In addition to being one of hip hop’s most influential sample-based producers, Madlib is also among the genre’s most dedicated archivists. There’s a history lesson in the delicate patchwork of his production, with beats that move seamlessly between past and present, incorporating a staggeringly diverse collage of samples. A track that begins in the realm of obscure ’70s soul might explode into contemporary Afrobeat; Sun Ra’s ecstatic Afrofuturism might recede into the tumbling, hypnagogic runs of Bill Evans, or spring forward into a slick Daedelus instrumental. Madlib thrives in these intertextual spaces, and in the deconstruction and reassembly of entire musical histories. Clipping and pasting across genres, eras, and emotional registers, his hunt for obscure snippets is as much about preservation as the construction of something new. Whether crammed into small corners, superimposed over an entire verse, or left to languish in a slow fade, the ghosts of Madlib’s crackling records evoke the past, while the beats that contextualize them insist on the now.

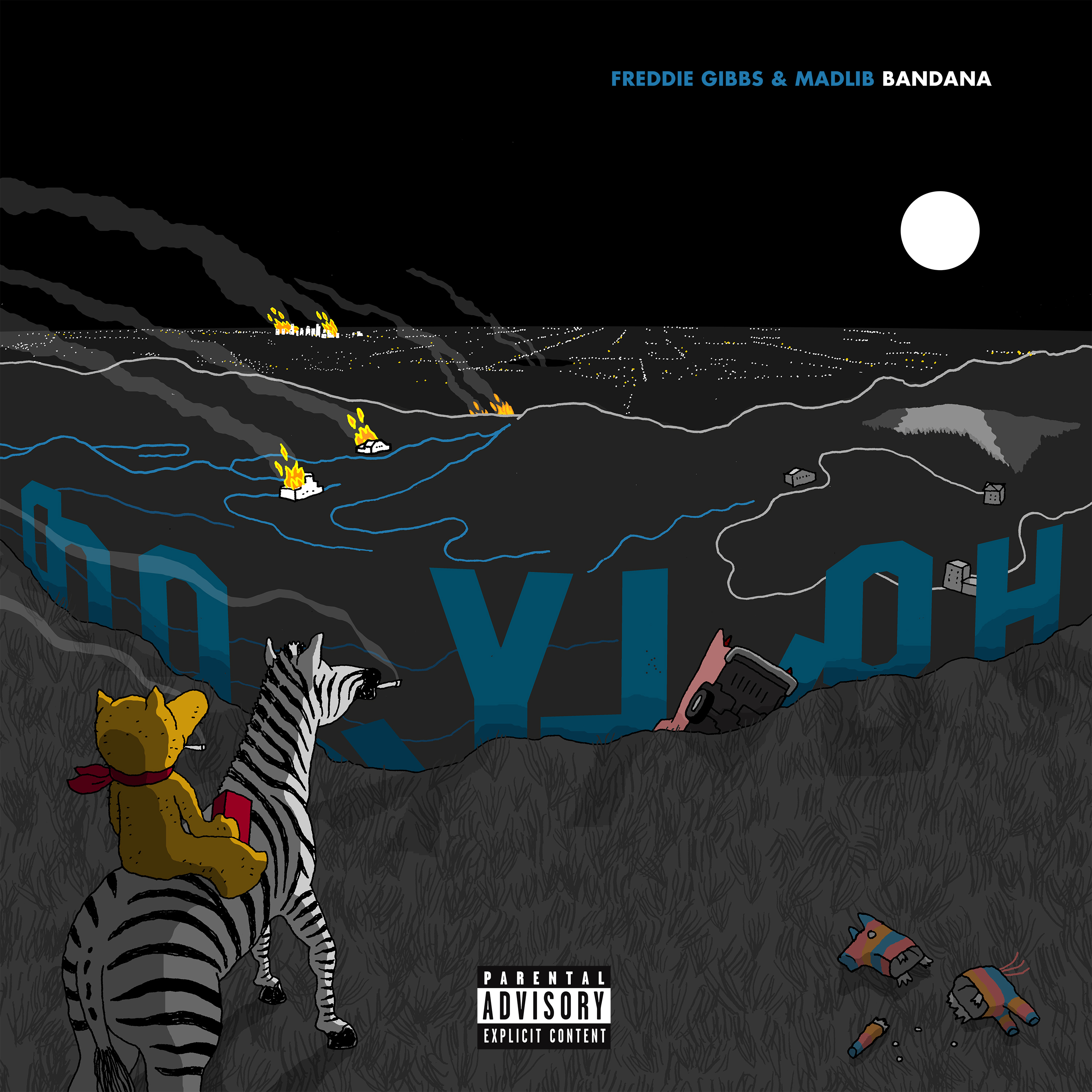

Freddie Gibbs, like MF DOOM before him, is the rare MC who can ground Madlib’s time-traveling sound collage, with an audacious technical ability and musical knowledge to match the producer’s. Gibbs first prostrated himself at the temple of Lord Quas on 2014’s Piñata, a dramatic collision of gangsta rap and crate-digging eclecticism. The strength of the collaboration was in that contrast — between vertiginous, disorienting production and the unwavering steadiness of Gibbs’ writing. Gibbs cut through the sudden beat switches and frenetic Danny Brown cameo appearances with verses that, like Madlib’s instrumentals, tied present to past, examining both his crack-dealing roots and his aspirations to hip hop dominance. Bandana, their second collaborative album, isn’t a sequel so much as another helping of what worked so well the first time: a selection of Madlib’s finest beats, cave-aged and peppered with the same Gibbsian blend of lighthearted flexing and street philosophy. It’s a more refined take on a proven formula, with sterling track after sterling track cementing Gibbs and Madlib as a remarkably effective duo.

