This article originally appeared in the September 1988 issue of SPIN.

It was an old-style protest handbill, unsigned, dropped anonymously on every seat at the New Music Seminar’s panel on racism. Across the top, handwritten in artless capital letters, it read “DON’T BELIEVE THE HATE.” And for the remainder of the page, in cramped, single-spaced type, it presented its case:

The World According To Public Enemy:

“Cats naturally miaow, dogs naturally bark, and whites naturally murder and cheat…White people’s hearts are so cold they can’t wait to lie, cheat, and murder. This is white people’s nature….Whites are the biggest murders on earth.”

“There’s no place for gays. When God destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah, it was for that sort of behavior.” (The Face, July/Aug. 88)

“The White Race or the Caucasian Race came from the Caucus mountains…It was not black people who made it with monkeys, animals, and dogs, but it was white people…White people are actually moneys’ uncles because that’s who they made it with in the Caucasian hills.”

“They say the white Jews built the pyramids. Shit. The Jews can’t even build houses that stand up nowadays. How the hell did they build the pyramids?”

“If the Palestinians took up arms, went into Israel and killed all the Jews, it’d be alright.” (Melody Maker, May 28, 1988)

It was July 18, the opening day of the Democratic National Convention, and the emotional circus that had been building around Public Enemy all summer just kicked up a notch. By the time the night was over, and Public Enemy lead rapper Chuck D had denounced writer and supporter Greg Tate as the Village Voice‘s “porch nigger,” New York was swinging. We’d never seen anything like this before.

It was also nine business days after the release of Public Enemy’s second album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, and the record had already unofficially gone gold, sating the very different hungers of black and white audiences. It seemed to be booming out of every car at every traffic light in the city. The Wall Street Journal had recently discovered car stereos that approached the decibel level required to bore a hole in a piece of wood, and this was the perfect program material—dense beats, fragments of sound and meaning, vituperative word-association: “Suckers, liars, get me a shovel/Some writers I know are damn devils/From them I say don’t believe the hype/Yo Chuck, they must be on the pipe, right?”

