This article originally appeared in the September 1985 issue of SPIN.

Jesus Christ, life is depressing. It’s surprising that anyone bothers to carry on with it. And when everything seems hopeless, someone tells you it’s bound to get worse. You know. You wear a pin that says “Life sucks, then you die.” The epidemic of teenage suicides in this country doesn’t shock you because youth is no excuse for living.

You can understand why Ian Curtis hanged himself, aged 23, the night before Joy Division was scheduled to start its first American tour. His lyrics were haunting, his grief-filled voice unique. But who cares? When you’re hot, you’re hot; when you’re sad, you’re sad.

The death of this unassuming singer with faraway eyes was considered Very Important Indeed. Joy Division was to England in the ’70s what the Velvet Underground was to America in the ’60s. Both bands attracted a fanatical cult following, and both had charismatic lead singers whose overriding artistic motivation was a fascination with the button labeled “Self-Destruct.” Some neurotics fulfill their own prophecy, others make Honda advertisements.

You can hear Curtis’s suicide notes on the album—in the hypnotic despite of “Digital,” for instance: “I fee it closing in / Day in, day out / Day in, day out / Day in, day out.” Or “Isolation”: “I’m ashamed of the person I am / Isolation. Isolation. Isolation.”

The death-march quality of “Means to an End” makes it the gloom song to end all gloom songs. Joy Division’s music was stark, abrasive, sometimes simplistic, and (like the Velvet Underground’s) one of the most important influences of the era. You can hear it in Sisters of Mercy, you can hear it in the Smiths, you can hear it in Echo and the Bunnymen, you can hear it in Bauhaus. Now a whole generation of self-obsessed white wimps on Valium is plaguing us with its torment and loneliness. Hear Tears for Fears, for goodness’ sake: “I find it kind of funny / I find it kind of sad / The dreams in which I’m dying / Are the best I’ve ever had.”

Curtis’s death perpetuated the myth that was already beginning to shroud the band. “It’s the perfect end, isn’t it,” says bewhiskered and apparently undepressed bassist Peter Hook. “It’s like the Doors. It makes him perfect. It makes it all so glamorous and awe-inspiring. It makes the band really appealing.”

The band is New Order now, of course, not Joy Division, but the early ’80s saw it doing little to destroy a carefully constructed legend. You don’t see beaming boys-next-door staring from New Order album covers. Indeed, Peter Saville’s classical packaging does not give the curious fan the benefit of credits, let alone a lyric sheet. “The songs are not statements,” explains Hook. “We don’t separate the lyrics from the music.”

Factory was their fortress. That Manchester-based record company was founded by maverick entrepreneur Tony Wilson, whose gray-jowled policy relies on action: “We do something because we want to do it and find out the reasons for it after we’ve done it.”

Independent labels weren’t unusual then, survival was. Set 200 miles from London (still the heart of the British music industry), Factory refuses to give bands contracts, advances, or hype. It believes that if you have talent, you can make it.

New Order members reap 50 percent of the profit from their record sales, and since they are the world’s best-selling independent band, they are not badly off. No swimming pools, but “we can borrow money to buy cars,” laughs Hook, “and we can do a lot of things that other bands and independent record companies would like to do.”

Like refuse to give interviews, for instance, something that helped the legend. They remain shy of the media, despite being the personal idols of most English music journalists. Consequently said writers, starved of bare facts, are inclined to eulogize the band and overintellectualize its output. When New Order played its first concert in London in 1981, Paul Morley told New Musical Express readers he “burst into tears” (not from boredom, presumably).

