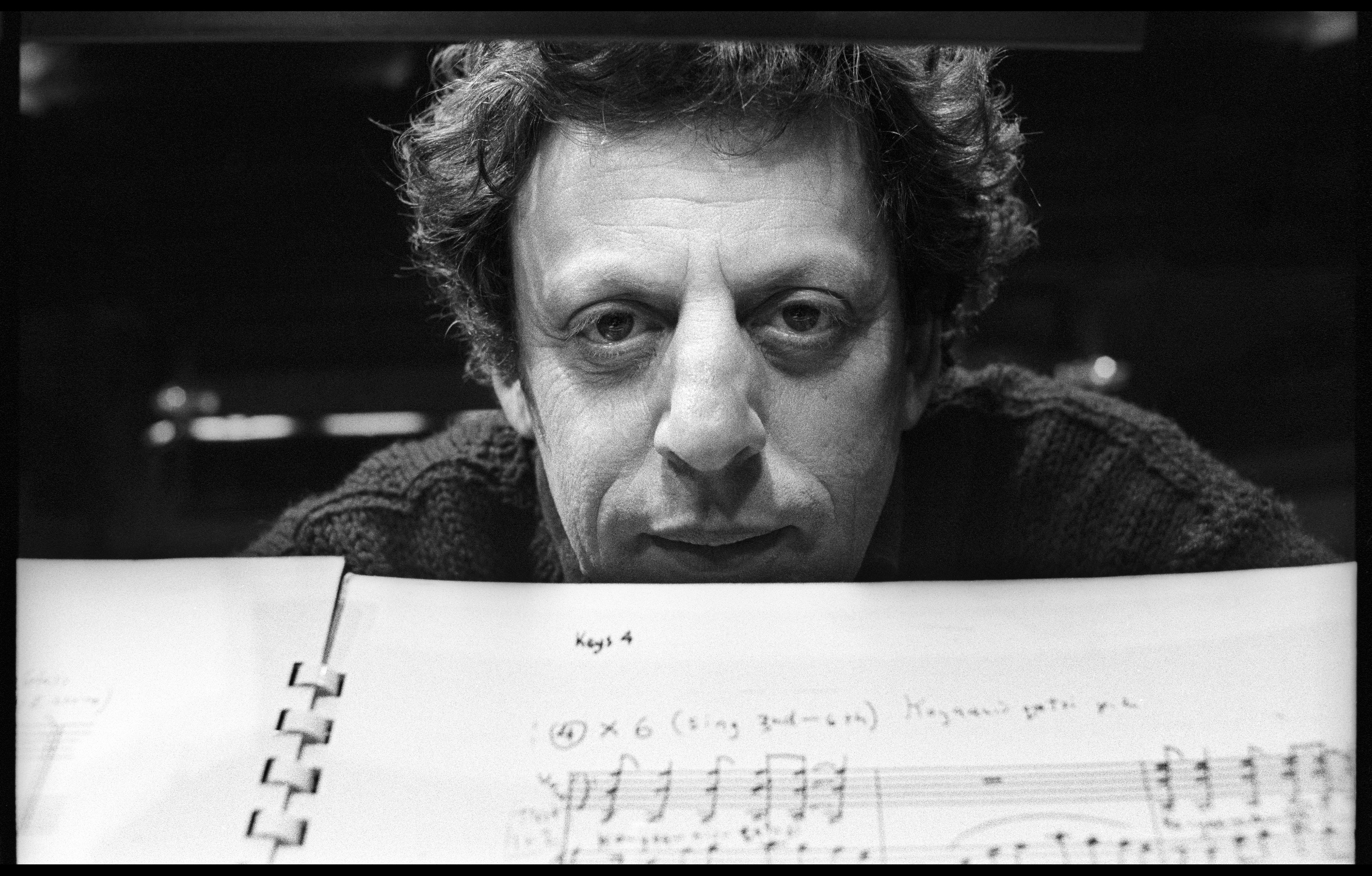

These comments from otherwise good-natured, reasonably well-adjusted radio listeners in New York were provoked by the music of one man. By now, Philip Glass has grown accustomed to such responses from listeners who are less than pleased with his pattern-oriented, back-to-the-basics style of music. “I certainly don’t expect everyone to like my music—of course I think they should,” Glass laughs.

