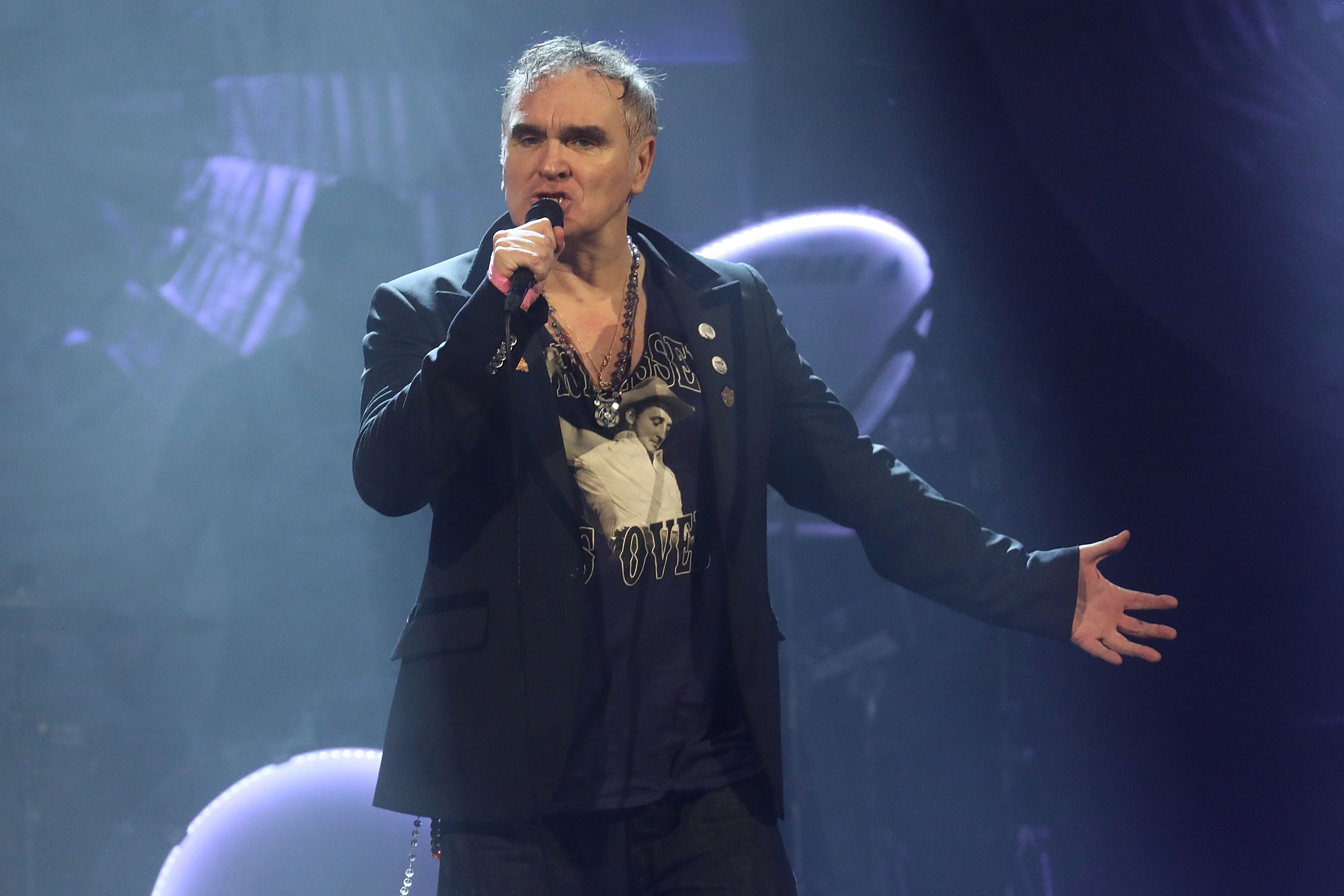

For the last 10 months or so, Nick Cave has written often to fans via his website and newsletter Red Hand Files, thoughtfully and eruditely answering their questions about grief, politics, music-making, religion, and so on. The latest entry is a response to a fan who asked for Cave’s take on Morrissey’s recent vocal support for reactionary anti-immigrant politicians in the U.K. and assertion that “everyone ultimately prefers their own race.”

“Generally, is it possible to separate the latter-day artist from his earlier art?” the fan wondered. “More specifically, what are your views on Morrissey, both early days and his newer more ugly persona?”

Cave’s response amounts to a recognition that artists no longer maintain dominion over their work once they’ve shared it with the world. It’s clear that he feels a deep connection to Morrissey’s work: He calls the former Smiths frontman “arguably the greatest lyricist of his generation,” and his songs “works of unparalleled beauty.”

It’s equally clear that Cave is repulsed by Morrissey’s embrace of the far-right, which he calls a “dangerous and repressive belief [system].” In Cave’s view, the latter aspect does not negate the former, because Morrissey does not and cannot control the relationship that listeners form with the songs he composes. Cave writes in part:

I think perhaps it would be helpful to you if you saw the proprietorship of a song in a different way. Personally, when I write a song and release it to the public, I feel it stops being my song. It has been offered up to my audience and they, if they care to, take possession of that song and become its custodian. The integrity of the song now rests not with the artist, but with the listener.

When I listen to a beloved song – Neil Young’s ‘On the Beach’, for instance – I feel, at my very core, that that song is speaking to me and to me alone, that I have taken possession of that song exclusively. I feel, beyond all rationality, that the song has been written with me in mind and, as it weaves itself into the fabric of my life, I become its steward, understanding it better than anybody else ever could. I think we all can relate to this feeling of owning a song. This is the singular beauty of music.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter what Neil Young’s personal conduct may be like therefore, or Morrissey’s, as they have handed over ownership of the songs to their audience. Their views and behaviour are separate issues – Morrissey’s political opinion becomes irrelevant. Whatever inanities he may postulate, we cannot overlook the fact that he has written a vast and extraordinary catalogue, which has enhanced the lives of his many fans beyond recognition. This is no small thing. He has created original and distinctive works of unparalleled beauty, that will long outlast his offending political alliances.

Cave’s answer does not address the material realities of this dynamic: Does one continue buying Morrissey concert tickets, or streaming his music, knowing that the money you’re giving enables him on some level to remain in the public eye, spewing hatred? But it does offer empathy to the predicament of the Smiths fan, without sacrificing moral clarity: If you grew up with the Smiths, Morrissey’s songs probably mean a great deal to you, and you’re not a bad person for still finding them moving.

Cave’s response also leaves ample room to disagree; in fact, for him, the freedom to disagree in public is central to the question itself: “Perhaps it is better to simply let Morrissey have his views, challenge them when and wherever possible, but allow his music to live on, bearing in mind we are all conflicted individuals – messy, flawed and prone to lunacies.”

Read the whole thing here.