This story originally appeared in the June 2005 issue of Spin. To celebrate the 15th anniversary of the band’s sophomore album Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge, we’re republishing it here.

Eight or nine years ago, mild-mannered comic-shop clerk Gerard Way couldn’t tell you much about rock’n’roll. Deathly pale, introverted, and adrift in the working-class suburb of Belleville, New Jersey (about ten miles west of Manhattan), he could, however, speak at length about role-playing games, horror flicks, and numbing monotony. Oh, and superheroes, of course. You see, Way has always known that the most essential element of any good superhero is a killer origin story.

Though not quite as cinematic as getting bitten by a radioactive spider, the transformation of Gerard Way, 28, into a snarling, self-proclaimed rock’n’roll savior is still remarkable. Like many life-changing stories of the 21st century, it all began on September 11, 2011. On that clear-blue-sky day, Way—who had graduated from New York’s School of Visual Arts to a sunlight-free existence drawing in his mom’s basement—was coming into Manhattan, unaware of the tragedy. “Something just clicked in my head that morning,” he says. “I literally said to myself, ‘Fuck art. I’ve gotta get out of the basement. I’ve gotta see the world. I’ve gotta make a difference!'”

Inspire by the uplifting screamo anthems of fellow Garden Staters Thursday, Way had been playing guitar and trying to write songs in his room; he had dreams of starting a band named My Chemical Romance (after Irvine Welsh’s book Ecstasy: Three Tales of Chemical Romance). But unlike Thursday’s Geoff Rickly—who would help sign My Chem to indie label Eyeball Records—Way had no desire to sing about his mundane circumstances or surroundings. He wanted to inspire a movement and recast his fortress of solitude as a teeming, limitless Metropolis. His songs wrapped the anthemic community spirit of emo in the personal mythology of ’70s art rock and ’90s Britpop. The world may have seen Way as a shy, failed comic artist, but in his head and in his songs, he was a vampire, a death-dealing badass, a lover, a fighter. He was a superhero. All he needed was a superteam.

He recruited guitarist Ray Toro, 27, a film student from the neighborhood who grew up performing Joe Satriani and Led Zeppelin riffs on nights when his mother wouldn’t let him out of the house. Then came Way’s younger brother, Mikey, 24, a waifs Anglophile rock scenester and part-time college student who worked in a bookstore and could barely play his bass. Guitarist Frank Iero, 23, a tattooed punk who had suffered through a sickly childhood, was adopted by My Chem after his own group, Pencey Prep, dissolved. And last year, drummer Bob Bryar, a former soundman for the Used, joined after the band parted ways with original member Matt Pelissier.

On paper no one would mistake these motley Jersey kids with thick accents and scattered interests for rock stars—and no one would ever confuse them with sexy X-Men-like world conquerors, either. They flailed at the beginning. For their very first show, Gerard lathered his face with greasepaint and screamed curses at the crowd, Mikey drank heavily to mask his stage fright, and Toro soloed like he was in a Metallica tribute act. But Gerard saw potential—after all, his favorite comic-book team had always been the Doom Patrol, those bickering, suicidial misfits who succeeded despite being shunned by the outside world.

“We always had vision, but we weren’t sure if it would translate or just come off as pretentious,” says Mikey. “We were playing basements, and Gerard would be like straight-up Ziggy Stardust. Kids would be horrified.”

“Labels would come to see us because of the whole emo thing,” says Gerard. “But no one believed we came from Jersey. They’d say, ‘You’re so different, so extroverted…It doesn’t make any sense!'”

