Spin’s Rap Monthly column interviews an artist making waves, reviews selections from the past month, and holds some lame shit accountable.

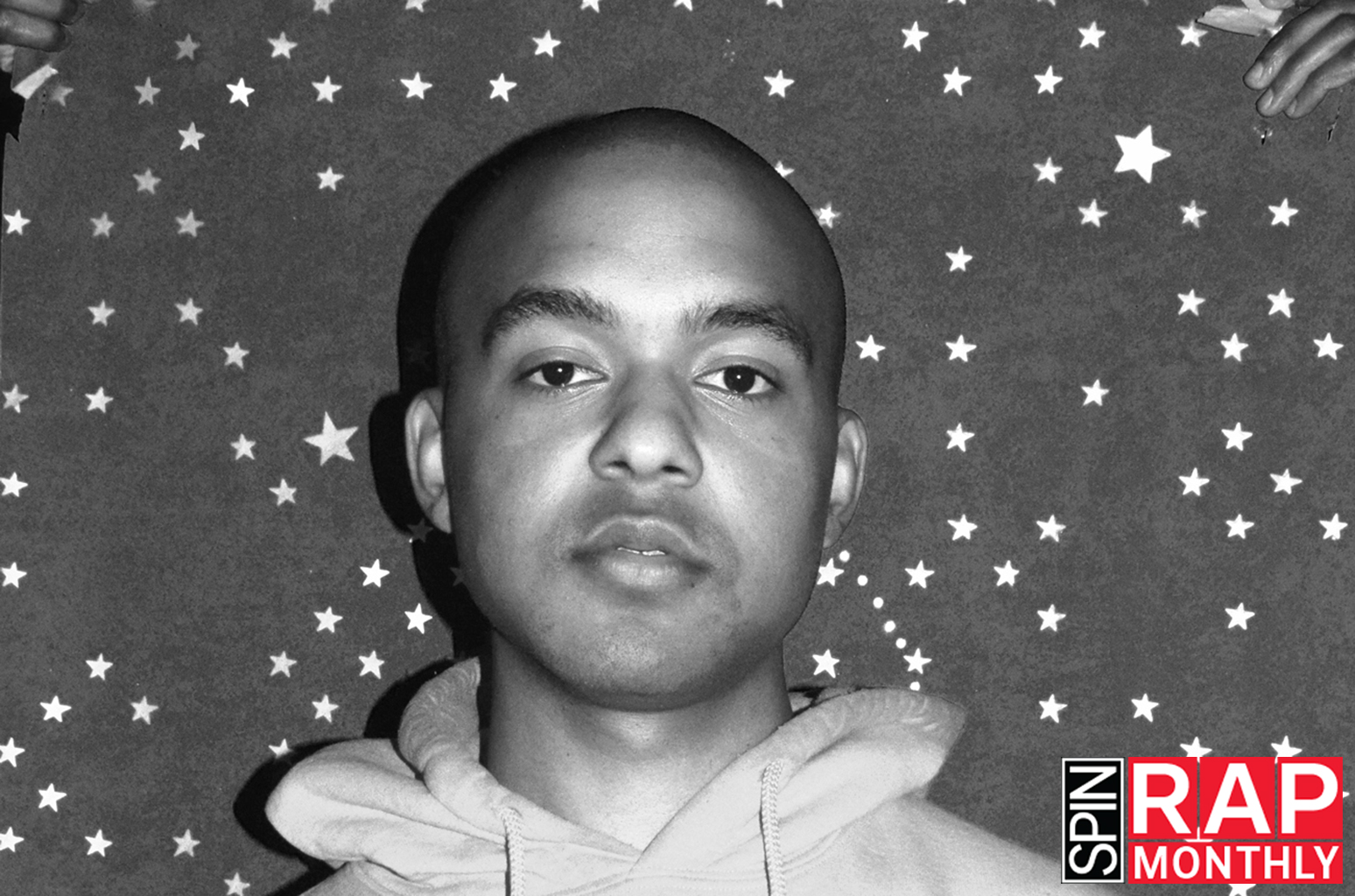

Jasper Marsalis is in London, preparing to exhibit sculpture at a repurposed bookstore, talking to me over the phone about drawing cars. “I wanted to be a car designer originally. I just had this obsession,” he says. “I took this design class when I used to live in Los Angeles and the instructor told me I couldn’t draw a car in a specific direction because I guess there’s standards for how you make a mockup.” You’re supposed to sketch car body profiles, he says, with the bumper on the left. “Something about that really rubbed me the wrong way. I was just like, I’m gonna just do it my way.”

