This article originally appeared in the October 1999 issue of SPIN. In honor the 20th anniversary of the event, the 50th anniversary the original Woodstock festival, and the cancellation of the Woodstock 50 celebration, we’re republishing it here.

Friday: July 23, 1999

Liz Pruitt arrived at the third coming of Woodstock by bus. The recent high-school grad was hot and tired after a five-hour ride that began before dawn in a New Haven, Connecticut, parking lot and ended at a defunct Air Force base in upstate New York, but she was with three friends, and she was excited to be on site by 10:30 Friday morning. The dark-haired, willowy 18-year-old would have time to pitch her $30 Wal-Mart tent and walk more than a mile to the main stage before the first act played a note.

Her bus had “express entry” into the compound, so she wouldn’t have to wait in the idling line of autos that stretched down into the streets of the rusty burg called Rome. It dumped her by the gates, and she waited 20 minutes to have her bags searched and exchanged her $150 ticket for a wristband, and then she was inside.

It became clear right away, though, that no matter how much fun she was going to have during the next 72 hours, the ride might get a little bumpier. The $100 Woodstock travel package that had lured her from Norwich, Connecticut, included “preferred camping”—if she could find it.

“It became apparent that the staff from the bus didn’t know where anything was,” she says. “They said, ‘Just look for the yellow flags.'” Pruitt and her friends wandered aimlessly, before chancing on the flags and plopping down under some trees, becoming the four newest residents of an instant city of 225,000.

“I was kind of disgusted with the staff, but it wasn’t their fault. It was the fault of the people who hired them. They hadn’t informed them.”

The lines snaking outward from the entry gates at the former Griffiss Air Force Base that Friday morning were so deep and vast that they resembled nothing so much as a supplicant stream of refugees—albeit refugees who paid $150 to rock, and who were about to be charge $12 a pizza and $5 a beer. The gates and the surrounding three-mile-long plywood fence at Griffiss were bracketed by a phalanx of security guards who wore loud yellow T-shirts with the words Peace Patrol on them.

Inside the base, the sun, the concrete and the ever-expanding mass of human bodies jostled in perpetual competition for concertgoers’ attention. Woodstock ’99 was held in a triangular-shaped section of the former airbase, the surface of which was mostly concrete.

Two paved ex-runway tarmacs met on the north end of the site at a point that abutted the main gate. During the daytime the concrete became superheated by the blazing sun, an unavoidable feature of the hottest July New York had ever seen. Unlike the verdant, shady rusticity of Saugerties, New York—the site of Woodstock ’94—Griffiss offered no relief. Any spaces not taken up by vending booths, trucks, beer gardens, political-action tents, ATMs, and Port-a-Sans were deemed campsites.

As tens of thousands of people streamed in, it became increasingly difficult to stay oriented. A look in any direction across the flat landscape was blocked by the 10,000 sweaty faces closest to the viewer. The only usable landmark inside the base was the 50-foot control tower. Even the five-story-high East and West Stages, located one mile apart, weren’t visible from the campgrounds. The space set aside for the crowd in front of the East Stage alone was the length of three football fields. Above it droned a squadron of helicopters and an ever-present plane trailing a streamer that read, “Woodstock ’99—CD and Video Available This Fall!”

The festival officially began at noon Friday. On the East Stage, Tibetan monks chanted, and then MC Brother Wease yelled, “Show us your titties!” James Brown requested 30 seconds of silence for JFK, Jr. He got ten. Then he played “Sex Machine” and “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World,” two 30-year-old songs that would prove to be up-to-the-minute timely.

By 1 P.M., hundreds of people began to strip down in the oppressive heat. Public displays of affection quickly gave way to public displays of copulation. “Nudity was all over the place, and so was public fornication,” says 18-year-old Gary Rushnick. “But you really got used to it.”

At least 100 kids dove into a shallow mud puddle near the row of Port-a-Sans closest to the East Stage, largely unaware that they were slathering themselves in human waste. Men who encountered backed-up stalls relieved themselves in public, in what they took to calling “the piss pool.” Meanwhile, the Mud People, who quickly tired of hugging passersby, picked up chunks of mud and violently hurled them at the people drinking expensive warm lager in the adjoining beer garden.

Wearing an elaborate white feathered headdress, Jamiroquai‘s Jay Kay took the East Stage at 3 P.M. He was the first performer to tell the crowd to throw shit. They did. At him. Word got out that teenage sanitation workers, frustrated that the area was rapidly becoming one huge compost heap, were quitting. They said they had been given no instructions—and no water.

As the day wore on and the heat intensified, garbage cans overflowed. Paper, plastic, and pizza remnants smothered the wood mulch that smothered the concrete and dirt. Clifton Property Services, the sanitation firm hired by Woodstock, would later complain that the festival organizers hampered cleanup efforts. Woodstock failed to provide adequate plumbing for the vendors, so they had to build their own.

Vendors were also at the mercy of Ogden Corporation, the firm that partially owns Metropolitan Entertainment (which is co-owned by promoter John Scher) and set the prices for soda and water. According to vendor Frank Cristiano, water sold by Ogden to the subcontracted vendors cost a whopping $70 a case, more than $3 a bottle. Fans paid $4. Attendees who didn’t want to pay for bottles could drink from the free water spigots, most of which were located vast distances from the stages.

At the Action Lounge—an extreme-sports arena situated between the East and West Stages—attendees were charged $15 to skateboard, mountain bike, or in-line skate on, yes, a flat slab of concrete. A planned half-pipe had not yet arrived. The main attraction was a 10,000-square-foot “Shag-a-Quarium,” which included extreme-sports heroes, ESPN announcers, 20 cheerleaders, and a disco.

To compete with the crowd-pleasing flesh on display outside, nude competitions—rock climbing, BMX racing, wet-T-shirt contests, bridge—were hastily organized. “We were cautious to make it more comical and less sexual,” said Action Lounge manager David Pelletier, “but people were getting naked anyway. We just gave them a forum.”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”336553″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2019/07/GettyImages-2225813-1564358701-300×200.jpg”]

A few weeks before Woodstock, promoters John Scher, Michael Lang, and Ossie Kilkenny, three longtime concert promoters were found in violation of a 1970 law that was passed in the wake of the chaos of the first Woodstock. The promoters averted $1.5 million in fines levied by Oneida County for failing to meet deadlines the law set for transportation and security; they convinced the county to wave them, promising a staff of approximately 1,200 guards. Locals hired directly by Woodstock were promised $12 an hour, and subcontracted guards from around New York State earned $6 to $8 an hour.

Starved for bodies, the promoters hired a number of workers from guards who were told they’d work 12- to 14-hour shifts and get two meals a day. They were housed in on-site barracks with only cold water and slept on air mattresses. Some guards charged that other guards were looting each others’ quarters. “There was a lot of robbing in the Peace Patrol houses,” said guard Charles Knapp. “We chipped in to have our own security person.”

By Thursday night, a hundred guards had already quit. Friday, the undersized force was primarily deployed outside the gate; it mostly seemed concerned with getting concertgoers inside the base without drugs, alcohol, weapons, and important contraband like sandwiches and bottled water—stuff Ogden could sell. The searches were random, quick, often ineffectual, and stopped altogether once people had set foot on the base.

But people caught with drugs on their way in were often offered alternatives by some security guards. “They’d say, ‘Okay, you can bring it in for …,'” said Art Reid, a security supervisor. “They could make more money that way.”

“If the [kids] had mushrooms,” said guard Dawn Jones, “they’d let them keep ’em if they paid $20.” Body-searches were common, especially for women. “Girls who had been body-searched were complaining [about harassment],” said Jones. “They were visibly upset.”

Only one drug arrest had been made on Friday, and that was off-base: Nineteen-year-old Brooke Young was caught by DEA agents with a staggering 11,000 tabs of LSD. Young had tried to sell 6,000 hits to an undercover agent and had planned to sell his remaining 5,000 at Woodstock. He thought he’d make about $55,000 and probably could have if he’d gotten through the gate.

According to staffers, the Peace Patrol had been instructed by promoters to ignore everything but on-site physical violence. “They said in orientation that there will be nudity and drugs, and you’re going to turn your heads,” said a security guard named Mark, who did not want his last name used. “Turn your head unless somebody is hurting somebody else. You’re in a different world, no holds barred.’ That’s what led up to Sunday.”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”336579″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2019/07/GettyImages-51066406-1564360774-300×127.jpg”]

The MTV crew had been setting up since the day before in the media tower to the right of the East Stage and the control tower in the middle, where the sound engineer operated.

As MTV producers scoured the grounds for materials, VJ Carson Daly mostly hung with the kids to get their thoughts. They were happy to share with him. “You’re a fag!” yelled one. “I could fuck Jennifer Love Hewitt better than you could!” heckled another. One sated MTV viewer threw a cup of water in Daly’s face, and the beleaguered VJ mumbled, “Just tell me, man, that that wasn’t your piss.”

