This article originally appeared in the November 1993 issue of SPIN. To commemorate the recent passing of Silver Jews and Purple Mountains songwriter David Berman, we’re republishing it here.

Sitting before a computer in the closet-size, pentangular room off his kitchen that serves as Drag City records’ headquarters, Dan Koretzki, in his even, self-effecting tone, says, “I’ll be the first to admit that luck has played a huge role in the Drag City story.” A better word than luck might be intuition; Koretzky was hip to such critical darlings as Pavement and Royal Trux long before they were critical darlings.

The phone in Koretzky’s small West Side Chicago walk-up is ringing off the wall, mostly people begging tickets to the imminent (and already sold-out) Drag City Invitational, a three-day showcase of Drag City bands at the Lounge Ax nightclub, or else media dismayed to learn that there would be no, repeat no, guest list of any sort for the mini-extravaganza.

Pavement, one of the label’s initial signees that has since moved on to the “bigs,” are due to play on the six-band bill, and the locals are revved. It’ll also be the Chicago debut of the Palace Brothers, a dark little old-time ensemble about whom a buzz is current, and, of course, Royal Trux, one of the best live acts in rock’n’roll, will be there. Meanwhile, various band members and girlfriends shuffle in and out, scamming meal or lodging money.

Also Read

Every Pavement Album, Ranked

The Drag City label, which began in 1990, is one of a dwindling number of pure independent labels whose very name—like Olympia, Washington’s K., Philadelphia’s Slitbreeze, Los Angeles’ In the Red and Sympathy for the Record Industry, New Jersey’s Crypt, and Seattle’s Estrus, among others—has come to connote a certain attitude, if not outright sound, in the same way that once-mini Sub Pop is still identified with “grunge.” If rock’n’roll is supposed to be maverick music (and it is), then these wholly independent labels are rock’s last free range, and they are vanishing rapidly.

Some are being gradually sucked into the major-label vacuum via distribution arrangements, becoming quasi-indies; dollar demands of real life or shifting interests overtakes the twentysomething mini magnates in other cases. Just a handful, like Koretzkiy’s role models Dischord and Touch and Go, persist, integrity intact, for years.

In a lot of ways Drag City is typical of the deep indies—tiny fan-based and cash-strapped operations concerned not with careers or profit but with preserving sonic flashes in the pan, whether you give a damn or not. The 26-year-old Koretzky and his partner, Dan Osborn, a 27-year-old computer graphics whiz, are Drag City. Koretzky, who is able to subsist as the label’s sole paid employee on what he approximates to be about $5 an hour (Osborn keeps a job at a video-editing house) will pitch a project to Osborn or vice versa; when the other agrees it’s a done deal.

Contracts are handshakes unless the band wants something on paper. A few months later, one or two thousand records will hit the stores. While all Drag City long-players are available on CD, the focus has been on vinyl, the seven-inch in particular.

