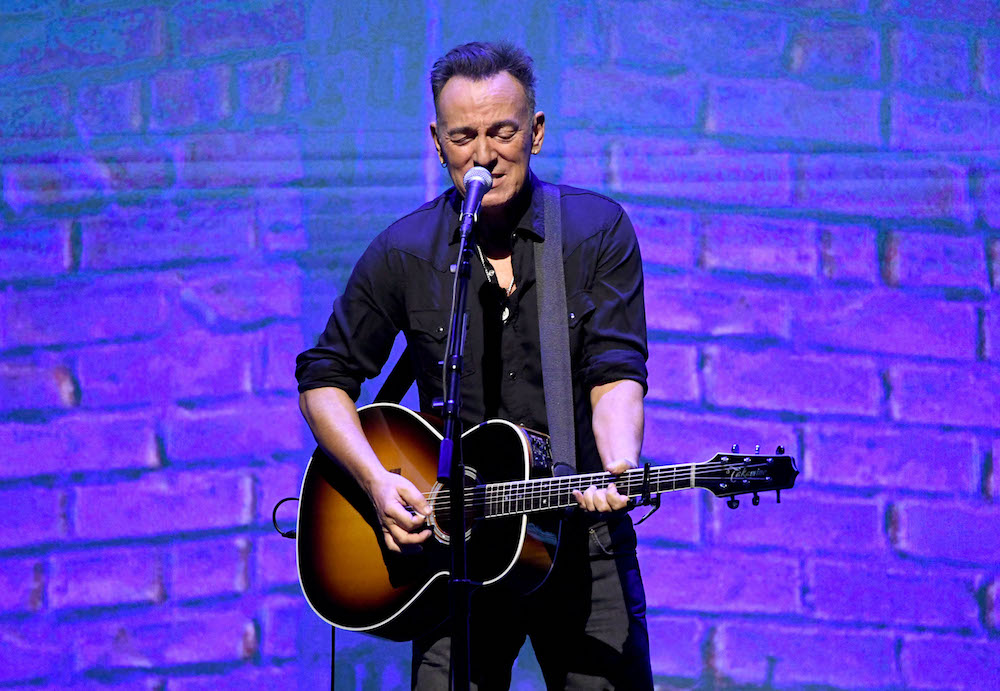

Years before Bruce Springsteen delivered Western Stars in June 2019, rumors circulated that the Boss was working on a record that would swap rock’n’roll for orchestral pop. Springsteen himself mentioned the album in a 2016 Vanity Fair profile, claiming he completed “a solo record, more of a singer-songwriter record” after a period where he was obsessed with “pop records with a lot of strings and instrumentation.” In particular, he mentioned the classic string of hits that Jimmy Webb penned for Glen Campbell: “Wichita Lineman,” “Galveston,” “By the Time I Get To Phoenix,” all sumptuous singles evoking the hazy twilight of the hippie era.

Western Stars does indeed wear its Webb influence proudly, using that transportive symphonic sway to summon a sense of majestic melancholy similar to Campbell’s foundational hits. The album’s subject matter will not be unfamiliar to Springsteen listeners, telling tales of heartbroken wanderers who search for a better place or a person to make them feel at ease. The cinematic vistas of the music may be more surprising at first, but a close listen Western Stars, and to Springsteen’s back catalog, reveals that he’s been working toward this spacious sound for a long time.

At the dawn of the 1980s, Springsteen started to sharpen his songwriting, gradually pulling back from the open-hearted epics that defined the rampaging sound of the E-Street Band through the 1970s. As his songs got tighter, he honed his productions so they were simultaneously expansive and precise: The River sounded like a hyper-charged radio station, while Nebraska was spare and dusty as old Woody Guthrie LPs. In many ways, Western Stars represents the culmination and merging of these two extremes and themes; between the early ’80s and 2019, there were many times that Springsteen hinted at its blend of bruised character sketches and lush sonics. These songs, stretched out over the decades, represent the road Bruce took to reach Western Stars.

“I’m on Fire” (Born in the U.S.A., 1984)

Also Read

SAME AS THE OLD BOSS

The fourth of six Top Ten singles from Born In The U.S.A., “I’m On Fire” stands apart from the rest of its accompanying record. It doesn’t swing for the bleachers, but smolders and seduces. Underneath that slow burn lies a lonely heart: there’s no indication that the object of the narrator’s affection returns his desire. That isolation can also be heard throughout Western Stars, but the strongest connective tissue between that 2019 album and this 1984 hit is execution. “I’m On Fire” contains no excess fat, not a wasted line or note, an aesthetic that underpins Western Stars, even if its arrangements are decidedly grander.

