This article originally appeared in the December 1985 issue of SPIN.

What is “new-age” music? Is it music that’s made for meditation, stress reduction, and massage? Or is it whatever California’s post-hippie generation or the yuppie crowd happens to be listening to at the moment? “New age” is a difficult term to pin down, and you certainly don’t want to ask the artists themselves, because they tend to describe their music like this:

“Spatially enhanced flamenco guitar channeled via electrocrystals thru deep digital reverb into the spaciousness of a thousand and one reflections.”

Excuse me? New-age music may be hard to define, but it’s easy to spot; words like “deep,” “cosmic,” “harmony,” and “bliss” in the liner notes are a dead giveaway. This particular gibberish is from an album—an enjoyable album, actually—by guitarist Gino D’Auri.

Ray Lynch, another purveyor of music meant to expand your mind, quotes from a new-age book in the liner notes from his lovely but uneven recording Sky of Mind. This presumably explains where his music is coming from: “the mind is like a cave of bats.”

Nice, huh? But wait, it gets better: “Countless eyes are suspended in darkness, with sharp feet clinging to the convolutions of the brain, hiding from light” (or, as Monty Python says, “the human brain is like an enormous fish. It’s fat and slimy and has gills through which it can see”). This is not only to get you worked up about hearing the record, but also to prepare you for the enlightenment the recording supposedly will deliver.

In the notes to his album Planetary Unfolding, talented synthesizer player Michael Stearns lets us in on his inspiration: “I had a dream about the earth. In my dream the earth wasn’t a solid mass, but a mass of sound held together through resonance….Suddenly, I and some others were shot out of the earth’s resonance. We were sound vibrations, too…Then I became aware that the cosmos as a whole was, itself, a vibrating orchestration. The resonance was so complex and deep [the magic word] that I couldn’t hear anything. I felt engulfed by a vast and tender silence. Yet I heard one small sound, almost like a moist breath. As I awoke I realized that moist breath was the earth.”

Or maybe someone spat on him while he slept. Still, none of this tells you anything about the music, although by now you may have a pretty good idea of how it sounds. Much of it uses flowing, melodic synthesizers, though solo piano is common, too. Bells are a favorite, as are Indian drone instruments.

Despite its tendency toward fluffiness, a lot of fine new-age music exists. Sometimes it’s good despite itself. Steven Halpern is one of new age’s most successful artists. His liner notes proudly proclaim that “unlike most other music, from Bach to Rock, the music on this album has no driving beat or compelling harmonic or melodic progression.”

Sort of as if the Pringle’s people claimed their potato chips were “completely free of all nutritional value!” Just think, with Halpern’s music you’re safe from the mind-wrenching complexities of compelling harmonies and melodies, right? Well, no, not really. Halpern occasionally slips in a bona fide piece of music. It doesn’t happen often—and I’m sure he’s just sick about it—but some of his recordings actually have moments of interest.

My favorite album note: “this recording is for relaxation, and may cause drowsiness. It is not recommended for use while driving or operating machinery.” This is from A Rainbow Path by Kay Gardner, an intriguing album containing orchestral instruments, drones, and voices.

The notes are yet another example of the silliness and pretension that surrounds new age. But at its best, new-age music is extraordinarily beautiful, and a real eye-opener to listeners who didn’t realize that such music even existed; at worst it is insipid, vacuous drivel that can lead to brain damage. Musical mumbling and corny nonsense can turn off potential listeners before they ever hear the music. However, Kay Gardner’s music will not make you drive off the road; it will not cause you lose your fingertips in the pencil sharpener. You may enjoy the music.

Since you’ll doubtless be hearing more of these artists in the near future, here’s a brief rundown of some of the major new-age figures. I’ve tried to take their records on purely musical terms, ignoring whether they’re designed to relax you, turn you into a Moonie, or induce acid flashbacks.

* * *

Kitaro. The underground king of new age, Kitaro is from Japan, where he lives and works in a remote mountainside village. He makes lush, colorful music with synthesizer, guitar, and some percussion, and at first sounds a little like Vangelis. His finest recordings include Silk Road and Tunhuang, which thankfully involve a relative lack of pretension; but after these two, his many, many albums begin to sound alike.

