This article originally appeared in the February 1997 issue of SPIN.

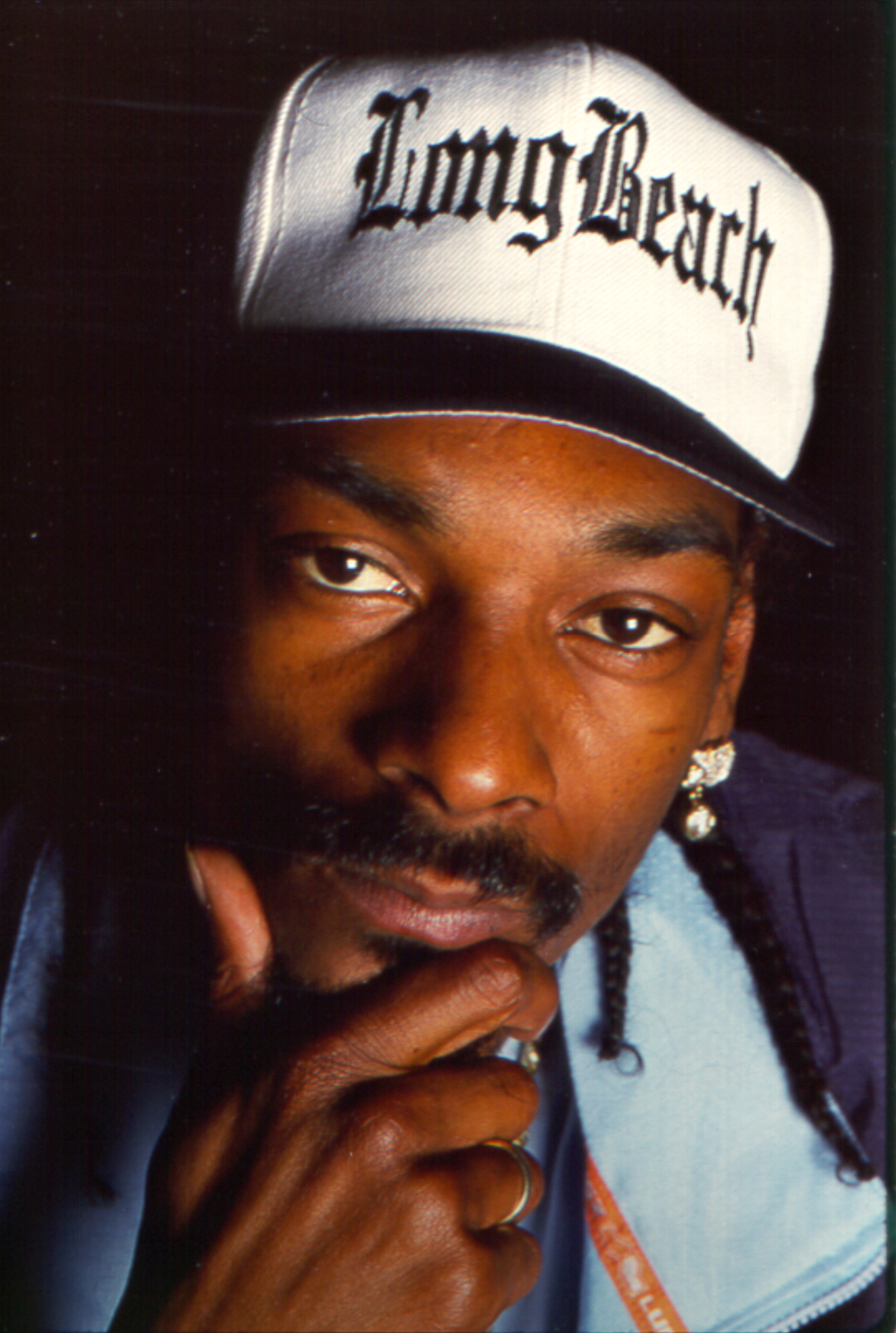

Imagine you are Snoop Doggy Dogg, the best and biggest-selling rapper of the ’90s, hero to millions of kids. It’s less than a week before the release of Tha Doggfather, your first real album in three years, a cinch to go No. 1, but still you are maybe the fifth most interesting thing going on in that maelstrom that surrounds you.

