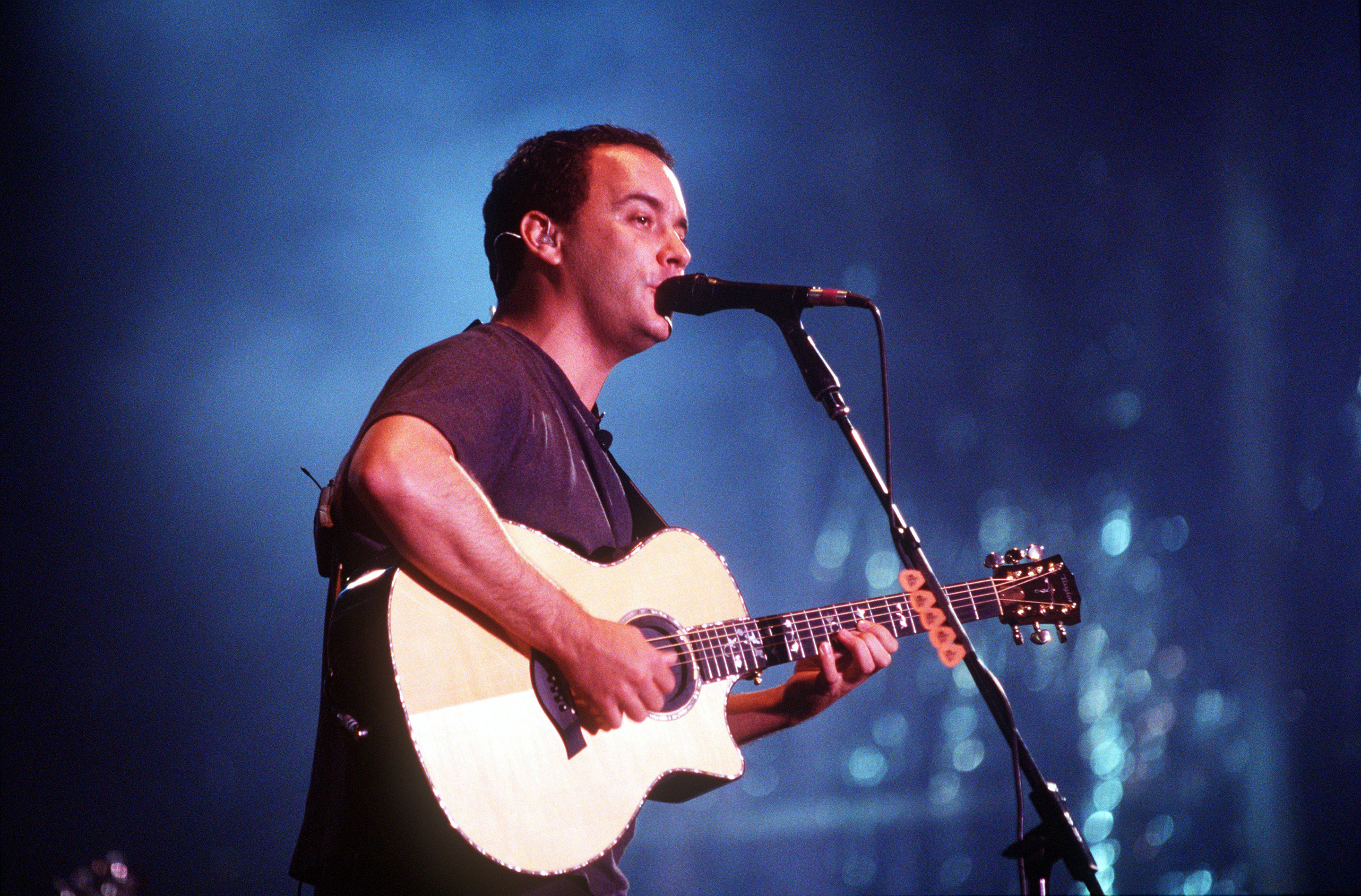

Here in downtown Atlanta’s Tabernacle, former church and deconsecrated House of Blues, a sea of snugly fitting baseball hats bob in giddy anticipation. Young Caucasians in Phish tees and polo jerseys bound about on the club’s main floor, high-fiving one another, roaring with pre-jam excitement. Some sport chin hair. Others have gone so far as to turn their caps backward. The Gap-clad, khaki-wearing Dave Matthews army is fixing to get jiggy.

