This article originally appeared in the January 1987 issue of SPIN.

There is this guy, call him Goatman, because that’s what he sounds like. Here is what he sounds like on a tune called “Emthojeni Womculo”: ow wow ooowwwww. He is Howlin’ Wolf as pedagogue, a patient, preachily voice moaning out a Zulu rap about the universality of music, how it has no beginning or end. Like that.

There is this other guy, Paul Simon. He doesn’t sound anything like a goatman; he doesn’t sound bluesy, not tutorial, not low. When Simon brought some of Goatman’s confederates to New York from Soweto last year to record the new Graceland album, upon arrival one of them asked where he had to go to register with the police. Simon had a lot of explaining to do.

Graceland is for the most part a record of South African rhythm tracks, bouncing underneath the kind of the kind of stuff you’ve heard Simon talk about before. And in exactly that Simon voice: somebody I asked for pre-interview advice just said, “Ask, ‘why did you sing on the album?'” This is not, however, why Simon has been doing a lot of explaining since Graceland came out.

I always hated Paul Simon. He put enough cheek into the pooped-out urban despair of the ’70s to give a lot of people the excuse they were looking for the feel good about feeling bad. Self-absorbed, seemingly comfy in his ennui instead of trying to blowtorch it out of his heart—God, what a target.

Shit like “My Little Town” and “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” and “Slip Slidin’ Away” was real shit, a good inside joke at the pagan worship of singer-songwriter geniuses. And there’s that milk-shake voice. Where’s the backbone?

* * *

Are you a mets or a Yankee fan?

I’m both. I grew up being a Yankee fan, but I root for the Mets in the National League.

Oh yeah, sure!

Here’s why Simon is explaining Graceland so much these days. In South Africa, it is easy to find the “township jive” that he loves and puts forth on Graceland; it’s on the radio far more frequently in many areas than, say, Michael Jackson or Run-D.M.C. The apartheid regime finds it useful to promote this raucous music, with its cheerful descriptions and parables of township life, which supports the government’s idea of what simple, folksy people the “homeland” dwellers are.

American black rock and pop, which might suggest an international black heritage and unity, are restricted by the government-controlled South African Broadcasting Corporation. The day “Dancing on the Ceiling” is blasting through the South African streets may only be the day they’ll be dancing in the streets, on the ceiling, on the bones of the regime.

Apartheid aggressively monitors pop music. While certain cuts from Simon’s album get played freely in South Africa, other interracial efforts aren’t always permitted. (Big exception: “Ebony and Ivory,” which went No. 1!)

Two members of the South African reggae band Scratch were sentenced to four years behind bars in 1983 for “indirectly further[ing] the aims of the African National Congress.” From the stage they had called for the release of Nelson Mandela. It is illegal, of course, to play the Special A.K.A.’s “Free Nelson Mandela.”

There are some important objects to weigh in thinking about the pleasures of jive. Besides wearing, at least for the moment, the regime’s seal of approval, it doesn’t much benefit the black musicians who make it. Sales abroad finance the white-controlled music industry; royalties to blacks are rare. Sipho Hotstix Mabuse, one of the musicians thanked on Graceland, had his equipment destroyed by anti-apartheid activists last year for collaborating with the music industry at a “People’s Concert.”

But then, there are the gifts of Goatman to weigh, too. And more important, some form of unity has been forged by this thumping, clattery pop music. It’s shaping an audience, even generating a tiny, dogged black music industry. These bonds may not always be to the regime’s tastes.

Jive is the root; its rockingest spin-off is mbaqanga. The sound started after World War II, when Zulus and Sothos working in industrialized townships merged folk forms with shit like old Lionel Hampton, Ray Charles, and Louis Jordan records. They played pennywhistles. They dug accordions. The traditional music broadened, splinters of R&B and jazz working into the beast until they were utterly absorbed. But they were way mutated too. So what you end up with is some of the strangest dance music around today, stuff in no way drum groove metameta like juju, not rife with James Brownian motion like highlife.

