This week, to mark what would have been Townes Van Zandt‘s 75th birthday, Fat Possum Records released Sky Blue, a posthumous album of previously unreleased recordings from one of the greatest American songwriters who ever lived. Sky Blue, recorded simply in a low-key session at a friend’s studio in 1973, contains two Van Zandt compositions that are genuinely new to the world, a handful of rough versions of tunes he’d either already released or would release later, and a few covers. It’s a fine collection of work, but would make a strange introduction to Van Zandt’s canon for anyone who isn’t already a devoted listener.

If that’s you, read on. Below, we’ve collected 10 essential Townes Van Zandt songs from across his catalog: not a definitive list of his “best” songs, but one that we hope will give a sense of his range. He was a Texas-bred country songwriter with a painter’s sense of color and shape, a poet’s devotion to meter and rhyme, a tender heart, a tough exterior, a way of making small details feel universal and sweeping observations seem intimate.

Van Zandt had a reputation as a tortured and wayward soul, one that he didn’t always discourage: “You have to pass out the razor blades before the end of the set,” he once said about his concerts, and he lived a life full of tumult and solitude before dying at 52 years old in 1997, due to complications from years of substance abuse. But he also had a deep and warm sense of humor, one that evinced an almost childlike outlook on the world. His album Live at the Old Quarter, which documents a series of 1973 solo concerts in Houston, is a treasure, as much for the jokes and banter between songs as for the songs themselves. In one joke, two drunks are arguing outside a bar about whether “that object up in the sky” is the sun or the moon. They ask a third drunk, whose answer is as ridiculous as the argument itself, but gets at something true about the essential absurdity of living as a person in the world: “Aw, I don’t know, man. I ain’t from this neighborhood.”

Steve Earle, one of Van Zandt’s many acolytes, famously said, “Townes Van Zandt is the best songwriter in the whole world, and I’ll stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say that.” It’s hard to argue with him.

“Rex’s Blues”

“If you cut cards with Rex, you’ll get a 3, he’ll get a 2, you know what I mean?” Van Zandt said, introducing his performance of “Rex’s Blues” at the Old Quarter in 1973. (“Rex’s Blues” also appears on Sky Blue.) On the face of it, the song is a character study about an alcoholic with rotten luck at cards and relationships, the real life inspiration being Townes’ friend Rex Bell, who co-owned the Old Quarter. Townes’ guitar playing is “blues” in the Mississippi John Hurt sense of the term, with the fingerpicking sketching out a rollicking ragtime feel. Despite the jaunty accompaniment, the song eventually takes on the tone of a suicide note. Townes sketches the entire spectrum of life’s experience in playful, sad little phrases. His songbook is full of references to mortality, and “Rex’s Blues” gets there with two chords and a few lines that are good enough to mean almost anything you might want them to. It includes a candidate for Townes’s best stanza of all time, a reflection of the textbook down-and-out feeling of being trapped in a hopeless role, a useless burden to the world and one’s self: “I’m chained upon the face of time / Feelin’ full of foolish rhyme / There ain’t no dark till something shines / I’m bound to leave this dark behind.”—WINSTON COOK-WILSON

“Waiting Around to Die”

