This story originally appeared in the April 1996 issue of Spin. In honor of Scott Walker’s life and death on March 25, we’re republishing it here.

Even before Lou Reed, Scott Walker hid behind dark sunglasses in the night. From 1965 to 1967, along with two other former California college students, Gary Leeds and John Maus, Walker sang and played bass with the Walker Brothers, a trio whose moody hits like “Made It Easy on Yourself,” “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine (Anymore),” and “My Ship Is Coming In” allowed them to briefly rival the Beatles in England. Even today, their melancholia is striking. “A few years ago, we used The Best of the Walker Brothers as the music before we played,” says American Music Club’s Mark Eitzel. “We always came onstage right after ‘My Ship Is Coming In.’ Because it’s, like, the saddest song in the world.”

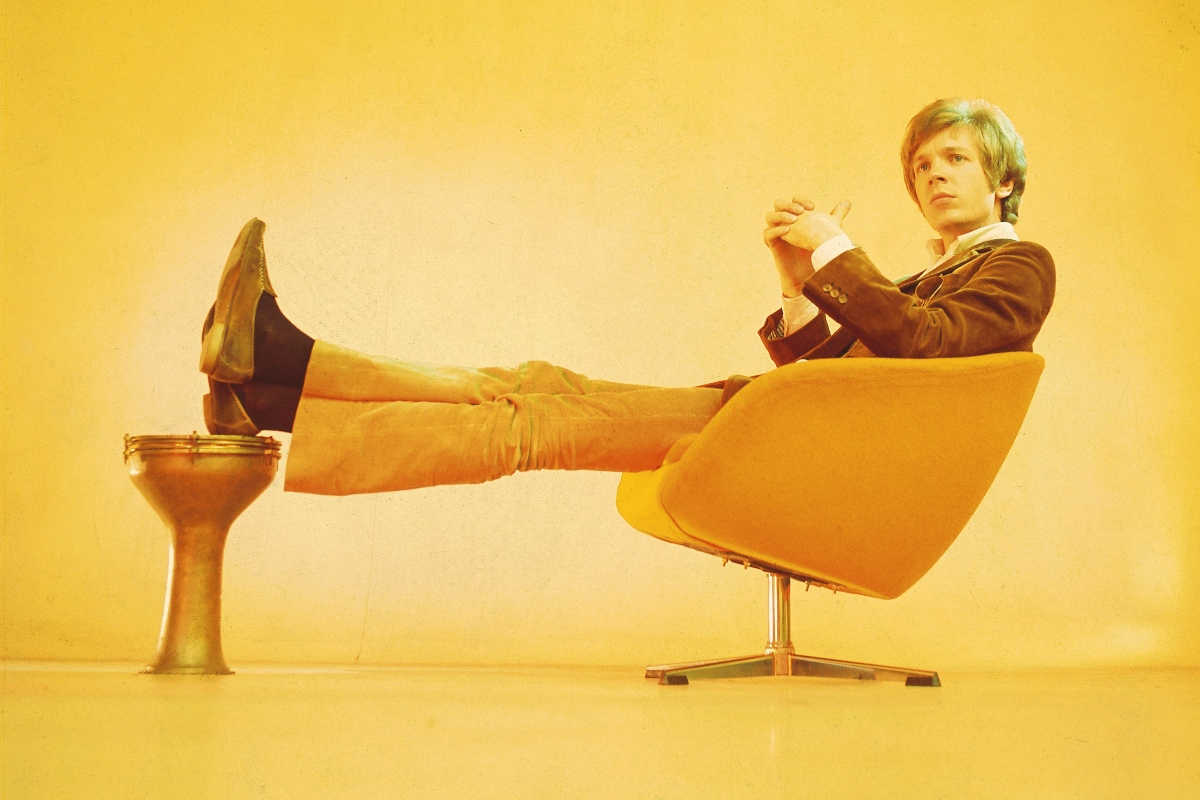

“I think the trouble is we went on too long,” says Walker, now 52, sitting in London and talking in one of the world’s coolest speaking voices, half Ricky Nelson asking Ozzie for the car keys, half Jeremy Irons making jet-fast references to Mahler. “It’s hard to remember specifics, because we recorded so many things with the same formula, basically.”

After the Walker Brothers disbanded, his solo albums between 1967 and 1979—Scott, Scott 2, 3, and 4, plus Til The Band Comes In, a compilation of which Razor & Tie will release this summer under the title We Know, Don’t We?: The Scott Walker Collection—shucked off some of the Spectoresque sound while still clinging to large melodies. These records have the theatrical finesse of Roy Orbison but the almost perverse self-dedication of Alex Chilton. Inspired by the showbiz cerebralisms of Jacques Brel, an album of whose songs he covered, Walker emerged as an artist fed by the high ambition of ’60s rock, but stylistically still soulfully, intelligently, and passionately in the classic American pop vein of Sinatra and Bennett.

“I’m particularly drawn to the thick orchestration of Scott 3,” says Eric Matthews, whose pal Bob Fray of Sebadoh first introduced Walker to him several years ago. “Nelson Riddle, Gordon Jenkins—this is the level of string writing and orchestral treatments that we’re getting on this Scott Walker record.”

Then things soured with Scott 4, a commercial bomb, leading to Walker’s flight from the business. His nemesis, as it turned out, was the commercial expectation raised by his awesome voice, a technically spot-on, haunting crooning-instrument like none other. “This has been the bane of my life,” he explains, “because I’ve always had this two-edged-sword thing going on. Everybody’s always imagined over here that at a certain stage I could have been, I don’t know, George Michael or somebody. And of course if I’d written anything in that vein, they’d have liked that as well. But I couldn’t do that.”

His staunch pursuit of the unexpected continued—on Scott Walker time. In 1983, eight years after two hit Walker Brothers-reunion albums—with surreal countryesque touches of their own—had briefly returned him to the British charts, he made Climate of Hunter, an album that previewed, with only a big more pop finesse, the bombed-out lieder on last year’s Tilt (Fontana UK). There he trades crooning for an almost deliberately ugly, nonlinear vocal approach—Walker himself, invoking the 1960s operatic tenor, calls it “strangled Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau.”

These albums spring from an extraordinarily, hyperbolically, specific pop aesthetic. “The last two albums I’ve done were totally different,” Walker says. “I was relying on the lyric to tell me what to do. For years now, you just make the track, and to hell with the lyric. I simply reversed the process. The music is broken-up, collaged, fragmented traces of everything that is left of my style. Once you solidify any one thing—even in a consecutive beat driving through—you’re in trouble.”

Walker may attempt another album at the end of 1996, after perhaps a few live shows in England—they’d be his first in two decades—and a London exhibition of the drawings and paintings he’s worked on while away from music. What the album will sound like is impossible to predict. He’ll see what the “inner quality” he listens for dictates. “It could be that next time I’ll make a total groove record,” he says,making promises only to avoid “phony soul.” He’s not a contrarian or a softie or a kook. He’s just a smart, gifted guy, hardly hostile to the styles and fashions of music around him yet unwilling to be enslaved by them. He just couldn’t do that.