Naw, when Simon says this music reminds him of rock ‘n’ roll, I take it to mean he’s thinking of mbaqanga’s keen aesthetic of the three-minute composition, it’s unself-conscious and exuberant voices, it’s immediacy. There is, further, it’s astonishing rawness: “What the Nominalists call the grit in the in the machine, I call the fundamental element of the machine,” said philosopher T.E. Hulme, and doubtless South African groups like the New Lucky Boys, Nelcy Sedibe, Mister King Jeroo, Moses Mchunu, and friends would agree. Jive sounds anything but developed, like it was invented minutes ago: music with a future.

“Roll back the carpet, put on a record, and jive baby jive,” sayeth the liner notes to Phenzulu Eqhedeni (Carthage), which like Soweto (Rough Trade) and The Indestructible Beat of Soweto (Shanachie) is a good place to start digging this floor-dusting. This music will last, for sure, even though the musicians won’t see any money, and even though the government enforces its Sunday Observance Law (no work on Sunday), which along with work-week jobs ensures that recordings are done after hours or illegally. It will continue until the carpet is pulled up.

Paul Simon’s airplane-hangar-sized office in the Brill Building in Manhattan is filled with memorabilia: a giant photo of Johnny Ace blown up from a promo pic Simon sent away for as a kid; guitars; artifacts dating back to his Tom and Jerry days. He’d insisted on seeing stuff I’d written before he’d jaw, but from his handshake on, I’m disappointed to find myself in the middle of a swimmingly enjoyable afternoon conversation.

Simon sinks into a soft chair—and those diminutive guys can really sink—stares off, and gives all of my questions calm, considerable though. What I first take for nervous pauses in the conversation are, in fact, meaningful lacunae. For a guy who’s more New York than You Hoo, he is one uncrushed singer-songwriter. He listens attentively and truly likes to talk—after the interview he gestures for me to stay and chat about SPIN, Mario Cuomo, making another movie, and the California Angels. He doesn’t try to dick me with his star power; he’s smart, friendly, pleasant. Which only goes to show that it’s not a good idea to talk to too many people—because then you can’t hate them so much.

You’ve said that jive reminds you of ’50s rock ‘n’ roll.

Yeah, a little bit. That’s the best explanation I can come up with for some intuitive and emotional feeling. It does sound like that, and I do like that music and am able to relate to it, but there’s some other inexplicable thing in it, too. So I just want to leave it as “quasi-’50s rock ‘n’ roll.” There’s something else in there, but I don’t know what it is.

Tell me about some ’50s rock ‘n’ roll that’s influence you. Sam Cooke?

A big influence. First, I think Sam Cooke was the best voice. I don’t think anybody was in Sam Cooke’s league. And he also tended to be more of a soft singer and phraser, so there was more for me to learn because that’s what my voice is naturally.

Although he could belt too, essentially for me it was the smoothness of his voice. I was a big Sam Cooke fan, still am, even more for his work with the Soul Stirrers than for his pop stuff.

What about Elvis?

Yeah, Elvis was there. He was the most important force in rock ‘n’ roll, no question about it. Nobody even close. It was his invention, he blended black and white music, and that’s the single most powerful idea that’s emerged from rock ‘n’ roll. Plus he had the voice, a great investment.

Other stuff? The Everly Brothers, too—wouldn’t have been a Simon and Garfunkel without the Everly Brothers. Doo wop groups, we sang in doo wop groups when we were kids. We learned about singing all the three different parts, from bass to falsetto. I still do that on all my records, still put in all the background vocals myself.

Tell me about the song “Graceland,” which has a metaphor of a car trip through the South to Elvis’s home. It sounds like the trip is a real report. What was it like to go to Graceland?

Just as in the song, the journey was more interesting than the destination. The drive up the Mississippi Delta is very beautiful. I had been recording for this album with Rockin’ Dopsie in Louisiana. I rented a car and drove up. It was very beautiful—Louisiana, the rural South—and I hadn’t been there in a long time.