Many of these lucky 1,500 had camped outside the venue, Hi-Liters and college textbooks in hand, for 30 hours to score tickets to tonight’s intimate concert filming for MTV’s Live From the 10 Spot. Bill Clinton once said that he wanted his race- and gender-mixed cabinet “to look like America.” And while the Dave Matthews Band themselves beg similar soundbites, this diehard crowd looks more like Rush Week at the the University of Kansas.

Suddenly, a cameraman appears for some crowd shots. The throng surges and threatens to spill over the barrier. A chilling refrain is taken up. “Dave is God…Dave is God…Dave is God!…”

Inside the bowels of the theater, God, dressed in a blue Armani Exchange shirt, black pants, and sensible shoes, paces a corridor. He stops and sighs.

“Think I’m going to have a movement soon,” he says, scratching his chin. “Better go and find a quiet place. Don’t want to go out there burdened.”

Matthews turns on his heel and, bursting into a broad, operatic nonsense aria, walks off down the hall. He returns momentarily in a new character: a sour, pissed-off, Hollywood executive type with a voice like Simpsons bartender Moe. “Jesus Christ,” he says, frowning. “This is just fucking crap. It’s all just fucking crap.” He walks over to a doorway where Steve Lillywhite, the band’s longtime producer, stands with a smiling young woman from MTV. Lillywhite tells him she’s waiting for a set list.

“Oh,” Matthews says brightly, now in a fey British accent. “Well, wait you will.” And goes trotting off, returning in a few moments to oblige.

In person, Matthews is absolutely unlike his distant, rather stonefaced video presence. He seems younger, with an easy charisma and the rakish, dissipated-altar-boy looks of Robert Downey, Jr. “When I was thinner, this beautiful woman who I once worked with said, ‘You have lanky charm,'” he recalls in a light Southern drawl. “‘Lanky charm like Tom Hanks.’ So I was excited. Since then, people stopped saying Tom Hanks and they started saying Forrest Gump.” A fan of Nine Inch Nails and casual friend of Marilyn Manson, the 31-year-old has an infectious, anarchic sense of humor and quirky charm that’s strangely absent from his musical persona.

He goes into the dressing room and stands before a full-length mirror. He pulls out a tissue and blows a perfect F-sharp. He slumps in the fluorescent light and stares into the mirror, assuming the stance of a pale, congested study-hall dweeb. “Hmmm. Compelling, isn’t it?” he says. He fiddles with his hair, going into the voice of a mincing stylist. “Maybe I’ll part my hair to the side. Do a sort of little boy thing.”

Bassist Stefan Lessard walks in.

“How do I look?” Matthews asks him. “Should I take my wallet out?”

“Yeah, lose the wallet.”

And with that, the singer for the biggest rock band in the country takes the stage.

***

While you weren’t looking, the Dave Matthews Band have gone from being just another H.O.R.D.E.-tourin’, Hacky Sackin’ road act to a bona fide rock phenomenon. The band’s third studio album, Before These Crowded Streets, shipped 1.7 million copies, bringing to an end the Titanic soundtrack’s 15-week reign of terror atop the charts. The band sold out the 78,000-capacity Giants Stadium in 90 minutes, entering Spice Girls territory. And, in an effective riposte to the critics who dismissed Matthews as a boomer-soothing hack, this concert even featured critic-darling Beck—as an opener. Partly through attrition and partly by changing mass tastes, Dave Matthews is theatening to replace the likes of Kurt Cobain and Eddie Vedder as rock’s alpha male, a prospect that disquiets him as much as anyone. “Eddie Vedder,” he says. “He’s real sharp-looking, isn’t he? Him, Kurt Cobain, those guys are serious. I feel more like…Elmer Fudd.”

