This article originally appeared in the October 2010 issue of SPIN. In honor of the 10th anniversary of Kid Cudi’s debut album Man on the Moon: the End of the Day, we’re republishing it here.

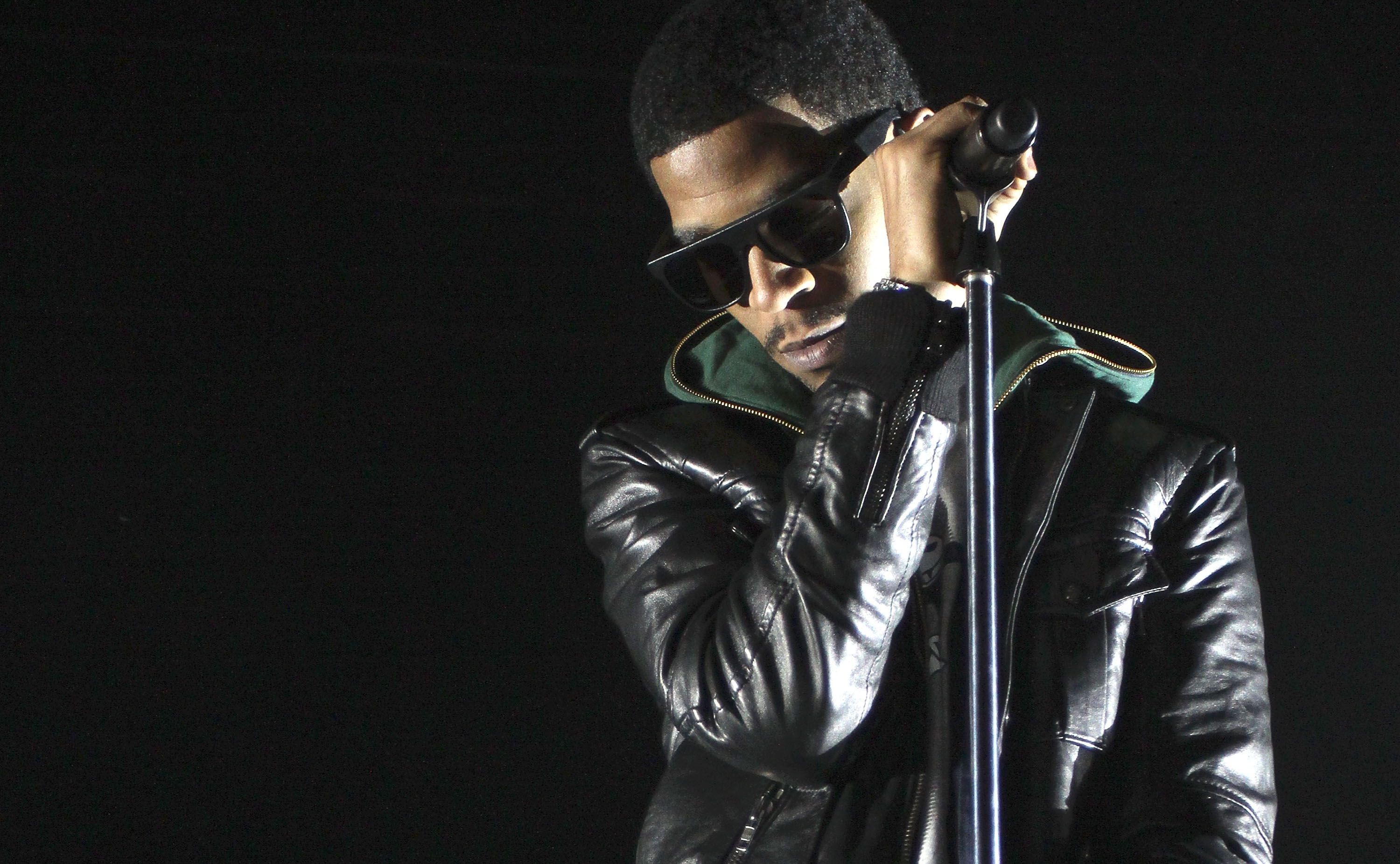

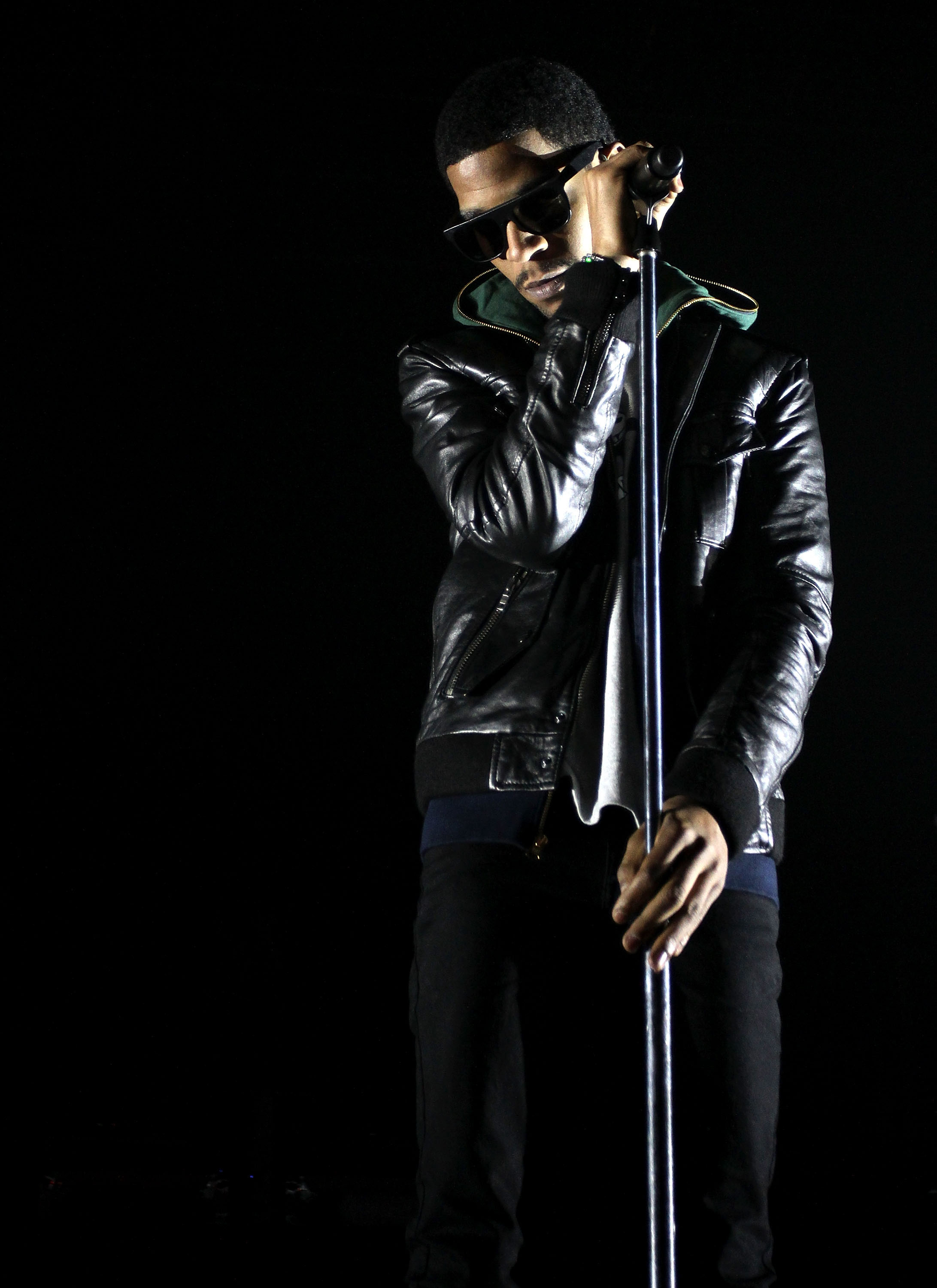

Kid Cudi twirls a neon-red, Darth Maul-style, double-bladed lightsaber skyward, and then catches it, mid-spin.