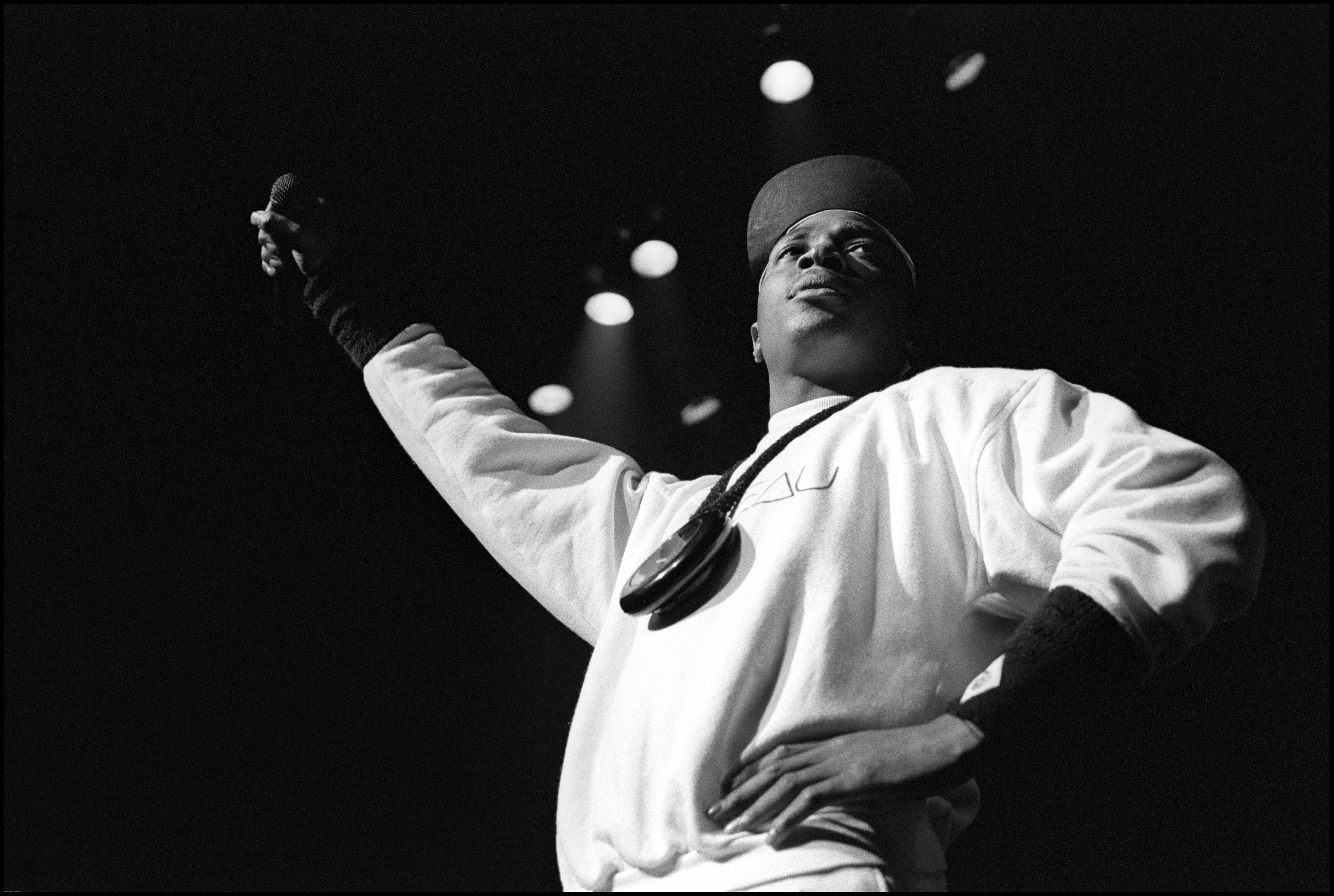

What might have been a simple, bodaciously funky message of black self-determination, delivered by two college friends from Long Island, had turned into a liberal apologist’s nightmare, a martyrdom in the making. At the center of it all, Chuck D, a virtual red diaper baby with a degree in graphic design, compared himself to Marcus Garvey and Nat Turner, and let the contradictions swirl.