Marsalis, who records music under the name Slauson Malone, was particularly interested in car customization: that mischievous Los Angeles art of hydraulic suspension systems and airbrushed paint jobs that transform stock cars into lowriding spectacles. He also likes the mutable forms of reggae dubplates, soul covers, and Legos. His new album A Quiet Farwell, 2016–2018 densely assembles sounds of dissonant origins, fidelities, themes, and tones into finely detailed collage, occasionally spliced with rapping. It’s best heard in full. He damages samples and vocals, drowns verses in the mix, privileges distortion, and fills space with tape hiss. Lyrics appear and disappear abruptly but leave a mark. “Hoping that the reaper don’t catch me / Bring me down like six feet / Thoughts of suicide watch the time pass by,” he raps on “Fred Hampton’s Door, Farewell Sassy– …na” before a screwed voice juts in singing Tony Williams’ refrain “I love you more when it’s over.”

Restless revision defines the music, which finds an unsettling beauty as it pivots between harsh noise and melody, new sounds and old, hope and pain, iterating and reflecting on what has been. The album features four (numbered out-of-order) songs titled “Smile,” each featuring a different rapper and opening with versions of the same lyric, “Smile at the past when I see it.” Several tracks are dated to police murders and begin with variations of a siren-like moan. On “THE MESSAGE,” Marsalis plays the guitar riff and recites the chorus (“You can’t stop me now”) from Barret Strong and Normal Whitfield’s “Message From a Black Man,” first recorded by the Temptations, then some dozen others, its various forms sampled in rap songs many times over.

The project invites deep reading whether or not you read its manifesto, where Marsalis writes things like “I see us collectively Smiling, imaging a place called the Past that isn’t” and cites the writer and scholar Saidiya Hartman. Hartman’s 1997 book Scenes of Subjection reckons with art that replicates and perpetuates trauma, and attempts to disfigure historical examples as she goes — a useful frame for Marsalis’ Goth Madlib style. We discussed her, as well as Mark Leckey, Jack Whitten, Marcel Duchamp, Nana Adusei-Poku, Steve Reich, David Hammons, and Prince Jazzbo. A Quiet Farwell is also something like a breakup album. Marsalis helped found the New York free-jazz-psych-rock-experimental-hip-hop collective Standing on the Corner that has produced music for Earl Sweatshirt and Solange. He left the group last year. We discussed that, too.

The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What is your relationship with New York these days?

I don’t know, man. It’s a bad relationship. It’s like, y’all have to sleep in the same bed, but y’all hate each other. I don’t know. I can’t really answer that question too well. It’s just a place to be. It just has this like, blatant hostility that, I don’t know, it’s exciting, but it’s also, I don’t know, it’s fucking New York, man. It’s just a place. I can’t really — my opinions are always shifting on New York so I can’t really answer. Some days it’s good, some days it’s bad.

What is your relationship with Standing on the Corner?

People love that question. I’m not in the group anymore. It’s that simple. Just: I was in it, now I’m not.

How did you come to that decision?

Most of it is personal, so I can’t really talk about that. But I just think there were ideological differences between us and they weren’t gonna get resolved, or like that. So I just thought it would be a smarter decision for everybody if I just wasn’t part of it anymore.

What did Standing on the Corner originally mean to you ideologically?

It was a space for us to take refuge from a lot of the absurdity of the world. I think a lot of us found each other in predominantly white spaces as black people and, I don’t know, we all kind of related for that reason. We just wanted to make something happen that meant something to us. It was a very freeing experimental space to be in. Red Burns is a true testament to those ideas.