Marion “Suge” Knight, Jr., the currently imprisoned president of your record company, is getting 20 inches in the newspaper every morning on trumped-up allegations of probation violations, coziness with the D.A.’s office, implied racketeering investigations, and whatnot. Your childhood buddy, gangsta crooner Nate Dogg, whose own album is about to come out, is regaling the media with stories of his own dramatic acquittal—he was accused of holding up a Taco Bell.

Record mongul and Death Row rival Sean “Puffy” Combs told the Los Angeles Times that if hip-hop is a church, your old partner Dr. Dre was God. And your late colleague Tupac Shakur is being hailed as the most important rapper of your generation—2Pac!—partially because he managed to leave his hardcore gangsta throwdowns with a couple of sweet songs about his mama, but also because he’s dead. Shakur was your friend, and you thought he was the bomb, and you dedicated your album to his memory, but still…

The Wednesday before his album is due to come out, Snoop, 25, is camped out on a nonsmoking floor of the Four Seasons Hotel at Beverly Hills, trying to explain hip-hop to a stringer for the second biggest music magazine in Iceland, a guy with probably more direct experience with elephant seals than with the world Snoop grew up in.

The sweet, oatlike stench of skunk weed penetrates all the way to the gilded marble lobby. Coolio was there earlier, natty dreads pointing randomly toward the four corners of the room, and so were Nate Dogg and the Dogg Pound’s Dat Nigga Daz and a perpetually smiling friend of Snoop’s who is in the habit of carrying around big, lavishly chromed radio microphones that don’t happen to be plugged into anything.

His publicist, George Pryce, had been there, and a Norwegian woman who had something to do with international press and interlocutors from Germany and Sweden and France, all asking, in the politest possible fashion, whether Snoop was a Crip.

Finally, they are all gone—Iceland, too—and Snoop drifts off on the hotel-room bed, and the Lakers are getting shellacked by the Hornets on the big-screen TV.

There are certain self-reflexive things that any gangsta rapper will say, and Snoop Doggy Dogg (real name Calvin Broadus) is no different. Like a senatorial candidate, he is adept at staying on subject. If you ask him about certain lyrics, he’ll say he’s just talking about the “bitches” and “ho’s,” not all women. (Tha Doggfather even includes a paean to large women salted into his version of a Too Short pimp rhyme.)

If he is asked about violence, he’ll say his lyrics reflect the realities of the streets, and that whoever doesn’t like it might well consider the problem of urban joblessness. He’ll admit his music is too intense for children (though he contemplates an album with no swearing on it), and he’ll confess that some things are just too dope for some people to hear. He will point out that nobody is holding a gun to anyone’s head to make him or her buy a rap record.

Snoop Doggy Dogg, though, isn’t just any gangsta rapper. He is an artist. Snoop settles into a groove like Miles Davis, his buttery, distinctive tenor oozing onto looped beats. The glottal stops, the croon, the softly swallowed Mississippi diphthongs of his voice are as flexible as some marvelous instruments suddenly given the dead-quiet power of Black American speech. Snoop’s voice is especially compelling when half-buried under the eerie beats, the sights, the soul moans, and the endlessly pounded minor-key riffing that forms the soundtrack to the Doggy Dogg world.

Fans of G-style rap—and I count myself among them—would pay good money to hear Snoop freestyle over a groove laid down by, I don’t know, Kenny G. But here is the dilemma: Snoop, this slim musician sunk deep into a hotel-room bed, the best rapper in the world and, not incidentally, a guy acquitted of murder, is the punch line to the jokes of a hundred late-night comedians, a poster boy for violence in mass entertainment, and—if you can believe Bob Dole—a proximate cause of America’s moral decline.

“There ain’t nothing a young man can do,” Snoop says, “to prepare himself for the hell I’ve gone through. I’m living positive. I’ve been through jail. I’ve been through selling drugs. I’ve been shot at. But I’m just as cool as ever. I don’t understand the big misperception that people feel I’m a villain or something—I’m no sort of roughneck. I’m a smooth macadamian.”