“I need this on tour, so when motherfuckers run up, I can just be, like, ‘Breach!’?” He twists his head around and shoots me a devilish look.

Dressed this August afternoon as casually as one can be wearing black leather pants and a gold Jesus piece pendant, Cudi, 26, is hanging at home, a sparse, high-ceiling loft in Manhattan’s tony TriBeCa neighborhood. But the reference to defending himself is not quite a joke.

Last December, onstage in Vancouver, Cudi picked up a wallet, thrown from the crowd, that he claimed had struck him square in the face. Irritated, he pointed out who he thought was the wallet’s owner, a fan named Michael Sharpe, and tossed it to him. But the billfold didn’t belong to Sharpe, so he tossed it back onstage. Cudi then leaped over a barricade and confronted Sharpe, who was smiling, thrilled to be face-to-face with an artist he admired. Misinterpreting the smile, Cudi popped the fan in the right eye. A frenzy ensued, bouncers lunged, and moments later Cudi dropped the mic and left. It’s all on YouTube, for posterity.

Then, something unexpected happened. Sharpe told TMZ the next day: “I’m not upset, I’m not going to be that person. I just want to meet him and be like, ‘I’m the guy you punched.’ I’m not going to press charges.”

Five months after the incident, a regretful Cudi brought Sharpe onstage at Seattle’s Sasquatch Festival during the song “Pursuit of Happiness.” Afterward, the two had pizza at Cudi’s hotel. “We’re good friends [now],” he says.

Typical Cudi. He’s a star in the traditional sense—handsome, styled just so, a bit of a prima donna. But he carries a tidal wave of insecurity and empathy with him. It’s a vulnerability, uncommon in the preening world of hip-hop, that has made him an avatar for young, plainspoken dysfunction. And despite, or in part because of, these genuinely distressed emotional flare-ups, Kid Cudi has exceptionally loyal fans.

“At least 104,000,” he says, leaning against a Bape pillow on a sectional couch and taking a pull on his third weed-filled Swisher of the day. The number becomes a sort of mantra during our interview. Actually, it’s the number of copies sold (104,419 exactly) of his debut album, Man on the Moon: The End of Day, in its first week of 2009 release, good for a No. 4 debut on the Billboard chart.

Most of the sales were propelled by breakout single “Day ‘N’ Nite.” Even now, nearly three years since it was recorded and four since it was written, the song sounds like an alien outlier. It’s all bloops, astral synths, and a remarkable half-sung melody—“The lonely stoner seems to free his mind at night.” Like some evolutionary strand of new-age rap, it became a rallying cry for the disaffected and depressed. When the Italian duo Crookers’ electro-house remix hit in late 2008, a swarm of antic, active fans—many in Europe—bought in. Jim Jones, Trey Songz, Pitbull, and many others recorded their own versions. The song has sold an astonishing 2.3 million digital singles.