Glass is an amiable, articulate musician whose success is the result of 20 years of hard work and perseverance. Evidence of that hard work surrounds us as we sit in the studio of his Lower East Side home. An upright piano occupies one wall; music paper is everywhere else. Glass is musing about the critics’ responses he’s had to face over the years. “Clearly they see themselves at the barricades of culture, beating back the barbarians. I happen to be a barbarian.”

Here Glass is interrupted—by a horrifying shriek. I sit riveted to the sofa in a state of near-terror. Glass walks out and returns in a few seconds.

“That’s my bird,” he explains.

A bird? “Yeah, I have a parrot.” And lest we forget it, the bird punctuates the rest of our conversation with occasional bursts of ear-numbing malevolence.

Glass, now 48, looks a good deal younger. In the past few years he has become the most prominent example of a musical trend usually called minimalism, although that term may be misleading. This style began in the 1960s as an attempt to create music out of simple ingredients—for example, repeating notes and chords in gradually shifting layers.

“I think people were hoping it would just go away,” Glass says, “and it just makes them angry that not only has it not gone away, but by God, it’s all over the place!”

Glass’s music is all over the place. Remember the opening ceremonies of the Olympics? Glass’s music was heard on millions of TV sets while Rafer Johnson took the torch and climbed those seemingly interminable stairs to the top of the L.A. Coliseum.

Although the Philip Glass Ensemble began performing in 1968, Glass didn’t really “arrive” until the early 1970s, when his group of electric keyboards, amplified voices, and wind instruments began attracting young listeners who were bored with the current rock music and put off by the complexities of modern classical music. Glass successfully combined the simplicity and rhythmic energy of rock with the classical composer’s concerns for form and structure.

Glass has done much in the past decade to blur even further the distinction between rock and classical music. A graduate of the Juilliard School, and presumably, therefore, a “classical musician,” Glass has nevertheless worked with David Byrne of Talking Heads, Paul Simon, Ray Manzarek of the Doors, and has produced albums by the Raybeats and Polyrock.

Glass enjoys working with rock musicians, despite the frequent differences in age. “When I worked with Polyrock, I was 20 years older than the guys in the band,” he recalls. “That was funny—they started off calling me ‘Mr. Glass.’ By the end of the recording session, that was forgotten. But Paul Simon and Ray Manzarek—we’re not that far apart in age. And age isn’t important; it’s how you think.”

Unfortunately, when a musician doesn’t fit into any of the usual categories, there’s a tendency to try to create a new one. The term “Minimalism” was offered as a convenient label for the music of Philip Glass and several other composers in the late ’60s. But there are a couple of problems with it. First, the chief examples of this alleged style—Glass, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, and John Adams—all dislike the term. The only major Minimalist who hasn’t publicly repudiated the label is the founder of the style, LaMonte Young, who remains a shadowy figure in contemporary music owing to the scarcity of his music, both on records and on stage. But no matter what Glass, Reich, and company have to say, the Minimalist label has stuck with them over the years, which brings us to a second, thornier problem. Simply put, “Minimalism” no longer describes what these musicians are doing. Maybe it was adequate for the highly repetitive early works of Riley, Reich, and Glass; but it certainly doesn’t do justice to the massive instrumental and choral forces employed in Glass’s recent theater pieces.

“Once I began working on large scale music/theater pieces in ’76, with Einstein on the Beach, it was pretty much the end of that period for me,” says Glass. “I don’t think the aesthetic of minimalism and the demands of music/theater go together very well. On the other hand, I don’t feel these new works invalidate the old works. We’re not toothpaste manufacturers, where a new brand will make the old one obsolete. A work from the early ’70s can still have appeal, and a point of view.”

