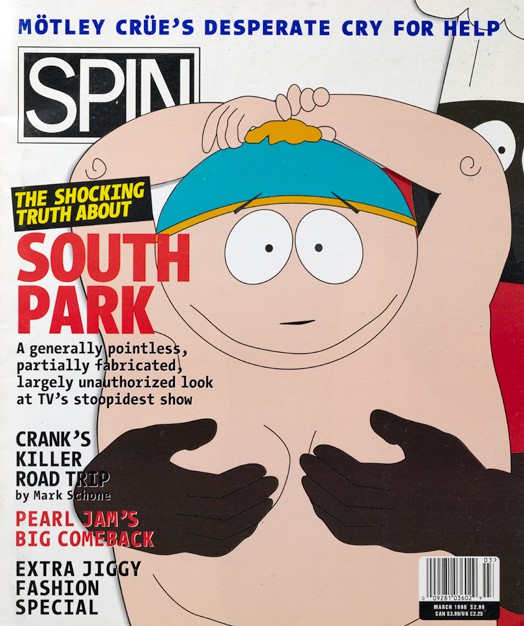

This piece originally appeared in SPIN’s March 1998 issue. In honor of the 20th anniversary of South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut, we’re republishing it here.

Here’s how it works in the post-Simpsons era. The tremors start at coffee shops, movie queues, dorm rooms: young people talking in bizarre pinched voices. Goateed cashiers spouting off-color catchphrases. Strange little icons on T-shirts and screen savers. Then, the websites spring up. The upstart network flourishes. The single is released. The movie is announced. Suddenly, before you know it, were up to our bungholes in ’90s cartoon Zeitgeist.

With the unstoppable force of a dead—Chris Farley joke, Comedy Central’s sick, crudely animated half-hour show South Park—featuring the adventures of four gimlet-eyed. foul-mouthed third-graders—has become not just the hottest cartoon but the hottest youth-cult phenomenon in the country.

Like Bart and Butt-head before them, the construction-paper-hewn Stan Marsh, Kyle Broslofskyi, Eric Gartman, and the permanently hooded Kenny McCormic now rule the malls of America. Their likenesses are everywhere, including on last year’s hottest-selling T-shirt (“We have merchandisers lined up around the block!” boasts Comedy Central spokesman Tony Fox). Their signature lines—”Kick ass!” “Omigod, they killed Kenny”—are on the lips of paperboys and grad stu-dents across the nation. They’ve even impressed the critics. Next to “such popular agents of murder and mayhem” as South Park‘s “cackling characters,” observes the New York Times’s Michiko Kakutani, “the Devil doesn’t even stick out.”

Industry seismologists measure fan ardor more directly. “CNN has to have a worldwide disaster to come up with a 1.4 [rating],” said one television industry consultant. For its Christmas show, South Park earned itself a 5.4 rating, the highest for an original series in Comedy Central’s history; 4.5 million people tuned in, more than seven times Comedy Central’s average. Rights to a South Park soundtrack album, currently in the works, have a rumored price of $2 million. Meanwhile, showbiz giants from Jay Leno to Jason Priestley to George Clooney have either offered or given the show subliminal voice cameos—the last performing the woofs of a gay dog.

All of this—plus a feature-length film and the inevitable consumer effluvia (mugs, boxer shorts, beach towels, backpacks)—comes on the strength of just a handful of episodes. Gen-X college roommates Trey Parker and Matt Stone hit the motherlode of goofball hip with one alarmingly simple idea: Take a bunch of cute li’l quaintly animated characters—redolent of early-’70s instructional films and Peanuts holiday specials—and slam them into ’90s grossness and dread.

Somehow, by featuring vomiting, farting, racial slurs, and decapitations, their not particularly high-minded creative enterprise seized pole position in the culture industry. Somehow, South Park must speak to some hunger deep within us, must reaffirm some basic truths about humanity. That, or we’re truly a nation of retards.

“There is no more direct and accurate way of finding out what is really on a people’s collective mind,” writes Alan Dundes in his book Cracking Jokes, “than by paying attention to precisely what is making the people laugh.” To that end we turn to 1996’s “The Spirit of Christmas,” the $750 video hallmark that launched South Park.