Snoop closes his eyes, and nods off to sleep.

A few months before this we’re at Can-Am, a recording studio in a dusty corner of the San Fernando Valley that, until Death Row’s recent troubles, was the Abbey Road of gangsta rap. Snoop has his eyes closed, but his famously long lashes throb to something that sounds like an old Gap Band beat, and his lips move a little as he tries to work out a verse for the Persian-disco-flavored song that will end up as the title track and the most distinctive song on Snoop’s achingly conventional Doggfather.

A messenger shows up with some wings and fries—sometimes at Can-Am on of the original Brides of Funkenstein, now a backup singer with Snoop, will barbecue some hot links—and business in the studio grinds to a halt. “I could sure wrap my stomach around some of that,” Snoop says, then disappears with the bucket into the next room.

The producer L.T. walks over to the table where Snoop has laid out a fat joint he’d lovingly rolled around the foliage of a glistening green bud, and he pretends to sweep the weed into his pocket.

“Let’s see if he forgets,” L.T. says. “I bet if we clear this off, nigga will forget about it and roll himself another one.”

“Bet,” says Daz. “Some things, Snoop never forgets.”

“I don’t know about that,” says a skinny engineer, and suddenly everybody has plucked bills from their wallets, calculating odds, ready to bet on Snoop as if he was a pit bull in the ring or a pair of dice destined to roll six the hard way.

L.T. reaches for the weed, but before he can hid it, Snoop sweeps back into the room, heads straight for the table, and lovingly fires the fattie into sputtering life. A dozen wallets slide back into hip pockets and the room resonates with something like a groan.

Snoop exhales enough smoke to give all of Woodland Hills a potent contact high. “I knew there was something in here I forgot,” he says.

We are in the office of Sharitha Knight, Snoop’s manager and, as it happens, the wife of Death Row’s capo Suge Knight, who bears a thick sheaf of contracts for Snoop to sign. (In hip-hop, this suspect commingling of business relationships is not unusual—Russell Simmons managed most of the artists on his label Def Jam; Jerry Heller managed proto-gangstas N.W.A. while managing their label, Ruthless.)

One guy walks around the office wearing a giant, leering dog head on his shoulders, apparently as a sort of spec-effort for Snoop’s stage show. Snoop himself is done up a little today, wearing Pippi Longstocking pigtails, a Ken Griffey, Jr., Seattle Mariners jersey, and a pair of Converse that look a little like pristine white dodgem cars.

“I paid for these myself,” says Snoop a bit incredulously, thrusting a foot Jackie Chan-style into Sharitha’s face. “Can we hook something up with Converse—these shoes are tight.”

But the subject for today is politics. Snoop wants to run for president, and he is touchier than Ross Perot. “The thing is,” Sharitha says, “you can’t really run for president.”

“I can be a write-in candidate,” Snoop says.

“You can encourage 18-year-olds to vote,” Sharitha says, “and you can ask people to vote for—who do you like, Clinton?—but politicians like Maxine Waters have said a lot of nice things about you, and if you mock what they do, they can’t help you any more.”

“But I wasn’t going to just clown it,” Snoop says. “I’ve got things to say. And you’ve got to be 35 to be president, and it’s not like anybody thinks I could be winning even if I were old enough. ‘What is this nigga doin’ trying to be president?'”

“I understand what you’re talking about,” says Sharitha. “You can’t be president because you literally don’t…”

Snoop looks up at the ceiling and mumbles a silent prayer. “Woo woo woo,” he says. “I have a felony. I’m a black man. I smoke weed, and I inhale like a motherfucker. Maybe if you vote, you can just get a dollar off on my album or something.”

“Exactly,” says Sharitha. “You can say you’re the President of Rap.”

“That would be ay-ight,” says Snoop. “I could get that East Coast/West Coast bullshit stopped, get the most powerful rappers from the East and get a peace treaty going. We could get into the studio together and show the world that black men can pull together for peace. Then we can move on and make some money.”