His detractors would call that generous. To many, the Matthews Band represent nothing so much as the bland face of Clinton-era diversity. Onstage and on MTV, guitarist/singer Matthews, violinist Boyd Tinsley, bassist Lessard, saxophonist LeRoi Moore, and drummer Carter Beauford seem like a blatant challenge to the homogeneity and segregation of the rock, rap, country, and R&B worlds. Yet their sonics and sentiments are more in tune with the music of a generation ago. They have the most unconventional instrumental lineup in rock music—sax and violin? no electric guitars?—yet they play perky, deracinated pop songs that cheer the Heartland and make critics cry Hootie.

But all this may be changing, thanks largely to the group’s new Before These Crowded Streets. Unlike their two previous studio records, Under the Table and Dreaming and Crash —both of which presented studio versions of songs from their frat-honed live set—the band’s newest album was conceived and performed as a distinct new work. Rather than a gnomic little country-funk jamboree, the record’s first single is the slow and menacing “Don’t Drink the Water,” an elegiac indictment of good old American-style genocide, with backing vocals by Alanis Morissette. Other songs, such as the stormy, Kronos Quartet-driven “The Stone” and the rhapsodic “Pig,” strive for the kind of weighty, shimmering grandeur that can be heard on Peter Gabriel’s So, U2’s The Joshua Tree, and other opuses of the genre once called modern rock.

“The whole band seems to be growing up, feeling more confident about taking risks,” says Lillywhite, who has also produced records by U2 and Phish. “We tried a bit to be like Radiohead, who we love to death, and the way that they try and change things every album. Or the Beatles. Great bands change things every time.”

Part of this change can be credited to the slowly building influence of the various band members, who have a nearly 20-year range in ages among them. Beauford is a merry, smiling presence who used to play in the house band for a BET jazz program and, at 41, is old enough to remember segregated theaters. Lessard, a skinny, green-haired, 24-year-old skate punk, grew up in an ashram and is into DJ Shadow and the Propellerheads. Their rapport as a rhythm section is obvious, but it’s their differences that have helped propel the band to rock’s demographic center.

“A few years ago I was all into Pearl Jam, Smashing Pumpkins, Nirvana,” Lessard says. “And everyone in the band hated it. Nowadays it seems like everyone’s more open than they were before, and I’ve been turning them on to, like, A Tribe Called Quest and Busta Rhymes. It’s exciting.”

Nowhere is this mishmash of influences more apparent than in Matthews’s vocal work on Crowded Streets. His singing has evolved from the faux soul-revue style of “What Would You Say” into something more dynamic and interesting. Matthews even occasionally spirals off into the sort of wordless muezzin calls that evoke both his longtime favorite, Youssou N’Dour, and his deceased friend Jeff Buckley. “David uses a lot more of his voices on this album,” says Lillywhite.

In a larger context, Matthews offers a new, if rather ’60s-evoking rock presence: a brazenly optimistic Everydude who is smart without being ironic—a fitting grown-up for the Hanson age. While this persona offers little of the fascination surrounding stars like Cobain and Vedder, Matthews’s music conveys a hopeful yearning and inclu-siveness that’s more in line with Kennedy-era optimism than just about any rock of the past decade. “We play music for anyone that will listen,” he says. “It’s not aimed at people who are mad or people who are happy. It’s aimed at people, you know?”

The band’s populism becomes even more potent when one considers what a strangely mass-market-worthy pop phenomenon it is. By sheer accident, the instrumentation and group energy of DMB have aligned to evoke the entire spectrum of middle-of-the-road music. This does not mean they sound a little like R.E.M. and a little like Pearl Jam. It means they sound a little like R.E.M., a little like Pearl Jam, a little like Garth Brooks, a little like Kenny G., a little like Babyface, and a little like the Titanic soundtrack. Which in some ways makes this band quite mundane, and in other ways makes it very, very strange.