I’m interviewing you for a column that’s nominally about “rap music.” You’ve said in the past that you have an antagonistic relationship toward hip-hop, but tagged this project on Bandcamp as “hip-hop.” Not to belabor this point, but what informed the categorization? Do you still consider that relationship antagonistic?

I just think it’s hip-hop. I mean, it is hip-hop. That’s what it is. There’s no denying it. I just have a strong vehemence against genres in general. It’s a necessary evil because you have to categorize things or else they’ll just be nowhere, you know what I mean? I think the term is like a way to box things in, you know? But I don’t know. I felt like fighting it was kind of a pointless battle. Like, why? Why even fight it? It just is what it is. So that’s why I decided to label it hip-hop, rap.

What is the battle?

I feel like I’m about to go from zero to one hundred in about one second. But it’s just a way for people — hold on, let me set myself up right. It’s just a way for people to ostracize black people or something. Like the term: hip-hop. Even when I was doing the Standing on the Corner records, the first record, which is very indie-esque, was still labeled as a hip-hop record. Gio and I had some frustration about it, but it was just a reality that was kind of important to accept. But that’s my main blowback on it. People come with so much baggage to the music before they even listen to it. I guess where I differ, despite the antagonism, I think I was kind of afraid of that baggage. But I think this time around, I don’t really care anymore. Or it’s not that I don’t care, I just think it’s more considered now.

Your dad is famously antagonistic toward hip-hop. How did you understand his critiques growing up?

Well, you have to understand, I’m his son. I’m not like a student. You know? I’m not going to his class. You need to first really understand that. But I completely understand where he’s coming from. That’s why I need you to understand like, I’m his son. So I mean, I think most of his issues are formal issues with the music, which I kind of agree with, generally speaking. There is very strong restrictions on the music that define it as what it is. That doesn’t allow for a lot of growth, formally speaking. But I think we’ve seen in the past couple years a lot of albums that have come out of the genre which have completely destroyed expectations, which is super exciting.

When and where was this album made? What was the process?

I had four instrumentals that were made around 2016 that I had sitting on my computer. Medhane and I were working on the next Medslaus project and that was kind of slowing down. I had these instrumentals and I was trying to work on them, but people weren’t really feeling it. I sent it out to a couple different people. No one was really feeling it. Eventually, because I had left the band, I just had nobody really to work on these songs with. I think the first song that really started to come in fruition was the song with Pearl de Luna. She sent me back the vocals and I was just like, what the hell? It sounded so good. I was like, maybe if I keep doing it like this, like, I’ll have something. The album started out as a pretty traditional, I guess, producer album. Like, features. But I think there was a lot of missing material. It felt kind of empty. So I was just kind of adding more and more thematic elements until I got this cohesive idea down.

At what point did the pieces start to cohere as what they would become?

I think when I came to London six months ago. I had everything kind of arranged in Ableton as a one-track file. I was just listening to it over and over. As an assignment to myself, I just started writing about it, writing about how the songs made me feel. I had this whole idea for this full-length video that was gonna accompany the music and I think that’s when the idea started to come together. Yeah, thinking about the album visually helped me queue certain things together. And the scream, actually, the silent scream, when that came together, I was like, oh yeah, I think I got this.

What was that visual idea?

Well, I don’t want to give too much away because I’m still trying to make it happen. I’ll say this one thing. One thing that kept on coming to my mind was a palm tree. There’s a Cyprien Gaillard art piece called “Nightlife 2” and it’s just these palm trees in slow motion. I just kept on thinking about that. Palm trees being decontextualized as if they were dancing, but then there’s this cool doubling with the hurricane, making something violent look humorous or something. I don’t know. I’m still thinking through it.

Did you give directions when you sent out instrumentals?