But Graceland itself was just a business. Big parking lots, you buy your ticket, get on a bus, and wait in line. There’s a tour, guides, and they take you through the house and show you Elvis’s this and Elvis’s that. It’s a very common experience, but nevertheless, at the end, you come out onto the grounds and there are the graves of his mother, his father, and him. Even though it’s so commercial, you could even feel it offensive to your taste—and then, on the plaque on Presley’s grave, it says he was given the gift of this incredible voice that has touched millions of people all around the world. And that’s just what it is. A gift.

You heard a tape of jive and wanted, you have said, to go to South Africa to find out who the musicians were and how they lived. Who were they?

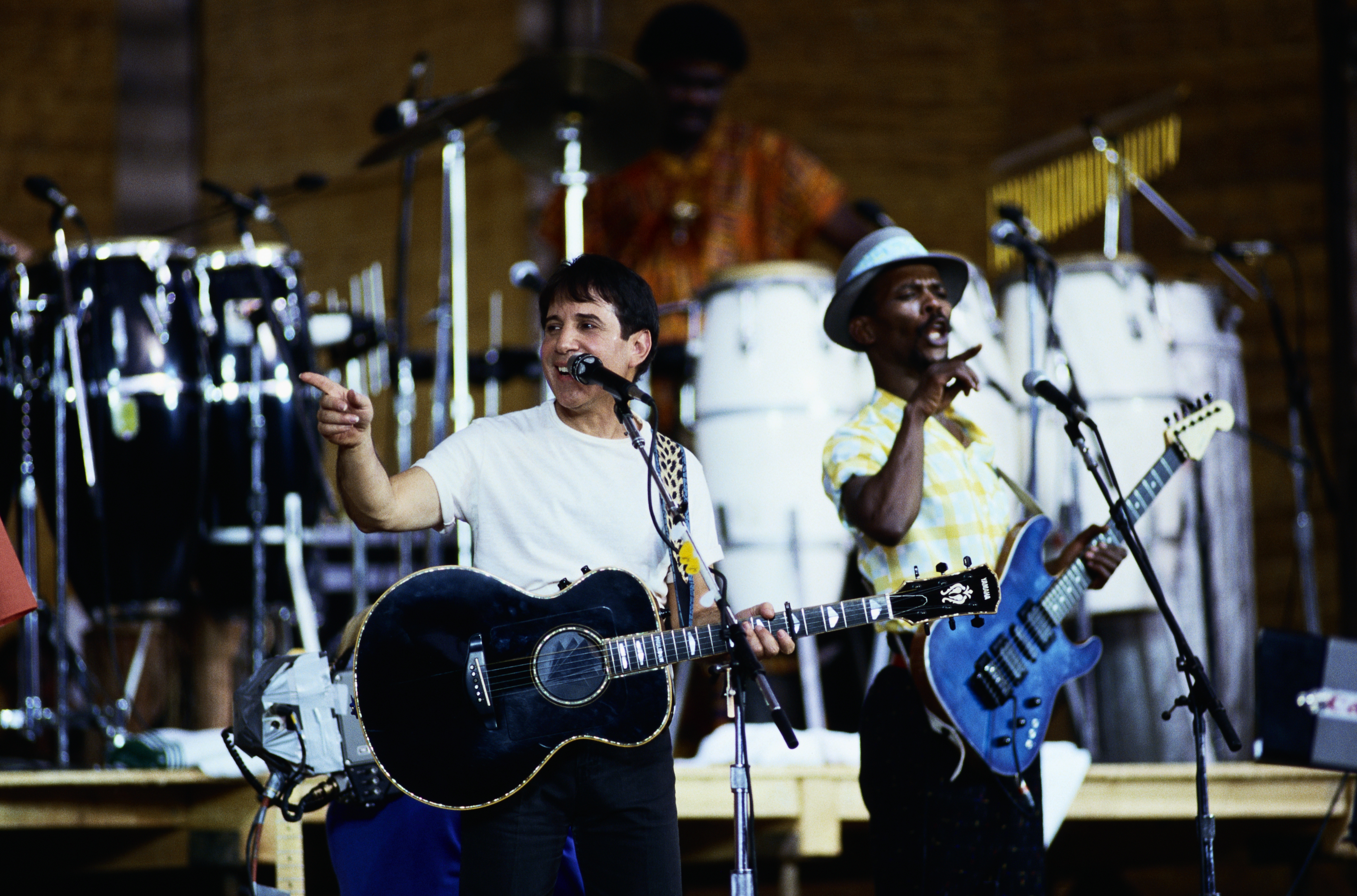

They are a varied group. Some of them were players who lived in Soweto and who were part of popular bands there. Those are the guys I worked with most and those are the guys I brought back to New York to record and to perform on television. Some of the groups come from small, out-of-the-way towns: Tao Ea Matsekha and General M.D. Shirinda, not really well-known groups, who play a different style of music. Tao Ea Matsekha plays a Sotho style of music, General plays Shangaan style.

For the most part they don’t speak any English, so I didn’t get to know them like I did the guys from Soweto, who did speak English and were much more aware of American music. And who had more of a typical musician’s chops, unlike General and Tao. Then there’s Ladysmith Black Mambazo, just this fantastic sounding group.

Tell me about them: a Zulu gospel group, obviously all spirit, not at all like ’50s rhythm and blues. Did they express any trepidation about working with a Western pop musician, mixing their sacred with your profane?