***

“My whole life pretty much revolves around working out,” says Boyd Tinsley. He is in the locker room of a swank Atlanta gym, beginning a ritual he performs three hours a day, six days a week. In Tinsley, Matthews has the most in-shape sideman in music. Peeling off a skintight Dolce & Gabbana shirt, he reveals the broad, muscled back that starred in a JanSport knapsack ad. The six-foot-two, dreadlocked violinist doffs his underwear, impressively, and changes into shorts and a T-shirt.

The first stop in his exercise routine is the StairMaster. He mounts it and, pumping and sweating, offers thoughtful, friendly observations on life in the Dave Matthews Band for the next 30 minutes—the StairMaster set to ten.

“Dave first asked me to play on the demo version of ‘Tripping Billies,'” Tinsley remembers. “And I fell in love with the music as soon as I heard it. I was never blown away by something so quick in my life.”

No novelty, the racial makeup of the band was simply par for the course in Charlottesville, home to the University of Virginia, Jefferson’s Monticello, and numerous microbreweries. “There’s a lot of great musicians in Charlottesville and everybody plays with everybody,” says Tinsley. “The country guys play with the rock guys and the punk guys play with the jazz guys.” Studying history at U. Va., Tinsley fell into jamming with musicians at a “hippie frat-house” and discovered a vibrant and surprisingly diverse local scene. “Charlottesville is on the northern edges of the South,” he says, “and it’s sort of a liberal enclave in a pretty conservative state.”

Charlottesville’s enlightenment must have seemed anything but standard to Matthews, who, in 1989, had moved there from that less-than-liberal enclave, South Africa. Born in Johannesburg, Matthews was raised by Quaker parents who brought him up staunchly anti-apartheid. He lived from ages two to 13 in Yorktown Heights, New York, where his physicist father worked for IBM, but returned to Johannesburg after his father’s death. There, attending a strict, English-style secondary school—where he was occasionally caned—Matthews would attempt a sort of punk-rock prankster approach to resistance, carrying his black friends into segregated snack bars and saying, “See, they’re not touching the floor so they’re not really here.” The government’s regime forced his hand soon after high school; when faced with mandatory military conscription, Matthews renounced his South African citizenship and left for the States.

When he relocated to Charlottesville, where his father had once taught, Matthews became a longhaired fixture in campus world-music classes and an avid fan of local jazz. He got to know Moore and Beauford by serving them drinks at a neighborhood boîte called Miller’s. It was only after Matthews’s early mentor Ross Hoffman persuaded the closet songwriter to make a demo tape that he screwed up the nerve to ask these local super-pros to play his music.

“The tape Dave gave me grabbed me immediately,” says Beauford. “It wasn’t jazz, it wasn’t rock, it wasn’t folk—it was something different.” Locals agreed, and soon the group’s party-ready mix of countrified bonhomie, jazzy acumen, and butt-wiggling grooves had people lining up around the block outside clubs such as the Eastern Standard and Trax, where that venue’s manager, Coran Capshaw, was so struck by the band that he signed on as manager.

Capshaw, who has logged some 400 Grateful Dead shows, proposed a Dead-like approach to bringing the band to the world. “We played anywhere there were paying gigs,” says Capshaw, “private parties, fraternities, sororities. We also allowed kids to tape our shows. We’d come into Athens, Georgia, on a Monday night, and we’d have 800 people because we’d built up this momentum.”

This is a classically ’60s brand of rock community-building. Much like the neo-hippie acolytes of Phish, DMB’s tape-trading fans clearly worship the group’s musical expertise and savor every new riff or novel instrument they bring out on stage. “I saw Smashing Pumpkins six times and they played the same thing each time,” a young man in the taping section of a Phish show complained to me. Phish and DMB concerts provide both mass congeniality and the aura of musical quality—Woodstock for the educated consumer. A blue-chip investment that Matthews’s tie-dyed and Greek-lettered constituency recognized immediately.