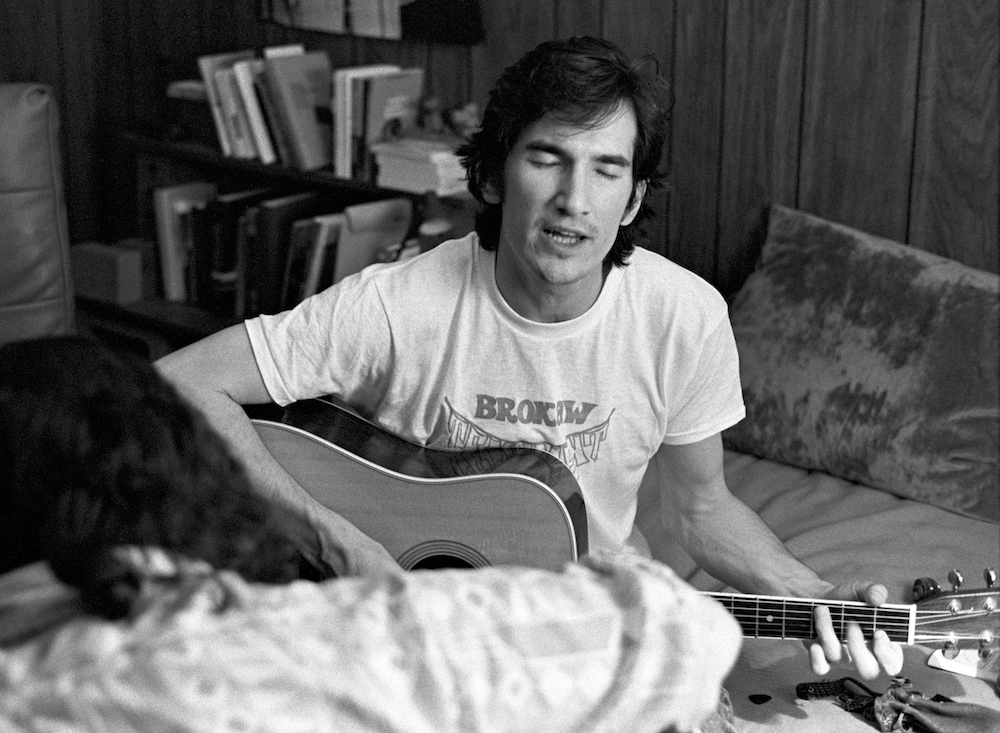

The most remarkable sequence of Heartworn Highways, a cult-classic impressionistic documentary about the outlaw country movement of the mid ‘70s, involves Van Zandt and Seymour Washington, a retired blacksmith born in 1896, whose home became an unlikely gathering place for Austin’s musicians and other associated hippies at the time. “I’m fixin’ to interview Uncle Seymour Washington,” Van Zandt announces boyishly, and Washington begins recounting his years of hitchhiking to work when he couldn’t afford transportation, then outlining the finer points of making and applying horseshoes. Soon, he is sharing wisdom on the virtue of moderation, especially when it comes to drinking whiskey—wisdom which is clearly intended on some level for Van Zandt himself, who battled with alcoholism and addiction for nearly his entire life. The singer bounces in his seat as he listens, mugging for the camera and the other people in the room. If he recognizes the weight of what Washington is trying to tell him, he doesn’t show it.

Later, Van Zandt performs “Waiting Around to Die,” a ballad most famously recorded for his 1969 self-titled album, but given its definitive performance here. It’s a brutally apposite choice for the moment, like a conscious rebuke from Van Zandt to his own earlier insouciance. His narrator boozes, gambles, hops trains, commits a robbery, and ends up addicted and in jail—maybe because of a childhood wracked by domestic violence, to which he alludes in the second verse, or maybe because doing those things just seemed “easier than waiting around to die,” a line he repeats like a disastrous mantra. The camera first focuses on Van Zandt’s fluid fingerpicking, but soon moves to Washington’s solemn face over his shoulder. We can assume from his tales of hardship that this man is not given to crying easily. By the end of “Waiting Around to Die,” he unashamedly weeps. You may find yourself doing the same.—ANDY CUSH

“For the Sake of the Song”

Van Zandt wrote much of his best work in the black-hearted, post-relationship space between crawling back and moving on. On “For the Sake of the Song,” the Texas native spins a masterpiece of tears-in-your-beer balladry, weaving his own grief through the story a woman who wants more than he can give. “Does she actually think I’m to blame/ Does she really believe that some word of mine could relieve all her pain?,” he sings, as much to himself as to any audience he’s in front of. No one does heartbreak like Van Zandt, but even at his bleakest, he remains poised. Sometimes you just have to sing for the sake of the song.—ROB ARCAND

“To Live Is to Fly”

Sometimes, Van Zandt was the sly storyteller, spinning elegant fables about bandits and lawmen. Other times, he was the heartsick confessionalist, singing wrenching first-person narratives of love and loss. Occasionally, he slipped into another identity: the hardscrabble sage, dispensing zenlike aphorisms over a drink and a smoke. “To Live Is to Fly,” from 1972, is a classic of the latter category, a treatise on getting up each day and getting through it, no matter how high or low. The arrangement is quietly majestic, and every line is a gem. Some are even more than that: “Living’s mostly wasting time / And I’ll waste my share of mine / But it never feels too good / So let’s don’t take too long.” You could do a lot worse for a guiding philosophy of life.—AC

“Fare Thee Well, Miss Carousel”

Musically speaking, few Van Zandt songs are as perfectly constructed as the melodic, bittersweet highlight of his self-titled album, “Fare Thee Well, Miss Carousel.” It’s not what Townes is known for, but the song boasts a perfect power chorus, supported by a dynamic full-band arrangement. The uncredited drummer’s bold choice to completely dip out for the verses—outside of a few erratic, claptrap fills—is crucial. The unusual approach makes it clear that Townes was not accustomed to integrating heavy drums into his songs, but it justifies their use here, where they function like a strange narrative device. With his anecdotal sketches of “Miss Carousel,” “the drunken clown,” and “the blind man with his knife in hand,” Townes’ symbolistic lyrics sometimes recall mid-’60s Dylan. But they are imbued with that particular Van Zandt brand of melancholy, broken up by couplets that zoom out to reflect on the entire human condition.—WCW