If you’d happened into a recording studio a few years ago when Snoop was recording with Dr. Dre, you would have witnessed the electric, wordless communication behind one of the most remarkable collaborations in rock’n’roll history, a funky hip-hop creature with two distinct heads and a single, monster beat.

“You don’t need no more rap on that song, Dr. Dre,” cried Snoop when he finished a take. “Now there’s some tight-ass conversation at the end.”

The story of Snoop and Dr. Dre is legend by now. Snoop had been in a rap group, 213, with Nate Dogg and Dre’s little brother Warren G, who would later score with his song “Regulate.” Warren slipped Dre a copy of a 213 tape at a bachelor party, and Dre invited Snoop to hang around the studio around the time he was working on the second N.W.A. album. Snoop rapped on Dre’s theme song to the Laurence Fishburne vehicle Deep Cover, and Snoop’s singsong chant of “1-8-7 on a undercover cop” propelled the song to No. 1 on the rap charts in 1992.

Soon after that, Snoop wrote about two thirds of the words to Dre’s album The Chronic, and helped introduce the concept of indo, Gs, and bitchez to 13-year-old kids in Arkansas. Dre produced Snoop’s album Doggystyle, which sold five million copies. Dre and Snoop were Lennon and McCartney, Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson, Eric B & Rkim. And then this year, Dre left Death Row to start his own label, Aftermath, and his collaboration with Snoop came to an end.

Snoop did most of Tha Doggfather with his cousin Daz from the Dogg Pound producing, or L.T., or Dre-soundalike Sam Sneed, or DJ Pooh, whose hard-edged beats have powered Ice Cube’s rhymes for years but who is perhaps most notorious in the rap community for the raw-and-ready commercials he produces for St. Ides Malt Liquor. (Snoop is set to endorse a new blueberry-flavored malt liquor for the company.) Tha Doggfather has some decent flavors on it, most prominently the buzzing bottom provided by the Gap Band’s Charlie Wilson, which works nicely with Snoop’s floating rap style. But still—there’s not Dre.

“Too much talent on one team can be bad,” Snoop says. “There’s just so much dopeness you can put on a record, and when everyone becomes such a superstar, they don’t listen any more: ‘Motherfucker, I sold three million records. You can’t be telling me what to do.'”

“I still want to work with Snoop again someday,” says Dre in the office of his own San Fernando Valley studio, scant minutes after improvising a new ending for the radio version of his “Been There Done That” single. “But to be perfectly honest, I don’t like Snoop’s new album. And it has nothing to do with me not working with him, because I’m just like anybody else: I like it, or I don’t.”

“The first time I heard the single, I was grooving to it, but then I really started to get into production and how it was sounding, you know? The first time you hear some shit, you just listen to it to get your groove on, but after that, I started breaking songs down. There’s really nothing that was said on there that hasn’t been said 50 times before.”

These days, Snoop and Dre barely even talk on the phone: Snoop is hurt that Dre never turned up to show solidarity at his trial; Dre is, y’know, busy. At Can-Am, when Snoop runs into a friend he hasn’t seen in a couple of months and they settle down to gossip about Dre, Snoop learns more than he betrays.

“I asked Dre to call me,” says the friend, “and he was like, ‘Why?'”

“I’m not saying he has to be jocking me up,” Snoop says, “but…”

“He did say he’d work on your stuff…”

“But he wasn’t enthused,” Snoop says. “It makes me think that the niggas I got with me is pumped up to be working with me.”

“Dre’s married now,” says the friend. “I think that girl does a lot to him.”

Snoop takes a step backward. He hadn’t known. “He’s got a ring on his finger?” he says.

“They got married in Hawaii,” his friend says. “I hear she’s got him twisted up.”

“She tripped on us,” Snoop says. “She had the house taped off like someone got killed there or something, yellow police tape.”

“She only wants people in certain areas,” his friend says. “And she doesn’t want the music played loud.”

“Oh, that’s nasty,” Snoop says. “But still. I told him, I’ll still give you some weed, I’ll still write [lyrics] for you, just look out for me on my album. And he was, like, putting me off and shit.”

