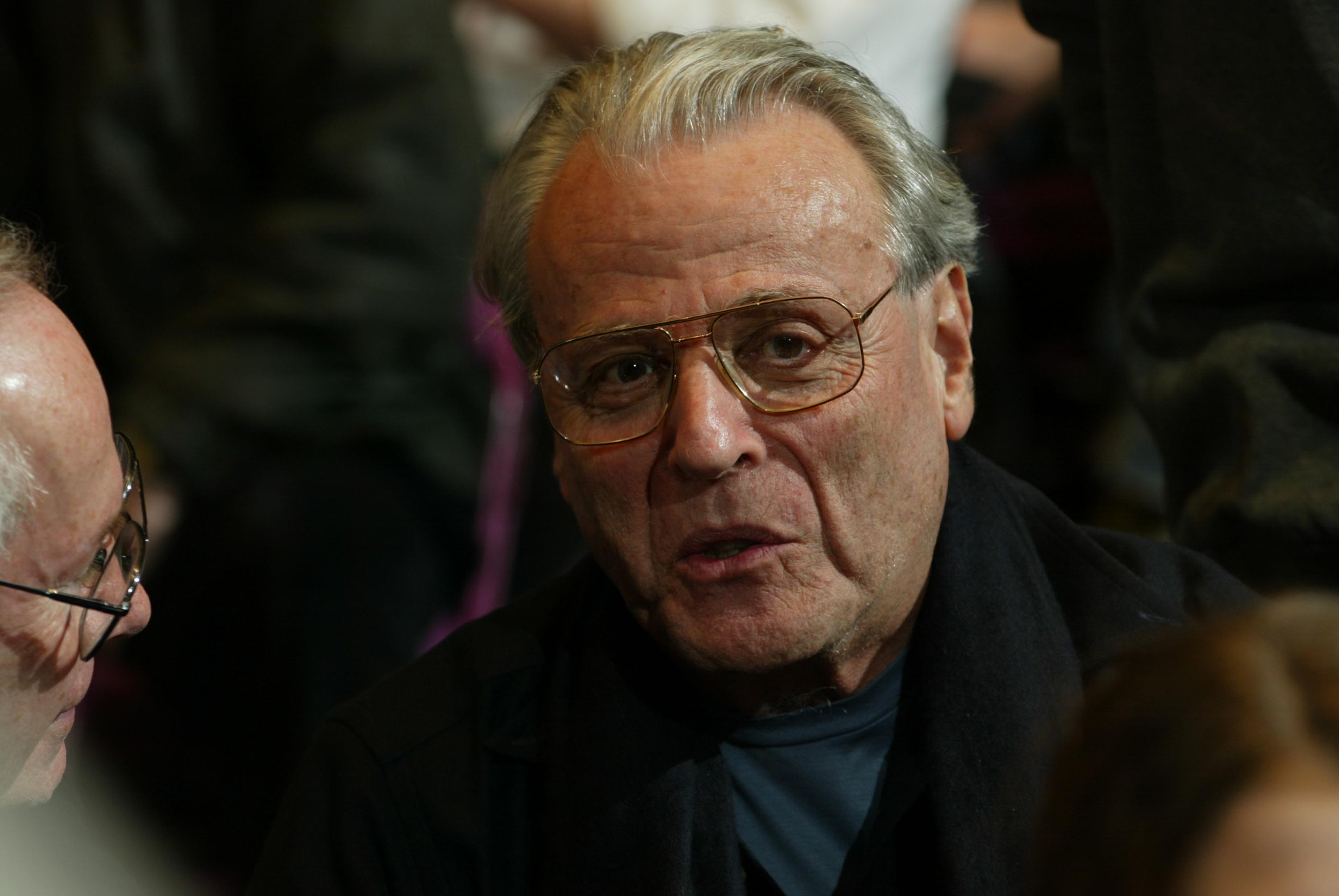

William Goldman, the straight-shooting maverick who won Academy Awards for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men and then authored the book on screenwriting, has died. He was 87.

Goldman, who also wrote the novels and then the screenplays for Marathon Man (1976), Magic(1978) and the much-loved The Princess Bride (1987), died Friday in his home in Manhattan, The Washington Post reported.

The cause of death was complications from colon cancer and pneumonia, his daughter Jenny Goldman told the newspaper.

A longtime resident of New York who hated to step foot in Hollywood, Goldman also gained fame for his nonfiction books about the business. In Adventures in the Screen Trade, published in 1982, he’s credited with coming up with the final dictum on Hollywood genius: “Nobody knows anything.”

“Nobody knows anything,” he wrote. “Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.”

In a review of Adventures in the Screen Trade, filmmaker John Sayles wrote that the book’s “final section is the best discussion I’ve read of the pitfalls of tackling a screenplay.”

Goldman then penned another perceptive critique of show business, 1990’s Hype and Glory, which documented his experiences while serving in 1988 on juries at the Cannes Film Festival and the Miss America pageant. And in 2000, he published Which Lie Did I Tell? a frank and juicy depiction of showbiz and artistic practices.

In his books about Hollywood, Goldman noted that he frequently fought battles with directors — “writer killers,” he called them — who had no vision of what they wanted, so they demanded constant rewrites.

Nobody Knows Anything (Except William Goldman) was the title of a documentary about him.

After doing research on the famed Hole in the Wall Gang of the 1880s for roughly eight years, Goldman churned out a screenplay for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). After what he described as “an insane auction,” Richard Zanuck at 20th Century Fox bought his unconventional Western — his first original screenplay — for $400,000.