In “Christmas,” Parker and Stone introduced the four snowsuited characters and their perpetually wintry milieu, had them quarrel and bait the Jewish Kyle and hurl fat jokes at the rotund Cartman, and brought in the off-color surrealism that would become a South Park trademark. In flowing robes, Jesus appears before the kids saying he has arrived to avenge the despoiling of his name by Santa Claus. (“Don’t say ‘pigfucker’ in front of Jesus,” Stan admonishes Cartman.) Jesus begins a Mortal Kombat-style kung-fu duel with his arch-nemesis “Kringle” while the kids fret over whom to root for. All the elements were in place: sadism, sacrilege, and nonstop profanity.

After the furiously circulated video led to a deal with Comedy Central, South Park debuted to flesh out the four kids’ world. Early episodes introduced us to the priapic school Chef (voiced by Isaac Hayes), the schoolteacher Mr. Garrison and his hand-puppet/id Mr. Hat, Wendy Testaburger (whose presence makes the love-struck Stan vomit), and other town folk. As in “The Spirit of Christmas,” all the characters remained jittery composites of cut-up paper shapes whose eyes blinked and teeth gnashed in distant approximations of facial expressions.

With a built-in audience of the tens of thousands who had seen the Xmas bootleg, South Park was an instant hit—especially among snickering white pubescents. Elektra Records’ Brian Cohen, responsible for purchasing TV commercial time for the label, knew the show was made-to-order for advertising the likes of Pantera, Metallica, and AC/DC. “You go to the concerts and you see a lot of young boys who are ready to, you know, cut something and make it bleed,” he says. “It was pretty clear that this was the right audience.”

But while the show works brilliantly as a cult hit, it makes a curious transfer to the larger culture. Unlike comic sensations of yore—Monty Python, say, or Firesign Theater—you don’t sound like a soigné aficionado of fine comedy when you repeat South Park sound bites at school: You sound Special Ed.

And while there is enough splenetic wit and manic detail to generate obsessive fandom (entire sections of websites are dedicated to deciphering just what Kenny is mumbling), subjects like alien abduction, genetic engineering, and Kathie Lee are hardly original targets for satire. South Park fares well in comparison to Beavis and Butt-head, but not to its other obvious forebear, The Simpsons.

A years-old institution with a full team of writers, The Simpsons is both higher-yield jokewise and more virtuosic, with gags compounding gags and a more coherent sense of the characters’ foibles and predilections. The Simpsons and its follow-on King of the Hill also undertake a broader critique of suburbia, mass media, family life, and beer-swilling fat guys than does South Park. South Park‘s more about puking and aliens and stuff.

In a sense, though, that’s the point. South Park is a punk-rock Simpsons: not as droll nor as well-executed. but faster, cruder, with fewer characters and less ambition. Not only is there a firm grasp of early punk’s nihilistic juvenilia—Cartman’s Hitler Halloween costume was positively Ramonesian in its gleeful bad taste—but South Park also shares punk’s slapdash production values. Turnaround time per episode is lightning-fast—once every three weeks—which makes it the most shoot-from-the-hip comedy program on television.

Like many subcultural crazes, the show’s appeal is about style and form more than content. Cartman’s voice—a trebly, gravelly mix of Truman Capote and Wolfman Jack—is alone worth the price of basic cable. And, at its most elemental, South Park is founded on a sight gag with legs. Of the evergreen comic tropes out there—men in dresses, talking computers, vice presidents—one of the most dependable is the dismembering of cute little moppets. (Witness Saturday Night Live‘s immensely popular “Mr. Bill” series.)

The central irony is that, for all its absurdity, South Park is probably truer to the kid experience than any other program on TV. It has the familiar sadism, the shameless greed, and the exuberant curiosity—in spades. Perversely, South Park may be one of realest social worlds on TV.

But much like childhood itself, South Park isn’t a franchise that’s built to last. Even by the sixth episode, “Death,” Parker and Stone were already making none-too-subtle allusions to crass TV shows “that have come and gone that have been very bad [and usually] get taken right off the air.” Maybe, as the creators themselves seem to recognize, this wouldn’t be such a terrible thing.

Will South Park linger ignobly like Roseanne and the Rolling Stones, cashing checks while tarnishing its luster? Or will it—as the recent sub-sub-lowbrow Christmas episode suggests—go out in a blaze of talking poo? South Park‘s essential comedic device—the clash between childhood innocence and adult puerility—is otherwise known as “junior high,” and everyone graduates sooner or later.

With a new movie beckoning and their place in history secured, Parker and Stone may just be savvy enough to sabotage their creation before it turns against them. Even Cartman knows it’s better to gross out than fade away.