“Snowin’ on Raton”

Van Zandt recorded far less often as he entered middle age in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but he never stopped writing great songs. One of these is “Snowin’ on Raton,” the opening track to his 1987 album At My Window. It is not so much the story of a man leaving his loved ones as a series of wintry images that convey this departure’s effect: a city where the wind won’t blow, a mountain where the moon won’t rise, a solitary figure wandering toward nowhere in particular. Like “To Live Is to Fly” and “Fare Thee Well, Miss Carousel,” it also contains broad but powerful observations about the nature of life and love. “Bid the years goodbye, you cannot still them / You cannot turn the circles of the sun,” Van Zandt sings liltingly in the third verse. “You cannot count the miles until you feel them / And you cannot hold a lover that has gone.”—AC

“I’ll Be Here in the Morning”

https://youtube.com/watch?v=yXCA9_RRG-E

Van Zandt’s catalog is full of songs like “Snowin’ on Raton”: lonesome ramblers stealing away in the middle of the night, without the women they love, usually for no stated reason other than the allure of the open road. “I’ll Be Here in the Morning” at first seems like yet another entry in this category. “No prettier sight than looking back on a town you left behind,” Van Zandt muses early on. Then there’s a twist, one that scans both as an earnest expression of devotion and a wry self-deprecating joke. The songwriter acknowledges his own commitment-averse tendencies, but promises he’ll be different this time. “I’d like to lean into the wind and tell myself I’m free,” he sings, “but your softest whisper’s louder than the highway’s call to me.” The object of his affection understandably needs some reassurance, which he attempts to offer in the chorus: “Close your eyes, I’ll be here in the morning / Close your eyes, I’ll be here for awhile.” Given the way the harmony shifts unexpectedly to a doleful minor chord on that last word, we’re not sure whether to believe him.—AC

“No Place to Fall”

“No Place to Fall” is one of several Van Zandt standards that he was playing live a full five years before releasing them in studio versions (on 1978’s Flyin’ Shoes.) In the album version, the production and arrangement playfully leans into the song’s waltz time feel, with a chunky strum, full drumbeat, and scintillating backing vocals forming an ironic counterpoint to the mournful ambiguity of the lyrics. “No Place to Fall” starts as a tentative entreaty, and ends up more irresolute than it began, with the hope of lasting connection likely to remain a dream. Townes sketches the outline of the depressive experience, a particular gift of his—being “forever blue,” overwhelmed by the rush of time and cloudy days. The embryonic solo performance of “No Place to Fall” on Live at the Old Quarter is the most affecting version, backed by Townes’ loose strum and bright, tuneful vocal delivery. A slightly more rough-hewn solo rendition, from a private performance taped in 1988, is another essential document.—WCW

“Pancho and Lefty”

A story of two outlaws on the run, “Pancho and Lefty” offers what might be the purest distillation of Van Zandt’s songwriting voice, packed with the sort of drolly intimate details that could only come from a lifetime of tragicomic hardship. “Living on the road, my friend / Was gonna keep you free and clean / Now you wear your skin like iron / And Your breath’s as hard as kerosene,” he sings through a low-end drawl. One of Van Zandt’s most memorable melodies, the song later was later covered by Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard, making it to No. 1 on the Billboard country chart in 1983. Yet even with all their vocal harmonies and studio polish, the cover never could come close to the original, where the songwriter achieves the kind of road-worn, empty-bar feeling that few to this day have been able to capture, as much as they’d like to try. Never has the word “federales” sounded so unshakably essential.—RA

“Buckskin Stallion Blues”

Some singers start to lose their voices as they get older; Van Zandt somehow found even more of his. On late-period albums like At My Window and 1994’s No Deeper Blue, his instrument is noticeably weightier than it was in the ‘60s and ‘70s, with a newly robust low end filling space in the mix. He uses it to great effect on “Buckskin Stallion Blues,” digging deep into each line. “If love can be and still be lonely, where does that leave me and you?” he asks over simply strummed acoustic guitar, and doesn’t pretend to know the answer. “Buckskin Stallion Blues” is the work of a mature songwriter, one who hadn’t lost his ability to crush you with a few carefully arranged words, or his sense of humor. “‘Buckskin Stallion’ is about a girl and a horse,” he sometimes told audiences as an introduction to the song. “And I still miss the horse.”—AC