This piece was originally published in the September 1993 issue of SPIN. In light of the death of esteemed food critic and former SPIN contributor Jonathan Gold, we’re republishing it here.

Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal. —T.S. Eliot

Take time with a wounded hand / Guess I like to steal. —Stone Temple Pilots

When you first heard the Stone Temple Pilots on MTV—admit it—you probably thought it was a Pearl Jam song you’d forgotten about, unless you thought it was Kurt Cobain singing, except that the chorus sounded a little bit more like Soundgarden. If you paid a little attention at a Stone Temple Pilots show this summer, perhaps peering up from the slam pit at The Edge on a dank Orlando evening, you might have heard, for example, a sort of Perry-Farrell-ish croon working over Aerosmithsonian riffing and a powerful “When the Levee Breaks” backbeat, but in an Alice in Chains sort of way.

In the ’90s, hard rock seems less a continuum of style than it does all styles existing simultaneously, an endless stream of songs and bands and poses. Critically, it’s less a question of evaluating these bands musically—they’re all tightly rehearsed, all anticharismatic, all more or less interchangeable on MTV—than of decoding their contexts, then seeing how well they pull it off. With the possible exception of the Sex Pistols, there hasn’t been a major white rock band since the ’60s that hasn’t been accused of being of being derivative of something.

Even West Coast A&R Representative Tom Carolyn, who signed the Stone Temple Pilots to Atlantic, admits, “It is sort of a Seattle-sounding band,” though he’s immediately driven to qualify that statement: “Whether you break a window with a hammer or pound on it with a rock, it still sounds like breaking glass.”

Having toured all summer with the Butthole Surfers and fIREHOSE (they passed on the opening slot of Aerosmith’s stadium tour), the Stone Temple Pilots are indisputably America’s hottest rock’n’roll band.

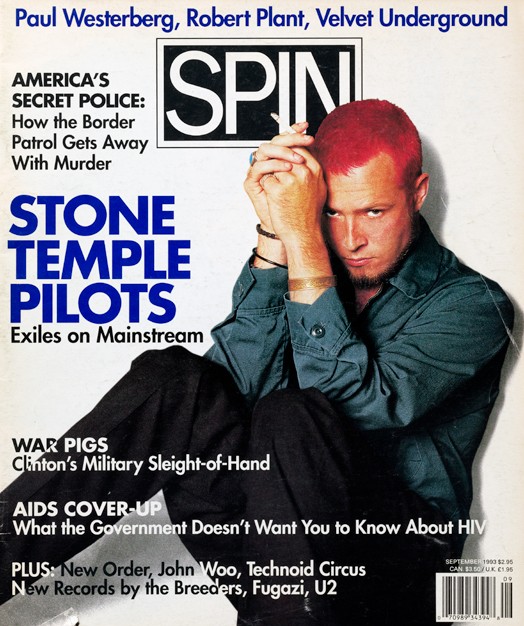

With a debut album sitting, at press time, at No. 3 on the Billboard album charts, and a second single, “Plush,” dominating radio and video airplay, they’ve ridden the backwash of the grunge wave far beyond anyone’s wildest dreams, including their own. Thanks to endless airings, their look is etched into the consciousness of every fledging Beavis and Butthead across the country. Up on the Orlando stage, singer Weiland, cherry-red crew cut gleaming in the spotlight, wheels around between choruses, arms akimbo like a hardcore kid in a 1982 slam pit. When he’s not leapfrogging across the stage, he wrings the microphone in both hands as if massaging hot oil into every crack and cranny, rather like Madonna. His black jeans ride way too low—Weiland might have the most famous plumber’s butt in America. Dean DeLeo assumes the passive hair-in-face guitar stance famous since Eric Clapton first hit a stage; his brother, Robert DeLeo, projects the usual bassist’s solidity, while drummer Eric Kretz flails and sweats. The band launches into “Sex Type Thing,” and on the perimeter of the pit, two sweaty jock dudes, more than a few beers under their belts, lunge at each other again and again, high-fives extended, bellowing like male mooses in rut.

***

At four o’clock the morning after, roaring down an interstate in the tour bus and oblivious to the pounding tropic rain, Weiland hunches over the nylon case that holds his traveling CD collection: Bad Religion, Frank Sinatra, Metallica, Miles Davis, Led Zeppelin, Pearl Jam, and Fugazi.

“I like listening to a record then saying, ‘Hey, I know what inspired that,’” Weiland says. A couple of days ago, Kretz had slapped on Jeff Beck’s Wired, which Weiland had never heard all the way through. “I was able to pick out influences on my own band I’d never noticed before.”

He idly flips through his CDs. “Sticky Fingers!” he says, examining the bulge in Mick Jagger’s pants as if he had never seen it before. “Great cock; great album.”