Yeah, so for Pearl, I was just like, can you personify a hurricane? And she did an amazing job with that. Max, he has an album called Smile. Well, I’m kind of messing with the order. The first song I recorded was with Caleb Giles and we didn’t really have a direction for that because that was the first song I recorded. He just has that bar, “Smile at the past when I see it.” I just kept on thinking about it over and over again. It just made no sense. And I listened to Max’s album Smile, and then I was like, damn, there’s a connection here with what Caleb’s saying and what Max is saying. So I told Max, I was like, yo, can I get one of the a capellas off Smile? He was like, nah, let me write something. So I sent him the instrumental and then I was like, can you maybe do something that has to do with smiling at the past or whatever? It kind of just snowballed, I guess. Accumulations.

The album strikes me as archival in some ways. Do you consider the music to be an act of archiving, or in conversation with archives?

I have a very bizarre relationship with archives or the idea of the past as being a tangible thing. So I would really kind of fight you hard against the word archive because it kind of implies that the ideas are dead or no longer with us. So I don’t really consider it like that. But I see exactly what you’re saying because of the sampling. There’s a lot of old stuff on it. I see it more as like, just rebuilding, or not even rebuilding. It’s like getting a Lego set and then just not reading the instructions. That’s how I would want to put it. Because all the Lego pieces, you can buy a Lego set from like, I don’t know when Legos were invented, but you know what I’m saying? It doesn’t matter which year you buy the Lego set from, they can still all fit together, for the most part.

How did Saidiya Hartman’s writing inform your work?

Well, the biggest thing I took away from Scenes of Subjection was how artists reenact their traumatic experiences. What does it mean to literally re-hyphen-present trauma? Are you just giving agency to this stuff? Specifically as a black person, I think about other black artists who use blackface or feel a necessity to represent slavery in various capacities. Are you just replicating this? An analogy I like to bring up is like — just so it’s not so black-white-black thing — is movies about Nazi Germany. It’s like, in a weird way, you’re continuing the existence of Hitler through his representation. That concept alone is such a hard thing to come to terms with as an artist. That kind of fueled, those questions just kept me going. I mean, still right now, I still think about that on a regular basis. She made me really realize the scope of white supremacy. Even artists who believe that they’re forming new ideas around black identity are just replicating various facets of white supremacy.

How do you think about the act of sampling in that context?

A friend of mine who goes by ReallyNathan — we have a couple of NTS shows together. We still have this show that’s still in the works, but it’s about Duchamp and sampling because there’s this weird idea of ownership in music that doesn’t seem to be a problem in art, you know? Sampling is just — this kind of goes back to what we were talking about with the hip-hop genre thing. I think it’s also one of those things that has these negative connotations to it, but are really just like “mine,” you know, like in a military mine, like a proximity mine. It’s a proximity mine for like — ahh, my language is falling apart as I’m trying to talk about this. It’s like a proximity mine for white power or some shit.

That’s a really bold thing to say, but it’s like, the people who are really concerned with getting these samples cleared and shit are obviously the labels so they can get money from unfair usages. So it really has nothing to do with the music. But you have somebody like Steve Reich, who did “It’s Gonna Rain,” who, I’m almost certain without the person’s consent, sampled their voice and made this ten-minute long piece, but people are parading it as an avant-garde work. I don’t know, man. Sampling is awesome, but I also acknowledge the limits of it. So that’s why on the album a lot of the stuff sounds really strange because certain things are replayed sometimes, and certain things are not samples, started out as samples, but aren’t anymore.

Did any specific memories inform the album?

Not particularly, just because I have such a disliking for ideas of the past and nostalgia. So I would like to believe that a lot of this album is in the form of presentness. It’s being in the now, so to speak. There’s not much in there that I could say is a direct result from me remembering something in my distant past. I will say, though, that the album really was a coping mechanism for feeling like losing a lot of people in my life. So in that sense I guess I could make some sort of claim there.

Are there any ideas you want to revisit or finish on?

Yeah, I feel like something really important to me is just emphasizing to people, or what I hope gets across in the album is that, like, nothing is also like a thing, and nowhere is also like a where. I don’t know, I feel a lot of times people get caught in decisions on defining identities for themselves, but sometimes you just don’t know, and that’s also a possibility. I really hope that’s something that people feel comfortable in that space, they feel more comfortable in that space. I think that’s really the most important thing.