“It was shitload of money then … really a freakish amount,” Goldman recalled in a 2010 Writers Guild Foundation interview with Michael Winship. “It got in all the papers, because nobody at this time knew anything about screenwriters; all they knew is that actors made up all the lines and directors did the visuals.

“The idea that this obscene amount of money going to this asshole who lives in New York who wrote a Western drove [others in Hollywood] nuts. It was the most vicious stuff. And when the movie opened, the reviews were pissy, because they hated me.”

The public, though, adored Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, making it highest-grossing film of 1969 (it raked in more than $102 million, or about $665 million in today’s dollars).

Goldman had worked closely with director George Roy Hill before and during production, and the film, which starred Paul Newman and Robert Redford as the charming outlaws, also collected four Oscars.

Adapting the complicated Carl Bernstein-Bob Woodward book All the President’s Men was a terrible experience, he said. Redford claimed in 2011 that he and director Alan J. Pakula essentially rewrote Goldman’s script for the 1976 four-time Oscar winner after Goldman abandoned the film to work on Marathon Man.”

I had all kinds of cute, humble things to say, and they’re all gone,” he said in his Oscar acceptance speech.

Goldman once asked his then-young daughters what they wanted him to write about next, and one said “princesses” and the other said “brides.” And he said he got the idea for Marathon Man when he was walking through Manhattan’s Jewelry District, then populated by Jewish emigrants, and had the notion, “What if the world’s most wanted Nazi was walking on this street?”

Goldman’s impressive body of work also included The Stepford Wives (1975), A Bridge Too Far(1977), Chaplin (1992), Maverick (1994), The Ghost and the Darkness (1996), The Chamber (1996) and Absolute Power (1997).

“You can only write what you give a shit about,” he said. “If, for example, you don’t like special effects movies, don’t try to write one because it will suck.”

He regretted turning down at least three opportunities during his career: to work on The Godfather, The Graduate and Superman (he loved comic books).

Goldman was born on Aug. 12, 1931, in Highland Park, Ill. His father, an alcoholic who worked in the clothing business, killed himself when Goldman was 15, and it was his son who found the body. He described his childhood as miserable.

He attended Oberlin College (future legendary Broadway composer John Kander was a classmate), where he said no one liked his writing, and then he got a poor grade in a writing class at Northwestern. He was rejected time and again when he submitted stories to The New Yorker; he said one time he received a rejection letter in the mail the same day he had sent in something.

After two years in the Army doing menial tasks, Goldman came to New York and earned his masters at Columbia, with his thesis titled The Comedy of Manners in America. At the time, he was living in an apartment with his brother James and Kander, who was then giving voice lessons for a living. (Later, the three combined for the Broadway musical comedy A Family Affair, starring Shelley Berman.)

In a panic over what he was going to do with his life, Goldman started writing a novel and realized he was on page 50 (he had never gotten beyond page 20 before). The Temple of Gold was finished in less than three weeks and then published in 1957. The title was a tribute to his favorite film, 1939’s Gunga Din.

Goldman had five novels published before age 33, including 1964’s No Way to Treat a Lady, based on the premise, “What if there were two Boston Stranglers and one was jealous of the other?” It was written under the pseudonym Harry Longbaugh, the real name of the Sundance Kid, played by Redford in the film.

When actor-producer Cliff Robertson approached him to write a screenplay, Goldman had no idea what to do. He headed to a Times Square bookstore late one night to find out how to put one together.

Robertson signed Goldman to do some rewriting on Masquerade (1965). No Way to Treat a Ladywound up being adapted by John Gay for a 1968 thriller starring George Segal.

Goldman then won accolades for adapting Ross Macdonald’s novel for Harper (1966), the Raymond Chandler-esque detective yarn starring Newman.

Following the success of Butch Cassidy, Goldman teamed with Redford on projects including The Hot Rock (1972), The Great Waldo Pepper (1975) — also directed by Hill — and All the President’s Men.

Goldman noted in a 1984 interview that he had written 10 novels in a 20-year span. “Well, that’s one every two years, and I have got to do something in between. So what I found to do in between is write movies. I don’t have very much respect for anyone who is just a screenwriter, in terms of their writing. Writing a poem is hard. Writing a sonnet is hard. But writing a screenplay … it’s not that it’s easy, it’s different. It, as I’ve said, is basically a skill.”

Goldman never wanted to direct, which he said set him apart from other screenwriters, and his skills as a script doctor were legendary. He was given credit for saving Good Will Hunting (1997) but disputed that, noting that he only made a suggestion to Matt Damon and Ben Affleck about cutting an unnecessary FBI subplot. He received “thanks” in the credits.

Goldman had a wisdom and sense of story that often rankled story analysts and confused producers and directors. He realized the power of scenes that didn’t necessarily advance the plot; those often ended up being audiences’ favorites.

He dubbed such scenes as being akin to the “Ol’ Man River” scene in Show Boat. “It’s a turn,” he said. ” ‘Ol’ Man River’ doesn’t advance the story. It just makes that trip more pleasant.”

His screenplays for the films Heat (1986) and Wild Card (2015) were based on his 1985 novel. He also dissected the jockeying and political chicanery of Broadway in his 2004 book The Season.

“Screenwriters are the basis, I think, of everything,” he said in the WGA Foundation interview. “If you have a shitty script, even if you have Bergman or Fellini or David Lean, it’s not going to work as a movie. It isn’t.”

Duane Byrge contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared in The Hollywood Reporter.