“Ministry’s Psalm 69: Well, only when I’m tripping, and not always then. The music takes over the whole experiences.” “Check Your Head—not as good as Paul’s Boutique, but admirable nonetheless; fIREHOSE—best band on the tour; Bowie’s Hunky Dory—’Changes’ of course, but also ‘Andy Warhol,’ which influenced our newest song, ‘Big Empty.’ Presence—the most underrated Zep album, and also my favorite.”

Weiland comes to his favorite item, a two-CD Carpenters compilation, and he breaks to into a wide grin. “The Carpenters! I love them so much that we’re going to hear it right now. And I don’t want you to think I’m listening to this because I think it’s a funny thing to do.”

It’s half past four in the morning, and “Close to You” blasts at such volume that Robert sticks his bleary head through the curtain that separates the bunks from the rest of the bus, and grimaces.

“God,” says Weiland, unaware. “Isn’t it beautiful?”

***

If you want to get technical about it, a lot of STP riffs are based around a descending pentatonic scale, rhythmically driven by a 3-3-2 division of the 4/4 bar. This is nothing new—it’s been the most popular hard-rock riff pattern at least since Ozzy’s 1981 “Crazy Train”—but almost seems so when stitched together with Weiland’s uncannily catchy baritone, punctuated by Dean DeLeo’s frankly Jimmy Page-inflected guitar. Scraps of Weiland’s melodies can swirl around in your head for hours. Perhaps more pertinent, you can sing along with a Stone Temple Pilots song, all the way through.

“Everybody draws from everybody,” says Weiland backstage, peeling a shrimp. “You take things that affected you when you were young, and you try to put them into your own version. In the ‘60s, people were reworking the blues; now, people are feeding off what they grew up with, things like fIREHOSE, Led Zeppelin, and the Beatles. It’s the food chain.”

He dunks the shrimp in spicy sauce, and pops it into its mouth. “Like with ‘Sex Type Thing,’ Dean was out in the front yard of his house in San Diego, washing his car or something, and he was, like listening to some old Zeppelin song—”

“’In the Light,’” Dean interrupts, suddenly appearing over Weiland’s shoulder. “’Duh bug ngaow, buh-neh-neh-nah neh-neh-nao-neh,’ except because the music was inside and I was outside, it sounded different. You know how you can hear music sometimes, in a different way? I heard it ‘buh-neh-buh-neh-buh-neh,’ which is like the riff idea to ‘Sex Type Thing,’ and I ran in and hit it out on the classical guitar.”

“The first time he played it for me over the phone,” Weiland says, “it reminded me of an old-style Sonic Youth-ish kind of riff. And when he told me how he got the thing, I was tweaked. Hey, I write songs that way too.”

Eighteen months ago, back when his first name was still Scott, Weiland was a failed L.A. musician like all failed L.A. musicians, bouncing from day job to day job, living in a tiny apartment with his girlfriend, plunking out cowboy chords on a cheap guitar. Stone Temple Pilots, at that time named Mighty Joe Young after a 1949 special-effects movie about an ape, gigged around at squalid artists’ hangouts, sometimes first-billed but usually not. They were never what you’d call a draw, and they were occasionally paid in beer.

It is no minor industry in Los Angeles, pretending to nurture bands toward record contracts, and there are dozens of pay-to-play nightclubs, hundreds of middlemen, scores of magazines, schools, and self-help groups dedicated to separating the aspiring musician from his dough. Look at the club listings in the alternative rags—there are more than one hundred bands on an average night playing at nearly 50 clubs, not counting major concerts at the Greek Theater, reggae cruises, gigs in suburban counties, or venues that are too underground to ever see their names in print. The number of active L.A. bands has been estimated to approach 10,000. It is safe to say that each of these 10,000 is at least half-heartedly looking for a deal.

Mighty Joe Young’s then newly acquired guitarist, Dean DeLeo, lived in San Diego, and Mighty Joe Young played down there often enough to be considered a San Diego band. San Diego was away from, as Weiland says, the tag-team wrestling for a record deal, the minimum-wage jobs on Melrose, and the pay-to-play shows on the Strip. It was a pretty easy to get a gig in San Diego, and pretty easy to build a small following.

“Music is a funny thing in Los Angeles,” says A&R rep Carolyn, “because people in the business are all so jaded. When you see a band’s name on a marquee a hundred times, you assume there’s got to be something wrong with them that everybody in town has already seen them and passed them over as damaged goods. When a band starts to happen, there’s a buzz, and everybody knows it—everybody spends too much time looking over their shoulders at everybody else. But there was no buzz, and I’d never seen the band until the night I saw them at the [now-defunct East Hollywood dive] Shamrock, and I instantly fell in love. I thank the gods of music for what happened to this band.”

At a time when the best young bands are expected to spend long apprenticeships on indie labels, supporting themselves by selling T-shirts at gigs and tooling around the country months at a time in old Tradesman vans, Stone Temple Pilots got signed, changed their name, recorded the album Core, became MTV darlings, and went platinum in less than a year. Success happened so quickly that the band itself was stunned.