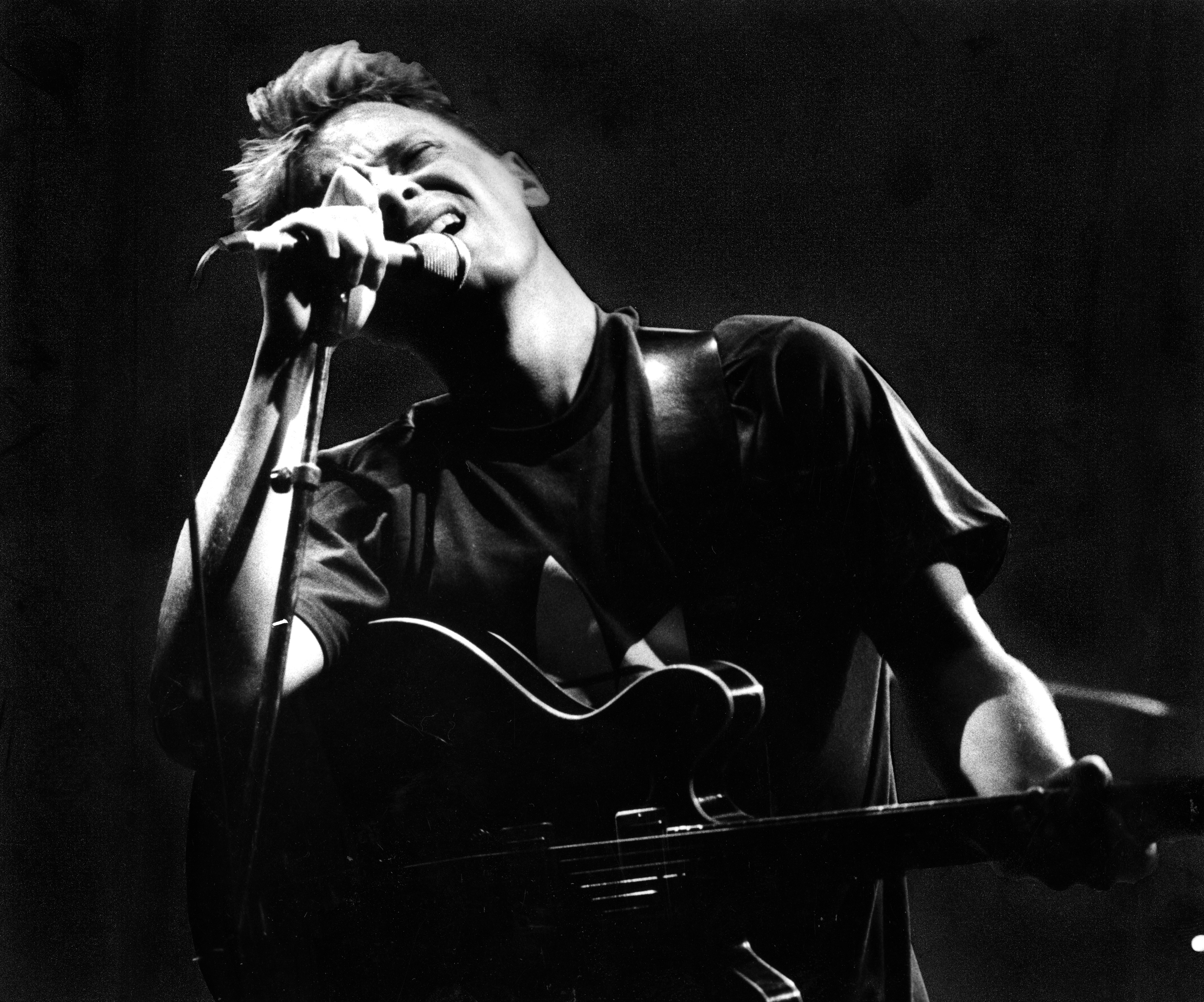

Even recently, another writer called them the “driven snow of the soul.” Writers always felt there was a lot to say about New Order, but the band’s material did not always live up to that expectation. That’s because when it comes down to it, New Order is not grandiose or obscure. It is a down-to-earth group with a cute vocalist who sings nicely and a batch of charismatic dance tunes.

“What appeals to us is simplicity,” says Hook. “Our music is complicated, but you get a nice, simple feeling from it.” That feeling is largely due to his bass lines, which married to precise drumming by the darkly domineering Stephen Morris, form New Order’s musical character.

Bernard Sumner’s lead guitar usually takes second place. Their inclination toward sameness stems from unashamed use of disco rhythms, which spawned the commercial success of hits such as “Blue Monday.”

With the release of Low-Life, the mist around this band may lift. They have placed their faces, albeit artistically distorted, on the sleeve, although it is typical that drummer Morris, and not vocalist and star-apparent Sumner, grace the front.

