“What remains of that tour? Nothing. Ashes.” This was Bob Dylan’s typically evasive response when questioned about the Rolling Thunder Revue, his notorious 1975-76 North American tour backed a ramshackle band that featured Joan Baez, Ramblin Jack Elliott, Roger McGuinn, T-Bone Burnett, and various hangers-on from the Manhattan art world. “It’s about nothing,” Dylan continued. “It’s just something that happened 40 years ago.” The interview comes from Martin Scorsese’s new pseudo-documentary about the tour, Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, out this week on Netflix. It’s the first on-camera Q&A Dylan has done in roughly 10 years, and the most revealing since 2004’s No Direction Home, Scorsese’s last film about him.

Dylan’s insistence on the tour’s ephemerality is ironic considering the existence of the documentary itself, which features varied footage of performances, rehearsals, parties, and other strange stops along the road. Scorsese had plenty of archival material to pick through, since Dylan and the gang had embarked on the Rolling Thunder Revue with a film crew in tow. Their task, ostensibly, was to collect footage for a four-hour meta-film inspired by the French New Wave. Released in 1978, Renaldo and Clara ended up a largely unparsable mess, despite some good performance footage and semi-staged backstage scenes; among other curiosities, it features rockabilly legend Ronnie Hawkins playing the character of “Bob Dylan.” The Rolling Thunder Revue itself was similarly haphazard: Dylan adopted a variety of creative approaches to which he would never return again, embracing the spirit of freeform collaboration, employing theatrical elements in the stage show, and importing a uniquely unhinged energy into his performances. It was ill-organized, wildly ambitious, and probably baffling to even many of his most accommodating fans. It also resulted in some of the most singular music and electrifying performances of his career.

The music itself was also carefully documented. The Netflix documentary is something of a companion piece to The Rolling Thunder Revue: The 1975 Live Recordings, a box set released on Friday, which contains 14 discs of professional audio recordings from shows, rehearsals, and the sorts of informal performances at offbeat venues that Dylan seemed to enjoy giving at the time. There’s a short set at a Massachusetts mahjong parlor, for an audience that mostly consisted of elderly women, and another at the Tuscarora Indian Reservation, home of Chief Rolling Thunder, the tour’s namesake. The box set is the second-longest in Dylan’s hefty discography of archival releases, which already has several recent entries that are daunting even for Bob completists.

The medium of delivery makes clear the intended audience for each: One is an easy click-through on Netflix; the other is basically a full set of musical encyclopedias, and will set you back about $100. Both have revelatory stories to tell about what makes the Rolling Thunder Revue worthy of its complicated, venerated reputation. But Scorsese’s film stands as the clear artistic triumph: built to move not just amateur Dylanologists, but also casually interested viewers. It serves both as a well-rounded exploration of a particular period in Dylan’s career, and as an ingenious subversion of the documentary form, in the tradition of Orson Welles’s intentionally deceptive 1973 experimental film F for Fake, and perhaps of Renaldo and Clara itself. Scorsese freely toys with the facts (Sharon Stone did not tour with Rolling Thunder, folks, despite what she may tell you), nodding to the absurdist self-mythology Dylan was cultivating on the tour while also shedding light on the actual reality of historical record.

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story presents a portrait of Dylan in the midst of a personally confused but creatively fertile period. In the late 1960s and early ‘70s, he cultivated a domestic lifestyle in upstate New York with his wife Sara and their children. He embarked on a stadium tour with The Band in 1974, and the time away from home and ensuing infidelities strained his relationship with Sara. He would touch on that relationship’s dissolution on his next studio album, Blood on the Tracks, an unusually personal release that fans hailed as a creative comeback. By the summer of 1975, Dylan was fully estranged from Sara and hanging out in Manhattan, frequenting clubs like The Other End, The Bitter End, and Gerde’s Folk City, reconnecting with old friends from his own folkie years and scoping the new local talent. This is where Scorsese’s film picks up. Early on, we see a performance from Patti Smith, who later bullshits with Dylan about their shared interest in the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud.