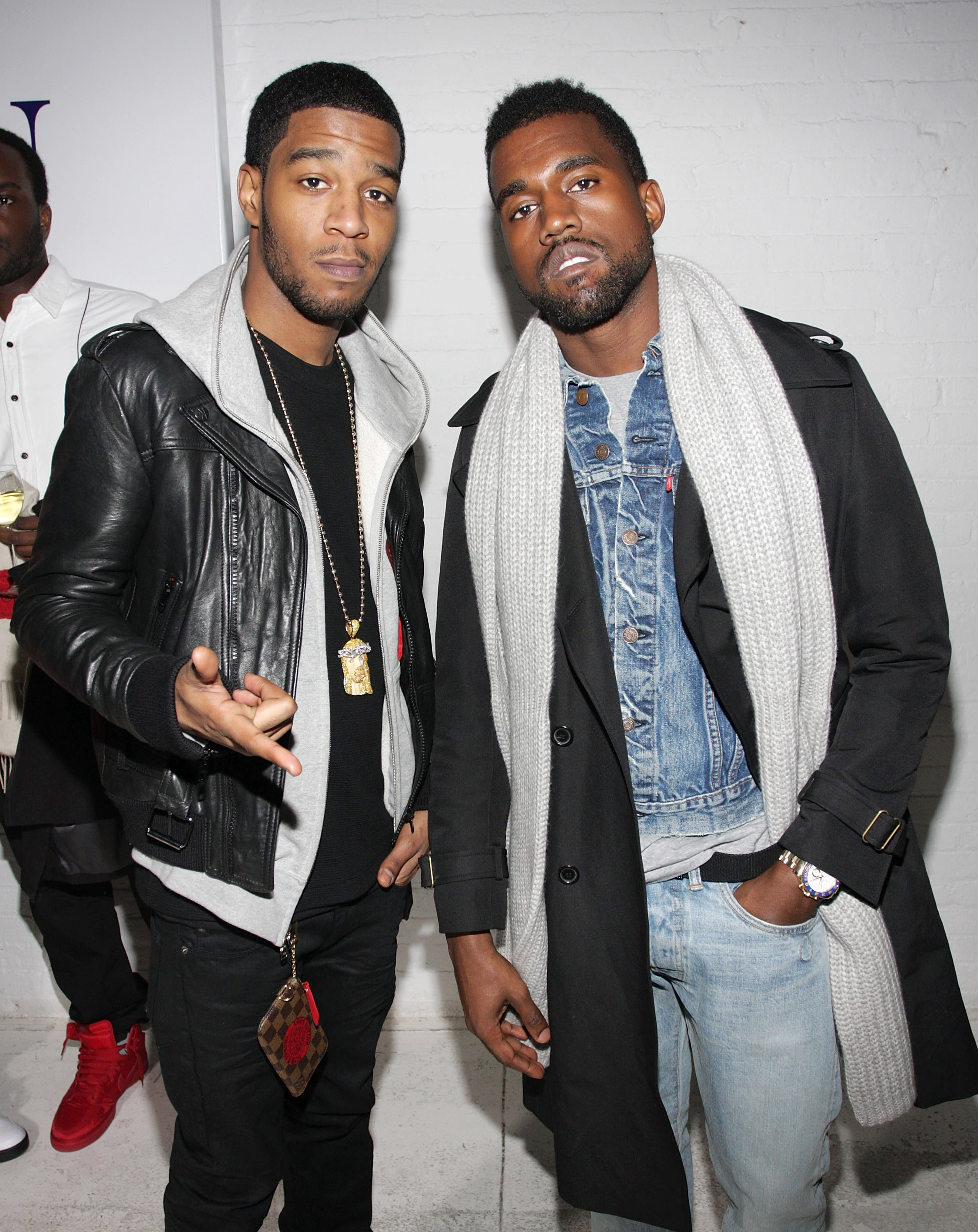

Despite concern from his co-managers—Patrick “Plain Pat” Reynolds, a longtime Kanye West affiliate, and producer Emile Haynie, the rapper’s primary musical collaborator—Cudi hasn’t been haunted by the shadow of “Day ‘N’ Nite.” “I think he knows he’s a star now,” Haynie says. “But before we put out the first album, to a lot of people he was just the ‘Day ‘N’ Nite’ guy.”

In fact, the first thing Cudi wants to do when we sit down is play a song he’s just recorded with “Day ‘N’ Nite” producer Dot Da Genius that he’s hoping to squeeze onto his new album, Man on the Moon II: The Legend of Mr. Rager, before deadline. It might be called “Not That Bad,” but it’s unfinished. As the swaying, sunken beat begins, Cudi taps his retro Air Jordan IV Pure Money $ sneakers on the floor.