The mob of dirty, thirsty teens yelled, “Let’s get him!” and Daly and his crew fled. Pursuing garbage traced lovely parabolic arcs through the air but failed to hit its mark.

As evening fell, the medics in the first-aid tent behind the stage had treated hundreds of cases of heat exhaustion, dehydration, and bad trips—nothing too serious. It wasn’t till the Offspring took the stage at 7:30 that the crowd truly responded with abandon, and the first sprawling, brawling mosh pits took amorphous shape. Dexter Holland whacked the Backstreet Boys in effigy with a baseball bat.

Nineteen-year-old Justin Brake relished every minute of it, despite jamming up his own shoulder while slam dancing. “It was more than I bargained for,” he said enthusiastically, “an experience I’ll never forget.”

Since most of the 200,000 on base were by now firmly settled at the East Stage, waiting for Korn to start, anyone looking to take a breather could retreat to the campsites, which were quiet and empty, if rank. There was a definite sense of camaraderie. “Everyone was so friendly,” says Renee Carter of Fultonville, New York, “that we didn’t even worry about padlocking our tent.”

The sun had set, cooling the concrete tarmac. Airborne debris, seemingly equipped with Daly-homing devices, found its way onto the lofty perches of the MTV tower.

For all the shit-slinging, drug-taking, VJ-abusing, and spontaneous garbage-hurling, the real action didn’t get under way until Korn strode onstage at nine. The center-stage mosh pit raged with a concentrated ferocity.

Britt Abbey, who was watching from his post at his vending tent adjacent to the stage, saw five boys emerge from the mosh pit with blood-soaked T-shirts. “The crowd was hectic,” said Abby, “but it wasn’t too bad at all.”

Chaos erupted immediately in the backstage med tent. “When Korn came on, people were coming in every three minutes on stretchers,” said Rachael Hoke, a medical volunteer. The medics had prepped for the expected bruises, lacerations, broken bones—but Hoke was stunned by what she saw.

“Every single person in our tent was OD’ing. A lot weren’t conscious. One girl freaked out and broke the cot she was on. Seven EMTs tried to hold her down. She broke the restraints—they ended up having to duct-tape her to a backboard.” The EMTs loaded her into an ambulance. “She tried to bite the EMTs,” said Hoke incredulously.

Dave Schneider, who was volunteering at Woodstock’s Crisis Intervention Unit, watched Korn from the edge of the main pit. By now it was around 9:30, and the moshing was even harder than before. Suddenly, Schneider saw a crowd-surfing woman get swallowed up by the pit; when she re-emerged, two men had clamped her arms to her sides.

“She was giving a struggle,” said Schneider. “Her clothes were physically and forcibly being removed.” Yet no one nearby seemed to react. Schneider said that the woman and one of the men fell to the ground for about 20 seconds; then, he said, she was passed to his friend, who raped her, standing, from behind. “The gentlemen’s pants were down, her pants were down, and you could see that there was clearly sexual activity,” he said. Finally, the woman was pulled from the pit by some audience members, who handed her to security.

Schneider said he watched in horror as five more women were pushed into the very same pit throughout Korn’s set. “They were holding [the women] down and violating them. Maybe not everyone was raped, but the first one was, I’m sure.” The pit broke up before Schneider left for this 11 P.M. shift at the on-site ER, but since all the women had made it to the arms of security, he assumed the crimes had been reported.

At the ER, Schneider watched as a 15-year-old girl who had OD’d on an estimated ten hits of Ecstasy was brought in unconscious. She was unconscious the next day, when he left. The only death of the day, officials said, was a 44-year-old Woodstock ’69 veteran who had had heart surgery 11 days earlier. He succumbed to the heat.

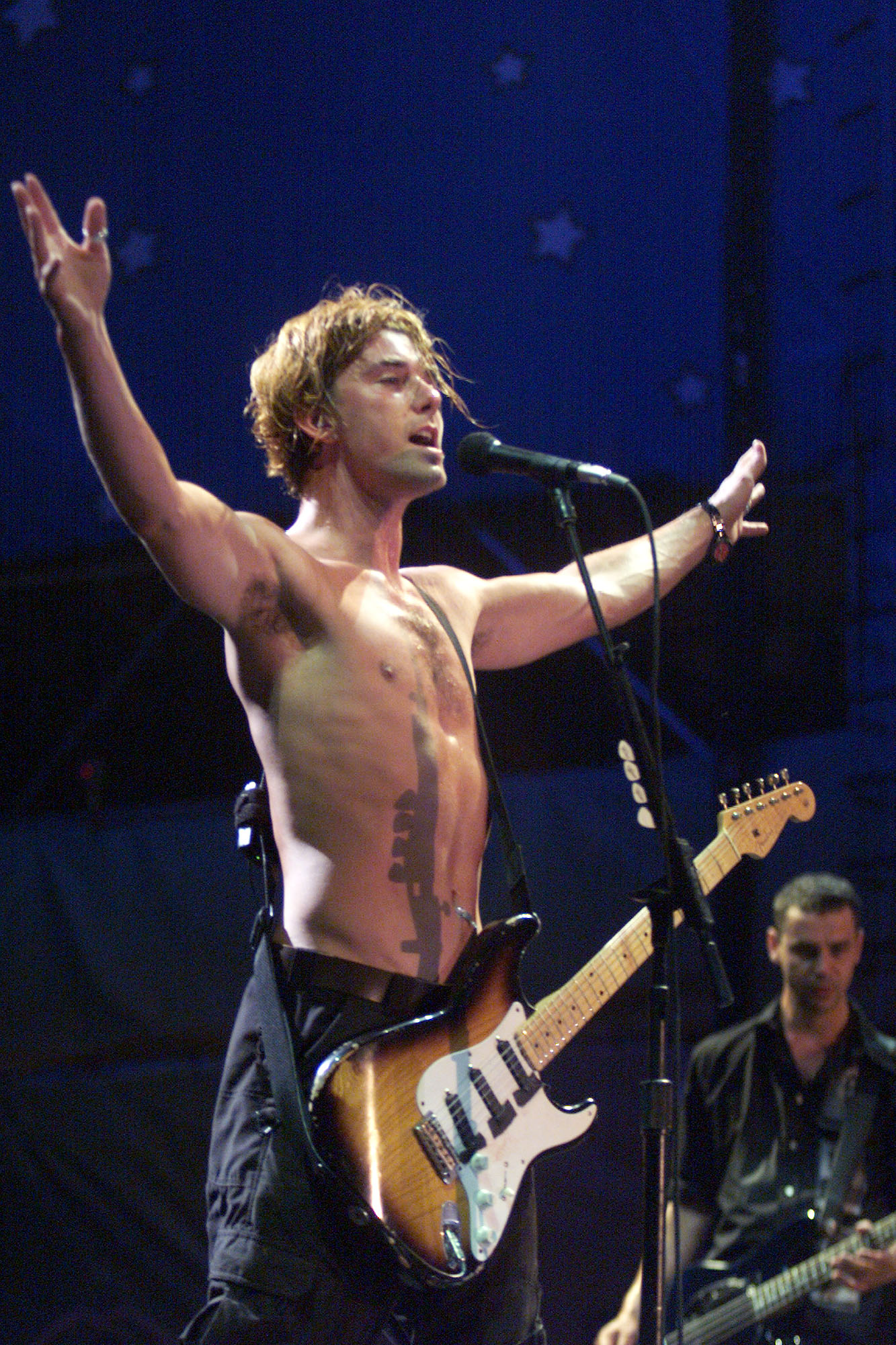

The girls took over two hours later, at 10:30, when they pushed their way to the front for Bush. By now, a tacit rule had been established: If you were a girl, and you were topless, you were going to get groped. If you were a girl, and you weren’t topless, you were going to get yelled at for not being topless.

“There were naked women all over,” said Pruitt. “I got so sick of it. I was like, ‘Put those away!'” Bush singer Gavin Rossdale gazed out at the sea of half-naked woman and said, “This is the best thing I’ve ever seen.”

Around 2 A.M., at the Rave Hangar, 25,000 people seemed determined to outperform the day’s communal hedonism. They pulled it off, ingesting a staggering amount of drugs and engaging in a staggering amount of public and/or group sex as first Liquid Todd, then Moby, provided the soundtrack.

“There were a bunch of naked dues, and girls were just taking turns riding them,” said rave promoter Matt E. Silver. “There were girls having oral sex with each other in the DJ booth. We had a topless girl dancing, and people were pouring orange juice on her and she was licking her titties. We were calling it Titty-Stock.” A 30-year-old man tried to pick up the fully clothed Pruitt, to no avail.