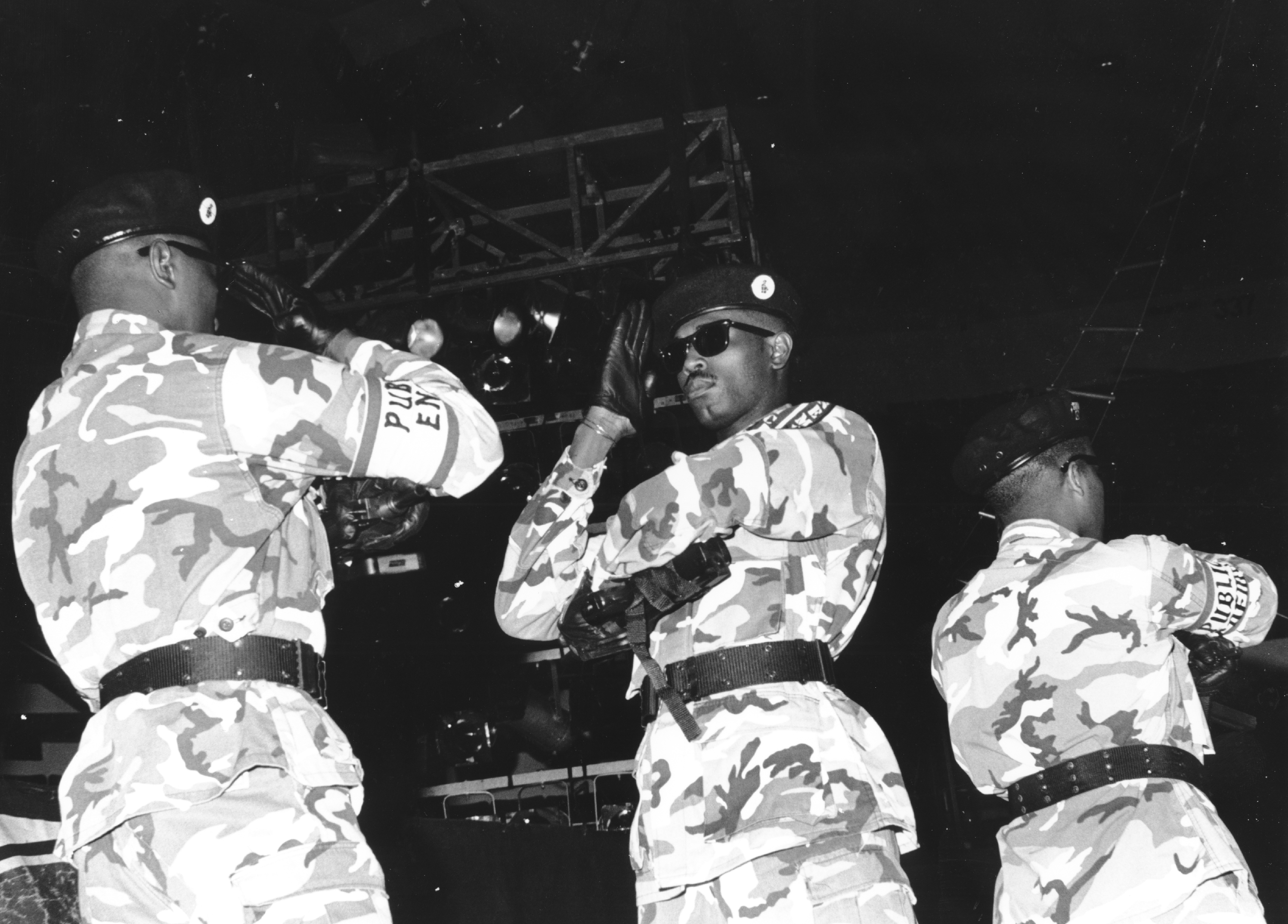

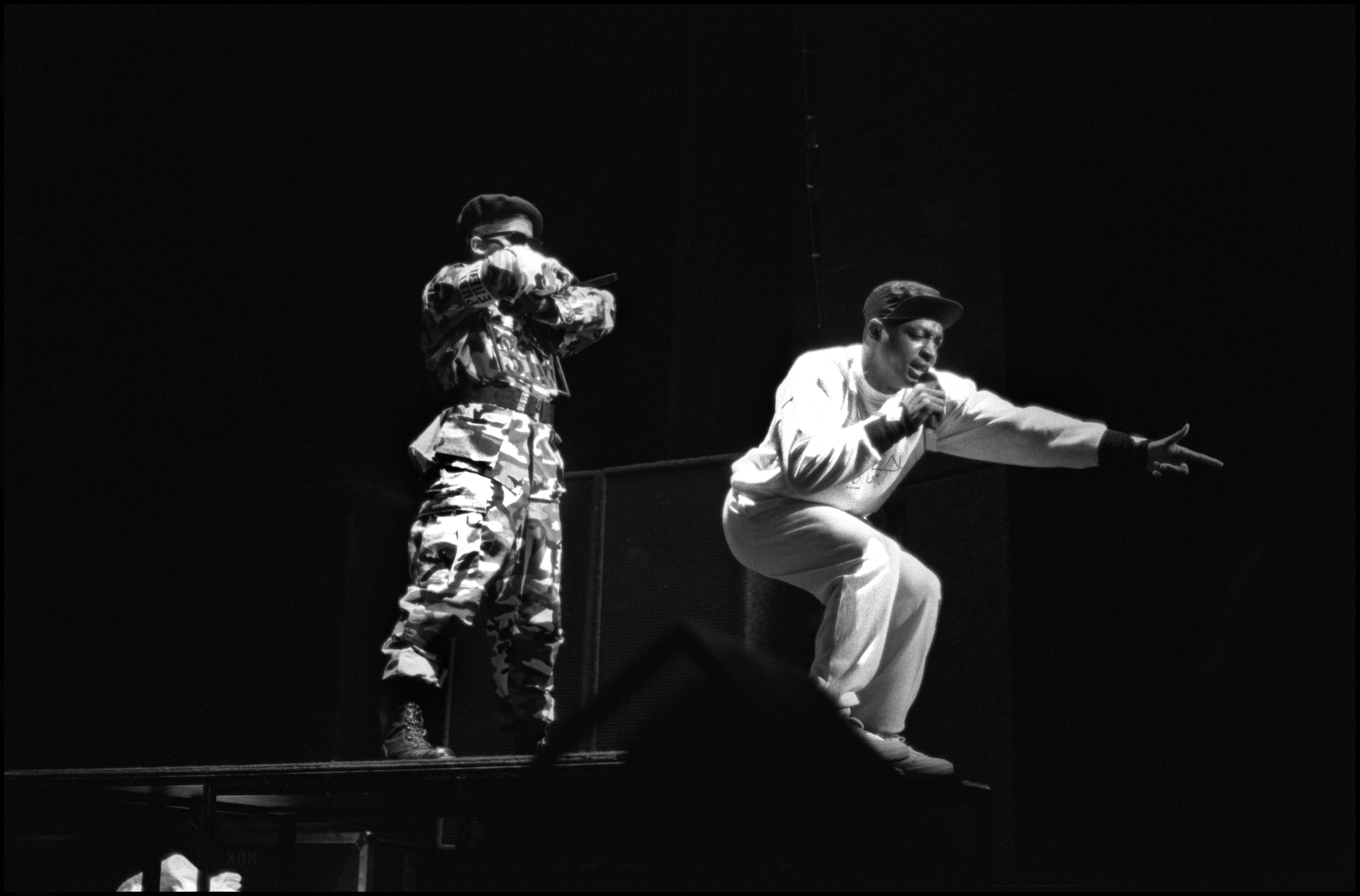

For the record, Chuck D didn’t make the statements quoted in the handbill. They belong to Professor Griff, Public Enemy’s Minister of Information, and leader of the S1Ws (security of the First World), Public Enemy’s plastic-Uzi-toting, paramilitary Muslim security force.

Like Chuck D’s logo, a silhouette of a black youth inside a rifle site, and like the S1W’s plastic Uzis, Public Enemy merges the rhetoric of militancy with that of advertising in ways that sit uneasily for both camps. The crew is both rational and hysterical at the same time. It offers hysteria as a rational response to the times.

Chuck D: “It’s definitely Armageddon. The black man and woman is at war with himself or herself, and with the situation around them. Armageddon is the war to end all wars. That’s when everything hopefully will be alright, the last frontier. Of course we’re in it. I’m in it. Maybe you’re not in it. You can afford not to be in it, because it doesn’t confront you on a daily basis. Black people in America are at war.”

Chuck, what’s your reaction to the handbill distributed at the New Music Seminar?

They’re making a whole lot of shit about nothing. A lot of paranoia going on. People think I got the ability to fucking turn a country around.

Do you back the statements that Griff made?

I back Griff. Whatever he says, he can prove.

You mean he can prove that white people mated with monkeys? That it wouldn’t be such a bad idea if the Palestinians were to kill all the Jews in Israel?

Now that was taken out of context. I was there. He said, by Western civilization’s standards it wouldn’t be bad for the Palestinians to come into Palestine and kill all the Jews, because that’s what’s been done right throughout Western civilization: invasion, conquering, and killing. That wasn’t mentioned.

It’s no secret that white people lived in caves while blacks had civilizations. Marcus Garvey said the same shit Farrakhan’s saying today. Black people know this. White people do not.

Now, people think we’re building up some kind of anti-Semitic hate. Black people’s feelings around the country, 98 percent of them say Jews are just white people, there ain’t no difference. That’s my feeling. I don’t like to make an issue out of it.

Does Griff speak for Public Enemy?

He speaks for himself. At the same time, Griff’s my brother in Public Enemy. People are gonna see that Griff said this, and in the same interview, I said something else. It’s up to them.

Do you consider yourselves prophets?

I guess so. Were bringing a message that’s the same shit that all the other guys that I mentioned in the song have either been killed for or deported: Marcus Garvey, Nat Turner, all the way up to Farrakhan and Malcolm X.

What is a prophet? One that comes with a message from God to try to free people. My people are enslaved within their own minds.

