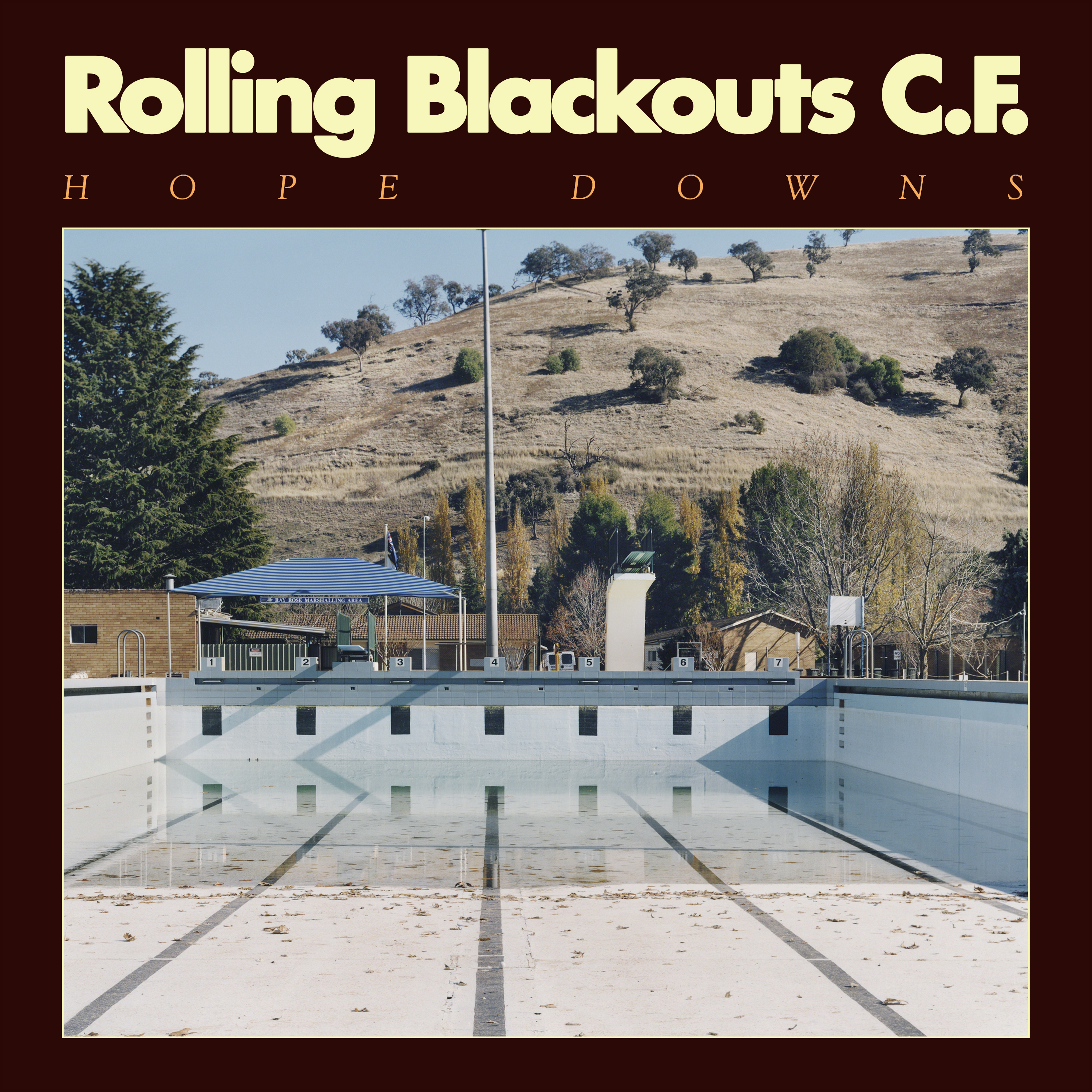

The cover of Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever’s Hope Downs shows a half empty swimming pool, with stale water and fallen leaves collected at one end: a perfect visual metaphor for their music. The Melbourne indie rock quintet’s debut album has the languor of a beachfront resort town a few weeks after the formal season has ended. One by one, the bars are closing down for the year, and the families are filtering out. But professional good-timers and vacationers still roam the streets in small packs, looking for new friends to help them while away the last of the warm weather, or at least a decent happy hour special.

“Rolling Blackouts” and “Coastal Fever” would each make a pretty solid band name on its own; it’s as if they couldn’t decide and settled on both. (You can call them Rolling Blackouts C.F. if you’re into the whole brevity thing.) Similarly, if there were any disputes about who was going to write the songs, or sing, or play guitar, they seemingly settled them by saying yes to everyone. Fran Keaney, Tom Russo, and Joe White share duties on all of the above. Over years of playing together in various bands, they have converged on a common sensibility, conveying verbose and imagistic stories via clear and simple melodies. If you’re not watching video or reading along in the liner notes, it can be difficult to know who’s singing or writing when. Given the difficulty of establishing a coherent identity around so many active contributors, that should be taken as a compliment.

Hope Downs arrives after two assured and buzzed-about EPs, which earned Rolling Blackouts C.F. favorable comparisons to jangly regional forebears like the Chills and the Go-Betweens. They distinguish themselves with what could be the most restrained, elegant triple-guitar attack in the history of rock music. Although Keaney, Russo, and White are more than capable players, Hope Downs has no “Freebird”-style extended showcases. The guitarists drift and interleave, avoiding their low strings almost entirely, while drummer Marcel Tussie and bassist Joe Russo (Tom’s brother) chug along with motorik drive. The resulting sound is like a mirage, hovering just above the rhythm section’s horizon line.

Also Read

The Best Rock Albums of 2022 (So Far)

All three writers are visually oriented, with strong senses of setting and atmosphere. As a result, Hope Downs’ crumbling cafes and “couches at other people’s houses” are just as alive as the romantics that lounge around them. On sparkling first single “Mainland,” Tom Russo is as fluent as any painter with the emotional resonance of color. The band breaks from a lope to a sprint as he takes in a seaside vista: “All I saw was burning blue / Fading into blinding white / Wade out past the rotting pier / Out to the open water / Son of a red roof city / And her the full moon’s daughter / Back on the mainland / Cool change was rolling over / Black sky was getting lower / On golden sand.” Between lines, guitars describe the shapes of buildings, the smell of saltwater, filling in details that the words leave out.

Though serene environs can be a powerful remedy for the anxieties of the real world, the cure doesn’t last forever. The lovers at the center of “Mainland” are concerned both with the beauty of the ocean and with the weary souls who frequently turn up on its shores, arriving at a country that has “shut the gate” to refugees. The wastrel protagonist of “Bellarine,” a hard-charging number from White, pines for his estranged daughter in between unsuccessful fishing trips. On the radiant “Talking Straight,” White wants to know “Where the silence comes from / Where space originates,” making the inquiry sound more like a life-and-death question than a philosophical one. But even at their most fervent, the characters of Hope Downs remain soaked in sun, able to convince themselves that one great night could be enough to set them straight again.

At about 35 minutes, Hope Downs is a brief vacation, and so are many of its songs. “Bellarine” whips to a close before we learn whether the fisherman ever reunites with his child; “Time in Common” takes the promise of “elastic time” in its lyrics seriously, zipping through several distinct scenes and still managing to feel like it’s over before it’s begun. If these stories don’t offer satisfying closure, maybe that’s the point. With a little imagination, and a willingness to chase the next cocktail no matter the cost, summer never has to end either.