“I don’t know, Dogg,” his friend says. “It sounds like he’s fucking up. He’s tired of the street shit. How many platinum albums does he need?”

“But you know something?” Snoop says. “When he retires, he’s going straight to the hall of fame.”

The first time I talked to Snoop, on a hot afternoon in August 1993, was in a recording studio in the deepest Valley, a swank place with platinum Michael Jackson records on the wall and a locked parking lot brimful with Ferraris. I was there to interview Dr. Dre, who was then producing Snoop’s first album, and I spent several hours talking to Snoop, who at that point seemed as proud of the clean time he’d served in jail as he was of the songs on his new record. Then, a couple of days later, Philip Woldemariam was killed, and Snoop’s life would never be the same again.

Palms is a part of Los Angeles sometimes known as the entry-level Westside, a neighborhood densely built up with two-story apartment buildings—local architects call them “dingbats”—popular both with recent UCLA graduates and with former inner-city dwellers drawn to the area’s good schools, clean air, and relatively safe streets.

In the fading light of a hot afternoon in late August 1993, Philip Woldemariam, Jason London, and Duchaun Joseph, members of a local street gang, bought some takeout food at a Palms Mexican restaurant, and started to drive a few blocks to Woodbine Park. They’d never finish their burritos.

One the way to the park, the three passed a group of people hanging around outside an apartment building on Vinton Avenue. Everyone in the neighborhood knew a record company had rented apartments in the building for Snoop Doggy Dogg and his bodyguard Malik (a.k.a. McKinley Lee) to live in while Snoop finished Doggystyle in a nearby studio—the Dog Pound, everybody called it. When they passed by, hoping to catch a glimpse of the rapper, Woldemariam thought he saw somebody on the sidewalk flash a gang sign.

“They hit me up,” he said, and told Joseph to the back up the car.

Woldemariam leaned forward over London from the back seat and poked his head out the front passenger window of the car. “Whassup!” he spat. “Where y’all from?” By this he meant, “What gang do you represent?”

“Long Beach Insane,” replied a person on the sidewalk, referring to the neighborhood Snoop and many of his friends were from.

“This is Vinton Ave.,” Woldmariam said, asserting the turf of his own gang, the Vinton Avenue By Yerself Hustlers, which included this area around Woodbine Park.

“Y’all shouldn’t do that,” said the man on the sidewalk.

Woldemariam’s voice almost vibrated with anger. “Fuck y’all,” he said, resorting to the deadliest insult in the gangbanger’s canon. Snoop and his bodyguard Malik came down the stairs of the apartment building to check out the scene. A gun dangled at Malik’s side.

“Bone out!”—leave!—London said, and Joseph drove away fast down the street. A few seconds later, Woldemariam noticed that their car was being followed by the black Jeep Cherokee that had been in the driveway of the apartment building. Joseph made a few evasive turns, and the driver of the Jeep evidently tiring of the chase, turned off.

As the three sat in the park later, eating their burritos around a picnic table, they again saw the black Jeep, driven by Snoop Doggy Dogg, rolling very slowly by. Woldemariam walked toward the Jeep, came within a couple of feet of it, then passed behind the vehicle and walked across the street. He grabbed a stolen .38 automatic belonging to Joseph from where he’d stashed it in some bushes, stowing the gun in his waistband. When the Jeep drove by again, Woldemariam leaped onto the picnic table and yelled “Whassup!”; he thrust up his arms in what could be construed as a come-and-get-it gesture. The Jeep stopped, almost in the middle of the street.

Woldemariam strode up to the Jeep, ignoring London’s attempts to stop him, and the vehicle’s rear window rolled down. “I’m not trying to sweat y’all,” Woldemariam hissed. “I’m just letting you know where you’re at”—whose territory you’re on.

“You’re not letting us know nothing, punk,” somebody, probably Snoop’s friend Sean Dogg, said from the back seat.”

“I’m a punk, am I?” said Woldemariam. He lifted his shirt and allegedly reached for his .38, but Malik’s karate-honed reflexes were too quick, and the bodyguard emptied his gun before the local could squeeze off a single effective shot. Woldemariam’s friends dove to the ground. Woldemariam ran away, stumbling, and the Jeep roared off before anybody in it knew whether he had been shot. He had.