There was a large contingent of security at this event. But most had removed their badges, stripped off their T-shirts, and started partying like regular unlawful Americans. They were oblivious to the observant kids who quickly seized upon their discarded laminates and made their way backstage. “In the dance area, where there were no rock bands, the vibe was terrific,” said Moby. “Unfortunately, I didn’t get laid.”

Saturday: July 24, 1999

On Saturday morning, Joel Ferree was waiting outside a Rome bowling alley. Yellow school busses were ferrying latecomers to the former Air Force base, because full parking lots prevented anyone from driving anywhere near the site.

The bus rolled up, and Ferree took a seat. He was met with a musky combination of body odor and pot smoke. The passengers were shouting “Metallica!” while they banged their heads to a boom box blasting “Enter Sandman.” Someone suggested that the bus driver indulge in a bit of smoke, and everyone agreed that this was a truly fine idea. They tugged on her arms until she turned and yelled, “Get off me, you cocksuckers! I’m driving.”

Soon the bus passed a barricade lined with police officers, and a quick-thinking passenger yanked his shorts down and pressed his ass against the glass. The bus occupants cheered.

At the morning’s press briefing, Woodstock co-promoter Scher was detailing his priorities for the festival. “You can have a Woodstock, and it can be a safe and secure environment,” he said. “We’re going to try and make a profit on this one.”

That morning the sewage conditions at Griffiss were even worse than the day before. Port-a-Sans were clogged up and overflowing, and waste streamed into the field; several campsites were suddenly a wash in rivers of human waste. A few campers, seeking relief from the sweltering temperatures, had unscrewed the nozzles from nearby water spigots to keep the flow constant—which meant: 1) a lot of those water sources had dried up; and 2) some of the water that was still running had been contaminated with E. coli bacteria, which was flourishing in the omnipresent “mud.”

Now in addition to the kids who were dropping from heat exhaustion and dehydration, there were just as many who were uncontrollably vomiting or doubled over with stomach cramps. These ailing concert goers were faced with three options: use a feces-splattered Port-a-San, which would likely make them sicker; run for it in hopes they made it to a medical tent in time; or squat down in the dirt and add to the overall squalidness. Many chose the latter.

At noon, the Canadian band Tragically Hip played the first set of the day on the East Stage. The Canadians were representing. There were faces painted with maple leafs and Canadian flags worn like superhero capes. They began singing “Oh Canada.” At which point patriotic American audience members drowned them out with their version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” while pelting the Canadians with rocks and bottles.

Also at noon, the beer gardens opened for business. Surrounded by tall wire fencing and elevated stations from which security could monitor the perimeter, and devoid of anywhere to sit, what the promoters called gardens were more akin to prison yards. The one near the East Stage had been packed to capacity the day before, but this afternoon it was mostly empty. The beer-drinking crowd had already migrated to the East Stage in anticipation of Kid Rock‘s set, and patrons of the garden were only allowed to buy two drink tickets at a time without exiting and reentering the garden—so they weren’t sticking around for very long. In response, panicked workers abandoned the two-drink-maximum rule and handed out chunks of drink tickets—sometimes 20 or 30 at a time—to get things going.

One hour later, an enterprising local radio station, WEDG, put two naked women on top of its RV and used the loudspeaker to recruit willing females. Britt Abbey, who worked the vending tables closes to the right side of the East Stage, says packs of shirtless, sweaty guys clambered atop the tractor trailers behind him and yelled “Show us your tits!” at passing women. Their friends on the ground would block women’s paths, swarming around them like ants.

Some women would laugh and deliver the goods; others were unamused and picked up their pace. One woman charged men $20 (an Andrew Jackson, please; no charge) to watch as she inserted the rolled up bill in her vagina.

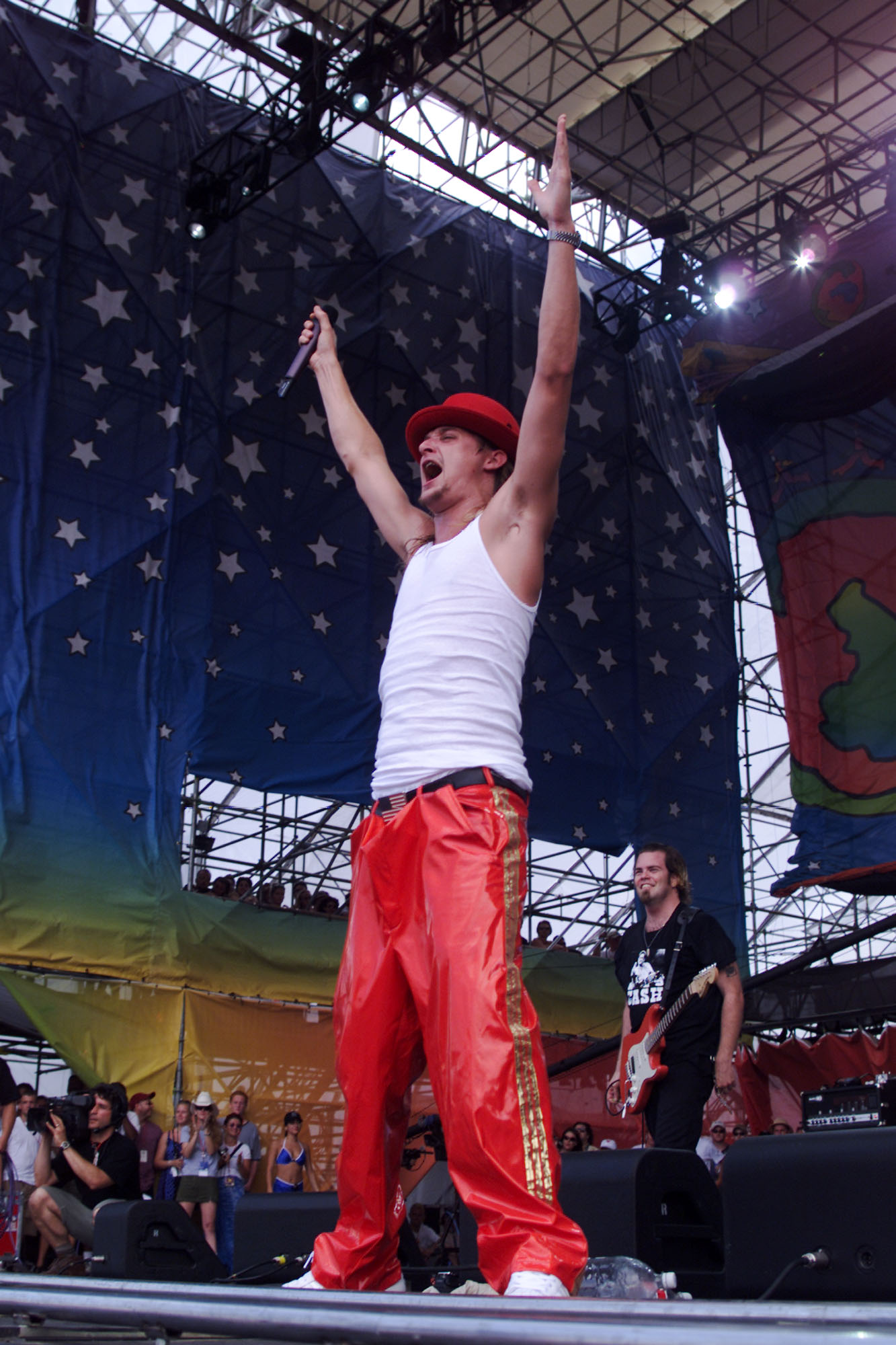

At a quarter past one on an 88-degree day, Kid Rock took the stage wearing a full-length white fur coat. He told the crowd to say “You want my balls in your mouth?” instead of fighting if they got in a confrontation with someone. A few songs in, Rock’s sidekick, Joe C., came out dressed in a hysterical Jimi Hendrix costume. Then he changed into a T-shirt that read “I’m Not a Fuckin’ Midget,” smoked a joint, and cursed himself sweaty. The crowd had unmitigated love for Kid Rock and showed it by throwing their bottles in the air like they just didn’t care. Some who forgot to duck got their scalps ripped open.

Around 3 P.M., Wyclef Jean performed a fairly embarrassing Hendrix imitation, in which he attempted to set his guitar on fire. He burned his hand. Dave Matthews took the stage just before 5 P.M. Far more girls than boys were up front. But this was Woodstock after all. Dave Schneider, who had witness the rape during Korn, saw a crowd-surfing girl’s clothes get ripped off during Matthews’ set. By the time she was passed off to security, the only piece of clothing to remain intact was the collar of her T-shirt.