Iasos. This Greek-born composer now lives and works in California, the Disneyland of new age. His earlier recordings (cassettes only) rely heavily on natural sounds—wind, rain, birds. His later work with electric flute and synthesizers is more musical. Elixir is an especially beautiful collection, though marred by the usual “ethereal-creatures-will-inhabit-your-nasal-cavity” liner notes.

Paul Winter. In many ways Winter, who has never used a synthesizer, is the granddaddy of new age. Since the late ’60s his music has combined jazz, rock, and classical influences with such new-age concerns as Indian music, conservation, and wildlife recordings. His best works are Icarus, which features most of the members of Oregon, and Sun Singer, a very mellow album with sax, organ, and occasional percussion.

George Winston. Solo piano, and not a single one of the many Winston clones does it as well. Winston plays watery, impressionistic compositions for the Windham Hill label. His background in folk and blues would seem to support Windham Hill’s claim that this is not new-age music, but that’s not otherwise apparent. Winston’s remarkable trilogy Autumn, December, and Winter Into Spring has gone gold and remains a favorite with new-age listeners.

Andreas Vollenweider. This Swiss harpist also claims not to be a new-age musician, but he is.

Deuter. This German musician lived in India for many years. Apparently a confused young man, he was a follower of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. When Rajneesh’s unwashed hordes descended upon and overran a town in Oregon, Deuter settled on the West Coast. He plays synthesizers, guitars, zither, bells, and just about anything else he can get his hands on. He’s developed a versatile style that ranges from placid and ethereal to energetic and percussive; on his best album, Cicada, Deuter lays down a rapid Tangerine Dream-style beat in one work, then follows it with a slow, graceful piece of electronics. Nirvana Road and Ecstasy are the best of the rest.

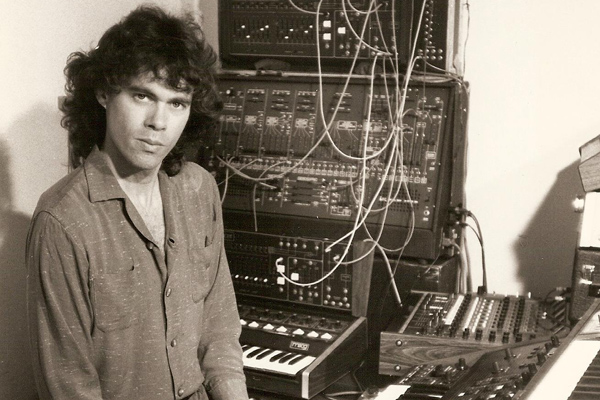

Michael Stearns. This California-based synthesizer player uses such oddities as the kantele, a folk harp from Finland, and the lyra, a set of long, amplified wires strung from floor to ceiling in a large room. His music can be tedious, but much of Planetary Unfolding, most of Lyra: Sound Constellation, and parts of Ancient Leaves and Light Play show a real mastery of his instrument(s) and generally dependable musical instincts.

Don Robertson, Kevin Braheny, Steve Roach. Substitute any of these names for “Stearns” in the previous paragraph. In fact, I suspect they’re all the same person. Actually, these three are also fine synthesizer players. Roach’s Now and Traveler, with their prominent synthdrums, are much closer to rock than most new-age music. Braheny’s Perelandra and Roach’s Structures From Silence are all superior albums of floating, cosmic electronics. Best bet: Robertson’s Starmusic and Spring.

Thousands of musicians have been lumped together, correctly or not, under the new-age umbrella. Some are worth hearing; some are not. But new age’s startling commercial success during the last three years proves that many people are finding it worth knowing. Don’t be put off by the blather that accompanies these recordings. Like any other style, the only way to find what’s good is to sift through the material that’s available.

And may thousands of glowing notes of musical bliss expand your consciousness, bringing electronic harmony to your existence and infesting your eardrums with the deep resonance of the eternal cosmic yawn.