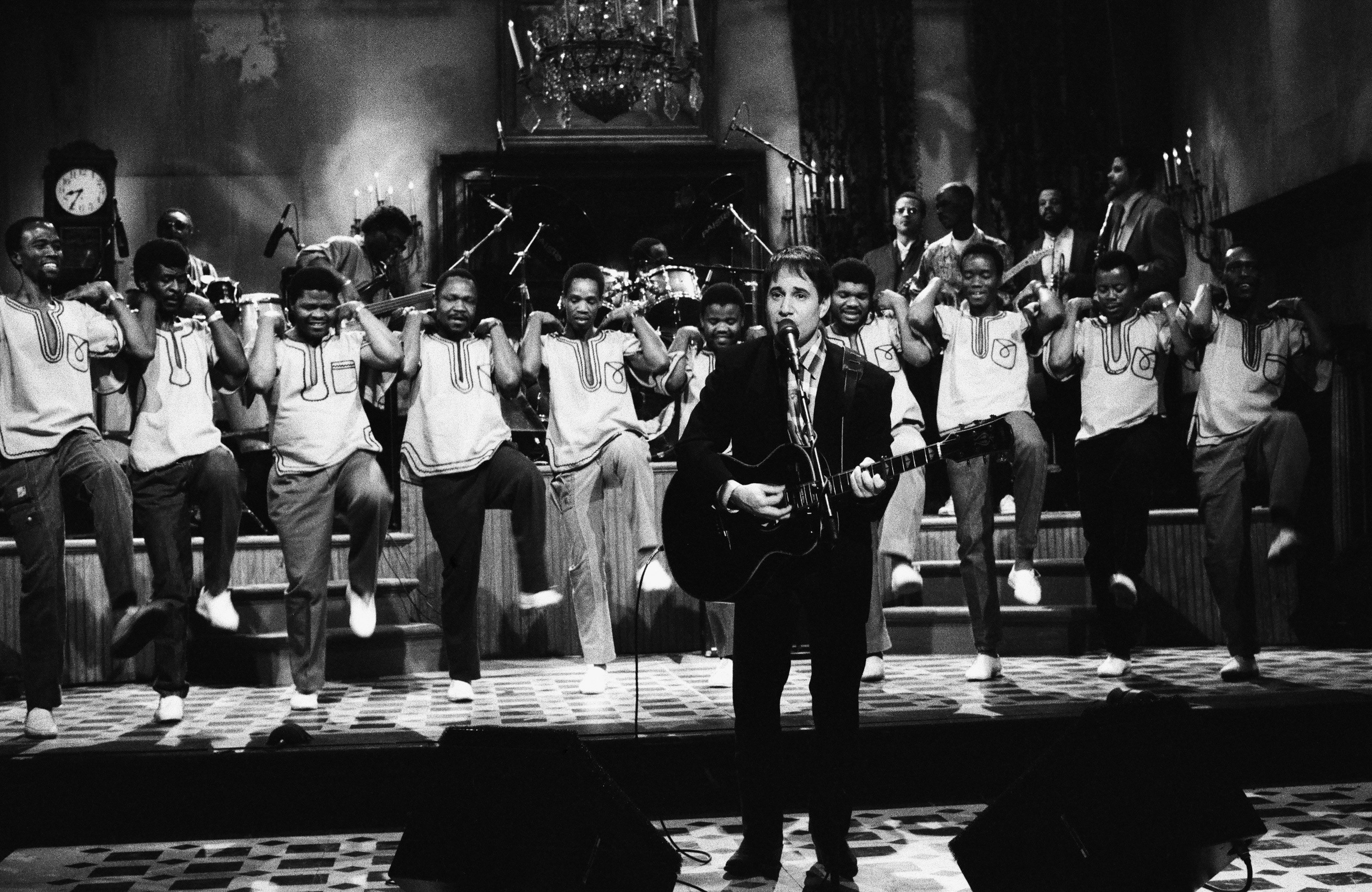

No, because they have done that before. They have sung in English, they have many records out. They must have 20, 25 albums. They are a church group—the leader, Joseph Shabalala, is a reverend. They come from the township of Ladysmith, near Durban. They are Zulu. Joseph handles all the choreography.

It’s very much like storytelling. It’s very intricate, and all the songs have choreography. They all dance in unison in very interesting movements. Joseph writes songs about what happens in his life every day. He carries a notebook with him always. He writes phrases and thoughts, and he tends to write songs pretty consistently, and they are what happened to him that day and week.

Tell me about the reservations you had about making the trip. You were, by the book, breaking the letter of the U.N.’s international cultural boycott of South Africa.

The only reservations I had were that I didn’t want this trip to be misconstrued, to be thought in any way to be in support of the policies of the government of South Africa. I wasn’t going to perform, so in that sense I thought it was within the guidelines of the cultural boycott, although technically I wasn’t, as it turned out.

I don’t think the boycott was intended to block black South African musicians from access to the international music community. I think it was to block the white, discriminating community there from outside nourishment. Whether that is an effective means of bringing about social change remains to be seen…

But I certainly support the cultural boycott as a means for the artistic community to express moral outrage. But on the other hand, the de facto black musicians union over there is very frustrated at not being able to get their music heard in the world community They felt they were the victims of a double apartheid, where they were being repressed at home, and then when they were trying to get their music outside, people were resistant to it because they were South African. They just felt that with me, having access to world markets because of being well known, they could get attention.

Don’t you think it further confused the issue of your stance on apartheid to do a duet with Linda Ronstadt, who played Sun City?

Linda Ronstadt in no way supports the apartheid regime. I don’t think she believes in the cultural boycott. She thinks that there are other ways, ways of sending ideas into the country, exposing people to them. I don’t think Linda Ronstadt would ever play Sun City again. I know her politics and don’t think it’s incompatible to put her on the record.

But again, I think this record is about, primarily, music, and only by inference about politics. It doesn’t take a stance on whether Buthelezi should be given a voice in the leadership as opposed to Mandela, or whether Desmond Tutu can unify. It doesn’t deal with those issues or the politics of South Africa, because I really am in no position to comment on them. I don’t know about it enough, and my entire trip was about two weeks, and the time was spent in a recording studio.

What do you think of blunt, political statements like the Sun City record?