Rap serves as the communication that they don’t get for themselves to make them feel good about themselves. Rap is black America’s TV station. It gives a whole perspective of what exists and what black life is about. And black life doesn’t get the total spectrum of information through anything else. They don’t get it through print because kids won’t pick up no magazines or no books, really, unless it got pictures of rap stars. They don’t see themselves on TV. Number two, black radio stations have neglected giving out information.

On what?

On anything. They give out information that white America gives out. Black radio does not challenge information coming from the structures into the black community, does not interpret what’s happening around the world in the benefit of us. It interprets it the same way that Channel 7 would. Where it should be, the black station interprets the information from Channel 7 and says, “This is what Channel 7 was talking about. Now as far as we’re concerned…”

We don’t have that. The only thing that gives the straight-up facts on how the black youth feel is a rap record. It’s the number one communicator, force and source, in America right now. Black kids are listening to rap records right now more than anything, and they’re taking it word for word.

I look at myself as an interpreter and dispatcher. To get a message across, you have to bring up certain elements that they praise, or once did praise, ’cause I’ve seen a change in the last year and a half.

What do you have to bring up that they praise?

Violence. Drugs. I’ll give you a good case, I’m warming you up, you know. It takes me a while to warm up into an interview. Two years ago black kids used to think that saying nothing was alright; getting a gold rope, a fat dukey gold rope, was dope, was the dope shit; it’s alright to sniff a little coke, get nice for the moment; get my fly ride and do anything to get it, even if it means stomping on the next man, ’cause I got to look out for number one. It’s alright for a drug dealer to deal drugs, it’s alright ’cause he’s making money.

1988, it’s a different thought. Because consciousness has been raised to the point where people are saying, “That gold rope don’t mean shit now.”

Are you taking credit for these changes?

Yes. When I say, “Farrakhan’s a prophet and I think you ought to listen,” [on “Bring the Noise”], kids don’t challenge the fact that Farrakhan’s a prophet or not. Few of them know what a prophet is. But they will try to find out who Farrakhan is and what a prophet is. It sounds good to them at first, then at the same time they’re going to say, “Well, it interests me, let me get into it.” Their curiosity has been sparked. Once curiosity has been sparked, the learning process begins. You can’t teach, or a kid can’t learn, unless their curiosity is sparked.

Okay. “…That I think you oughta listen to.” Kids will say, “Let me listen to the man.” I think the man lays down a decent game plan that has been misinterpreted. He lays a solution and he inspires and challenges the black man to use his brain and understand what has happened before. Which brings up the point of, “Listen, that was then, this is now.” Farrakhan says no. That phrase should never be used. Because you’re dealing with the after-effect. When I offer that line, that’s what goes off in kids’ heads. Or, “Supporter of Cheismard.” Twelve-year-old kid would not know about Joan Chesimard. But their curiosity is sparked.

When I came out with my first records, I had to be shocking in order to be heard. My job was just to tune the radicalness a little bit more. And to be shocking once again sparks the curiosity.

You make a lot of assumptions about black youth. You treat them as a singular idea, and as having one attitude, one mind, one situation.

Yeah. On the whole. Because on the whole everybody’s falling victim to the same obstacles. To be able to dissect and understand what’s happening to them or what’s happening to us, it takes years, or it takes constant teaching. And these things aren’t being taught in schools. They throw a bunch of facts about history, they throw you Kath and science, which are needed, and a bunch of things that are not needed in life. And the kids are not trained to challenge the information.

For example, the kid that says, “Listen, I just don’t agree with you” to the teacher, the teacher can’t deal with that most of the time, because they have to move the class on. They can’t go back. So a lot of black kids can’t challenge information.

And that’s where rap is filling a void, where before the parents used to talk to the child and say, “Listen, you watch this program, son, this is what it’s about, this is what he’s saying here,” and the kid is not getting his information just through what he’s watching or what he’s listening to or what he’s reading. He’s getting an interpretation from the parent who understands. Right now we’re in a situation where the parents don’t understand. Or if they do understand, they don’t know how to break it down for their son or daughter, because they don’t know how to communicate on a regular basis. Or in most cases, it’s not a father around, it’s a mother around, and she’s young herself, she ain’t got nothing in herded, or she ain’t got time.