My Chem’s melodramatic live shows and their 2002 debut album, the darker-than-noir I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love, earned them a devoted fan base of Hot Topic girls, self-loathing goths, E-eating Britpoppers, and more than a few hardcore hulks who hid their copy of Bullets with their secret stash of Morrissey imports. It also earned them a lucrative contract with Warner Bros., which won a tough bidding war with DreamWorks. The story easily could have stopped there: Most groups hyped in anticipation of the emo boom that never quite happened have been relegated to the clearance racks, or worse, Warped Tour’s second stage. But last year’s Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge shattered everyone’s expectations. Featuring Gerard’s original illustrations, the album—conceived as a road-trip horror screenplay about a vengeful lover’s quest for 1,000 innocent souls—was brash and squishy, ostentatious and moving. The lead single, “I’m Not Okay (I Promise),” shotgun-married self-lacerating lyrics and a squealing Queen-style guitar solo. Other songs dabbled in homoerotic vaudeville (“You Know What They Do to Guys Like Us in Prison”) and explosive punk pop (“Cemetery Drive”), and there were even three lighter-worthy power ballads. Fueled by the brilliant Quadrophenia meets Rushmore video for “I’m Not Okay,” the album has at press time sold more than 500,000 copies.

“A kid watching Thursday is going, ‘They are empowering because that could be me up there—Geoff is singing what I want to be singing,'” says Gerard. “With us, it’s like, ‘These guys are so fucking crazy I need them in my life.'” Or, to put it bluntly, introverts inspire others to form bands; extroverts sell records.

“I told them after their first record they were gonna be much bigger than Thursday,” says Rickly. “We’re flipping sides of a coin. He deals in the surreal and make-believe and is able to project a confidence that I can’t. He has this other place where he can hide and control things. Gerard’s always telling me that he’s my villain. But I think he’s an antihero.”

* * *

When I meet up with the band in snow-covered Niagara, New York, on a dreary Tuesday in March, the line for tonight’s show—a $2 Bill MTV2 taping with coheadliners the Used—is three blocks long and almost none of the diehards have bothered with coats. Gerard, who is surprisingly small and, well, ordinary looking in person, is onstage finishing up a sound check. In a different context, he could be just another Anykid from Anytown, USA, with his sallow complexion, stringy hair, fingers lashed with paper cuts from comics, and nails bitten to the nub. But here, amid the instruments and equipment, he’s completely in command, cracking wise with the crew and smirking off what looks like a rather large amount of blood from his mouth. When I ask him if he’s all right, he grins. “It’s just makeup, man. I’m doing great!”

This, unfortunately, has not been the case until very recently. During 2004, as the band’s success increased exponentially, Gerard was, as he himself sang, “not O-fucking-K.” But no superhero worth his legend is infallible. “Growing up, I always wanted to be Batman,” he says, taking a drag on his umpteenth cigarette of the morning, “because he was just a normal dude. Superman was all-perfect and had a duty to protect people. For Batman, it was a compulsion, like a religious thing. All the best heroes are ordinary people who make themselves extraordinary.”

For Gerard, the distance between his real life and the demon he became onstage grew wider by the day. “I was so scared of performing that I had worked out the exact chemical combination to get me functioning in the band,” he remembers. “I would drink from when I woke up until set time. I lived, breathed, and shit for the show. I wore my stage clothes—the leather jacket, the boots—all the time. As bad as they smelled, even when they were falling apart, I wouldn’t take the costume off. I had no separation in my head.” He lets loose a fierce smoker’s cough and smiles ruefully. “It got so bad that I started to refer to him as Gerard. I actually started becoming someone else entirely.”

The drinking, though extreme, was nothing new to the Way brothers, who say alcoholism runs in their family. “Where we’re from, a suburb of a city, there’s nothing to do but drink, fight, and fuck,” says Gerard. “It’s very easy to get caught in this fucking working-class, punch-the-clock, get bombed, and try-to-find-someone-to-poke lifestyle.”

It was the November 2003 passing of the Ways’ grandmother (the inspiration for Three Cheers‘ best song, “Helena”) that pushed Gerard to a more dangerous form of escape. “I couldn’t deal with her death,” he says, “and I took my first Xanax. After that, it snowballed. I would get wasted for a show, then need to shut my brain off at night—because my brain is always moving a million miles a minute. The pills allowed me to relax and sleep. But then cocaine came into play, and everything went out of whack.”

Gerard’s divorced parents—mom’s a hairdresser, dad an auto mechanic—were flummoxed by their quiet son’s public meltdowns. They called Mikey frequently, but the younger Way felt he was in no place to lecture his older brother on sobriety. “we’ve shared a lot of the same troubles,” he says. “But sometimes he’s the older brother and sometimes I have to be.” Things got particularly ugly during a gig in Kentucky last summer, where a hammered Gerard wandered under the stage and tried to sabotage his bandmates by refusing to sing or even emerge from his hiding place for the rest of the night.