Alanis Morissette arrived onstage a little before seven. She was hit by a lot of shoes. A woman (who asked that her name be withheld) said that although she had been assaulted while watching Tragically Hip earlier, she was sure that the pit for Morissette would be much safer. She surfed her way to the front of the stage.

“I don’t know how they got me,” she said. “There were about three guys on each arm and each leg, and then three or four right inside me with their hands. One guy put his hand inside my anus. Another guy was yelling, ‘Rip her apart!’ The woman finally managed to extricate herself from the pit by kicking some of her assailants in the head. She sat on the ground and cried. Some passersby tried to ask her what was wrong, but she couldn’t even talk. “All I wanted to do,” she said, “was kill somebody.”

In the 20 minutes between the end of Morissette’s set and the beginning of Limp Bizkit‘s, there was a sea change in the crowd. Boys pushed forward and prepared to mosh. Girls, for the most part, ran for their lives. By Saturday afternoon, kids without tickets had split open small gaps in the Peace Wall, the wooden fence that bordered Griffiss, and broken in to the grounds. Security was unable to keep up. One yellow shirt noticed a boy with pierced nipples and a mullet climbing over a still-standing ten-foot-high section of Peace Wall. It was painted with a portrait of Jimi Hendrix that made him look like an Ewok. The guard yelled at the boy to get down. “Fuck you,” said the boy. “Fine,” shrugged the security guard, and he walked away.

In all, only 175 security guards showed up for Saturday night’s shift. And that’s who signed in, not who actually stayed. The bosses made a call to prisons and jails looking for correction officers willing to work on short notice for supervisors’ pay. Forty materialized.

While the guards were disappearing, the crowds were growing. Another 25,000 fans had arrived late Friday night. With fewer guards on the gates, more contraband began to seep in, especially nitrous-oxide tanks and beer. Soon, a small fleet of entrepreneurs were selling nitrous-filled balloons from the tanks. A short time later, the med tents began to see people who were sick from inhaling too much nitrous.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”336583″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2019/07/GettyImages-104846363-1564361075-300×181.jpg”]

There were just minutes to go before Limp Bizkit took the stage, but the crowd was so worked up they began throwing stuff with an inventiveness and dedication not seen before. At this point, hurling shoes and mud was an amateur pursuit. People moved on to batteries, disposable cameras, and rocks the size of hockey pucks. The media tower to the right of the stage, the camera platforms to the left, and the control tower to the middle of the airfield were swarming with kids who peeled off each structure’s protective plywood like worn Band-Aids.

Someone found an uncracked watermelon and hurled it at the MTV tower, where crew and talent were now huddled, many with their heads in their hands to deflect flying detritus. The MTV crew canceled their plans to tape Limp Bizkit’s performance and dedicated to go live at 10 P.M. from the backstage first-aid area. “The MTV people were kind of shocked and overwhelmed,” said an MTV staffer. “I mean if you have 250,000 kids bent on destroying you, you’re gonna get rattled.”

At 7:45, hippie totem Wavy Gravy appeared on the East Stage and said, “Enough of the mellow shit.”

Not long after, Limp Bizkit singer Fred Durst yelled, “How many people have ever woke up in the morning and just decided you’re going to break some shit?” before tearing into—what else?—”Break Stuff.”

Many in the audience took the song literally: They broke arms, legs, teeth, noses, collarbones. Scalps were lacerated by flying, half-full bottles. One mosher suffered a compression fracture of the spine. Another broke two ribs and prodded the medic treating him to finish quickly so he could return to the pit. Yet another boy’s shoulder popped right out of its socket. As he stumbled toward security, his fellow moshers yelled, “Pussy!”

The first-aid tent, located behind the East Stage, was now seriously overflowing. EMT workers had trouble getting to kids who went down in the pit because the crowd wouldn’t part for them. An estimated 200 people per hour were treated in the two med tents near the stage; ambulances took about a dozen people to local hospitals for examination.

The MTV crew watched as the bodies piled up in the first-aid area, all the while dodging the rocks and bottles that the watchful crowd had retargeted at their hideout. Unfortunately, their aim was off, and they hit some kids who were, respectively, hooked up to IVs, vomiting blood, and OD’ing. “It looked like the M*A*S*H* triage unit,” said MTV producer Tim Healy. “The only people missing were Hawkeye and BJ.”

The EMTs were caught off guard by the level of casualties. “The busiest time for us,” said Dr. Phil Vuocolo, Woodstock’s medical director, “was Saturday night into early Sunday morning.” Drug-related cases—resulting from Ecstasy, mushrooms, LSD, Ruphinol—plagued the medical units as well. At one point, a weary medic walked over to Healy and said, “Dude, do me a favor. Just tell everyone you know to stay away from the liquid Ecstasy.”

Meanwhile, Durst was exhorting the crowd to “get all your negative energy out.” People soared through the air with as much frequency as garbage; a few were flung skyward on bed sheets. Between songs, Durst made an announcement: “They want to ask you to mellow out. They said too many people are getting hurt. Don’t let nobody get hurt, but I don’t think you should mellow out!”

Around this time, an overzealous spectator fell from a sound tower. Soon after, the band lost all sound, and Durst stormed off the stage. By some accounts, a sound engineer thought a grave injury had befallen the spectator and had cut the sound feed.

Less than three minutes later, sound was restored, and Limp Bizkit tore into “Nookie.” Durst tried to body-surf through the audience using only a sheet of fan-liberated plywood. The attempted failed, and security shepherded him back onstage. The band played their cover of “Faith,” and the crowd went nuts.

Women who were sitting atop their boyfriends shoulders were smothered by hands. Tops were torn away like tissue paper; girls fought valiantly to keep their pants on as boys tugged them down around their knees. Crisis-intervention workers who watched Limp Bizkit’s set saw numerous sexual assaults in the mosh pits; one woman later reported to police that she had been raped, then had surfed her way out. She said that the size and mood of the crowd stopped her from yelling for help—she was afraid she’d be beaten up.

Still, a lot of the younger girls never felt threatened, whether or not they were near mosh pits. “From where I was,” said Liz Pruitt, who stood near the front of the crowd, “it seemed like any other show, ’cause all I saw was people with their hands in the air. I felt safe.” There was little pity for those who were unprepared for what they found in the front rows. “If you didn’t want to be in a rough situation there, you shouldn’t have been in the mosh pit,” said reveler Dough Calahan. “I’m tired of people making excuses for their own fucking stupidity. Limp Bizkit equals mosh pit. Duh.”