The fleeting nature of the interaction is indicative of the film as a whole, which gives only minimal, vignette-like context for Dylan’s personal life during the tour, going only as far as the archival footage allows. (We never see Sara, for instance, despite the fact that Dylan was frequently singing about her onstage and she tagged along for part of the tour.) On these reels, Dylan often feels as remote as he seemed to be from most people on the tour. Lead guitarist Mick Ronson claimed never to have spoken to him.

Still, there are quite a few revealing moments in the footage, which will doubtless take fans who might have expected a more by-the-numbers documentary off guard. Even some of the segments that were at least partially staged carry a charge. There is one exchange between Joan Baez and Dylan in which they touch on the sudden termination of their relationship in the mid-1960s. “Well, you went off and got married,” Baez says, diffusing a moment of nostalgia. In a 1978 interview with Playboy, Dylan discussed the scene, a moment of which ended up in Renaldo and Clara: “Seems pretty real, don’t it?…Just like in a Bergman movie. There’s a lot of spontaneity that goes on. Usually, the people in his films know each other, so they can interrelate. There’s life and breath in every frame because everyone knew each other.”

Still, there are quite a few revealing moments in the footage, which will doubtless take fans who might have expected a more by-the-numbers documentary off guard. Even some of the segments that were at least partially staged carry a charge. There is one exchange between Joan Baez and Dylan in which they touch on the sudden termination of their relationship in the mid-1960s. “Well, you went off and got married,” Baez says, diffusing a moment of nostalgia. In a 1978 interview with Playboy, Dylan discussed the scene, a moment of which ended up in Renaldo and Clara: “Seems pretty real, don’t it?…Just like in a Bergman movie. There’s a lot of spontaneity that goes on. Usually, the people in his films know each other, so they can interrelate. There’s life and breath in every frame because everyone knew each other.”