I think in principle this idea of politics, which is suggestive and open-ended, can be more powerful than the newspaper headline of “Don’t Play Sun City”—blunt, narrow.

There is a difference in what messages are conveyed by the different media. What you can say in an editorial on TV or in a newspaper has a different impact, a different tone, when you say it in music. They say they made it to make people aware of the situation. And it probably did make some people more aware, although it’s something that’s on the news every day, and if you are talking about reaching an audience that doesn’t read the papers or watch the news, then I don’t think they really care about it anyway. So I’m not sure how effective it is. But to whatever degree it is effective, that’s great. It helps. But personally, I didn’t play Sun City, and I was asked to play Sun City. I turned it down. I don’t know whether the Ramones saying, “We ain’t gonna play Sun City” means anything, because nobody ever asked them!

But as a symbolic gesture, it adds weight, it adds momentum to the anti-apartheid movement. I think my record also contributes to that, but in a different style. It definitely adds to the feeling we have about South Africa, to the motion toward the political situation.

Well, not necessarily. It doesn’t add to the feelings Jerry Dammers, who wrote “Free Nelson Mandela,” has about the country. Dammers has had strong words in Britain recently about Simon’s efforts. He is far from alone. Nothing obligates Simon to take a stand—except history, the history working out now in South Africa. There is precisely one song on Graceland that addresses the facts of life under apartheid. “Homeless” says: those without shelter in South Africa are tragic victims. And…that’s all.

This album could mean many things, or nothing, to all kinds of people—those pro- or anti-cultural boycott, yuppies with money invested in apartheid, the apathetic, the New Republic reader. Choosing to think of South Africa as predominantly a set of great musical traditions is valid in a way, but another South Africa keeps intruding: the one on fire. Who knows what will happen next Friday, next year? It’s easy to believe that history will kick this man’s ass.

No, in the long run, this isn’t much of a South African record. African sounds may be the bones of Graceland, far more than salsa, say, was the key to Simon’s Latinized “Late in the Evening.” But this is not the Goatman’s record. Simonizing the jive’s rawness with 48-track production, the album is tasteful, the sound not jumping. It’s not that the process kills the beats, but it redefines them, pushes them into the background. This is a singer-songwriter’s album, yeah: its themes are random New York encounters and not much less random love.

How things like a (metaphoric) good beat and decomposing bring us together. Here’s the best thing mbaqanga, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Sunny Ade’s great steel guitarist Demola Adepoju, the pennywhistler Morris Goldberg, and so forth, did for Paul Simon: they gave him the strength and playfulness he needed to fuckin’ cheer up. At last, no more wavelets of pretty misery and sobriety and gravity and feh washing over you.

Graceland‘s better than that. The music does have a swing to it, and a goofy thing like “You Can Call Me Al” works in all the ways that the equally goofy “50 Ways to Leave You Lover” never did. It’s about a silly, beautiful pennywhistle solo and salvation and the things that can connect them.

Simon has said there’s a line in “Graceland” that freed him: “Losing love is like a window in your heart/Everybody sees you’re blown apart, everybody sees the wind blow.” Having said it, he was free. Having signed on a lot of great musicians, working to make sense of a lot of varying traditions, he doesn’t just say he wants grace, he shines a little of it in your face.

He’s listening to the Jesus and Mary Chain, the Smiths, and the Cocteau Twins. he says he wouldn’t ever want to put a self-censoring sticker on a record. He’s pretty down on contemporary hit radio, on the vagaries of the music industry today.

“The bigger the corporation, the more pressure there is to be a mainstream act,” he says. “And that act today is not very daring, it’s not gonna be controversial. That’s what life is. That’s the truth. And you can battle, and you might win, but you will definitely have a fight on your hands.”

Even so, he doesn’t sound down about it, doesn’t inflect the conversation with a trace of the petulant lassitude that soaked One Trick Pony‘s anti-biz script a few years ago. This is a different guy. It’s the difference one goatman can make.