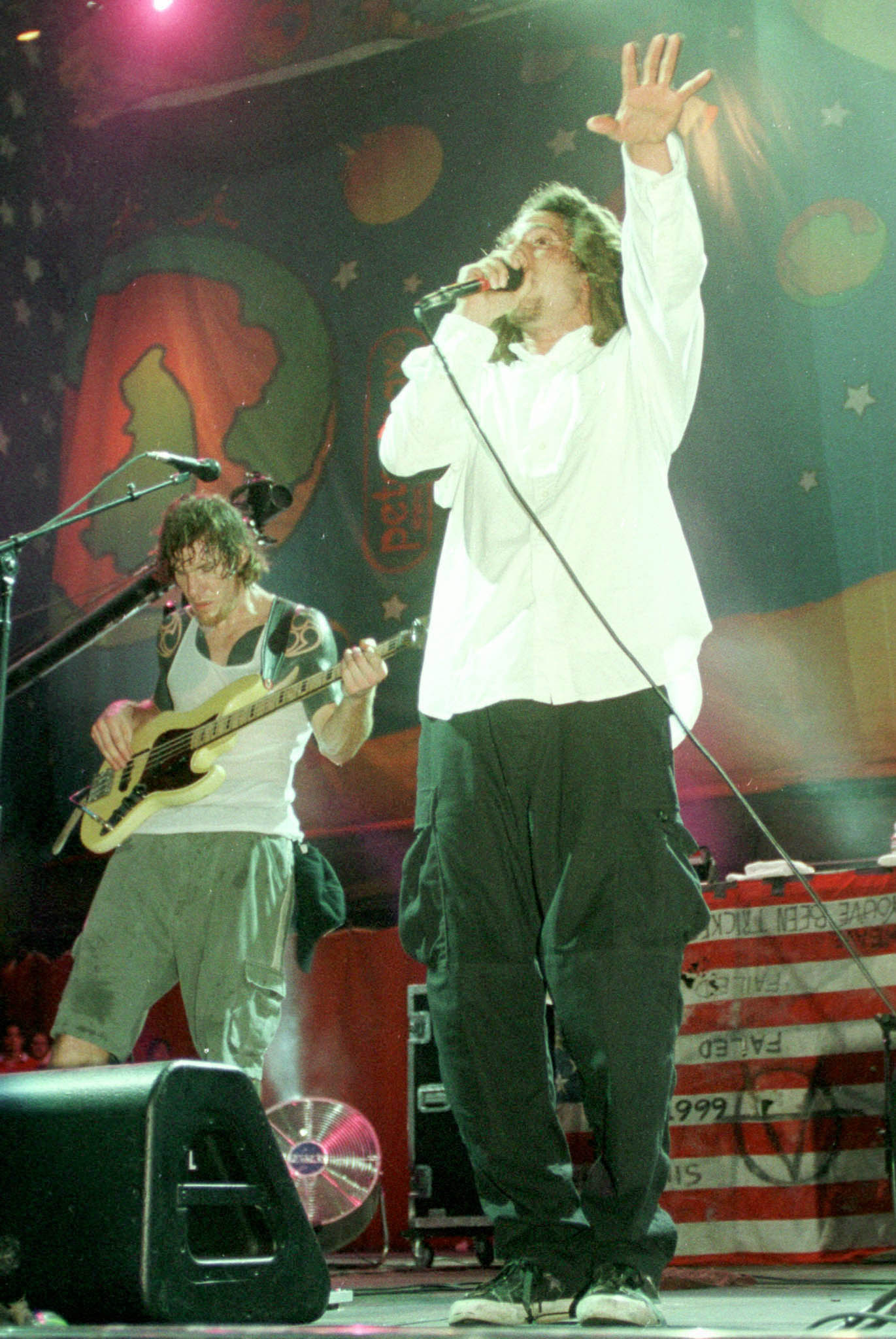

Forty-five minutes later, Rage Against the Machine started playing “No Shelter” from the Godzilla soundtrack, an appropriate song, all things considered. Behind the band was a large amp draped with an American flag. Bassist Tim Bob set it on fire when they exited the stage. Rage toned down their set in an attempt to keep the post-Bizkit crowd from actually transforming into a new species. Those in the mosh pit nonetheless got a workout. One man pulled off his shirt and set it on fire, then waved it around in a circle.

A 100-foot section of the west wall between gates two and three came down during the night, perhaps as early as 11 P.M. Security put out a number of small fires in the campground. There were a few minor attempts at looting.

Near the center of the compound, in the beer garden, about a hundred people were chanting “Fuck the police!” This coalition of oppressed music-loving beer drinkers was organizing to rush the two security guards who wouldn’t let them leave with their beers. Hundreds of people chanted in unison but nobody stormed the gate.

* * *

Rain threatened Saturday’s final performances. On the East Stage, the members of Metallica all wore black and didn’t say much to the crowd beyond, “Thank you, friends,” and, “You motherfuckers want some more?” They played furious speed-metal oldies like “Seek and Destroy” and a head-exploding version of “One.” But the rear-speaker delays were fried, and the crowd thinned appreciably. After the first encore, around 1 A.M., Kid Rock appeared and handed a salutatory Corona to drummer Lars Ulrich.

“We turned it up to about 11 that day,” said Ulrich later. “We’ve been through this shit for so long, we fuckin’ know how to deal with these situations—what to do and what not to do. If there’s that kind of energy in the air, you just go out, shut the fuck up, play your music, and get on with it. You don’t want to further ignite it.”

Halfway through Metallica’s set, at 12:36 A.M., 24-year-old computer analyst David DeRosia had walked into a first-aid tent complaining of heat exhaustion. His friend David Vadnais—who had last seen DeRosia at midnight, right before Metallica began—said that he seemed fine. But when he couldn’t find him later than night, he got worried. On Sunday afternoon he was told by medics that DeRosia had been evacuated by helicopter to nearby University Hospital.

On the West Stage, where the Chemical Brothers were spinning, the music paused momentarily while 150,000 frenzied dancers were informed of the impending storm and instructed to hit the ground if lightning struck. In response, everybody threw their hands in the air.

“It was our favorite gig of the whole tour,” said the Chemicals’ Ed Simons. “It was a cool vibe. It was more like what Woodstock was meant to be, as opposed to what was happening on the other stage.”

Wet and exhausted and not yet sated, tens of thousands of people, including Simons, strolled over to the Rave Hangar, where Fatboy Slim spun until 3:30 A.M. Ecstasy and acid were brazenly offered, sold, and dropped. As she walked through the maze of people, 23-year-old Lara Buthfer stumbled upon five girls having sex with one another. One woman won herself a free nitrous balloon by standing on the bending table shedding her thong, and lowering her booty to within inches of the stunned face of the guy selling the balloons. But still, this was Woodstock.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”336596″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2019/07/GettyImages-599363868-1564361888-300×200.jpg”]

Spencer Tunick, a photographer who specializes in large stills of naked people, saw a woman being violated as she sat on a man’s shoulders. “She must have been on some substance,” he said, “she was so passive. It was just unbelievable how many hands went up there. She was surrounded by 20 guys in khaki shorts.”

In the beginning of Fatboy’s set, someone who had been hired to install the half-pipe in the Action Lounge drove a 14-foot U-Haul truck, with five guys dancing on top, straight through a hangar in an attempt to get to the stage. Though the driver was promptly arrested, he politely backed the truck up before being taken into custody.

The unincarcerated joyriders then walked back into the Action Lounge and lit a fire in a garbage can, inspiring others to douse hay bales inside the Lounge with gasoline and set them ablaze. The fires were quickly doused.

“Another 45 or 50 seconds of this would have been very dangerous—I mean, extremely dangerous, causing loss of life and stuff,” said David Pelletier, the Action Lounge’s manager. “There’s rock’n’roll and skate culture, but when people start getting hurt in the spirit of fun, that’s not fun anymore.”

Sunday: July 25, 1999

Allison Mann woke up early on Sunday morning. As she was enjoying a Fluffer nutter sandwich, some kids from the Monkey Sex Cult came around.

The Monkey Sex Cult was a group of guys and girls—okay, mostly guys—who were trying to meet people—okay, mostly girls. “It has to do with a mating thing that monkeys do,” said Mann. “How monkeys scare each other before having sex. They came up to people and were, like, ‘Join the Monkey Sex Cult!’ and they’d say ‘uh huh’ and keep walking. But it was a lot better than saying, ‘Show your tits!’ like everyone else.” Other people must have thought so too. About 20 of them joined.

Around the Monkey Sex Cult compound, the campgrounds were wrecked. Garbage was strewn everywhere, collecting in fetid piles that began to resemble landscaping in some of the less desirable neighborhoods in Manila. The flooded Port-a-Sans clusters were seeping their content at an ever-faster rate. Small lakes of fecal matter slowly but relentlessly invaded several of the camping areas. Some of the shower facilities were either turned off or the water pressure was shot. Small groups of naked, dirty, and often bruised concertgoers stood around in a daze using pools of dirty water to exchange the dry filth on their bodies for new, wet filth from the puddles.

Earlier that day at a press conference, Scher admitted that the previous days’ events were “a frat party to a large degree.” Ken Donohue, the head of Metropolis Entertainment security, said, “I think the event has been a great success from a security point of view.” Co-promoter Michael Lang said, “We’ve lost 15 to 20 percent of the security force. Some were let go. Through shift changes, I think we’re having the right level of security.”

But actual security guards, like Mark, the guard who didn’t want his last name used, described it differently. “At this point, they were kissing our feet to get us to work.” Scrubs had been quickly promoted to supervisor as the ranks thinned. Units of 14 had shrunk down over the days to two or three.

At 9 A.M., the depleted security force repaired the 100-foot hole in the wall near the main gate, which had been gouged the night before. By 10:30 A.M., the wall started coming down again.

According to Art Reid, a security supervisor on the South Gate, “They had an incident sometime around noon where 200 security guards quit.” The head of supervision for the security guards held a quick meeting and said he placed another emergency call to the correctional facilities to try to get 200 correctional guards to replace them. No one came.

Ogden had run out of water on Saturday, and some local vendors who bought their own supples sold water for $2 and $3. They had wanted to drop prices anyway when it got hot, as had the medical staff. Ogden told them to keep the price at $4 or they’d close them down. Individual vendors who tried to reduce prices on sandwiches got shut down or were threatened with fines.