“After that show, I wanted to put down my guitar and leave,” says Iero. “And I’ve never felt that way about playing.” A day or two later, Gerard celebrated a Killers concert in Kansas City by snorting an eight ball of coke and vomiting in the street. His predawn crash left him sobbing in his tour-bus bunk, racked by suicidal thoughts. But a three-hour talk with band manager/official best friend Brian Schechter convinced Way that he needed to get clean.

But first there was a tour of Japan: After playing the Summer Sonic festival in Osaka before a crowd of 10,000—My Chem’s largest ever audience—Gerard puked sake, beer, and God knows what else into a trash can for 45 minutes. Then, with vomit still on his shirt, he told his bandmates that he had swallowed his last drink. The night after they landed back in Jersey, Gerard was in AA. And with a willpower even Bruce Wayne would admire, he has been clean—of everything except his beloved cigarettes and coffee—ever since.

“I never expected it to be that easy or cut-and-dry,” says Iero with real respect in his voice. “I mean, it was Gerard—we would have given him a million chances. But he’s very strong. He’s never slipped up. He tried to take Nyquil once, and I smacked him.”

“I was terrified to be sober onstage for an entire tour,” Gerard says. “I felt like Spiderman without the mask. But now I feel more dangerous and sharp than ever. I’ve got a memory again, and I’ve got a future. I feel like we’re undefeatable. We go onstage now, and we feel like we’re the greatest band in the world. Like we’ve got the whole world by the balls!”

* * *

Traveling on the bus with My Chemical Romance is a new masterclass in the band’s evolution over the past few years. On the 12-hour ride from Niagara to Maine, only one beer is sipped (and eventually bricked by Iero), while Diet Cokes are consumed like illicit substances. The band and crew have been kitted out with brand-new T-Mobile Sidekicks and Nintendo DSs, which they fiddle with constantly, rarely making conversation. The biggest controversies are over who keeps leaving empty cups in the common area and whether anyone has “accidentally” used Iero’s strictly vegetarian George Foreman grill to heat up hot dogs. The guys content to treat every aspect of life on the road—from meet-and-greets to border crossings to who gets to watch whose porn in their bunks—with a pleasant professionalism.

“We all have very humble backgrounds and very geeky interests,” Mikey says with a shrug. “On the tour bus, when most bands would be defiling a young lady or doing massive amounts of cocaine, we’re swapping copies of New Avengers.” He’s even trying to join his brother in giving up drinking. “It’s counterproductive,” he says. “I don’t like waking up and playing catch-up to my day.”

Noticeably absent from this scene is Bert McCracken, frontman of the Used. When I spent time with My Chem in early 2003—while writing a story on the Used—McCracken and Gerard were well on their way to forming a toxic partnership. The two quickly bonded over music and a lust for the rock’n’roll life. After one Chicago show, they drained a hotel minibar, smoked pack after pack of cigarettes, and annihilated themselves to the point where both missed sound check the next day. Later, Gerard told me that night was partly the inspiration for “You Know What They Do to Guys Like Us in Prison.”

“Bert was like a tour guide for me,” says Gerard now. “he was a star, and I was just a weird little dude who he believed in. Our relationship blossomed by being bad together, but ultimately, I think, we want different things.” McCracken, who has struggled with addiction in the past and is not currently sober, did not want to be interviewed for this story. Still, he and Gerard occasionally perform a version of David Bowie and Freddie Mercury‘s “Under Pressure” duet as an encore to the Used’s set.

Way’s ability to clean up his act is a large part of why his band may one day surpass all his mentors in popularity. “My Chem is accessible enough for kids to get it but different enough to still freak their parents out,” says Good Charlotte‘s Joel Madden. “Plus, once on the Warped Tour, Mikey gave me a Diet Coke from his stash—that’s like cigarettes in prison. They rule so much I’m even planning on getting into some D&D [Dungeons & Dragons] with Gerard.”