Look Back At It

In April, Spin enjoyed rap music that taunted prisons, polished formulas, and convened mosh pits. These and other recommendations below.

03 Greedo – Still Summer in the Projects

Prison time didn’t stop the prolificacy of 03 Greedo, but it did hasten it. After being sentenced to 20 years for gun and drug possession last June, the rapper and vocalist doubled down on his already-sprawling output, using the forced isolation to write and produce over 600 songs, many of which have proven to be among the best of his still-nascent career. Last year’s God Level showed a side of Greedo aching to give voice to the stories cut short by his jail time, while The Wolf of Grape Street split the difference between breezy party anthems and the darker thoughts that naturally follow someone locked away.

In theory, Still Summer in the Projects should skew closer to the former. With production helmed by Mustard, the beatsmith known for almost single-handedly defining the West Coast sound of the 2010s, the latest Greedo release is premised on a return to the lighter side of his music, finally reaping seeds sown as far back as 2016’s Purple Summer. But three years and countless releases later, even the lightest Greedo tracks wrestle with heavier issues, making Still Summer in the Projects one of the strangest and most beguiling releases from the rapper to date.

Take “Gettin’ Ready.” Over keyboard chords and a steady 808 bass line, Greedo sings about the women he can’t be with due to his circumstances. Simultaneously showered with money and understandably absent from the picture, he writes optimistically about the connection he can hopefully establish through his music, even as wealth and fame constantly threaten to tear his situation apart. Melodically, it’s one of the release’s softer, more R&B-leaning moments, but it reveals a side of the rapper as enamored by his recent celebrity as he is troubled by the circumstances it’s created.

To be fair, a considerable amount of the release breathes with the kind of lightness expected of a Mustard release. Tracks like “10 Purple Summers” and “Wasted” are clear tributes to Los Angeles, recruiting YG for a club-ready hook on the latter track. Even “Trap House,” the rapper’s single with Shoreline Mafia, shows Greedo is still always down to cut loose, even in the midst of an otherwise heartfelt release. Ultimately, the album reveals a newfound fluidity between the two styles, with Greedo as much a stylist as he is an expert rapper and performer. –Rob Arcand

Shy Glizzy – Covered N’ Blood

Shy Glizzy, perhaps the most resilient street rapper in the District of Columbia, has settled into a consistent musical formula at this point in his career. His last few projects crawl along a laid-back tempo and shuttle between the same few inexorable melodic cadences. Still, the rapper’s music is a product we enjoy–sturdy and unmistakable. We buy the newest upgrade, even if there are a few glitches, or we sometimes wish we could have some features offered by competitors. His newest project Covered in Blood bears out the same basic musical theses as last year’s more sensuous and light-hearted Fully Loaded, but stands out as the most melancholic of his projects of the past three years. His hooks and flow patterns sometimes verge on the anonymous, especially when coupled with the leaden production. But when Glizzy strikes the right balance between his blunt musical formula and sharply realized lyrical scenarios, he often happens onto a great song.

The strongest tracks build tension subtly, following the contours of a dramatic monologue. “Pryme Time” combines all of the lyrical postures and flows which suit Glizzy best, running through boasts, insults, and expressions of lust, grief, and anger within a verse. Passing moments of sensitivity, situated in a clear setting, fit the musical treatment best: “Lately ain’t been understanding life, I just know that I’m blessed / I just left Miami, took a rest while on the jet / I had to bury my OG, I’m gonna miss that man to death / Last of a dying breed, ain’t many real n*ggas left.” It’s easy to wish for some variation in BPM count and a respite from the overcast atmosphere, but this is yet another Glizzy tape worth combing through to find these sort of resonant, crystalline moments. –Winston Cook-Wilson