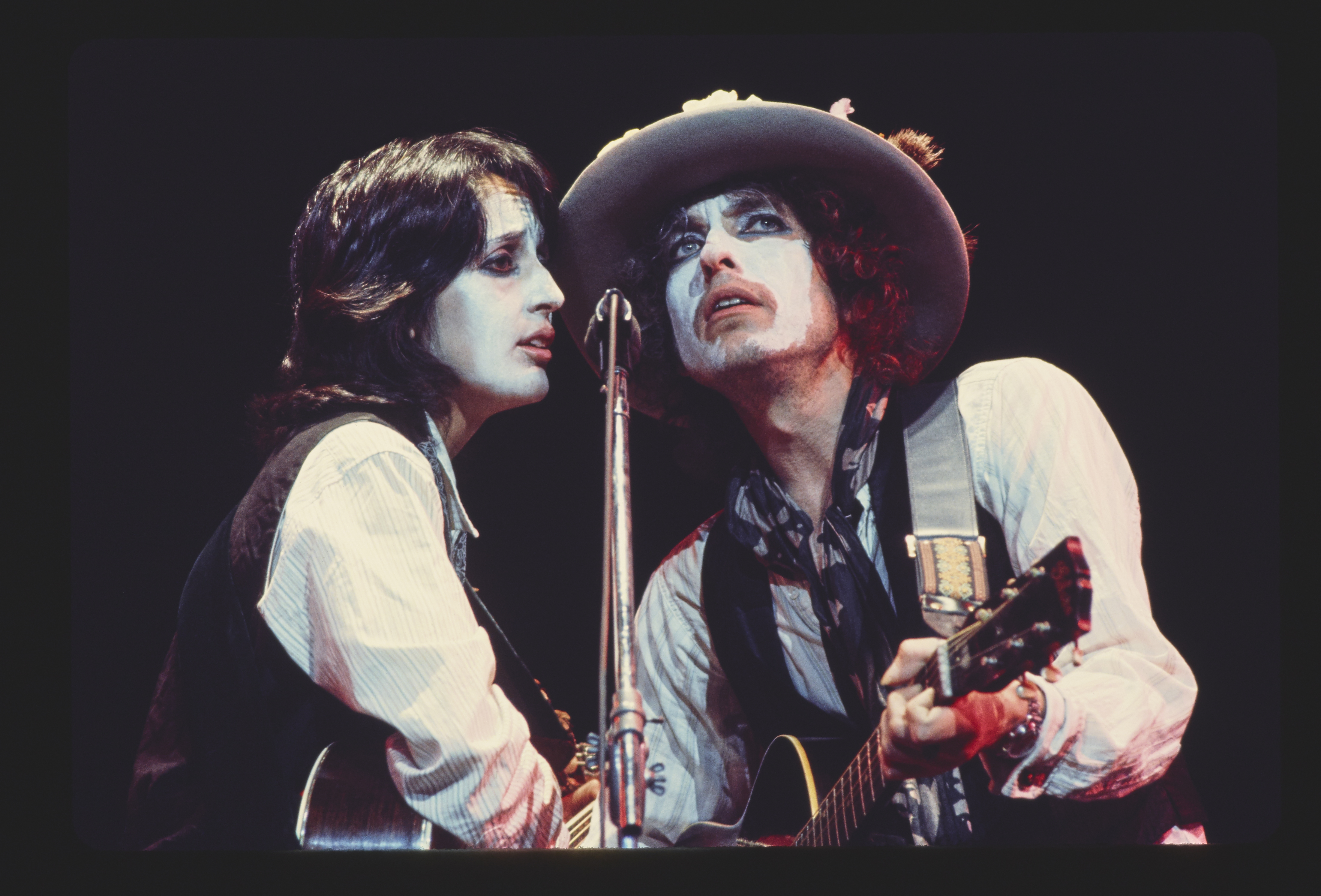

Baez and Dylan’s contentious and enduring attraction to one another is a side plot throughout the film. At one point in the tour, Baez began walking around backstage in a parodic Dylan costume. Elsewhere, an audience heckler yells “What a lovely couple” before one of Baez and Dylan’s acoustic duets, prompting Baez to shout back: “Couple of what?” Their duo performances were often near-yelled, amped up from the way they would have done the same songs in the early 1960s: the musical upshot, perhaps, of a repartee that is both electrifying and lightly caustic.

Other offstage scenes are so singular that it’s hard to believe they’ve never emerged before. In a segment that will threaten to move any fan of both Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan to tears, Mitchell, who tagged along on the tour for a while, teaches a brand new song of hers—it’s fucking “Coyote”!—to Dylan on guitar while reading the lyrics off a sheet of paper. (Perhaps not incidentally, it’s rumored that Mitchell wrote that future-classic song about the playwright and actor Sam Shepard, who was also among the Revue’s members, conscripted to assist with Renaldo and Clara.) Another outtake from the Renaldo and Clara footage features a long conversation between Dylan and the tour’s resident poet, Allen Ginsberg, at Jack Kerouac’s grave, punctuated by poetry recitation and harmonium jams.

The contemporary interviews are also worthwhile, providing the film with a needed lighthearted perspective. On the face of it, the Revue was a messy and misbegotten endeavor, and Scorsese doesn’t shy away from its absurdity and pretense. Neither does Dylan. For a notorious grouch, his interviews are surprisingly hilarious; believe it or not, he seems to be having something resembling a good time giving them. In his talking head moments, he tells anti-tall tales about the tour, delivering comic anecdotes about supporting characters such as tour biographer Larry “Ratso” Sloman (so nicknamed by Baez after the Midnight Cowboy character) and an invented, crotchety experimental filmmaker character, played by director Martin von Haselberg.