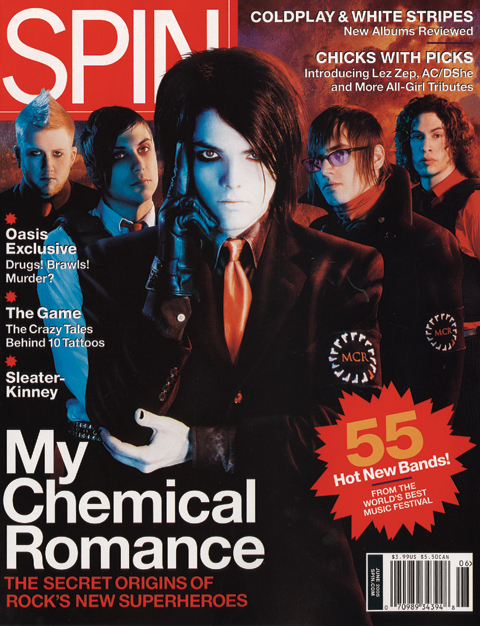

My Chemical Romance live is now a taut production. Inspired by their flamboyant frontman, Iero and Toro take the stage in matching bulletproof vests and eye shadow, while all five members sport MCR wristbands and vaguely SS-style suits in the official team colors of black and red. In Portland, Main, the audience—dulled senseless by four pro forma opening acts—springs to vibrant, circle-moshing life when My Chem take the stage. Gerard, his leather now replaced with a suit jacket, conducts his band’s songs like a demonic four-star general. He howls and roars, begs the crowd to spit on him, and leads an arenawide middle-finger salute. Though he has a girlfriend whom he plans on moving in with as soon as this touring cycle ends, he has Frenched-kissed McCracken onstage and begs mosh-pit mooks to fuck him.

“It’s extremely important for these kids to realize that they can do and be whatever they want,” Gerard says. “Warped Tour was big for that. Instead of drinking a bunch of beer and calling a kid a faggot because he’s smaller than you and wearing black, why don’t we just have a good time? And big jar-headed dudes got that. To be able to break through those layers of muscle and get to their hearts was one of the biggest victories this band has ever had. We go onstage every night and look like the most dangerous cupcakes in the world, and that’s another victory—because these kids aren’t booing us or calling us fags. They’re saying, ‘Fucking go for it!'”

The wider world is noticing My Chem’s breakthroughs. Green Day recently chose them to open the next leg of their triumphant comeback tour, and they’re also set to headline Warped. MTV has been an ardent supporter (the band has even appeared on teen showcase TRL), thanks to their dazzling videos (Marc Webb’s clips for “Helena” features a funeral set in a cathedral, where a corpse breaks into a Busby Berkeley-style dance routine). “They’re showmen who take real chances in their music and their visuals,” says Alex Coletti, director and executive producer of the $2 Bill show. “And the record is a monster—there’s a brash snottiness to it that reminds me of Guns N’ Roses.”

Still, no matter how professional and focused the band has become, offstage Gerard can seem like a kid who is still in search of himself. Around hour four of the trek to Maine, he’s paddling around the bus in black union-suit pajamas with a skeleton pained on the front that he bought in Japan. It’s predawn and the snow is falling as well pull into a creepy run-down truck stop—a scene straight out of one of Gerard’s beloved cheese-ball horror flicks. While the rest of the band sleep, Gerard claims from his bunk and heads straight toward a notebook to scribble some insomnia-inspired lyrics.

As the bus refuels, Gerard walks out into the slush, dressed as a skeleton, his hair streaked and filthy, desperate for a smoke, freaking out truckers and talking about what’s coming next. “I’m clearheaded enough to live through the next adventure,” he says. “I’m awake for it, and I feel as if I have something to say, to write something right from my soul into the audience’s bloodstream.”

He slips a little and shivers in the cold. “It feels like I’ve been unmasked, and I don’t know which version of me is the character anymore. Like those lyrics I just wrote are the most unsubtle, obvious romantic words I’ve ever written.” Then his face darkens and he cackles. “Maybe I’ll go back in there and add a line about stabbing my eyes out with scissors just to keep them guessing!”