Rico Nasty – Anger Management

Rico Nasty and partner-in-crime producer Kenny Beats designed her first release since last year’s star-making album Nasty for the festival stage. The EP leads with a pair of abrasive beats on “Cold” and “Cheat Code” that center bass-boosted drops, industrial kinks, and Rico’s harshest register. These moments articulate an oddly logical extension of the pair’s moshy nu-metal tendencies into EDM terrain that suits both Rico’s summer touring schedule and her confrontational style. “Big T*****s” and “Mood” are only slightly less LuckyMe and serve similar ends. Danny Brown’s Old may be a useful reference, though Rico has far more fun: hotboxing Benz trucks in a Jason mask, eating oxtail, rubbing money in your face, snarling punchlines like “Took the air out of you, Tom Brady.” For a moment, “Sell Out” pauses the ruckus to quietly reflect on commodifying fury, but ultimately this tape reaffirms Rico’s singular rowdiness. – Tosten Burks

Kevin Abstract – ARIZONA BABY

Kevin Abstract is 22 and, like most young people unsure of themselves, he has a habit of using other people’s aesthetics to craft an identity. Listening to his music, it’s very easy to pick up on the fact that he grew up idolizing Odd Future and Kanye. Despite how obvious his reference points are, his music manages to be mostly good with the occasional great record wedged in there somewhere; it’s his confessional, tortured, and vulnerable persona which elevates his music when its at its best. With the release of his new album ARIZONA BABY, Abstract has made his tightest work yet with a reflective, incredibly personal portrait of the pains of being young and famous. As part of the supergroup BROCKHAMPTON, he’s achieved a surprising level of notoriety and success, but Abstract is better as a solo artist, and his music acts as a sort-of time capsule capturing a man finding himself as a person and musician. The album may not light the world on fire but it has a real and lively spark that is hopefully the first step to great things. –Israel Daramola

Kelow Latesha – TSA

Kelow Latesha hails from Maryland but, at her best, raps like the yappy Texas goofballs turning minimal post-snap toy beats into viral dance phenomena. She sets a mocking tone from the top, delivering “I might fucked your bitch but really can’t remember, ooh yeah” on “Not You Then Who” in a caricatured falsetto so rude that it doesn’t matter whether or not she did the deed. TSA‘s best moments foreground her vocal eccentricities: check the “U Can’t Touch This”-interpolating “Hammer Time,” built around a sloppy “pfft” ad-lib, for one of the best mouth-sound beats since the Cool Kids’ “What Up Man.” It’s not all style, either. Separating Kelow from the likes of 10k.Caash are runs like this opening confession on closing track “Call Security,” which earns its crescendoing rage: “Hoe, I cried my eyes and wiped them dry ’cause you ain’t wanna hear my pain / At the same time I ain’t wanna feel myself go and complain / At the same time can’t associate myself with no weak lames / Non-expressive so I’m aggressive, WHAT THE FUCK IS YOU SAYIN’.” –TB

Plus: The Weeknd’s Memento Mori Episode 5, Beats 1’s biggest flex since More Life, premiered over a dozen unreleased tracks from XO’s circle, not least prime Uzi collabs with Lil Durk and Gunna that may never see official release; Fredo Bang’s Big Ape, second generation Kevin Gates-core for when you’re not trying to cry to NBA Youngboy; Rhys Langston’s Master Fader on Speed Dial, L.A.’s wittiest beat scene rap project in years; Pyramid Vritra and Wilma Archer’s Wilma Vritra, an album with peculiar ambitions, plays like a yacht rap film score; Pivot Gang’s You Can’t Sit With Us confirms Saba’s brother Josephh Chilliams is the more entertaining sibling.

Get Out the Way

I think often about Marshmello producing Lil Peep’s first posthumous single. Over the past year, market forces have demanded that the pseudonymous super DJ, a hip-hop outsider, maximize his or her reach by glomming onto rappers’ streaming audiences. The dynamic has produced generic and soulless collaborations with Peep, Migos, Juicy J, Roddy Ricch, Tyga, Chris Brown (inevitably), and Bay Area phenoms SOB x RBE. Caught between regional success and true major label scale, the latter quartet, best at breakneck speed, are forced to do things like record passable verses over mid-tempo D-grade Mustard beats because tons of children love the producer’s mask. All three songs on the Roll the Dice EP are cynically constructed and forgettable, but I guess I’ll make you listen to “Don’t Save Me.” –TB