Taking in the sheer sonic variety of Oneohtrix Point Never’s eighth album can be overwhelming. There are screaming synths. Human voices, natural and processed. Looping samples that stutter across the line between rhythm and pitch. Bursts of noise like you’d imagine might emanate from a tear in reality’s fabric. An obscure instrument called a daxophone, which looks and sounds like a singing saw as redesigned by H.R. Giger. A few heavy drum machines. At least one jazzy upright bass line. Amid the cacocphony, however, the harpsichord stands out as a defining element. Age Of opens with the sound of the Renaissance/Baroque-era predecessor to the modern piano, and its rich overtones remain a regular presence throughout the album.

By featuring the harpsichord so heavily in 2018, Age Of traces an invisible line between the distant past and the present. The instrument fell out of favor in the 18th century, in part because its plucked strings are incapable of producing changes in dynamics. Every time you press a key, the corresponding note comes out at the same volume, no matter how hard you press it. In the instrument’s heyday, musicians were also expected to keep a strict, unwavering tempo, favoring faithfulness to the rhythms on the page over individual expressionism—another quality ill-suited to the indulgences of the Classical and Romantic eras that followed. But steadily pulsing rhythms and unrelenting volume no longer seem so old-fashioned when considered against the backdrop of contemporary pop and electronic music. Is the insistent pace of a Bach fugue really so different from the four-on-the-floor thump of a Katy Perry song?

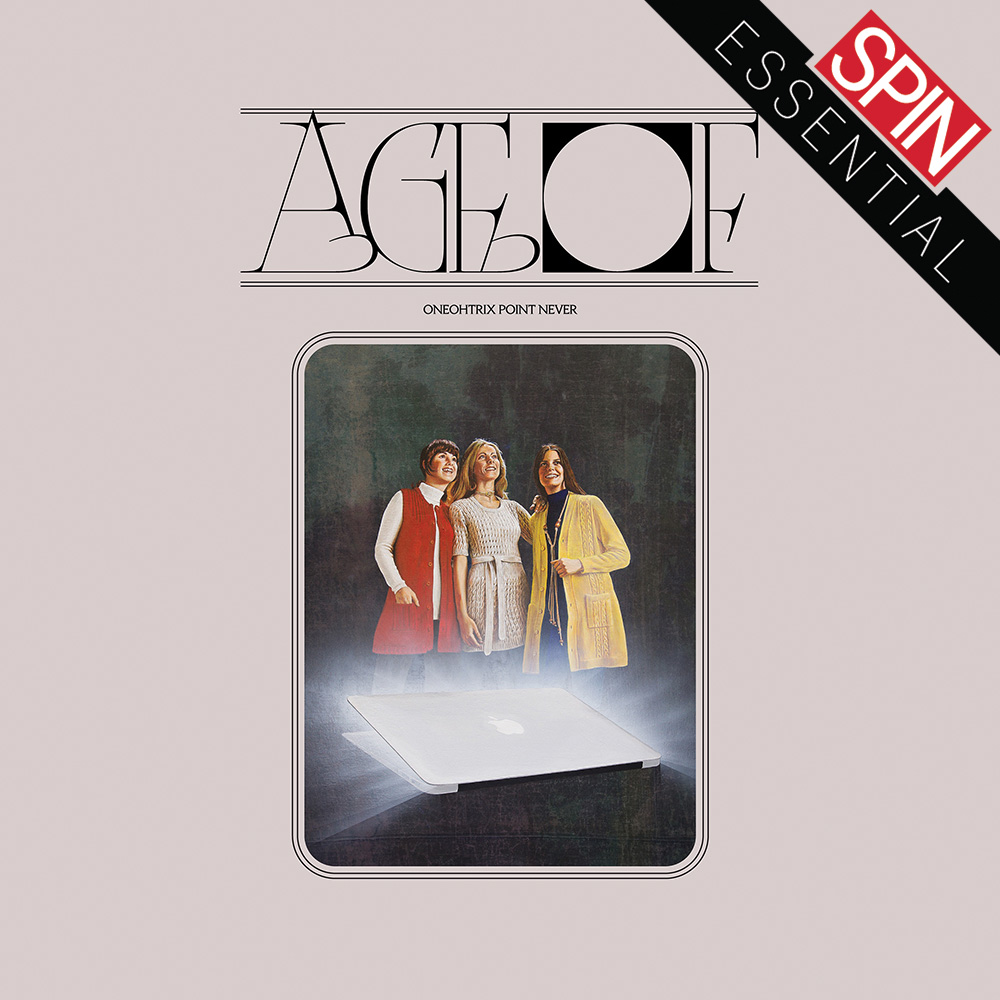

Similar questions animate Age Of, the strangest and most ambitious album yet by the electronic composer and producer born Daniel Lopatin. For all its references to the past, Age Of is a distinctly 21st-century collage, an experience roughly akin to watching old music videos on YouTube while algorithmically recommended Masonic conspiracy theories beckon from the side of the page, your phone buzzes with a push notification in your pocket, and the History Channel drones on from the TV in the other room. But rather than simply recreating this information overload, as lots of other “post-internet” art is content to do, Age Of attempts to make sense of and draw meaning from it. Lopatin is smart and funny enough to understand this as an essentially impossible task, and he frames Age Of accordingly. It is loosely based on a narrative about a future race of hyper-intelligent beings who base their understanding of our civilization on “our total sum output of everything we ever put on the internet,” as Lopatin put it in a recent interview.

Naturally, they get stuff wrong, and Age Of luxuriates in that wrongness. There are many reasons why early and contemporary music are actually quite different, but when Lopatin elides these distinctions—as when the Baroque arpeggios that close “The Station” enter a lockstep reminiscent of his synth-drone score for the 2017 thriller Good Time, for instance—it’s a musical thrill that renders questions about historical fidelity irrelevant. This passage is even more remarkable in context, coming after a warped and delectable R&B song that Lopatin apparently pitched as a demo for Usher before making it his own. “The Station” is one of several flirtations with straightforward pop structure on Age Of, which contain the album’s most obvious deviation from previous Oneohtrix Point Never records, in the form of recognizably human singing, from Lopatin himself and his collaborator Anohni. It shouldn’t all hold together, but it does. The wrongness is kind of the point: a warning that our own ideas about our ancestors’ lives and values are surely just as misguided as the future civilization’s ideas about us.

The closest antecedent for Age Of’s frenzied time-hopping is Lopatin’s 2015 album Garden of Delete, which built a caustic future sound-world from the decaying remains of EDM and macho radio rock. Age Of is not happy music, but it feels more optimistic than its bleak predecessor, albeit perversely so. “Toys 2” has a melody vaguely similar to “My Heart Will Go On,” refashioned as a new-age paean to the heavens; “Still Stuff That Doesn’t Happen” is a moment of unguarded humanity, with Lopatin and Anohni pleading in tandem, “speak to me, speak to me, speak to me.”

The closing track, “Last Known Image of a Song,” is suited to its title — all swirling static and melting harmonies, more negative space than content, like a frame still hanging long after its picture has disappeared. An upright bass enters, or a digital approximation of one, climbing to the top of its natural range and then higher, wailing out an impossible blues solo in tiny brittle chunks. Somehow, at the same time, it continues its patient timekeeping in the low end, as if this uncanny fissure never happened. The moment is lovely, haunting, and unlike anything a “real” bassist would or even could do with their instrument. By closing Age Of this way, Lopatin sends a message: if we can’t grasp the beauty in our modern chaos, we can take some comfort that others will find it down the road. But there’s no guaranteeing they won’t completely misunderstand it when they do.