Without a single unifying concept, Bandana’s focus is on the bond between Gibbs and Madlib, which, two albums in, now seems to verge on the psychic. Gibbs had heard most of Madlib’s Bandana beats before he was thrown in jail for sexual assault charges in August of 2016. When he was acquitted in September, he’d already written most of the album’s lyrics. “I had no music player or anything like that in my cell, so all I had was memory,” Gibbs told Billboard. “I’d think about the subject matter, and all night I just played the beats in my brain.” “Crime Pays” is a prime example of the two men’s unlikely chemistry. Looped licks from a glossy electric keyboard help dictate Gibbs’ segmented staccato flow, and he ends each bar with an emphatic rhythmic gut punch: “Diamonds in my chain, yeah I slang, but I’m still a slave / Twisted in the system, just a number listed on a page.” On “Massage Seats,” Gibbs is unfazed by a barrage of jagged vocal samples, maneuvering in and around Madlib’s syncopated percussion track with the dexterity of a jazz musician.

Through it all, Gibbs sounds hungry as ever, even as he cements his role as one of hip hop’s most proficient and consistent MCs. He’s 37 now, and a father. Life lessons learned on mixtapes like The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs and Baby Face Killa have had time to set in; he still raps about old habits, but with newfound wisdom. On “Giannis,” Gibbs reflects on that juxtaposition in the context of family life: “Every mornin’ I wake up with my daughter, Dora Explorer / Then I get right back to the pot / Kitchen stankin’, that’s potty trainin’ / Murder note go to the muhfuckin’ plaintiff at my arraignment.” The sun-warmed guitars of “Cataracts” lend a poignancy to Gibbs’ lyrics, like sepia in an old photograph. “Knew the Lord was in the room when my daughter took her first breath / Cold turkey on the dope, had to gain a knowledge of self,” he rhymes. And it’s the same story on “Practice,” with Gibbs’ girlfriend insisting that he come home with his daughter (“nothin’ more important than your baby”). In “Soul Right”—a highlight on an album full of highlights—Gibbs waxes poetic about “way back” when every day he’d “fuck up a bulletproof glass chicken plate.” On Piñata, Gibbs documented his long-running love affair with Harold’s Chicken Shack down to his exact order (“six-wing, mild sauce”); now, he’s looking back on youth at a remove. A dual sense of wisdom and perspective makes Bandana a more mature statement than its predecessor.

It’s also a more cohesive record than Piñata. Ultimately, the fact that Gibbs and Madlib’s first album-length collaboration featured “all the mother fuckers in the rap game worth fucking with,” according to a sticker on the physical edition, was to its detriment (see: Ab-Soul on “Lakers”). Bandana’s few guest spots serve as punctuation, rather than gratuitous embellishment. Pusha T’s verse on “Palmolive” is mostly recycled from “Nosetalgia,” but it works, and his signature snarl brings a welcome edge to the protracted howl of a beat. On “Education,” it’s exciting to hear old school veterans Yasiin Bey and Black Thought rapping over a genuinely adventurous instrumental again. Bey is typically contemplative: “A dead end street with a lemonade stand / Where is the sky in upside-down land? / That question is hard if you can’t see the stars / I’m really not sure — ask me tomorrow.” Black Thought comes through with all the furious energy of his freestyles: “The system we compete against, it’s farm-to-table, hand-picking them ingredients, civil disobedience, encyclopedia definition of greediness.” Everyone’s on their best behavior, and Gibbs always proves he’s more than capable of keeping up.

Bandana is the coming-together of two radically different artists, bonded by a shared respect for music, for history, and for memory; old samples meet modern production, and today’s father confronts yesterday’s gangster. In connecting to each other, they tap into a broader cultural lineage. Gibbs and Madlib pay respect to their forbears by grappling with personal, political, and artistic histories in music that’s distinctly of the moment. It’s palpable on “Flat Tummy Tea,” in Gibbs’ lyrics about contemporary depictions of slavery: “Slave movies every year, yeah, the master gon’ remind us / If we don’t take it, we don’t deserve it back / And 6000 years done ran up, the kings of the earth is back.” There’s frustration here, bluntly articulated, but there’s also something galvanizing and communal about that anger. Gibbs and Madlib look back in order to move forward—blending past and present on the canvas, they arrive at something altogether timeless.