The contemporary interviews are also worthwhile, providing the film with a needed lighthearted perspective. On the face of it, the Revue was a messy and misbegotten endeavor, and Scorsese doesn’t shy away from its absurdity and pretense. Neither does Dylan. For a notorious grouch, his interviews are surprisingly hilarious; believe it or not, he seems to be having something resembling a good time giving them. In his talking head moments, he tells anti-tall tales about the tour, delivering comic anecdotes about supporting characters such as tour biographer Larry “Ratso” Sloman (so nicknamed by Baez after the Midnight Cowboy character) and an invented, crotchety experimental filmmaker character, played by director Martin von Haselberg.

But none of the backstage business would matter as much were it not stuck between beautifully restored footage of performances, which are the focus the film. Dylan assembled plenty of fierce backing bands over the years; in a field that also includes The Band, it would be difficult to argue for the Rolling Thunder ensemble—or any other group—as the greatest. But as one commentator observes, Dylan never seemed more like part of a band than he did here. You get the sense that this was a new group of friends that Dylan fell into the habit of partying with a lot, who together dreamed up a strange and ephemeral musical dynamic—one which he never would have orchestrated on his own, and which frequently seems slightly out of his control. In the studio, the result was one of the most polarizing and singular entries into his discography: the LP Desire, recorded before the Rolling Thunder tour and released in the middle of it. The band pushed the maximalist sound of the record to a new apex onstage, gaining mass as they picked up new members while moving from town to town.

The Revue band’s sound was a puzzling amalgamation of druggy ‘70s rock, outlaw country, and gypsy jazz. The crux of it was violinist Scarlett Rivera, who possessed a occultish je ne sais quoi. (In the film, Dylan spins a yarn about finding a sword and snake, among other treasures, in her dressing room.) Her playing had important commonalities with some of the sounds that interested Dylan at the time, including the florid gypsy guitar music he had heard on a bender in France the previous year (the inspiration for “One More Cup of Coffee,” allegedly). No image exemplifies the contrasts of the band better than stage footage of Riviera, in black garb and ornamental face makeup, standing alongside Mick Ronson with his blown-out platinum ‘do, recently displaced from David Bowie’s band and looking that way, firing off muscular licks and searing solos through flashy pedals.

But the most striking performance footage, obviously, is of Dylan himself. At many of the shows, he was in full theatrical mode, bug-eyed and decked out in ghoulish kabuki-like face paint. The slightly demented approach compliments the narrative songs of Desire well. The highlight of the performance clips, and many Rolling Thunder sets, is “Isis,” during which Dylan would put down his guitar, mug for the audience, and gesticulate wildly in the mode of expressionist theater. Songs like “Isis” and Desire’s classic opener “Hurricane” were epic stories, and it was incumbent upon Dylan to put them across clearly to audiences that were not yet familiar with them. He often seemed estranged from older material, attacking it in a more subdued manner. In the solo performance of his 1965 favorite “Mr. Tambourine Man” that introduces the film, Dylan sounds like he’s singing both with and against the emphasis of its psychedelic lyrics, which feel like the handiwork of a different songwriter from a different era.

But the most striking performance footage, obviously, is of Dylan himself. At many of the shows, he was in full theatrical mode, bug-eyed and decked out in ghoulish kabuki-like face paint. The slightly demented approach compliments the narrative songs of Desire well. The highlight of the performance clips, and many Rolling Thunder sets, is “Isis,” during which Dylan would put down his guitar, mug for the audience, and gesticulate wildly in the mode of expressionist theater. Songs like “Isis” and Desire’s classic opener “Hurricane” were epic stories, and it was incumbent upon Dylan to put them across clearly to audiences that were not yet familiar with them. He often seemed estranged from older material, attacking it in a more subdued manner. In the solo performance of his 1965 favorite “Mr. Tambourine Man” that introduces the film, Dylan sounds like he’s singing both with and against the emphasis of its psychedelic lyrics, which feel like the handiwork of a different songwriter from a different era.