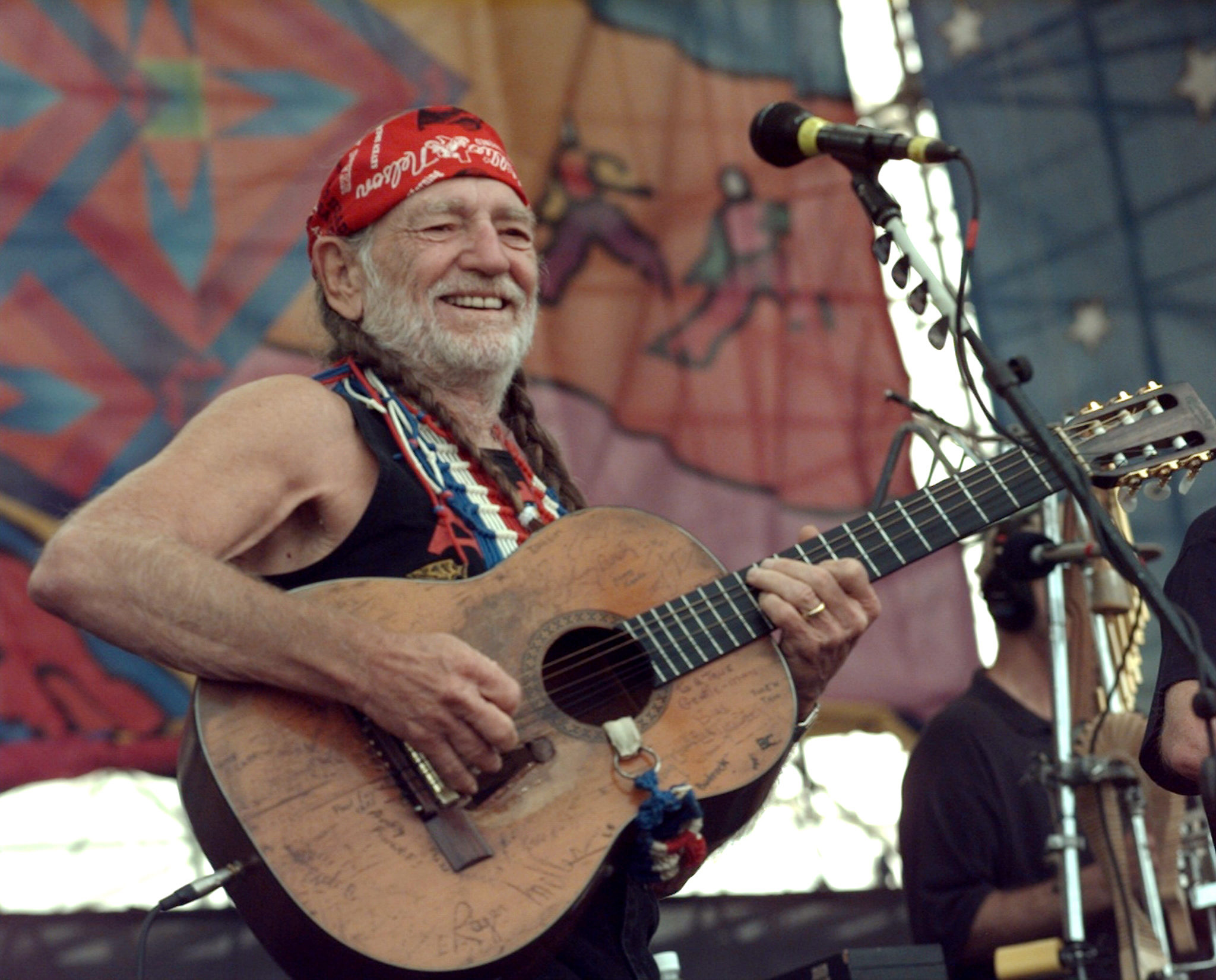

At 1 P.M., Willie Nelson was playing on the East Stage and Mike Ness on the other. Very little trash had been picked up for the duration of the festival, and the entire field before the East Stage was dotted with garbage. Fans picked through the refuse to find a clean pizza box upon which to sit. The crowd had thinned substantially from the day before, and there was a conspicuous absence of security. Pot clouds began to amass over Nelson’s audience.

By 2 P.M., Reid’s unit had to abandon the gate and watch as beer and other contraband poured in. Around the compound, security guards were taking off their shirts and melting into the crowd. Two tractor trailers full of bottled water, condoms, and gum fell prey to looters by the West Stage. The Robin Hoods sold the water for $2 a bottle.

A few hours later on the East Stage, Everlast covered Marvin Gaye‘s “Trouble Man” as a helicopter drew lazy circles above the base. The crowd was thicker by this point, and the usual stuff began to find itself airborne: bottles, trash, toilet paper. Many audience members were hot and pissed off. Some shoes were thrown. Everlast paused and addressed this. “Karma’s a bitch,” he said. “You better recognize that and act accordingly.”

After the concert, Everlast added, “People are trying to blame bands for what the kids did and say what a reflection it is on this generation. All those people are nostalgic for something that happened 30 years ago. I don’t think anything real came out of that first experience—it was just three days of sex and drugs and ‘Oh, the world is such a great place!’ Then they went home, became yuppies, and fucked the whole country up.”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”336599″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2019/07/GettyImages-51066431-1564362244-300×223.jpg”]

By mid-afternoon, rumors circulated among the security staff that they would be attacked if they didn’t take off their yellow shirts, and that the vendors would be next. “There was a weird aura on Sunday,” said Dave Bobela, 19, a student working in the vending tent closest to the West Stage. “People were getting cranky. The vendors were getting a lot of trash talked at us. If you weren’t cutting deals with customers, you were basically shit. I cut some deals, just to be nice. By then, I didn’t give a damn if the person I was working for made any money.”

Lots of kids were seriously blitzed, mostly on beer. Three days of being wasted in the broiling sun was beginning to have a profound neurological effect on the crowd. The camping areas were full of strange sounds: moaning, screaming, various expulsions of gas. Some attendees, exhausted or attempting to beat the post concert exodus, or both, packed to leave. But those who stayed appeared to be digging in.

Standing on the side of the path that led to the back of the tents was a 19-year-old brunette holding a bottle of Johnny Walker. “Free Scotch! Free Scotch!” she called out. As people drew from the bottle, a man who she had just met repeatedly lifted her shirt to lick her nipples. The boundaries and established social conventions that had been assaulted all weekend now seemed completely breached.

At the perimeter of Griffiss, the fence had also been breached—not by people trying to crash the concert but by the concertgoers themselves. Most wanted a piece as a souvenir. Others wanted fuel. Small blazes were starving across the base, initiated with symbolic-yet-conveniently-flammable chunks of plywood murals tossed into a heap and set afire. The first appeared to have been started at the rear of the campsite, near the West Stage.

About 30 people stood peacefully around a medium-size bonfire cheering the flames, drinking beer, and passing joints. A fire crew and state troopers appeared quickly, but they seemed to take the whole thing as a joke. They sprayed out the fire, then turned the hose in the air for the crowd. As kids realized that there was very little consequence for their actions, small fires burned through the late afternoon.

While more concertgoers discovered the joys of dismantling the Peace Wall, the police contemplated the proper response. A state trouper Chevrolet Tahoe cruised the access road next to the wall and pulled over. The crowd ignored it. One of the officers called out to the wall-dismantlers on his PA. “Hey, bring us a piece, would you?” A man brought the officers a choice fragment. The cop placed the plywood in his trunk. As the police drove away, one of the men stopped atomizing the Woodstock Peace Wall long enough to yell, “Thanks, man! You guys rule!”

* * *

Dressed in a black tank top and tight capri pants, Jewel took the stage around 5 P.M. A sign in the audience read “Jewel: Fuck Me Now.” Jewel was unfazed. Jewel yodeled. The audience was unfazed.

“The crowd was really weird,” she said a week later. “Generally when you do big shows like that it’s always a bit weird, but here people seemed real strung out. Real tired. But I was pleased ’cause people really seemed to listen.”

Soon after, it rained.

Although they were brief, the showers managed to cool down the entire arena for the rest of the evening, the temperature settling into the comparatively sub-arctic mid-80s. Concertgoers perked up almost immediately. People ran back and forth, jumping up and down, yelping unintelligibly. A group of boys took over one of the food tents in the camping area and distributed its contents to passersby. The girl who worked the tent was helpless, so she joined the crowd.

“This,” she said, “is the best time I’ve ever had.”

At a 6 P.M. press conference, the promoters were already discussing the success of the festival. “All is well,” announced Scher. Oneida County Executive Ralph Eannace, Jr., exalted the promoters’ deft handling of the enormous crowd. “They said the wall wouldn’t hold, and it did. They said security wouldn’t work, and it did. It was a wonderful concert.”

Of course, the wall had long been breached, and the concert was far from over.

Around 7 P.M., as Ice Cube unleashed a brutal version of “Fuck Tha Police,” a thick line of thunderheads approached from the northeast. The sky turned a deep violet-blue. Lightning danced.

During Creed‘s set, someone drove a stolen white Mercedes-Benz through one of the many gaping maws in the Peace Wall up to a sound tower about 80 yards from the stage and ditched it. Security guard Tom Supernault—a 21-year-old local who says he reported to work Friday to find himself suddenly promoted to supervisor—got on top of the car and tried to stop the mob from rocking it back and forth. He was hit with bottles and fists from all sides.