I happened to fall into a situation that allowed me to have a thorough education because if something came across and my mother said, “this is what it’s about,” my father would say, “I don’t think so.” Even if they got into an argument, this would be interesting to me. My mother was a social activist in the Sixties. I guess whatever movement went down, she would support it: Angela Davis-type shit.

My mother was very strong. She always gave me that sense of radicalism from day one. And this weekend happens to be my mother and father’s birthday. I’m planning a big shindig. It’s probably going to be the happiest day of my life, to throw a party for my father.

What was the Afro-American Experience?

Afro-American Experience was a supplementary educational program for the black youth of Nassau County, Suffolk County, and Queens, run by the Panther leaders.

Which ones?

I can’t tell you who exactly. I remember Brother Lee. It wasn’t any big leaders. ‘Cause the Panthers had headquarters in every black community back then. The Nation of Islam had temples in most of the communities. The Black Panther Party was viewed as a positive organization for the betterment of black people and their communities, to get what they wasn’t getting. And they joined together with college students to create this program.

How old were you when you were in this program?

When I went I was 11. Don’t print my age. I was 11 in 1971. Don’t print my age.

Why not? What’s the big deal?

The big deal is that in order to communicate to the youth you have to be recognized as a peer. Something has to be there that they can say, “This is me.” So I’d rather not have my age printed. But at the same time I was eleven years old in 1971. My parents sent me, and I was reluctant at first, ’cause I felt I shouldn’t have to go to no summer school. I did well.

The program consisted of eight hours, Monday to Friday, education. I think it had maybe 1,500 kids. Hank Shocklee [Public Enemy’s producer] was there. We dealt with classrooms. I’m not saying disciplinary actions are right, but a couple times kids got out of line, and how a lot of the brothers would discipline the kid, everybody else would have to punish this person. Not by beating him up or spanking, but everybody would talk to him at once and tell him how fucked up he was for acting the way he did.

Were you ever punished?

No, no.

How did you like administering punishment?

I felt good, because I was convinced that it was for the betterment of all of us. Like a person broke a window on campus. Somebody was going to get yelled at, usually the brothers. First of all, they weren’t wanted on the campus. The communities forced the campus to allow this program to exist. So I felt pretty good.

You said in the NME that you went to the SPIN party looking for me, that you wanted to fuck me up bad.

I sure did. You appear to be a nice guy. Did you used to have long hair? I just wanted to speak to you mainly that night. I heard you was hiding out.

Everybody’s entitled to their opinion, I guess. But it’s bad that you keep your opinion limited. Because the whole market of rap is basically unable to judge information. I know that most of the market doesn’t read the magazine, but some do.

Black kids and the black market right now, they’re unable to challenge information. Or they’re unable to weight logic. My challenge is to put A and B and say, “Damn, don’t you see B is fucked up, and that A would be a lot better for you?” They have to get this, ’cause they’re not getting it in the school systems.

But do you really think they’re getting it from you? The objections I raised were that a lot of your lyrics were sloganeering.

Yeah, they’re getting it from me. You got to understand, the black market is schizophrenic. A lot of things are said with words or body language or things meaning something else. It’s like, if you go up to somebody and he says, [sputtering] “nigger bugging,” he’s saying a lot of things besides nigger bugging. It’s felt.

And I could understand it. Some white person with a middle class background or little contact with black people won’t understand that shit at all. There’s a lot of people in Creedmore [psychiatric hospital] that people can’t understand. You have to find people that are able to communicate to those that are unable to communicate to the rest of the world. Rap is a true reflection of the streets. It’s what R&B once was: the slang that you invent through music or the slang that you can pick up on the streets and then present through music.

Motown was once that. Marvin Gaye comes out with “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” based on his interpretation of what his mother told him. It became slang in the street. It was a teaching process and it was a reflection at the same time. R&B doesn’t do that anymore. Rap does it. It’s able to open doors to the mind. Rap deals. It’s abrasive. It doesn’t hid shit. R&B hides shit. It’s Barry Manilow, it’s Frank Sinatra.