The fatal bullet passed between the 11th and 12th ribs of Philip Woldemariam’s body, bored through a kidney, and perforated his aorta, diaphragm, and right lung before coming to rest against his fifth right-posterior rib. Woldemariam bled to death in a carport across an alley from the park as his friend London cradled his head in his hands.

As badly as the prosecutor on the case, a prim, youngish deputy D.A. from the Hardcore Gang Unit named Edward Nison, seemed to want to put gangsta rap on trail, the judges wouldn’t allow him to do so in the courtroom. At a preliminary hearing in September 1993, Nlson unsuccessfully attempted to get Snoop’s bail revoked, arguing that the rapper was making money “promoting a lifestyle whose upshot is at the center of this case.” At a pretrial hearing in Superior Court Judge Paul Flynn’s courtroom, Nison quoted lyrics from Snoop’s “Murder Was the Case,” and the judge rolled his eyes.

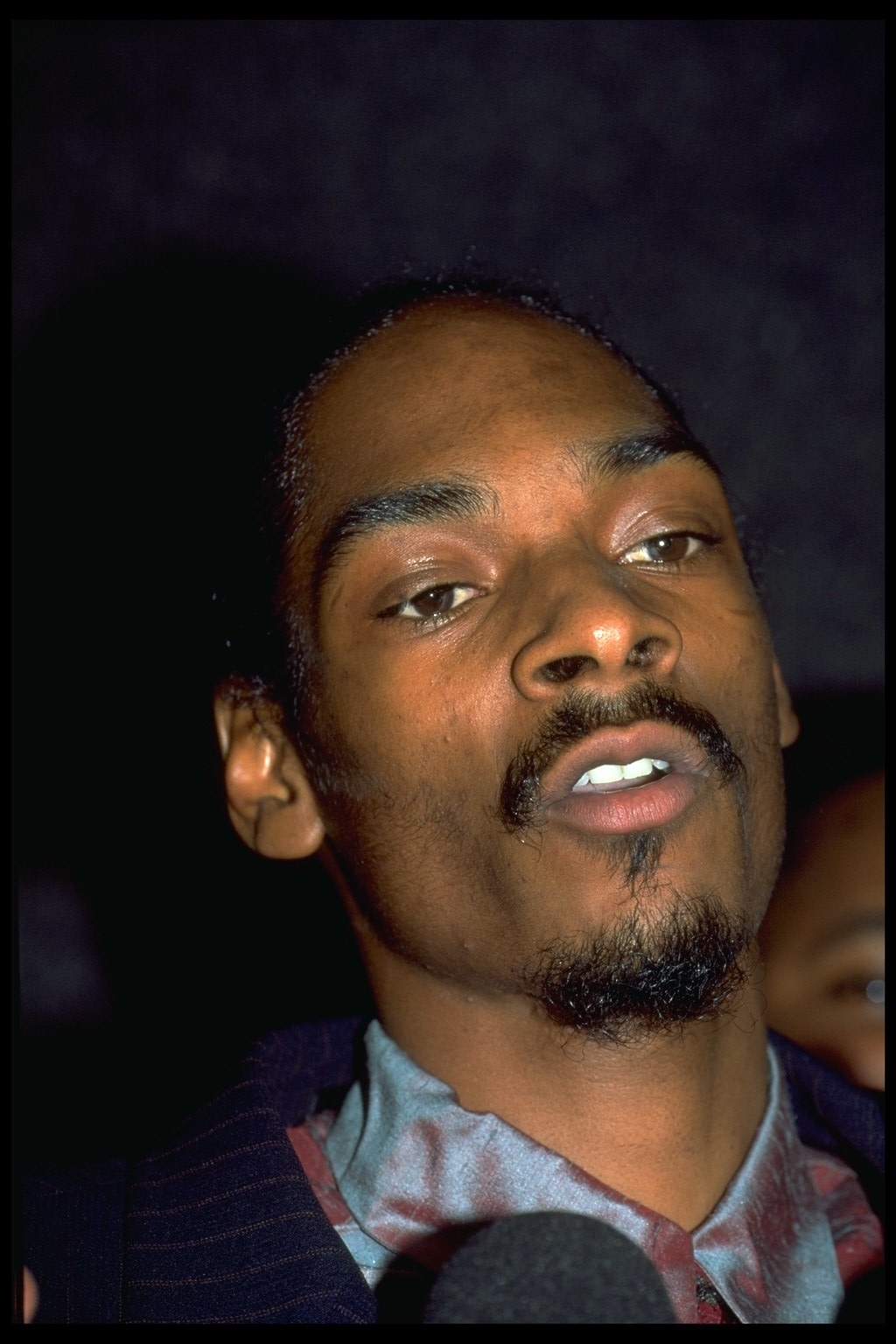

The Snoop Doggy Dogg who finally came to trial, two and a half years after the incident, was a neat, soft-spoken young man who wore his hair pulled back into a tight braid and had a thing for Armani suits and two-tone ’30s saddle shoes. It would have taken a bit of work to imagine him as the feral, wild-eyed ghetto avenger his lyrics sometimes make him out to be.

A week or so into the trial, jurors began to laugh openly at Nison when he accidentally made points for the defense. In the privacy of the jury room, the referred to him as “Biff”—the ultimate white-bread dweeb—and imitated his stiff walk. One juror wrote a mocking rap song, which he later performed to the cheers of the rapper’s friends at a victory party thrown in a Westwood steakhouse the night after the verdict. Bobby Grace, the other deputy D.A. on the team, a young African-American with political ambitions, seemed to wish he was anywhere but in that particular courtroom. After the prosecution finished the case, Snoop’s attorney David Kenner called a single minor defense witness and rested. The prosecution, he said, didn’t have a case.

The closing arguments were much the same as the rest of the case, but Grace’s rebuttal was extraordinary. He compared Woldemariam to the narrator of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and to Bigger Thomas from Richard Wright’s Native Son, thus playing the race card possible for the very first time in a case of black-on-black crime.