The chorus is simple, but considered: “I’m not that bad at all / When you think of the world / It’s not that bad at all.”

Anyone who has followed the problematic aspects of Cudi’s life to this point—his struggle with drugs, his violent outbursts, a recent arrest—will understand why he’s giving himself (and everyone, really) a pass. He has to. It’s the only way to keep the doubts from consuming him.

Born Scott Ramon Seguro Mescudi in Cleveland, Kid Cudi was raised in a lower-middle-class area of Shaker Heights, along with three siblings, by his elementary-school-teacher mother, Elsie, and, until he was 11, his father, Lindberg, a World War II vet and house painter, who died of cancer at 67 in 1995.

“Lin was always a strong force in their lives, and when he got sick, they went through that sickness with him,” says Cudi’s mom of her children. “They were there every day after school, even when it got real bad. So it was a devastating time for all of them—Scott especially, because he was the baby. There’s a sadness [in him] because of the void.”

His father’s passing, though, also spurred Cudi’s creativity. After catching him singing under his bed one day, Elsie pushed him to join the school choir. She bought Calvin and Hobbes anthologies to encourage his drawing. And when he took a serious interest in rap, she supported that, too. Still, the quiet melancholy never disappeared. After being “a C and D student with a teacher mom,” Cudi enrolled in Toledo University, only to drop out after a year studying film.

But he was also recording demos, funded by shifts at a local Applebee’s. While we’re talking, Cudi excitedly rummages through a stack of scratched-up CD-Rs, pulling one out that says KID MESC: RAP HARD with three different Ohio phone numbers written in black marker. This is his first demo, from 2001. He slides it into his MacBook, begging not to be judged. “I’m nervous, man!” There’s shoddy, chipmunk soul-style production and a rickety, East Coast-influenced flow, but it’s Cudi all over.

“I been drunk before, but I’m feeling this shit / I’ve been high before, but I’m feeling this shit,” he raps on “Party All the Time.” When the song is over, Cudi realizes it’s not so bad. “Man, I might redo this and release it!”

After leaving Cleveland in 2005, he moved in with his uncle, the accomplished jazz drummer Kalil Madi, in the South Bronx. He had $500, no job, and no friends. He worked at a couple of Manhattan clothing stores, before eventually sharing an apartment with Dot Da Genius in Brooklyn, and the two began developing the Kid Cudi sound: an atmospheric take on melodic rap, with a dollop of charming, off-key singing. In 2006, while Plain Pat was an A&R at Def Jam, a producer brought Cudi up to the office. They played music and Pat quietly nodded his head. No deal was consummated, but they kept in touch.

“When you meet artists, you know,” Pat says. “Their presence, they’ll take any attention in the room—he did that. He’s always had that star quality. It was just rough.”

After running into Cudi at a club, Pat introduced him to Haynie, who had done production work for Eminem, Ice Cube, and Ghostface Killah. The three quickly became artistic and business partners, and extremely close friends. Sometimes it can feel like two concerned parents struggling with their charismatic ADHD son, but there’s an endearing connection. All three men wistfully recall the early days of touring, playing clubs in Philadelphia and Toronto before fewer than 200 people, earning little money but staying out all night.

“That’s the best time,” Pat says. “The come-up.”

When “Day ‘N’ Nite” took off online, Cudi signed a deal with Kanye West’s G.O.O.D. Music and then with Universal. But before the album’s release, he made a fateful trip to Hawaii to work with West on a Jay-Z album. “I was so nervous, but not typical butterflies,” he says. “Like, ‘Man, I hope this nigga don’t think I’m wack.’ ‘Cause he’ll say this shit’s weak. And I won’t be mad, I’ll be like, ‘You right.’ But I hope he sees what I see. What my mom sees.”