I hate to talk about communism as Western civilization knows it, or even communism as it’s known today, ’cause it’s not fair, it’s not people dealing with people. There’s still somebody at the top, manipulating people. But I think capitalism should be a mixture. I think people should be treated fair from day one. In this situation right here, in the United States of America—I don’t even want to get mad at the fact that it’s so unfair.

If you get mad, what do you get mad at? Where do you direct your anger?

I try to direct my anger on trying to do something constructive for my people that are at a disadvantage.

That’s what you do with it. But who do you get mad at?

Right now, it’s hard for me to say, because it goes by the moment. There’s a lot of people I could get mad at, but I understand people, so there’s no hatred. I just try to throw a monkey wrench in the motherfucker. It all goes back to people saying, “Chuck D, what kind of government system would you have here in America in 1988?” I say, “One that says black people shouldn’t have to pay taxes.” It’s compensation.

Matter of fact, it’s overcompensation that we need to be behind the eight ball from 1609 to 1865 and thereafter, 120 more bullshit years. Slaves were brought to this continent in 1609; 1865, 256 years later, the so-called black man was free, quote-unquote “free.” So that’s 256 years of free labor to build this country. And then the animosity and hatred that went with the package afterwards.

When I say black people shouldn’t have to pay taxes it’s because we haven’t been compensated. I think that’s fair. Do you think it’s fair?

No. No I don’t.

Ha ha. That’s one thing I think should happen. Black people shouldn’t have to pay taxes.

That’s a bullshit reform…

That’s a bullshit reform. Also, we should be compensated $250 billion or whatever it takes to get each black family on its feet. Not saying that it will help a whole lot, because there’s still no brains. The slum of black America is in the middle of black America. But it would help. I’m talking about that’s a solution, A-plan. That will never happen. So we’re talking fantasy. People say, “Well…” What do you think I am, fucking Albert Gore? If I could give you A to Z, I might as well run. But I can do it. Give me some time.

People always looking to catch me in fucking doubletalk and loopholes. They treat me like I’m Jesse Jackson. I’m not running. I’m just offering a little bit of a solution, or at least explaining why things are the way they are. Which are fucked up.

Are you paranoid?

No, I’m not paranoid. I know there’s other things for me to do in this music. If it has to come through other means, I could give up doing records.

Your last single, “Bring the Noise,” was basically about what other people are saying about you…

Oh yeah, that was about you. I was talking right about you…

And now your new single, “Don’t Believe the Hype,” is also about what people are saying about you…

“Don’t Believe the Hype” is about telling people, “Listen, just don’t believe the things that are told to you.” Go out and seek, challenge information. “The follower of Farrakhan/Don’t tell me that you understand/Until you hear the man/I bring the book of the new school rap game/Writers treat me like Coltrane, insane/Yes to them, but to me I’m a different kind/We’re brothers of the same mind, unblind.”

We both known what’s happening, but we’re treated like we’re bugging. That’s why I say I’m treated like Coltrane. ‘Cause when Coltrane took his stance in the mid-Sixties, a lot of writers came crashing down on him because of his radical stance. He started becoming more and more radical until the day he died, started speaking his mind. A lot of people thought he was losing it. Today they recognize the man as a genius. I’m not telling you I’m a Coltrane fan because I’m getting into Coltrane. You probably know more about him than I do.

You call yourselves Public Enemy, and build a strong identity on that, but then the minute you get a little piece of criticism, you fly of the handle. Don’t you think that makes it a little exciting?

It makes it exciting. It also makes it untrustworthy. Listen. The only one I’m furious at over the past year is Greg Tate. That motherfucker sold out. I’m pissed at him, man.

I think that’s because you can’t take criticism.

I can’t take motherfuckers calling me a motherfucker.

Aw, big deal, Chuck.

I ain’t got to feel bad. At the same time, was it an album review or a character review?

I also deal on “Louder Than a Bomb” with the FBI tapping my phone.

Have they really, or are you just guessing?