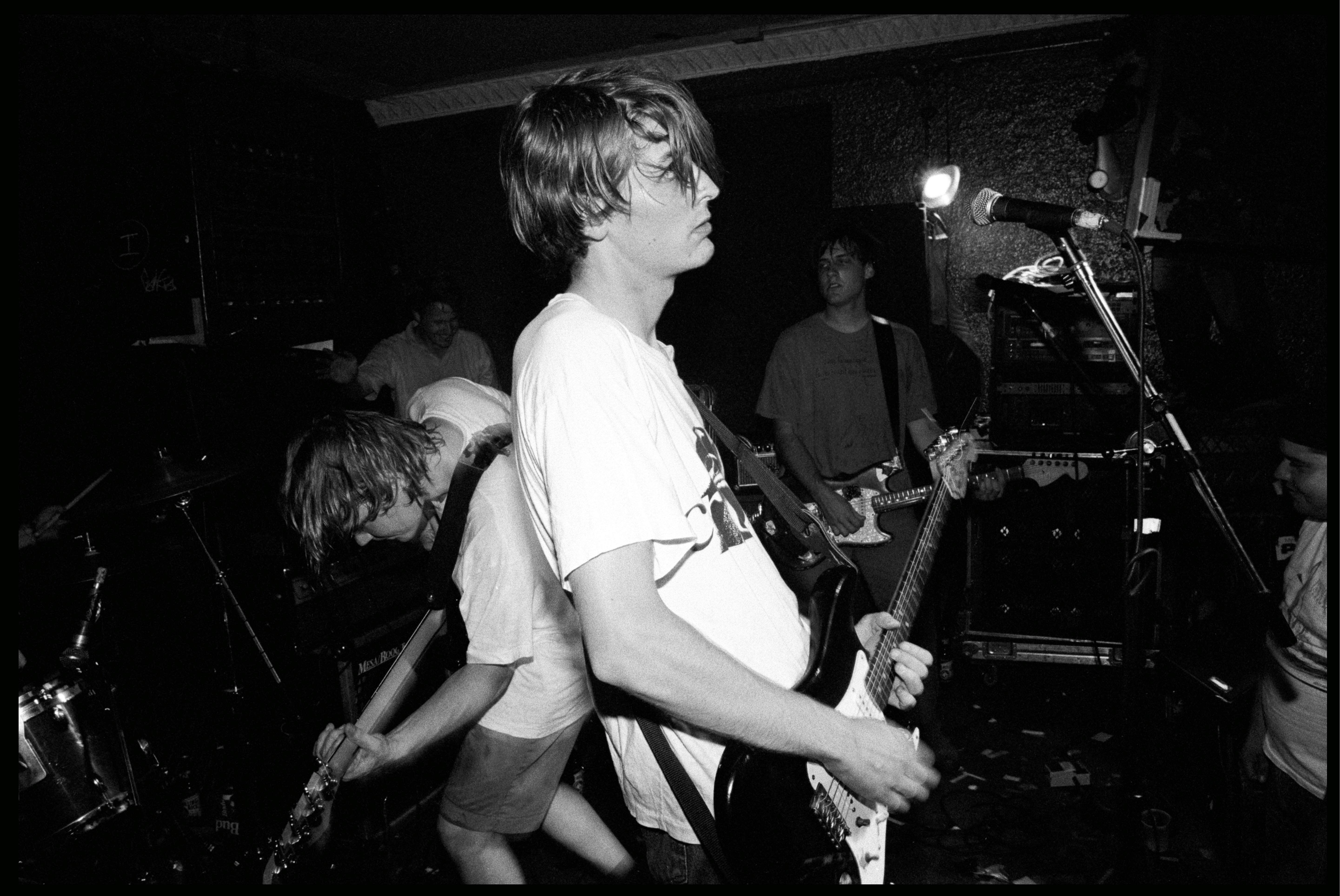

Unlike some of the aforementioned labels, there is no obvious Drag City “sound”; that much is clear through the cigarette fog and Lounge Ax as the first night of the Drag City Invitational unfolds. In an order allegedly drawn from a hat by a much-heckled MC (in fact, the first night was rigged), the bands appear one after the other, defying obvious linkage.

King Kong, from Louisville (as are the Palace Brothers), is a revelation in its show-opening role, stringing together its “Magic Sam—plays—Jonathan Richman” catalog in a gawkily choreographed mock rock’n’roll show that recalls the nascent B-52‘s.

Next, Bill “Smog” Callahan, a one-man recording operation whose obsessive four-track fiddling is compared more often to William S. Burrough’s disassembled word collages than any contemporary pop music, fleshes out his nervous, melancholic vibe with a drummer and an aggressively nerdish second guitarist (incidentally, “aggressively nerdish” would be the most apt description for the crowd’s fashion sense).

Drag City’s flagship band, Royal Trux, is next. A blurry plunge into a pool strewn with floating, rain bowing shards of Stones, the Band, and Little Feat licks, it is the label’s best live act. Buoyed by two flailing guitars, the gaunt Jennifer Herrema presides over the forestage in a solemn, unflinching manner, like a psychotic British bobby, staring at who-knows-what through a one-by-four-inch slot in a huge blond mane and daring anyone to get near her.

The mostly acoustic Palace Brothers play seated and backlit; they are fronted by Will Oldham, the adolescent preacher from John Sayles film Matewan, though you wouldn’t recognize him now. In contrast to the hill-hick aura of their Drag City recordings, they are apparently well-bred rich kids, but still sound remarkably like the 300-year-old first step in the evolution from English folk song to American country music.

Pavement is last, flipping their hair and preening and featuring a new drummer; the crowd, attentive and appreciative all night, pushes toward the stage, as they will each night.

Just what links the acts, beyond Koretzky and Osborn’s interest in them, is tough to finger. David Berman of the three-piece Silver Jews, whose band played the second and third nights, offers: “I know all the bands are obsessed with reading and literature. I told that to Dan the first time I came to Chicago—he was like, ‘Why doesn’t anyone like Drag City?’—This was early on—and I said there’s an intellectual streak in all your bands and American rock music is about glorifying stupidity for the most part.”

(In the program handed out each night, the Silver Jews’ page was a type-dense homage to the hyper-Goth author Cormac McCarthy.)

That Koretzky’s apartment contains—at least by weight—as many books as records (Thomas Merton, Don DeLillo, Philip K. Dick, Mad anthologies) may provide the key, but there is undeniably a Drag City vibe, and that vide is ultimately Koretzky and Osborn’s: despite the checkered flag on its logo and the like-titled Jan and Dean LP whose sleeve graces Koretzky’s living room, the “drag” in Drag City is more aptly synonymous with “bummed.”

“I guess most of the people aren’t too happy,” Koretzky chuckles at the suggestion. “But have you heard King Kong?”