His theatrics almost worked: After acquitting Snoop and Malik on charges of first- and second-degree murder, the jury, leaning nine to three toward acquittal, deadlocked on a manslaughter charge. The D.A.’s office elected not to retry the case.

Standing next to the shoeshine stand downstairs on February 20, 1996, surrounded by camera crews, Snoop at least pretended to be ecstatic. “Tonight, I’m writing a letter to the District Attorney,” he crooned. “I’ma tell him, ‘Sorry. You can’t have me.'”

Over the last three and a half years, I have been in proximity to Snoop about a hundred times: in studios, in rehearsal halls, in clubs, and in many, many courtrooms. I was at his church the day he returned as the prodigal son (even his minister calls him Snoop); next to the cameraman when he explained the beauty he’d experienced in the Los Angeles riots for a year-end special on Fox.

I saw him break up a fistfight on a party boat that was described by the nightly news as a floating riot. I’ve met most of his relatives—his mother, his father, his uncles, many cousins, his three-year-old son and his longtime girlfriend Shanté (who looks exactly like his mom)—as well as dozens of his friends and hundreds of his supporters, including the members of R.I.S.E., the gang-unity organization Snoop helps to maintain.

I’ve seen Snoop lay down bits of each of his albums, and I have seen him grow from a young, raw, talented rapper utterly in awe of Dr. Dre, into an artist secure enough in his command to essentially run his own recording sessions; from a kid who said that his hobbies included smoking weed and Cripping to the acknowledged leader of the artists on the most successful small label in the world.

But the thing I have learned most about Snoop over the years is the difficulty of knowing anything at all about Snoop: Is he the voice of his generation or a lucky version of the amiable stoner in the back row of your algebra class, a cartoon character or a powerful communicator, murderer or victim, Calvin Broadus or just Snoop? As with those other great pop ciphers Madonna and Michael Jackson, what you think about Snoop may say less about him than it does about you.

“It’s cool being a mystery,” says Snoop Doggy Dogg.