Although he’s clearly quite different from them, Matthews seems at peace with his fan base. “If I went to a university, I never would have been a member of a frat and I think those frat boys probably know it,” he says. “But we’re not aiming to avoid any group of people. More and more now I look out and see someone with five nose piercings and HATE tattooed across his forehead and I’m flattered. That’s awesome.”

***

For some reason, there are few tattooed foreheads visible in our present location: a sports bar in downtown Atlanta. We’re joined by several members of the DMB operation—merchandise people, A&R folk, a lighting guy—all of whom hang together socially, more family business than rock entourage. As REO Speedwagon plays on the jukebox, Matthews begs off a darts game (“I only play darts when I’m on mushrooms”) and settles at the bar for some hotwings and numerous pints of Red Brick Ale. Right in the middle of a discourse on the ferocity of polar bears, he is interrupted.

“Hey, baby—have you seen Titanic yet?” A pretty 22-year-old redhead gazes piercingly at Matthews. Here, amid the chili cheese fries and chirping videogames, her question comes off like some kind of loyalty oath. Well-buzzed, Matthews doesn’t seem sure how to respond.

“Um, no,” he says.

“You have to,” she says, as she and her friend excitedly lean over. “I’ve seen it five times. It’s the greatest movie of all time. Not only is it the best love story and Leonardo DiCaprio’s hot as shit —”

“He is hot as shit,” Matthews says gamely. “I would fuck him in a second.”

“I’d kiss him,” says the girl. “I wouldn’t fuck him.”

“C’mon. Yes you would.”

“I don’t believe in casual sex.”

“I’m not talking casual,” Matthews says. “I’m talking serious. Very serious.” The girl and her friend fall out laughing.

While Matthews’s movie taste runs more to foreign fare like Jane Campion’s An Angel at My Table, it’s not surprising that fans expect to find him at the latest multiplex romance. It was by exploring this very terrain, in the Crash hit “Crash Into Me,” that Matthews moved from frontman of a groovy frat-rock outfit to something resembling a romantic lead. Singing his frankly sensual invitation over a slow, chiming acoustic guitar riff, he became, for countless young ladies across the country, John Cusack holding the boom box outside his beloved’s window in Say Anything. It’s this dreamboat side of Matthews—who has been with his 24-year-old budding-naturopath girlfriend Ashley for five years—that has helped him cross over while fellow H.O.R.D.E. phenoms Blues Traveler and the Spin Doctors waned.

Suddenly, right after “Bennie and the Jets” finishes, that very song, “Crash Into Me,” comes on the loudspeaker. Another young woman leans over the bar toward Matthews with a big smile. “I want to thank you,” she says, looking into his eyes. “This song saved my relationship.”

***

Matthews graciously accepts such compliments, but remains sincerely humble about his songwriting abilities. Lyrics, as he will be the first to say, have never been his strong suit, always the very last task. Many songs on old DMB records still have vestigal titles like “The Song That Jane Likes” and “#41,” the long-standing numerical designation of the song.

“I’m so embarrassed by some of my earliest songwriting that I can’t even tell you,” he says. “I mean, right now it may seem to you that I’m too much of an egomaniac to tell you how bad it is, but it’s so bad that if I actually told you, you’d wish I hadn’t.”

But on Crowded Streets, Matthews felt the pressure to come up with lyrics that did more than just complement the groove. “Just before I went back to do the vocals was the scariest part,” he says. “Because the music was so good, so chest-out. Like, ‘Don’t Drink the Water’ was angry and plodding, and none of us had played anything like that. But my lyrics were gibberish. I was singing with real emotion, but it could have been about, like, the worms in Steve Lillywhite’s stomach. So when it came to the lyrics, I was like, If I fuck up these vocals, I’m the fuckup.”