“Cautious Man” (Tunnel of Love, 1987)

“Cautious Man” is spartan and ghostly, telling the tale of Bill Horton, a man who lets his restless heart get the better of him when he’s faced with an otherwise happy marriage. Though Horton winds up returning home in this 1987 song, his wanderlust makes him a precursor to the wounded souls on Western Stars, who seek salvation by roaming the road. “Cautious Man” has an additional connection to the California landscapes of the new album: Horton wears “love” and “fear” tattoos on his hands, a clear allusion to the tattoos Robert Mitchum’s evil preacher bears in Charles Laughton’s classic 1955 noir thriller The Night of the Hunter.

“Two Faces” (Tunnel of Love, 1987)

“Two Faces” may play as a little more purely country than the songs that populate Western Stars, but that only underscores the Glen Campbell affinity that drives the new album. With its keening melody and lyrics of inner torment, it’s reminiscent of some of the Campbell hits that weren’t written by Webb: songs that walked a straighter line, yet still were heavy with melancholy portent. Once again, Springsteen’s hushed but anguished anxiety drives the track, a sense of unrest that telegraphs the emotions later heard on Western Stars.

“My Lover Man” (Tracks, 1990 outtake)

From the start of his career, Bruce Springsteen specialized in character songs, but “My Lover Man” is something different: a song written from the perspective of a woman. This makes this outtake—recorded in 1990 and released originally on the 1998 box set Tracks-–play as something of an answer to all the Springsteen songs about wandering men, a subgenre that extends all the way to Western Stars. Within a country-pop arrangement that echoes Tunnel Of Love, there are hints of the grand orchestral sweep Bruce would later attempt: as the synths start to cascade, they sound like strings in waiting.

“Happy” (Tracks, 1992 outtake)

An outtake from 1992, the year Bruce Springsteen released not one but two albums, “Happy” is a slow-burning ballad. Although there is some darkness dancing in the margins of the lyric, “Happy” is at its core a song where the narrator finds comfort in a lover’s arms. This makes it more romantic than much of what shows up on Western Stars, yet its stately classicalism seems to cry out for a majestic orchestral arrangement that never comes.

“Pony Boy” (Human Touch, 1992)

Bruce Springsteen concluded Human Touch—ostensibly the more commercial of two albums he released in 1992—by covering “Pony Boy,” a song from the dawn of the 20th Century that found its fame on stage and screen. The sweetness of Springsteen’s rendition, spare and gentle, carries a romantic notion of Hollywood Westerns, an idea he’d play with through his modern-day cowboys on Western Stars.

“Your Own Worst Enemy” (Magic, 2007)

Released after a period where Springsteen dove deeply into folk music, Magic sounded bracing in 2007. Much of the record featured full-throttled rock’n’roll, but that made its excursions into orate pop all the more startling. Case in point is “Your Own Worst Enemy,” a song that seemingly adds additional instrumental elements with each passing second. Strings, sleigh bells, timpani drums, choirs–“Your Own Worst Enemy” feels like a marriage between the E-Street Band, Brian Wilson and baroque-pop pioneers the Left Banke. By relying so heavily on mid-’60s AM pop tricks, the record points the way toward the period charms conjured by Western Stars.

Girls In Their Summer Clothes (Magic, 2007)

“Girls In Their Summer Clothes” is another Magic selection which finds Springsteen besotted by the charms of orchestral pop. Shimmering like a summer heat wave, “Girls In Their Summer Clothes” is occasionally overheated—when the song ascends to its bridge, Springsteen wears his Brian Wilson homage proudly—but underneath this miniature symphony lies a sweetly sad heart.

“Queen of the Supermarket” (Working on a Dream, 2009)

Where “Girls in Their Summer Clothes” achieved a delicate blend of heartbreak and ecstasy, “Queen of the Supermarket” veers into outright bombastic territory. Springsteen daydreams of the girl who bags his groceries: a slight, flirtatious fantasy blown out to grand proportions thanks to its Phil Spector-esque Wall of Sound arrangement. In all its floridness, “Queen of the Supermarket” makes it plain that Bruce Springsteen had his eyes on re-creating the saturated Californian pop that dominated the airwaves at the end of the ’60s.

“The Wrestler” (Working on a Dream, 2009)

“The Wrestler,” heard apart from the Darren Aronofsky film for which it was composed, belongs to the long line of Springsteen portraits of bruised, wounded drifters–a line that stretches from his earliest records all the way up to Western Stars. This is a vivid sketch of a man hobbled by his own mistakes and vanity, a tale that would suit Western Stars, but its arrangement is impressionistic, not grand. Coming after “Queen of the Supermarket,” that restraint is something of a relief. The two songs are complementary in a sense; taken together, they provide a foundation for the multi-dimensional majesty of Western Stars.