The crowd gathered before the East Stage had swelled to an estimated 150,000. To the right of the stage, scaffolding, upon which about 100 people had been illegally climbing, collapsed. “It was suggested at this point,” said Charles Knapp, a moonlighting corrections officer, “that security turn our shirts inside out so they didn’t say ‘Peace Patrol’ anymore.” The youth-activist group PAX distributed candles to be used in an antigun peace vigil, a noble if egregiously underthought gesture. “There was very little security,” said Buthfer. “I saw maybe eight of them. They were looking at girls.”

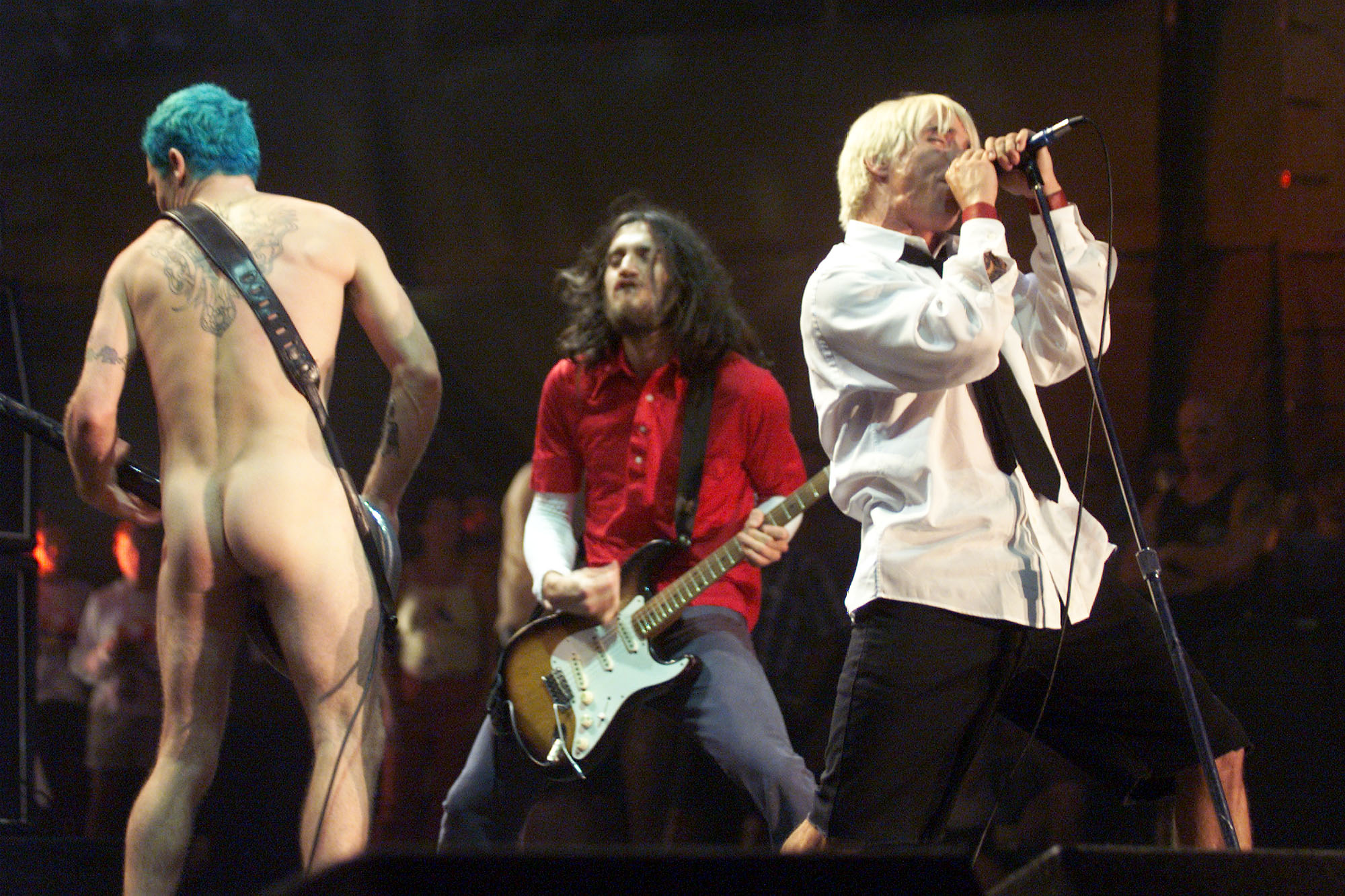

At 8:40 P.M., Red Hot Chili Peppers singer Anthony Kiedis came out dressed like a punk-rock schoolboy. Bassist Flea was naked. Perhaps in the spirit of things, and perhaps mocking the spirit of things, Kiedis requested that any menstruating women close to the stage throw their tampons at the band. There were no discernible takers. About halfway through the set, during “Under the Bridge,” all the PAX peace candles were supposed to be lit, a hundred thousand points of light espousing the professed ideals and virtues of the original Woodstock.

Two hundred yards behind the left side of the stage, a medium-size pile of a former mural was transformed into a medium-size pile of combusting cellulose. Within minutes, a second and third fire ignited in close proximity to the first. For most of the audience, only a glow was visible at first, but as the show progressed, the flames began to dance above the heads of the crowd. As the Peppers played an encore, Kiedis said, “Holy shit, it looks like Apocalypse Now out there.” They broke into Jimi Hendrix’s “Fire.”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”336606″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2019/07/GettyImages-539724230-1564362694-300×200.jpg”]

At this point, there were five large and swelling bonfires in the immediate vicinity of the stage. Smaller fires sprouted like weeds at more distant points on the field. The Mercedes was flipped over and set aflame. Via radio, security personnel were ordered by supervisors to retreat to security headquarters at Building 100. The band finished the song, and immediately afterward, a short multimedia Hendrix tribute played on the various Diamond Vision screens surrounding the stage. One hundred fifty thousand people waited to see what was next.

Throughout the day, there were rampant rumors of a secret grand-finale act. In the quiet after the Hendrix tribute, the crowd became restless and agitated. Would it be Pearl Jam? Prince? Bruce Springsteen? “Word got around that the surprise band was either the Rolling Stones or the Who,” said 19-year-old Justin Brake, “and people grew angrier!”

Soon John Scher took the stage, but not to announce a special guest band. “[Something] is on fire, as you can see,” he said. “It’s not part of the show. It really is a problem, so the fire department’s going to have to come in with a fire truck and put the fire out. Everyone needs to cooperate.”

The fire truck didn’t come. No surprise band took the stage. The concertgoers at the East Stage wanted more. And within the formerly walled confines of the former Griffiss Air Force Base, it was as if the top was ripped off the world.

* * *

About 200 people surrounded the area illuminated by the flickering yellow light of the largest bonfire. Athletic-minded crowd members jumped through the fire and yelled, “Fuck you! I won’t do what you tell me!”

Under attack, medical personnel near the East Stage abandoned their posts and took off their shirts. Security officially gave up the ghost. Those who hadn’t fled the site already were ordered to take refuge near the Woodstock management offices.

State troopers rolled in on four-wheel ATVs and attempted to push people away from the largest fires. After computing the police-officer-to-fire-appreciating-concertgoer ratio, the officers quickly retreated. On the PA system, promoters started playing Rage Against the Machine, which had precisely the opposite effect on the crowd as intended. Though most of the audience headed for the tents to leave, those who remained, five to ten thousand people, were determined to tear the entire site apart. On the West Stage, Megadeath were screaming through “Peace Sells.”

At 10:30 P.M., state police and a fire engine attempted to approach a bonfire but gave up when the crowd unleashed a missile attack consisting primarily of bottles. Ten kids rocked the 50-foot speaker tower next to the East Stage, shaking it violently. The cables snapped as steel bolts popped from their fittings. At 10:45, the tower came lurching down with a cacophonous thud. Young men climbed the remains of the scaffolding and banged on it like a victorious troop of chimps. Speakers and lighting equipment were hurled into the fire and exploded. A noxious cloud engulfed the area.

Around 11 P.M., the rebel army surged toward the center of the village. Police and security personnel were largely absent. The sound of yelling and chanting was everywhere. Almost 200 formed a drumming circle, banging on overturned garbage cans with their hands, chunks of wood, a sledgehammer, an ax. Cardboard and wooden pallets were added to the fires in the vendor area. Several storage trailers were set ablaze.

“There was one kid with a megaphone,” said 19-year-old Catrinelle Bartolomew, “who was saying, ‘Will everyone please pick up one piece of garbage and throw it in the fire?'”

A mob amassed on top of a beer-garden tent and collapsed it. A hundred people fell 20 feet but none were hurt. The tent burned. At some point, jocular rioters took control of a PA system long enough to declare: “Woodstock is now under martial law. Anyone here who has a good time will be shot. Anybody with a Woodstock MasterCard will be spared.”