“Success is perceived in a lot of different ways,” Glass explains. “In 1970 or ’71, when I did my first tour, I considered myself a success. I had my own ensemble, I was touring, I had an audience. I wasn’t making any money, but I thought I was a success. Then in ’76, there was a general public that thought I was a success. But until two years ago, when I could walk into a bank and borrow money to buy a house—that’s when the people who know about money thought I was successful. And that’s when I realized I was actually doing OK, when I could get a mortgage on a house. But I was 46 when that happened. So much for art and money.”

Glass held down a number of odd jobs until he was in his 40s before he was able to devote himself wholly to music. In fact, the 1976 production of the Philip Glass-Robert Wilson “opera” Einstein on the Beach at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House meant that there was one less taxi-cab cruising the streets. But though Einstein sold out both shows at the Met, it was still a financial disaster. Shortly after the work premiered, Glass was back in his cab, having turned down the Met’s offer of a third performance.

“We just couldn’t afford it,” he recalls. Glass and collaborator Robert Wilson were losing $10,000 a night on sold-out shows. “Opera houses are built to lose money. If we had been doing Carmen or La Boheme, we still would have lost money. The difference is that Bob and I didn’t have an opera company, so we took the loss ourselves. We’ll never make that mistake again.”

Since Einstein, however, Glass’s popularity has grown dramatically. The Philip Glass Ensemble is now a sure box office draw, whether in rock clubs or Carnegie Hall. Glass himself is one of the most sought-after figures in contemporary music, but he is somewhat bemused by the furor his works still create. “Einstein was a piece that made people take a stance one way or another; but certainly I never expected to be in the storm of controversy that Akhnaten produced, eight years after Einstein. It’s had extremely positive and extremely negative reviews; I haven’t read anything in between.”

Perhaps that’s why Glass seems so unaffected by all of the attention he’s received in the media and in musical circles. He’s lived in the same area of Manhattan since he first came to New York in the late ’60s, a slightly seedy part of the East Village that hasn’t yet been completely gentrified. “It’s happening,” Glass admits, “but it’s still a neighborhood.” Glass still inhabits the same world of simple chords and easily identifiable melodies and rhythms he did 20 years ago, although the scope and texture of his works has grown enormously. His works still use repetition, but where repetition seemed to be the whole point of some early pieces, in his recent works it’s just another tool. The simplicity and direct appeal of his music has affected a whole generation of younger musicians, from Kraftwerk to David Bowie.

Bowie says that several of his songs were influenced by Glass’s style. “Well, we’ve talked from time to time,” says Glass, “but we never really got into that. David’s music sounds very personal to me. Maybe there’s a little influence in something like Low, or perhaps the kind of slow pieces he did with Brian Eno.”

Certainly one key to Glass’s success has been his ability to attract at least a portion of the rock audience. By using rock technology, including synthesizers, Glass has been able to cultivate a sound that’s immediately identifiable … which is not to say that all his music sounds the same.

“There’s a tremendous pressure to repeat successes,” he says. “There’s also a kind of artistic inertia. So what I’ve done is create new problems: with Akhnaten I used a different orchestra, instead of the Ensemble. I just finished a score for Paul Schrader’s film Mishima; I wrote it all for strings and percussion, because I’d never done that before. And I figured one way to have a new solution is to change the problem.”

The music of composers like Philip Glass is becoming easier to find. Although his early records are now out of print, there area number of available recordings that might appeal to the adventurous ear:

Glassworks (CBS FS 37265). I’d hate to say this is a mellow recording, so let’s just call it his most lyrical.

Koyaanisqatsi (Antilles ASTA-1). A sound track (the title is a Hopi Indian word meaning “life out of balance”) featuring a huge ensemble. Very effective, very popular.

Dance I & 3 (Tomato 8029, scheduled for rerelease by CBS this year). Glass at his most accessible.