The excellent video of “Perfect Kiss,” directed by Jonathan (Stop Making Sense) Demme, focuses point-blank on the individual members and their musicianship. “No models, no smoke bombs, no Mad Maxes here,” says Hook. Just three intense-looking men and a red-headed woman playing out their concentration spans in a Manchester rehearsal studio.

Demme’s camera zooms in on their features and fingers, which, in keyboardist Gillian Gilbert’s case, are playing a melody comprising about six notes.

They are untrained and proud of it, like the old blues players who when asked if they could read music replied, “Not so it can hurt.”

“It gives you more freedom to play what comes from within. Mind you, my fingers won’t go in the right places most of the time,” admits Hook. Adds Morris, “As long as what you’re doing is good, you don’t get frustrated.”

The lyrics have always taken second place to mood and music. Sumner’s quavering tones are often mixed in production so they are heard below the instruments. Try to sing along to “Perfect Kiss.”

“Often when a song is semifinished, we just go out and play it,” explains Hook. “We’ll jam the lyrics. It works quite well sometimes, but sometimes it’s really embarrassing. There’s always a string of obscenities. But as long as you look as if you mean it…as [Factory’s] Tony Wilson always says, ‘It’s Aaart.”

This disorganization, which borders on arrogance, is, of course, endearing. Journalist Chris Bon, who toured with New Order in 1983, recalls a typical scene: Hook failed to show up at a concert in Washington, D.C., because he had passed out after drinking melon-ball cocktails.

Manager Rob Gretton, who has a face like a leek, halfheartedly and unconvincingly stepped in. A couple of songs through the set, Hook turned up and greeted the audience cheerfully: “Hello, shitheads.”

Now New Order is doing business with Qwest, Quincy Jones‘ label, which boasts the considerable advantage of being distributed by Warner Brothers. They can look forward to the rerelease of Power, Corruption and Lies. MTV. An extensive summer tour. Back-to-back interviews. Paparazzi fighting over them. Will New Order become Pop Stars? Will they remember the fans who braved New York’s East Village to see them in the Ukrainian Home? Will they go on Solid Gold?

“The single wasn’t engineered to be commercial,” says Morris in his North England burr. “We didn’t think, ‘Right, we’ve got to write a commercial song.'”

“Anyway,” inquires Hook, “What does commercial mean? ‘I’ve heard it a lot of times and I like it,’ or ‘It doesn’t sound like Einstürzende Neubauten’?” No. Commercial means you could run the risk of becoming the next Police.”

“The deal with Qwest is not what it seems to be,” explains Morris. “We’re not signed to them We’re not in a position where they can exert a tremendous amount of influence on us. They approached us. A lot of people who wanted to sign us didn’t want to give as much control as we wanted, and to compensate for that they offered us more money, but it didn’t seem a fair deal.”

“The deal we got with Qwest seemed the best because of who they were and because they were interested in what we were gonna do.” And, adds Hook, “It’s quite flattering the Quincy Jones thinks our record, which we produced ourselves, ranks alongside his. That’s a compliment worth waiting for.”

So what are their motivations now? They’ve been in the business for eight years, they’ve achieved adulation all over the world without having to wear silly clothes, they can play Hawaii because they want to. They’ve made money and put it back into their hometown (they own the local Hacienda nightclub).

Morris: “We don’t really hope for anything, just that we will continue to be around and able to do this. It’s nice if people buy your records, you know, but you don’t desperately want it. All you want is the means to carry on with the next thing. I haven’t really got any illusions about stardom in America. It will just be more of what it is now, and we will have to deal with it pretty much the same way.”

Sumner and the rest of New Order are too clever to want stardom—they always have been. They haven’t sold out, they are merely learning and progressing, which is (and I’m only guessing) what life is all about. That and optimism (“Let’s go out and have some fun,” sings Sumner on “Perfect Kiss”).

Anyway, how can you doubt a guitarist who says, like Hook, that the highlight of his career “was this fight I had at the Factory. Me and this roadie had been out drinking. This kid hit this kid. I thought, ‘Fuck this,’ fell off the stage, and kicked the shit out of him. We got him to the back and he was yelling, ‘No, no, I’m a Joy Division fan.'”