While “Don’t Drink the Water” reveals a newfound declarative power, “Pig” offers the fullest realization of the most enduring theme in Dave Matthews’s oeuvre—what he refers to as his “seize-the-day songs.” This gather-ye-rosebuds-while-ye-may trope goes back to the first album’s DMB army battle cry “Tripping Billies,” with its chorus “Eat drink and be merry / For tomorrow we’ll die.” But on “Pig” he manages something surprisingly stirring and eloquent, with buoyant dynamics and William Blake-esque lyrics like “Looking at blood…deep and sweet within / Pouring through our veins…moving wine to tears.” “The earlier records were more Lollipop Guild,” deadpans Matthews. “This record is more Oompa Loompa.”

***

How would you satirize a David Matthews song? Well into a late-night drinking party, Matthews rises to the challenge, yodeling in dorky voice: “Happy, happy, happy / Everybody’s happy / Everybody’s me and were high and we’re happy.” We’re sitting at a bar in Charlottesville, blocks away from the site of Matthews’s earliest gigs as a musician. Matthews’s mom still lives in town, as do all the band members. Their new record was even tentatively titled after anagrams for the word Charlottesville. Among the contenders: “Sell the Victrola,” “The Lilacs Revolt,” “Lovers Tacit Hell,” and “Let Locals Thrive.” “This is Charlottesville,” Matthews says, hefting a brimming glass of whiskey with satisfaction.

Getting slowly sozzled, Matthews admits mystification over some critical jabs at his music. “Our music sounded new and different to us,” he says. “Maybe we’re just a retro group that sounds like all the other old rock bands that had acoustic guitar, violin, saxophone, acoustic drums, and one electric instrument. Which, I can’t think of any offhand.”

A more cutting accusation than anachronism, however, is the enduring one of lightweight perkiness, the idea that the Dave Matthews Band offers little more than feel-good music for happy feet. In fact, Matthews has had far more experience with devastating life issues than your average grunge poet. If apartheid is a life lesson, so is the early death of a father, which Matthews experienced at age ten. Matthews never explicitly addresses this grief, either in his music or in our conversations. Yet some of the funny anecdotes he offers about his youth leave a chill.

“I used to have these really bad sort of nightmares, where I would sleepwalk and wake up insane,” he says. “My sister said my eyes would turn black. We’d think about it in the morning, and we’d all get hysterical, ’cause it was so funny. You know, this little evil boy, black-eyed, just screaming things, like, ‘I can’t find my Frisbee to save me from the Chinese mothballs!… I dropped the world on my sister!’ I was, like, 11, 12, 13—it was right after my dad died.”

Matthews’s waking adult life has had its share of nightmares as well. In 1994, his older sister Anne, to whom he dedicated Under the Table and Dreaming, died in an incident that also claimed the life of her husband. When I bring this up, Matthews turns off my tape recorder and explains the circumstance of their deaths, which he prefers to leave unpublished until her children—whom he and his sister Jane are raising—are old enough to understand, which will probably be never.

So when Matthews sings “Celebrate we will / ‘Cause life is short,” he means it. When he predicts “We’ll all be dead and gone in a few short years,” he’s probably right. And when he implores us to “Stay, stay, stay / Stay for a while,” his earnestness is affecting. Hippie platitudes like “live for today” and “be here now” may sound trite, but actually meaning them is no small feat. It’s almost as remarkable as topping the charts with a violin-driven rock band.

This, then, is the subliminal weirdness of the Dave Matthews Band. Matthews has skipped the light fandango, turned cartwheels on the floor, and sold out Giants Stadium in an hour and change. But when I ask him to name the experiences that have moved him the most, the answer is surprising.

“Just being back home with my family,” he says. “That’s when I get carried away. Just being in that environment with my mother, and sister and brother.”

It’s enough, he says, to move him to tears. “We could be eating dinner and I just can’t help myself,” he says. “I’m swept away by the security, the ordinariness.”

And as Matthews’s fans have come to appreciate, the ordinary is sometimes worth celebrating.

“The solidness,” he concludes. “The regularness. It just kills me.”