Cudi only landed one song on The Blueprint 3, the sneakily brilliant, “Already Home.” But four of his frozen-hearted hooks found a home on West’s 808s & Heartbreak, also recorded in Hawaii, an album deeply indebted to the sound that Cudi had been building.

“There was something in the room, and everybody was consuming the inspiration,” he says, hesitant to take too much credit.

Cudi is fidgety but funny in person, using goofy voices and playing different characters as he tells stories. But he’s also deeply sensitive, and can be brutally honest in his lyrics, rhyming about the impact of his father’s death, his mother’s financial struggles, and how he had contemplated suicide.

That honesty—coupled with an aspirational slacker attitude and a fashion-forward sensibility—has made Cudi uniquely marketable. His early association with Tape (he once worked in a store) certified him with the streetwear set. Heineken, Vitaminwater, and Converse have used him to promote their brands. But despite all that’s riding on his career, he’s still unguarded about the bad decisions he’s made.

“I started doing drugs to get through interviews,” he says, frankly, his brown eyes unflinching. “Because when people started asking a lot of personal questions about my childhood, I found it terribly hard. So I started doing cocaine to be more upbeat. I’d do bumps and smoke [weed], so I wouldn’t be so edgy. I didn’t know people would be like, ‘So, what was it like when you lost your dad?'”

His growing fame unnerved him. “Have you seen Inception? It’s like, everybody’s a projection. Everywhere I go, I’m like, ‘Why am I in this dream?’ It’s like I’m trespassing in this world that’s not my own. And I was so, so, so wanting to keep it together. That’s what made me do drugs.”

Cudi’s drug use has had severe consequences. “I might not have been shooting up or slangin’ on the block,” he says, “but real life is real.” When I ask him at what point he realized the damage he as causing, Cudi pauses for a full minute.

“After I went to jail.”

On June 11, Scott Mescudi was arrested on charges of felony criminal mischief and possession of a controlled substance (alleged to be liquid cocaine in a small glass tube). Reports say that he smashed the cellphone of a 24-year-old woman—thought to be his girlfriend, Jamie Baratta—and ripped an apartment door off its hinges.

“If I’m gonna be going to jail, I’m not gonna be doing this no more,” Cudi says, adopting a childlike voice, masking the incident’s seriousness. “I had a newfound respect for T.I. and [Lil] Wayne. I only spent 15 hours in there! I was scared straight, going through the shakes, having no food, being held captive. It didn’t matter who I was in the world.”

Man on the Moon II reflects these complications in his life. The songs are visceral, with audible coke sniffs and lyrics detailing debauched nights with women. “It’s a chapter of my life I’m closing,” he says. It’s meant to be a cautionary song cycle—”for those for whom cocaine does not work.”

At times, the album name-drops affairs that feel too close to the flesh. On “Mojo So Dope,” Cudi raps, “Wish that I could tell my brother / Something for some motivation to get him out that gutter / He’s leaving behind a family and a mother / Damn, you must understand what I speak about in song is how I really am / Yeah, this is how I really think / You can see what I see / Yes, I really think / Yes, I really drink, I really do rage.”

You can see remnants of this Kid Cudi, the album’s titular rage, on the HBO series How to Make It in America, as his character, Domingo Brown (who shares a name with Cudi’s own brother), romances models and tips back bottles of brown liquor. But Cudi’s real-life learning curve is bending in a shockingly short period of time. In March, his daughter, Vada Mescudi, was born; her mother is a longtime friend/ex, and immediately after our interview, he’s airport-bound, headed back to Cleveland, where mom and Vada live.

“Trying to grow and be a better man, take care of my responsibilities while not being around [my daughter] fucked with my head,” he says. “But I’m going to see her today.”

He seems content, reclining in his hipster palace, but still caught between responsibility and fleeting youth. “You know, in order to be a Jedi, you need to go though some real training.”