I’m guessing. Because it’s happened to most black leaders. It’s no secret. The FBI does get involved with somebody even a slight bit outspoken. So it would be ludicrous and naive to believe that they won’t do it today. So if they do it, so what? What I say comes through on records and in interview. It’s no secret at all what I say, ’cause I’m louder than a bomb. They can tap my phone. The FBI had King and X set up. “Party for Your Right to Fight” deals with COINTELPRO, FBI, CIA, assignations and destruction of the Black Panther Party, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam.

You don’t believe that X was killed by the Nation of Islam?

No. And if he was, it was a set-up, some snake that was paid.

Do you have any reason to believe this, or is it just something that’s convenient for you?

It’s something that’s convenient for me. But also, if you look at it, it’s a pattern. It’s a real good guess.

You used to come out in the beginning of your concerts and say that the Klan was outside, ready to shut you down. But there was no danger of this.

No. But at the same time, I was letting people be aware that these forces exist.

And you feel justified in manipulating the facts in order to make that point?

Uh huh.

That’s the mark of a politician, to manipulate the truth to get across an agenda.

To manipulate the truth? You tell me another way to tell the truth to black people if they don’t want to hear the truth straight out. I’m open to answers.

You’ve complained constantly, in interviews and on records, that you can’t get your records on black radio, because black radio perceives you as being “too black,” too aggressive, too loud. So you make louder records, and you get them on black radio. Does that mean that you’re wrong about black radio, or wrong about the records?

My whole point is that black radio has a responsibility to the black community. Its responsibility, if the black community and the black youth wants to hear 50 percent rap records in that community, it’s black radio’s responsibility to play 50 percent rap records. Now don’t get on the demographic tip of trying to reach 25 and over of demographic black females, who aren’t listening to radio at night anyway. My wife don’t listen to radio. She’s watching TV till she falls asleep.

But you listen to the radio. I listen to the radio. Anyone in a car listens to the radio.

No. Anyone that drives in a car listens to tape decks. See, we’re dealing with different sciences here. That’s what’s accelerated the rap album public: car tape decks. Ten years ago, you bought an album so you could take it home to your turntable to play. I know, because I was there—I went out and bought an album to play on the stereo system at home, that I couldn’t play loud.

Over the last ten years the advent of the car stereo, the tape player, and also the box, and the Walkman—now a kid says, “I can take my tape, and I boom that shit loud.” Motherfuckers going out now and getting big systems, and it’s music to play loud. It deals with loudness. It deals with noise. I can turn it all the way up, park myself in the car, and play the tape that I just bought. Which explains why people are buying every rap album.

This is not music that you can go home and kick up your feet and listen to. This is music that requires activity; or if you’re gonna cool out, you’re gonna be in something that can be active in a minute, like a car.

Like I wrote “Bring the Noise” driving along the ocean where I live. Matter of fact, I wrote my first album in a car. I had a track in the tape deck, and I’m writing it on the Long Island Expressway, I’m writing it on the seat.

What’s the function of noise in your music?

To agitate, make the jam noticeable. When I originally made it, I wanted some shit where, when a car passed my house, I know that’s my song. It grew into a political thing, but I’m telling you the basis. Do you really find that much noise in our music now? It was something that we just put a label on, and found that people believed the label. Now it serves as a uniform. We wear it sometimes, and sometimes we don’t. We try to set trends, so we don’t stay on things too long. Now you hear it everywhere.

Nobody wants to judge us on our music. Everybody wants to judge us on our character. Journalists only cover me because right now it’s exciting. It beats the hell out of covering Morrissey 30, 40, 50 times, talking about the state of rock ‘n’ roll, which isn’t exciting at all.

Why do you take the bait every time an interviewer offers it?

Taking the bait? I’m not actually taking the bait. Sometimes the bait is thrown at you and you can’t get out of the way. It’s easy to attack us.

It’s no problem at all. It’s a matter of throwing you guys a noose and letting you put your neck in it.

Uh huh. But at the same time, I don’t look at it as putting my head in a fucking noose, because it’s not really dying. The music they can’t stop.

I’m just saying, being that I’m the only one that’s making this shit kind of exciting for a little period of time, don’t take this shit so seriously that you get hurt. ‘Cause I got a job to do.

Alright, Chuck, I’m straight. We can wind this up.

C’mon, you can’t be straight, man. Let’s keep talking…