Steel tent poles were used to break the locks securing several food-vendor semis. Kids tossed provisions to the crowd, mostly pretzels and snack food, which precipitated an extensive food fight. “It was raining pretzels and bread,” said Bobela.

The looting continued, spreading to the Ace Hardware trucks near the campgrounds. “People got in and basically started raping us for all we had,” said Bobela. “There was no physical violence, but it was all about stealing and vandalizing. All we could do was walk away. It was kind of like watching your house go down and there’s nothing you can do.” Even so, many vendors continued to do brisk sales in pizza. In the Rave Hangar, about 15,000 kids were still dancing.

The growing blaze of vendor tents, now fed by cardboard boxes, foodstuff, and assorted camping supplies, sidled up to the closet semi and engulfed it. Burning wood was tossed into the trailer, which was outfitted with refrigeration units consisting of volatile generators, propane, and coolant. The truck quickly exploded, shredding the sides and roof of the sheet-metal trailer and igniting other vehicles nearby.

Miraculously, no one was seriously injured in the blast. “Just imagine 12 tractor trailers on fire,” said Bobela. “From where I was standing in the parking lot, it was almost like watching a sunset—it was that bright.” Kids began throwing unoccupied tents and Port-a-Sans into the flames. Shit was literally burning. Women stripped for the crowd.

Someone stumbled upon a massive cache of glow-sticks looted from Ace Hardware. Kids cracked them open by the thousands. “We ran into these people who were having a glow-stick war,” said concertgoer Matthew Farrington, “and decided they were gonna throw glow sticks at the cops. So we go over there and they’re throwing them at the state troopers. This one guy was like, ‘Follow us, we’re gonna go kill the cops with glow sticks!'”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”336610″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2019/07/GettyImages-51066433-1-1564363122-300×178.jpg”]

By 11:45 P.M., 500 to 700 state troopers in riot gear had arrived on site, some wielding pepper spray. They successfully pushed the crowd away from the East Stage, but the campsite-area chaos continued unabated. There were an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 kids in the center of the base; some threw garbage at the police. The officers yelled at them but were not making any arrests.

“It looked like fucking Lord of the Flies,” said MTV’s Healy. “Kids were shouting, ‘Let it burn!'” The drumming continued. A teenage photographer paused to shoot some film of a young man being fellated by his girlfriend as a bonfire licked the sky behind him.

Near the vending areas, wild-eyed capitalists decided to make a withdrawal from the ATMS. “I saw people gathered around the ATM,” said Farrington, “and I just thought they were getting cash, but then I realized that they were breaking into it—with their bare hands! They didn’t even have any tools.” One minorly hobbled concertgoer attempted to use the blunt edge of his crutch to punch a hole in the metal casing.

After about 45 minutes, the kids successfully cracked open the ATMs only to discover what dozens had learned the easy way on Saturday: They were out of cash. As they walked away disappointed, people were smashing the little refrigerators in vending booths because they were there.

* * *

Mat Robin, a slight, brown-haired 22-year-old art-school grad from Toronto, had finally finished an hour-long rubbernecking trek through the fires to the Rave Hangar, where he and his friends hoped to see Perry Farrell spin. Security guards from the Rave Hangar had retreated to the ramp near the Woodstock offices at Building 100. Some of them began stealing boxes of CDs from the Rave Hangar, but they were halted by more virtuous guards.

Robin wound up on a raised patch of cement near the Rave Hangar in a group of 20 people. Nearby were some bales of hay, and not too far away were the ATMs, where the burgling hoard had been joined by a few men clutching bats and steel poles. “I was trying to stay away from that stuff,” said Robin. Someone tried to light the bales on fire. Robin heard a voice from the ATM yell, “Hey, put the fire out, we’re doing something Federal over here!”

A stranger handed Robin a five-by-three-foot flag on a seven-foot pole, and he began to wave it. He had no idea what the yellow sun on it meant. “It may have said ‘Rusted Root’ on the other side,” he joked. “I don’t know.” There were almost two dozen people with him, and they were talking, yelling, exchanging happy banalities.

The troopers were coming, several hundred of them, clad in riot helmets and shields, and they saw a man on a cement block waving a flag, yelling, near burning hay and the looted ATM area. They gave chase.

It took him a day in the county lockup to figure out why, and how deeply he’d stepped in shit. He faces charges of being a ringleader in the riots and of pelting cops with rocks and bottles. The police wanted to charge him with arson, but the lack of matches or a lighter on his person prevented that. Of the thousands rioting at Woodstock, and the couple dozen transported to county lockup with him, he was one of only seven officially arrested. He goes to trial in September.

“They’re trying to find some individuals [to blame], and there aren’t any individuals,” he said upon his release from jail. “It’s just the lemming effect, what happened. No one was in charge.”

Elsewhere, looting of the Ace Hardware trucks continued. Boys and girls ran around, loaded down with every imaginable type of camping gear. “Hey, everybody,” one of them shouted, “it’s Christmas in July!”

“When things were really raging,” said Bobela, “we saw a couple guys strip naked and start doing indigenous dances as if their whole life had led up to that moment. One guy climbed on top of a display speaker. He was giving a sermon like Christ—as if he was the chosen one, with his hands up in the air, yelling, ‘Praise me, I’m God.'”

Just before midnight, the all-night dance party scheduled for the Rave Hangar was canceled by the promoters. Perry Farrell was scheduled to spin. “Perry looked like he couldn’t believe it,” said Justin Hirschman, a booking agent. “Everyone was so disheartened. The DJs were like, ‘Why is this happening?'”

* * *

A phalanx of troopers, with a small contingent of moonlighting correctional officers who worked for Metropolitan Entertainment, managed to push the rioters back to the campgrounds. They cleared a third of the mile-and-a-half-long field. Every time they encountered a drum circle, resistance stiffened.

At 3 A.M., people continued to feed the campgrounds’ fires. Police let the rioters tire themselves out before attempting to fight the blazes. As a result, the Rome fire department did not gain control of the fires until well after dawn broke. At 4 A.M., the drumming circles finally broke up. As a haze of fog and smoke blanketed the area, most of the remaining revelers staggered back to their tents or vehicles, mentally preparing themselves to rejoin the quotidian pursuits of modern-day America.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”336616″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2019/07/GettyImages-97321660-1564363660-300×254.jpg”]

Feet black with dirt, hair matted and smelling of smoke, Pruitt got on her bus a little before 6 A.M. for the five-hour ride back to Connecticut. The next morning, Scher characterized the night’s events as “an aberration.” A week later, he floated the theory that a cult of indeterminate origin had orchestrated the rioting.

In the immediate aftermath, two concertgoers were confirmed dead, including DeRosia, who died of hypothermia on Monday; 5 rapes and sexual assaults were reported. “I was really surprised to hear that,” said Pruitt. “All the guys I was around were cool.”

A supervisor of two state troopers who had posed with naked female attendees was suspended; a New York State prison guard was charged with sodomizing a 15-year-old girl during the riots; 253 people had been treated at area hospitals. The official numbers of fans treated on-site is between 4,000 and 4,500, yet Dr. Richard Kaskiw, one of the few area doctors who worked the medical tents, says that he was told by Vuoculo—who issued the official stats—that the numbers were far higher, the 8,000 to 10,000 range. Forty-four concertgoers had been arrested. Damage and insurance estimates were still being compiled.

“Burning stuff isn’t the nicest thing to be doing, but it was justified,” said Pruitt. “They took advantage of us. I know they said the free water was fine, but I wasn’t going to drink it after getting sick on Saturday. I was forced into paying $50 for water that cost $1 in the supermarket. It was a way of getting back at them.”

Pruit said she never thought about what she was doing, or what could possibly happen. “The only time I thought someone could die was when the tower fell,” she said. “And yeah, I’d feel bad if someone did die, but I wouldn’t feel responsible. I only threw paper and plastic on small fires that were contained. It was a thrill I got to do anything I wanted to do and felt comfortable doing it. It’s like you’re a little kid doing something bad, but you’re not gonna get in trouble because nobody’s around.”

“I’ll tell you what, man, it’s a generation of ambivalence,” said the 19-year-old Cantrinelle Bartolomew. “We’ll all take a chance to live it up but intelligent enough not to hurt each other. Older people will never get it. When you look at Kurt and Serena on MTV, how scared they are—they’ll never get it.”

Mat Robin has no regrets. “It was insane—I’d never seen anything like it before in my life,” he said. “Our generation ain’t stupid. We’re going to get our money’s worth, then riot.”

Pruitt is nothing short of wistful. “It was an amazing, incredible experience,” she said. “Just to say that I saw all those bands. And those fires.”

Additional reporting by David J. Prince, Mark Spitz, and James Jellinek.