In one of the film’s archival clips, an interviewer asks Joan Baez whether was Dylan consciously singing in a “different,” more feral voice on the tour. Baez doesn’t exactly acede, but acknowledges that there was a distinct “Rolling Thunder energy” to the performances. If the documentary footage leaves you with any doubt about whether Dylan was able to sustain that energy every night, the attendant 14-disc box set makes it eminently clear that he was. At a time when cultural interest in the Grateful Dead is surging, however, the Rolling Thunder box feels like it couldn’t have come at a friendlier time. It’s divided show-by-show, with a disc of odds and ends from stops off the road. The best way to digest it recalls the procedure of the modern, committed Deadhead: surf around, pick a show that looks good, and settle in.

But these are very different kinds of rock shows from the average Dead date. There are not several decades to sift through, the pool of material is smaller, and the songs offer limited room for improvisation. That is all to say: listening to hours of the so-called “Rolling Thunder” energy can be punishing. The band delivered a blistering, full-throttle performance every night during the hour or so Dylan himself was on stage, fueled both by Dylan’s own aesthetic vision and, inevitably, a lot of cocaine. (The rest of the proceedings, which periodically included a set of new material from Joni and readings by Ginsberg, sometimes lasted up to three hours longer.) Dylan’s sets had relatively little dynamic variation; sometimes, his performances seemed to be mocking the songs as much as supporting them. By the third or fourth sardonic runthrough of, say, “The Lonesome Ballad of Hattie Caroll,” it’s hard to come to any new revelations. Streamlined compilations of this music—the Bootleg Series Vol. 5 and the botched Renaldo and Clara soundtrack Hard Rain are great primers—distill this period well.

However, for devotees, there are plenty of fascinating musical tropes and outliers to relish. Several hours in, you may notice the band’s propensity for falling into something like island music. “It Ain’t Me, Babe” gets a reggae aspect, thanks to Ronson’s wah-wah guitar. The group’s take on the spartan country of John Wesley Harding’s “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” juxtaposes Baez’s close harmony with a calypso backbeat, and “I Shall Be Released” sometimes sounded like it could have been played in the middle of the night at some decrepit Hawaiian resort. The playful music continent-hopping of Desire spills over everywhere.

The Rolling Thunder band’s electrified take on “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” best distills their defiant and alienating side, retooling one of Dylan’s most poetic “protest” compositions of his acoustic era as a Muddy Waters blues on amphetamines. In his later years, Dylan has toured often, and indulged a certain perversity as a live arranger, viewing his songs as raw putty to be molded according to his whims at any given moment. The original melody might recur, or it might always feel slightly off; the chords might change at the expected time, or they might never change at all. (To biographer Howard Sounes, guitarist Ed Stoner recalled that he’d stand behind Dylan and watch his hand: “You can anticipate when the chord is going to change by watching the muscles relax.”) You could argue that the Rolling Thunder tour marks the point when Dylan’s approach to performance and interpretation definitively loosened, and when he became obsessed with touring as a way of life, rather than just a creative outlet.

In Rolling Thunder Revue, Scorsese cuts frequently to a shot of Dylan driving the RV in which he stayed during the tour, while the rest of its shifting lineup packed into in the bus. Dylan’s serene face suggests that he is imagining himself as a truck driver or some other romantic itinerant character—that there is something in that constant movement which suits his sensibilities on a level beyond music. The film ends with a dizzying scroll of Dylan’s tour dates from 1975 to 2018; during many of those years, precious few days are left unaccounted for. In the movie, both Dylan and Rubin “Hurricane” Carter—the middleweight boxer convicted of murder whose long imprisonment is the subject of Dylan’s “Hurricane”—recall a line Carter used to say to Dylan when they ran into one other: “What are you searching for, Bob?” Like any good Bob Dylan story, both the film and the box set leave you the same lingering question.

https://open.spotify.com/embed/album/7I8ARvRuRzDghzsItBARZK