“I’m just an average guy in an unaverage situation, with average friends whom I’ve known for a long, long time.” Dean, leaning against the bar of a fragrant Alabama tavern, clutches the neck of a Heineken as if it were life itself. “I couldn’t have asked for more than to be able to play my guitar, and be able to play my guitar in this particular band. But it seems like the people around me have changed. They bring cameras along when they come over, people who I’ve known for eight years, and they take my picture. Musicians from other bands we know are on a jealousy trip right now, which freaks me out, and—contrary to what everybody might believe—this band is still broker than hell, especially me. I left a very high-paying job as a contractor to do this gig, and my house is about to be taken back by the bank any day.”

Back on the bus, no longer a failed musician, Weiland feels compelled to defend himself. “Most of the bands I listen to are either on or have been on independent labels, but we decided music was music, and that a label’s only as good as the music it puts out. People get real cynical about a band that’s supposedly alternative-underground being on a major, but it’s all right as long as you have the ability to not compromise what you’re about.” From the stereo, Nat “King” Cole croons “I wish I were soooomebody else.”

Onstage in Orange County in the middle of June, in front 15,000 people at an 11-band concert for the environmental group Heal the Bay, Weiland stared out into the audience and, freaked out, stammered: “You’re all white, all good-looking, and it looks like you’ve got a lot of money.” The crowd began to cheer, and Weiland cut them short.

“No, no,” he said. “I’m not sure that’s a good thing.” The band began to play, and Weiland sang, and the crowd rocked out, but there was a strange flavor to the show.

“You know,” he said fiddling with a set of Nintendo controls, “I grew up in Orange Country, in Huntington Beach. I never did fit in. And a lot of those same kids sitting there, pumping their arms in the air, are the same kids that would’ve beaten me up seven years ago, the same kids that wouldn’t have let me into their parties. If the alternative world is only made up of white, upper-middle-class, good-looking people, what kind of world is that? I’m trying to understand it more.”

Stone Temple Pilots raised industry eyebrows when they turned down the Aerosmith slot—a spot last occupied by Guns N’ Roses—to go out on a smaller, more intimate tour with the Butthole Surfers and Weiland’s heroes, fIREHOSE. They headlined a Rock for Choice benefit concert in Los Angeles, and they donated the proceeds of another to the Bohemian Women’s Political Alliance. They insisted over their label’s objections, that the first single released off Core be “Sex Type Thing,” which is sung from the not exactly commercial point-of-view of a date rapist.

Weiland winces when the subject of “Sex Type Thing” is broached. “It’s not a political song, exactly, though the idea behind it is something that people should look at. But I don’t want to be thought of as a poster boy for the feminist movement or anything.”

It is suggested that he could do worse.

“I respect feminism,” he says, “and I guess I’ve kind of become that poster boy, but that doesn’t mean that’s all I am. That kind of objectification can ruin even sex.”

***

In a forgotten corner of Birmingham, Alabama, downhill from a stretch of ramshackle biker pads and a couple of miles behind the gleaming office towers of downtown, you’ll find a roadhouse called the Nick, all neon beer signs and video games and posters advertising the Reverend Horton Heat, with pool table in the back and a long, battered room that fairly reeks of rock’n’roll. Itchy Wigs, a groovy interracial fusion band which sounds something like the Crusaders circa 1973, has finished its set, and is taking its pay in beer. The Nick is the kind of grimy, flyer-encrusted club any musician would welcome in his or her own neighborhood.

Inside the Nick, Weiland is a happy man. The beer is cold, the company fine, and the LP by his rock band is No. 3 with a bullet. The regulars know the code here, that it’s cool to have your presence acknowledged, but also that it’s a drag to have to answer questions about your MTV Buzz clips all night long; they know you want to hear about the best barbecue restaurant in town; they know that you’d probably be pleased to have your picture right there with Jane’s Addiction, up on the back-bar wall.

Over the last hour or so, Weiland has been telling anybody who will listen that the Stone Temple Pilots might play the Nick tomorrow night instead of the sterile municipal arena into which his band is booked with fIREHOSE and Butthole Surfers. Weiland’s road manager, a badly shaven Englishman named Patrick, has been rolling his eyes and mouthing: “Noooo.” The Nick’s proprietor, Pam, is pretty amused.

Weiland doesn’t care. He’s got new, receptive friends and a fresh Jägermeister in his hands, and the time on the bar clock rolls from one to two to three. The roadies have gone on to the topless bars, Patrick to his hotel room. The sound system grows quiet. Dean is outside talking to friends. Suddenly alone, Weiland walks slowly toward the door, and then, when he’s sure nobody’s looking, hops on to the Nick’s low stage, unable to resist its pull.

Gazing out from the stage into the empty club, he snakes out an arm and grabs the closest mic stand, enjoying the feeling of the cool metal against his palm, enjoying its heft. He lunges forward into the crouched position of all lead singers everywhere, straightens with explosive force, and spins around as if he were performing again in front of 20,000 sweaty, straining dues. Weiland may not be performing at the Nick tomorrow night, but he can always wonder.