Koretzky and Osborn’s label is probably best known as the onetime home of Pavement, whose Westing (By Musket and Sextant) compilation of pre-Matador singles and EPs is far and away Drag City’s best-seller at around 30,000 copies. Koretzky, however, would rather Drag City be remembered not as Pavement’s springboard but as chronicler of the exploits of the shape-shifting duo known as Royal Trux.

A “couple” dating back to their days on the periphery of the mid-’80s Washington, D.C., scene that Dischord chronicled, Neil Hagerty, the son of an Army intelligence officer, and Jennifer Herrema, the daughter of a real-estate mogul who’s seen precipitous ups and downs, moved to New York after Herrema convinced her parents to send her to the New School for Social Research. Hagerty tagged along, assured of a gig of sorts with Pussy Galore, the ratpunk band he’d been jamming with in D.C. that was making a concurrent pilgrimage to the Apple. Once there, the pair discovered heroin and began a self-induced plummet into oblivion.

Meanwhile, from his desk job at a Chicago record distributor, Koretzky wrote to Royal Trux after hearing the duo’s self-produced debut album. He offered to put out a single. The Trux agreed; “Hero Zero” became DC1 and sold briskly. Once they got some money back, DC2, Pavement’s “Demolition Plot J-7” seven-inch was released and did nearly as well.

Koretzky and Osborn decided it was worth trying an LP project.

The resulting Twin Infinitives was immediately hailed as a classic “difficult” set, á la Captain Beefheart‘s Trout Mask Replica, but the Trux’s health, as well as their chance to earn a living at the only thing they knew (music), was suffering. Snorting heroin, Herrema etched ulcers into her nasal passage that would not heal and she overdosed twice; meanwhile, the band’s reputation as megajunkies preceded it to towns and threatened to cost it gigs.

Hagerty and Herrema finally decided to detox simultaneously—it was her fourth stab at it and his second—and they’ve been clean—lucid, even—upwards of a year, rendering in that time two brilliant albums that sound just as thickly sickly as the first pair.

To keep the band vital Royal Trux is forever shifting its sidemen and its home base—from New York to San Francisco to D.C to…nowhere in particular at present, though Koretzky’s apartment is always a good place to check.

“They never sit still,” Koretzky says of Trux, who in an odd set-up for an indie, are planning to go on salary with Drag City. “They’re different from night to night, dramatically different from tour to tour. Even if something’s good they’ll trash it and do something different. I think a lot of what they’ve done is just trusting their instincts.”

Like those birds that clean crocodiles’ teeth, Royal Trux’s relationship with straight-laced Koretzky would seem to be one of nature’s odd symbiotic arrangements, one in this case based on a mutual respect for the other’s intuition. Besides crashing frequently in Koretzky’s apartment and raiding his library before tours, Hagerty and Herrema would seem as strong in their alliance to Drag City as the label is to them.

“The odd thing that’s cool,” says Herrema, “is that Drag City doesn’t say, ‘This is what we are.’ It says kinda like, ‘I don’t know what the fuck we are. We aren’t anything.'”

“I don’t think Koretzky’s conscious of what should be on the label,” Hagerty opines. “He’s like, ‘Somebody please give me something good.'”

For his part, Koretzky thinks Royal Trux is “doing the impossible…” He tosses his hands out and shrugs, “But then, I’m a diehard fan.”

Fandom is surely the cruz of Drag City. Of the six bands on the active roster, only one, the Palace Brothers, sent the label a demo. The others were all contacted by Koretzky the Fan. Bill Callahan had sold self-produced tapes out of a self-produced fanzine, Disaster, that Koretzky admired. King Kong had done two singles and an LP for other labels that he enjoyed. David Berman was introduced to Koretzky by Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich of Pavement, chums of Berman’s from their days at the University of Virginia and, later, New York City, where Berman and Malkmus worked as guards at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

By Saturday night it seems everyone is a little wilted around the edges. Same club, same bill, three nights in a row—after all, regardless of any pretensions to the contrary, these are not house bands; it’s art rock and this is seemingly a little like work.

Typically, only the Trux is better the third night—or as Herrema insists, “not better, different“—having earlier that afternoon switched guitarist and avid Noam Chomsky reader Mike Kaiser (an old-timer in the band with some nine months under his belt) to bass, and moving keyboardist Mike Fellows to drums for a good chunk of the set, allowing Herrma to rasp a little more sedately.

The Silver Jews draw the final slot, and in contrast to the murked-out, hand-held cassette-recorder quality of their two Drag City records, theirs is a nice set of crinkled and shredded garage, pop, a fine way to close the weekend. An impromptu “superstar” jam is attempted, but it quickly fizzles. Oldham approaches a mike, stage right, but is frozen into a pillar of salt. Only Hagerty seems to have any spunk left. The lights go up.

Finally, a visibly relieved Koretzky unenthusiastically rounds up all participants for a Drag City team photo. “Next year,” mutters Koretzky, in un-indie-like fashion, “I’m going to get some corporate sponsorship and hold this out in a park for free.”